OPINION

2019 Jan/29

Japan’s E-Voting for Shareholders: Current State and Implications

Jan. 29, 2019

PDF

Park, Hyejin

- Summary

- The end of the shadow voting scheme gave rise to the failures to pass resolutions at shareholder meetings due to lack of a quorum mainly for listed firms with a high proportion of individual shareholders. This serves as an impediment to the smooth running of shareholder meetings. In this situation, electronic voting (e-voting) is recently receiving intense attention as an alternative tool to normalize the operation of shareholder meetings. E-voting enables shareholders who are unable to attend the meeting in person owing to time and location constraints to exercise their voting rights, which is eventually expected to help facilitate shareholder meetings. Since Korea introduced the e-voting system in 2010, it has seen a steady rise in the number of companies entering into agreements to use e-voting service. Nevertheless, the proportion of the companies actually using e-voting still remains low. Meantime, Japan adopted the e-voting system ahead of Korea and made continued efforts to encourage the use of e-voting. Consequently, it has reaped tangible results including an increase in the percentage of institutional investors participating in e-voting and lower concentration of shareholder meetings on certain dates. Learning from Japan’s case, Korea needs to improve institutional arrangements for foreign institutional investors to take part in e-voting, for example, by revamping the method to verify the identity of shareholders, allowing shareholders to cancel or modify their votes cast electronically, and strengthening the disclosure of shareholder meeting results.

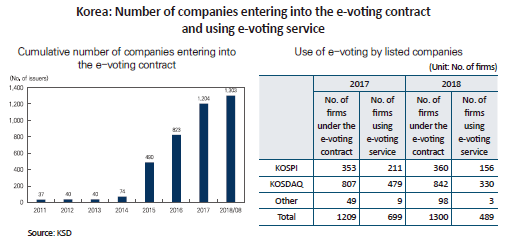

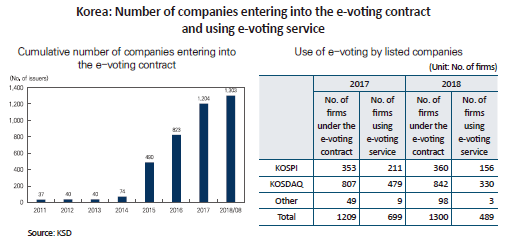

Electronic voting (e-voting) refers to voting via the internet or a mobile device by shareholders or their proxies without attending the shareholder meeting in person. While e-voting enables companies or issuers to reduce the costs of holding shareholder meetings, it allows shareholders to exercise their voting rights in a convenient manner. In doing so, e-voting would facilitate shareholder meetings, which is ultimately expected to contribute to increasing firm value and promoting shareholder interests. Korea introduced the e-voting system in 2010. Since then, the number of firms that entered into an agreement for e-voting with Korea Securities Depository (KSD) has risen continually from 490 in 2015 to 1,204 in 2017 and 1,303 in September 2018. As of now, approximately 25% of public companies have signed the e-voting service agreements with KSD.1) In practice, however, just 37.6% of those companies (i.e., 489 out of the 1,300 firms) used e-voting in 2018, which shows a sharp decline as compared to 57.8% in 2017 (699 out of the 1,209 firms). That suggests that a large proportion of the companies chose e-voting to make use of the shadow voting scheme rather than making shareholder voting more convenient.2)

In the meantime, Japan introduced its e-voting system in 2001 and continuously strived to encourage the use of electronic means in calling a shareholder meeting and voting. Starting with the adoption of the Stewardship Code in February 2014, Japan made various efforts to improve corporate governance, such as amendments to the Commercial Code aiming mainly at tightening independent director qualifications and adopting class actions in June 2014, and the introduction of the Corporate Governance Code in March 2015. Subsequently, it has reaped tangible results. For example, annual general meetings of shareholders (AGMs) become less concentrated on certain dates. The percentage of using e-voting has been on the rise mainly among top large-cap companies, and domestic and foreign institutional investors. Against this backdrop, this article explores the e-voting system up and running in Japan and draws out implications for the greater use of e-voting in Korea.

Current state of e-voting in Japan

As explained above, Japan adopted the e-voting system in 2001 as part of measures to promote the electronization of shareholder meetings, following the Commercial Code revisions. Japanese companies with 1,000 shareholders or more with voting rights must allow their shareholders to vote in writing but can decide whether to allow shareholders to vote electronically.3) There are two types of e-voting service providers in Japan. For individual investors, six trust banks including Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), which is the provider of shareholder register administration services, operate their own platforms for e-voting. For institutional investors, Investor Communications Japan (ICJ) provides an e-voting platform called, “ProxyEdge.”4)

The primary users of e-voting in Japan are institutional investors. Still, most individual investors reportedly prefer voting on paper (postal voting) to voting electronically (e-voting).5) In general, institutional investors have to mail their ballots to their trust bank at least five (5) business days before the date scheduled for a shareholder meeting from the date on which a notice to convene the meeting is given by mail. Foreign institutional investors must inform their proxy agent of their votes at least eight (8) business days from the date of the meeting, meaning shorter time to review materials on the agenda items to vote before the meeting. Thus, where e-voting is used, it would enable institutional investors to access the meeting materials on the very date on which the meeting notice is given and to exercise their voting rights through the e-voting platform until the day before the meeting. Consequently, institutional shareholders would be given more time to review the items to vote during the meeting. Another advantage of e-voting is that it allows shareholders to cancel or modify their votes several times during the voting period. Meantime, in the case of individual investors, elderly people take up a large proportion of individual shareholders and they are more familiar with postal voting (that is, marking their vote on their ballot paper and putting it in a mailbox) than e-voting (that is, voting using a desktop PC or a smartphone). Not only that, the cost in postage of returning a mail ballot is paid by the company, which is one of the reasons why there are less incentives for individual investors to use e-voting than institutional investors.

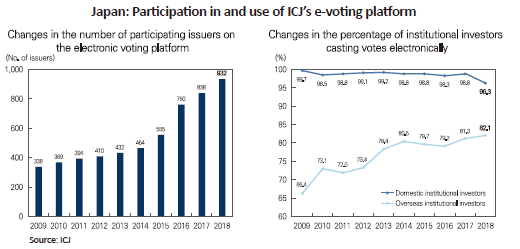

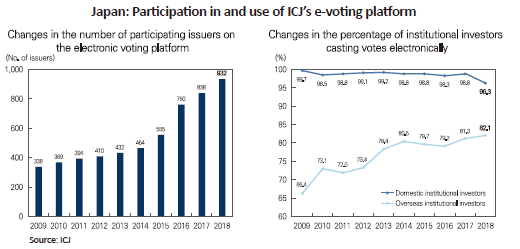

According to ICJ, 932 (26%) of 3,594 companies listed on the TSE as of July 2018 were participating issuers on the ICJ platform, representing 84.3% of TSE-listed companies in terms of market capitalization. The number of participating issuers has increased steadily over the last five years from 2014. Notably, this number soared in 2015 when the Corporate Governance Code came into effect. As regards the percentage of institutional investors casting votes by electronic means (shares voted electronically/total shares), domestic institutional shareholders casted a whopping 96.3% of their votes by electronic means in 2018 while overseas institutional shareholders casted 82.1% of their votes electronically in 2018, showing a continued increase from 66.4% in 2009.

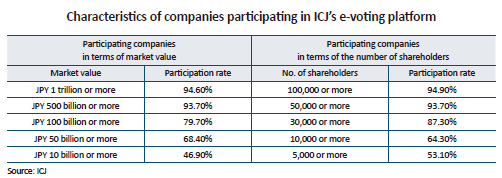

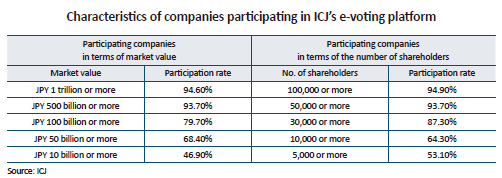

It is noteworthy that bigger companies with a larger number of shareholders tend to become the users of the e-voting platform in Japan. For companies listed on the first section of the TSE (TSE1-listed companies), less than 50% of TSE1-listed companies with a market value of JPY 10 billion or more have joined the ICJ platform whereas 94.6% of those with a market value of JPY 1 trillion or more have participated in the platform, which reveals the greater participation of higher market cap companies in the platform. In terms of the number of shareholders, approximately 50% of TSE1-listed companies with 5,000 shareholders or more were ICJ-participating issuers whereas 94.9% of those with 100,000 shareholders or more used the platform. This indicates the higher participation of companies with a larger number of shareholders in the ICJ platform.

Current state of electronic voting in Korea

Following the revision of the Commercial Act in 2009, Korea put its e-voting system in place in 2010. The amended Act allows companies to choose whether to use e-voting, which requires board approval, and also allows them to entrust e-voting operations to external e-voting platform providers. Currently, KSD is the sole provider of e-voting platform in Korea. Where a company decides to use e-voting, its shareholders can exercise their voting rights on the e-voting website not later than ten (10) days before the date of a shareholder meeting, and once they cast their votes, they cannot make changes, which is a far cry from Japan’s e-voting system.

KSD’s e-voting system received little attention after its inception in 2010. However, as advance notice was issued about the abolition of the shadow voting scheme in 2013, more and more companies began entering into an agreement for e-voting with KSD due to concerns over the lack of a quorum required for passing resolutions at a shareholder meeting.6) In 2014, the number of companies that signed the e-voting contracts with KSD was merely 74, but this number rose sharply to 490 in 2015, reaching 1,303 in September 2018. One feature of those companies is that small-cap companies rather than large-cap ones are the main adopters and users of the e-voting system in Korea, which stands in contrast to Japan. According to KSD data on the e-voting system, 20% of top 100 KOSPI-listed firms entered into the e-voting agreement, which is lower than 62% of top 50 KOSDAQ-listed firms.7)

In many cases, companies or issuers have not used e-voting service even after entering into the contract. According to KSD, the proportion of the issuers that actually leveraged e-voting fell from 57.8% in 2017 to 37.6% in 2018 following the end of the shadow voting system.8) The number of the issuers using the e-voting system dropped by 210 from that in 2017. As described earlier, this is in a sharp contrast to the steady upward trend in the number of companies signing the e-voting contracts with KSD. This phenomenon implies that a great deal of firms entered into the e-voting contract to take advantage of the shadow voting scheme, not to help their shareholders better exercise their voting rights because the FSCMA allows companies that adopt e-voting to tap into the shadow voting scheme. Further, the percentage of shareholders casting votes electronically (shares voted electronically/total issued shares) still remains low, recording 3.9% as of March 31, 2018, up more than double from 1.8% a year ago.9)

Implications

Japan’s case provides the following implications for institutional improvements to promote the use of e-voting in Korea: First, institutional arrangements should be revamped to enable foreign investors to participate in e-voting considering that overseas institutional investors are the most active users of e-voting in Japan. Although foreign investors are highly interested in the exercise of their voting rights, the concentration of AGMs on certain dates and the short amount of time to review the items on the agenda of a shareholder meeting make them difficult to participate in the meeting in person and cast their votes.10) To foreign shareholders under the time and location constraints, e-voting can be a useful tool to exercise their voting rights. Currently in Korea, however, shareholders are not able to vote electronically without using an accredited authentication certificate or digital signature certificate. Since it is impossible for foreigners to obtain digital signature certificates, they cannot use e-voting in Korea.11) Hence, it is necessary to introduce diverse authentication methods (e.g., assigning user ID and password as is the case in Japan) other than a digital signature certificate used to verify the identity of shareholders for e-voting, in order to make e-voting more accessible by foreign investors. One tentative option is to allow a foreign investor’s local standing agent to cast a vote through the e-voting platform on behalf of the investor, considering that the standing proxy can attend a shareholder meeting and vote on behalf of the investor.

Second, shareholders or their proxies should be allowed to cancel or alter their votes cast electronically, as seen in Japan. Shareholders or their proxy holders in Japan can cancel or change their votes any time not only during the e-voting period before the meeting but also upon voting at the meeting. This would work for both shareholders and issuers. Shareholders could modify their votes cast electronically when they obtain new information or the situation changes. And if there is any shareholder objecting to an agenda item and voting electronically against it, issuers could have an opportunity to persuade the dissent shareholder to switch his or her vote. In Korea, however, the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act does not allow shareholders to cancel or change their votes cast by electronic means, which excessively limits shareholders’ right to choose when using e-voting.12) Taken them together, Korea needs to revamp the relevant law and regulation to enable shareholders to change or cancel their votes cast via the e-voting platform during the e-voting period as well as upon final voting that takes place at the meeting.

Lastly, Korea should strengthen the disclosure of information on resolutions passed at a shareholder meeting from medium-and long-term perspectives, given that the inadequate disclosure of shareholder meeting results is one of the reasons for shareholder indifference to AGMs. In the case of Japan, companies are required to disclose detailed information on shareholder vote results, including the total number of votes cast, and affirmative, negative and abstention votes for each item. By contrast, most Korean companies do not disclose AGM voting results in detail due to the absence of a compulsory disclosure requirement for such information. As the widespread adoption of the Stewardship Code calls for responsible actions of shareholders with regard to the exercise of voting rights, public disclosure about the results of shareholder meetings needs to be enhanced.

1) According to KSD, 361 KOSPI-listed firms and 842 KOSDAQ-listed firms as of August 2018 entered into the e-voting contracts with KSD.

2) Shadow voting refers to the mirror voting system under which KSD, at the request of an issuer, exercises proxy voting rights on behalf of non-participating shareholders in the same proportion as the vote of other shareholders attending the meeting. It was adopted in 1991 to prevent shareholder meetings from being canceled due to lack of a quorum, and has been abolished in 2018 as a result of the revision of the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act (FSCMA) in 2013.

3) In Japan, directors or shareholders who call a shareholder meeting or a company with board of directors may adopt e-voting upon board approval (Article 298 of the Companies Act). However, companies must allow shareholders to exercise their voting rights by electronic means, provided that the notice of the shareholder meeting and reference materials have been distributed by electronic means (Article 312.2 of the Companies Act). And voting by electronic means is permitted until the day before the date of the meeting as is the case of voting in writing (Article 70 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Companies Act).

4) Established in 2014 as a 50%-50% joint venture of Broadridge, a US firm, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), ICJ provided e-voting services for nearly 6,000 shareholder meetings from 2006 to June 2018. In addition to ProxyEdge, the e-voting platform, ICJ also offers “Arrow Force”, the website that provides information on the notices of shareholder meetings from all Japanese issuers, “Proxy Solution,” the solution to support strategy formulation (e.g., voting simulation) for and operation of shareholder meetings, and “ICJ Online,” the ancillary service to notify issuers of e-voting results.

5) According to an interview of MUFC staff in charge of e-voting platform service in September 2018, only about 3% of individual clients that MUFG caters to have used e-voting over the past five years.

6) The revision of the FSCMA in 2013 was followed by a notice regarding the abolition of the shadow voting system. In 2014, however, a grace period up to 2017 was provided to companies that chose to adopt e-voting.

7) Among companies listed on the stock exchange, 49% (360) of KOSPI-listed firms and 71% (842) of KOSDAQ-listed firms adopted e-voting, which means that KOSDAQ firms are the major clients of KSD who entered into the e-voting contract.

8) 699 out of 1,209 listed companies that entered into the e-voting agreement actually utilized e-voting in 2017. Only 489 out of the 1,300 listed companies used e-voting in 2018.

9) The number of shares on which votes were cast by electronic means was 479,198,000 in 2017, and 886,452,000 in 2018. The number of the shares voted electronically per company averaged 685,000 and 1,813,000, respectively.

10) Assuming that a notice to convene a shareholder meeting is sent out to shareholders 14 days before the meeting (legal notification deadline), foreign shareholders would have only one or two days to review the agenda items considering the notice requirement for the exercise of vote in disunity - if a shareholder with at least two votes intends to exercise the votes in disunity, he or she is required to notify the company of his or her intent to do so three days prior to the meeting.

11) In accordance with Article 13.1 of the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act, where shareholders exercise their voting rights by electronic means, shareholders must use their official digital signatures as defined in the Digital Signature Act for identification and electronic voting.

12) Article 13.3 of the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act.

In the meantime, Japan introduced its e-voting system in 2001 and continuously strived to encourage the use of electronic means in calling a shareholder meeting and voting. Starting with the adoption of the Stewardship Code in February 2014, Japan made various efforts to improve corporate governance, such as amendments to the Commercial Code aiming mainly at tightening independent director qualifications and adopting class actions in June 2014, and the introduction of the Corporate Governance Code in March 2015. Subsequently, it has reaped tangible results. For example, annual general meetings of shareholders (AGMs) become less concentrated on certain dates. The percentage of using e-voting has been on the rise mainly among top large-cap companies, and domestic and foreign institutional investors. Against this backdrop, this article explores the e-voting system up and running in Japan and draws out implications for the greater use of e-voting in Korea.

Current state of e-voting in Japan

As explained above, Japan adopted the e-voting system in 2001 as part of measures to promote the electronization of shareholder meetings, following the Commercial Code revisions. Japanese companies with 1,000 shareholders or more with voting rights must allow their shareholders to vote in writing but can decide whether to allow shareholders to vote electronically.3) There are two types of e-voting service providers in Japan. For individual investors, six trust banks including Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), which is the provider of shareholder register administration services, operate their own platforms for e-voting. For institutional investors, Investor Communications Japan (ICJ) provides an e-voting platform called, “ProxyEdge.”4)

The primary users of e-voting in Japan are institutional investors. Still, most individual investors reportedly prefer voting on paper (postal voting) to voting electronically (e-voting).5) In general, institutional investors have to mail their ballots to their trust bank at least five (5) business days before the date scheduled for a shareholder meeting from the date on which a notice to convene the meeting is given by mail. Foreign institutional investors must inform their proxy agent of their votes at least eight (8) business days from the date of the meeting, meaning shorter time to review materials on the agenda items to vote before the meeting. Thus, where e-voting is used, it would enable institutional investors to access the meeting materials on the very date on which the meeting notice is given and to exercise their voting rights through the e-voting platform until the day before the meeting. Consequently, institutional shareholders would be given more time to review the items to vote during the meeting. Another advantage of e-voting is that it allows shareholders to cancel or modify their votes several times during the voting period. Meantime, in the case of individual investors, elderly people take up a large proportion of individual shareholders and they are more familiar with postal voting (that is, marking their vote on their ballot paper and putting it in a mailbox) than e-voting (that is, voting using a desktop PC or a smartphone). Not only that, the cost in postage of returning a mail ballot is paid by the company, which is one of the reasons why there are less incentives for individual investors to use e-voting than institutional investors.

It is noteworthy that bigger companies with a larger number of shareholders tend to become the users of the e-voting platform in Japan. For companies listed on the first section of the TSE (TSE1-listed companies), less than 50% of TSE1-listed companies with a market value of JPY 10 billion or more have joined the ICJ platform whereas 94.6% of those with a market value of JPY 1 trillion or more have participated in the platform, which reveals the greater participation of higher market cap companies in the platform. In terms of the number of shareholders, approximately 50% of TSE1-listed companies with 5,000 shareholders or more were ICJ-participating issuers whereas 94.9% of those with 100,000 shareholders or more used the platform. This indicates the higher participation of companies with a larger number of shareholders in the ICJ platform.

Following the revision of the Commercial Act in 2009, Korea put its e-voting system in place in 2010. The amended Act allows companies to choose whether to use e-voting, which requires board approval, and also allows them to entrust e-voting operations to external e-voting platform providers. Currently, KSD is the sole provider of e-voting platform in Korea. Where a company decides to use e-voting, its shareholders can exercise their voting rights on the e-voting website not later than ten (10) days before the date of a shareholder meeting, and once they cast their votes, they cannot make changes, which is a far cry from Japan’s e-voting system.

KSD’s e-voting system received little attention after its inception in 2010. However, as advance notice was issued about the abolition of the shadow voting scheme in 2013, more and more companies began entering into an agreement for e-voting with KSD due to concerns over the lack of a quorum required for passing resolutions at a shareholder meeting.6) In 2014, the number of companies that signed the e-voting contracts with KSD was merely 74, but this number rose sharply to 490 in 2015, reaching 1,303 in September 2018. One feature of those companies is that small-cap companies rather than large-cap ones are the main adopters and users of the e-voting system in Korea, which stands in contrast to Japan. According to KSD data on the e-voting system, 20% of top 100 KOSPI-listed firms entered into the e-voting agreement, which is lower than 62% of top 50 KOSDAQ-listed firms.7)

Implications

Japan’s case provides the following implications for institutional improvements to promote the use of e-voting in Korea: First, institutional arrangements should be revamped to enable foreign investors to participate in e-voting considering that overseas institutional investors are the most active users of e-voting in Japan. Although foreign investors are highly interested in the exercise of their voting rights, the concentration of AGMs on certain dates and the short amount of time to review the items on the agenda of a shareholder meeting make them difficult to participate in the meeting in person and cast their votes.10) To foreign shareholders under the time and location constraints, e-voting can be a useful tool to exercise their voting rights. Currently in Korea, however, shareholders are not able to vote electronically without using an accredited authentication certificate or digital signature certificate. Since it is impossible for foreigners to obtain digital signature certificates, they cannot use e-voting in Korea.11) Hence, it is necessary to introduce diverse authentication methods (e.g., assigning user ID and password as is the case in Japan) other than a digital signature certificate used to verify the identity of shareholders for e-voting, in order to make e-voting more accessible by foreign investors. One tentative option is to allow a foreign investor’s local standing agent to cast a vote through the e-voting platform on behalf of the investor, considering that the standing proxy can attend a shareholder meeting and vote on behalf of the investor.

Second, shareholders or their proxies should be allowed to cancel or alter their votes cast electronically, as seen in Japan. Shareholders or their proxy holders in Japan can cancel or change their votes any time not only during the e-voting period before the meeting but also upon voting at the meeting. This would work for both shareholders and issuers. Shareholders could modify their votes cast electronically when they obtain new information or the situation changes. And if there is any shareholder objecting to an agenda item and voting electronically against it, issuers could have an opportunity to persuade the dissent shareholder to switch his or her vote. In Korea, however, the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act does not allow shareholders to cancel or change their votes cast by electronic means, which excessively limits shareholders’ right to choose when using e-voting.12) Taken them together, Korea needs to revamp the relevant law and regulation to enable shareholders to change or cancel their votes cast via the e-voting platform during the e-voting period as well as upon final voting that takes place at the meeting.

Lastly, Korea should strengthen the disclosure of information on resolutions passed at a shareholder meeting from medium-and long-term perspectives, given that the inadequate disclosure of shareholder meeting results is one of the reasons for shareholder indifference to AGMs. In the case of Japan, companies are required to disclose detailed information on shareholder vote results, including the total number of votes cast, and affirmative, negative and abstention votes for each item. By contrast, most Korean companies do not disclose AGM voting results in detail due to the absence of a compulsory disclosure requirement for such information. As the widespread adoption of the Stewardship Code calls for responsible actions of shareholders with regard to the exercise of voting rights, public disclosure about the results of shareholder meetings needs to be enhanced.

1) According to KSD, 361 KOSPI-listed firms and 842 KOSDAQ-listed firms as of August 2018 entered into the e-voting contracts with KSD.

2) Shadow voting refers to the mirror voting system under which KSD, at the request of an issuer, exercises proxy voting rights on behalf of non-participating shareholders in the same proportion as the vote of other shareholders attending the meeting. It was adopted in 1991 to prevent shareholder meetings from being canceled due to lack of a quorum, and has been abolished in 2018 as a result of the revision of the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act (FSCMA) in 2013.

3) In Japan, directors or shareholders who call a shareholder meeting or a company with board of directors may adopt e-voting upon board approval (Article 298 of the Companies Act). However, companies must allow shareholders to exercise their voting rights by electronic means, provided that the notice of the shareholder meeting and reference materials have been distributed by electronic means (Article 312.2 of the Companies Act). And voting by electronic means is permitted until the day before the date of the meeting as is the case of voting in writing (Article 70 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Companies Act).

4) Established in 2014 as a 50%-50% joint venture of Broadridge, a US firm, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), ICJ provided e-voting services for nearly 6,000 shareholder meetings from 2006 to June 2018. In addition to ProxyEdge, the e-voting platform, ICJ also offers “Arrow Force”, the website that provides information on the notices of shareholder meetings from all Japanese issuers, “Proxy Solution,” the solution to support strategy formulation (e.g., voting simulation) for and operation of shareholder meetings, and “ICJ Online,” the ancillary service to notify issuers of e-voting results.

5) According to an interview of MUFC staff in charge of e-voting platform service in September 2018, only about 3% of individual clients that MUFG caters to have used e-voting over the past five years.

6) The revision of the FSCMA in 2013 was followed by a notice regarding the abolition of the shadow voting system. In 2014, however, a grace period up to 2017 was provided to companies that chose to adopt e-voting.

7) Among companies listed on the stock exchange, 49% (360) of KOSPI-listed firms and 71% (842) of KOSDAQ-listed firms adopted e-voting, which means that KOSDAQ firms are the major clients of KSD who entered into the e-voting contract.

8) 699 out of 1,209 listed companies that entered into the e-voting agreement actually utilized e-voting in 2017. Only 489 out of the 1,300 listed companies used e-voting in 2018.

9) The number of shares on which votes were cast by electronic means was 479,198,000 in 2017, and 886,452,000 in 2018. The number of the shares voted electronically per company averaged 685,000 and 1,813,000, respectively.

10) Assuming that a notice to convene a shareholder meeting is sent out to shareholders 14 days before the meeting (legal notification deadline), foreign shareholders would have only one or two days to review the agenda items considering the notice requirement for the exercise of vote in disunity - if a shareholder with at least two votes intends to exercise the votes in disunity, he or she is required to notify the company of his or her intent to do so three days prior to the meeting.

11) In accordance with Article 13.1 of the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act, where shareholders exercise their voting rights by electronic means, shareholders must use their official digital signatures as defined in the Digital Signature Act for identification and electronic voting.

12) Article 13.3 of the Enforcement Decree of the Commercial Act.