OPINION

2021 Feb/23

Central Bank Digital Currency: Meanings, Impacts, and Implications

Feb. 23, 2021

PDF

- Summary

- Recently, many economies around the globe have paid keen attention to central bank digital currency (CBDC), a form of central bank money that stores value digitally and settles a transaction between users via money transfer unlike physical currency. This is differentiated from cryptocurrency in that as a legal tender issued by a central bank it uses a conversion rate equivalent to that of conventional currency, and thus has no risk of value fluctuation. CBDC, if issued, is expected to improve payment convenience for individual economic entities. On the other hand, this could form a new interest rate regime and decrease bank deposits, possibly imposing wide-ranging impacts on monetary policy efficacy and financial stability. Because there are quite a few technological and legal hurdles to be overcome towards CBDC issuance, what’s needed is a cautious—rather than a hasty—approach backed by a thorough analysis on developments in other countries and the impacts.

Recent advances in IT have spurred heated discussion about digitalized currency in Korea and abroad. Ever since Bitcoin and a diverse type of cryptocurrencies emerged first in 2009, their prices have appreciated steeply enough to attract huge public attention. However, they at the same time have exposed abrupt price volatility and a limit as a medium of value transfer. In 2019, Facebook, a social-network with roughly 2.5 billion active users worldwide, unveiled its plan to issue its own digital currency Libra whose nominal value is relatively stable compared to other cryptocurrencies. This fueled expectations for immense changes in how traditional currency is viewed and used, triggering central banks around the globe including the Bank of Korea to carry out various research on issuing digital currency. In 2020, the Bank of International Settlement and six central banks in developed economies announced a plan to share their economic, technological knowledge and experience.

Against the backdrop, this article tries to offer a concise overview on the meanings and current state of CBDC, the impacts and risk factors of the adoption, and the implications of the potential issuance.

CBDC: Meanings and current state

Central banks around the globe are discussing at the moment a form of currency that digitally stores and transfers value for payment and settlement unlike conventional currency taking a physical form. Unlike other cryptocurrencies issued by private sector players, CBDC’s legal tender status makes its conversion rate equivalent to that of physical currency, which effectively eliminates the risk of value fluctuation. Also, its confidence is guaranteed because the issuer is a central bank.

CBDCs can be categorized into two types—a wholesale CBDC issued for banks and other deposit-taking financial institutions, and a retail CBDC issued for individuals and other private sector economic entities. It’s possible for individuals to acquire a wholesale CBDC indirectly via a bank holding a wholesale CBDC issued by a central bank. If individuals are allowed to hold a CBDC, the amount of CBDC issued should be also included in monetary aggregates that now consist of physical currency held by the private sector and vault cash in banks. This means individuals and private sector economic entities can also hold physical and digital currencies as a means of payment just as banks electronically deposit or hold reserves in the vault or at the central bank.

Although no concrete and substantial plan exists to issue CBDC, many technological alternatives have been presented. Depending on whether the payment and settlement are centralized or distributed, there are two types of CBDCs—a single-ledger type (account-based) where a central bank or a delegated bank keeps record of and manages payment and settlement data, and a distributed ledger type (token-based) where transaction data are distributed to and managed by multiple entities based on blockchain technology. A distributed ledger enables multiple users including a central bank to use a digital wallet to store funds and make transactions, which ensures anonymity on par with physical currency. This is again categorized into authorized and unauthorized types, but the authorized type is in general viewed as a better option as this better secures payment and settlement stability at a time of, for example, transaction cancellation.

Although no developed economy has yet to officialize the issuance of digital currency, many nations have been carrying out a diverse range of research and experiments. As far as is known, Sweden—where the share of cash transactions is declining—is scheduled to decide whether to issue a CBDC called e-krona this year after collecting public opinions. Other developed countries such as the US, Japan, and the UK have yet to formulate any concrete plan. However, Canada and Singapore are working on how wholesale digital currencies are used to help large transactions to be paid and settled more efficiently.

Of emerging economies, those with less population, declining cash transactions, and underdeveloped payment and settlement services such as Uruguay and Tunisia are trying to issue CBDC. One of the notable advances in this area is made by China when it successfully carried out a pilot interbank transaction using its digital currency based on blockchain technology. Based on the success, People’s Bank of China is pushing for a two-tiered digital currency distribution system that consists of one end from the central bank to commercial banks and the other from commercial banks to individual customers. The rationale behind such a move appears to be China’s aspiration to use the system for cross-border transactions for positioning yuan as a global currency.

Impacts and risks of digital currency issuance

If a central bank issues a wholesale digital currency and supplies it only to banks, this will barely impact monetary aggregates or the financial sector as such transactions are expected to take the form of a digital transfer between digital currency and bank reserves. However, a retail digital currency that is supplied to individual economic entities could impose a significant impact on many aspects, for example, payment and settlement convenience, monetary policy efficiency and financial stability. More concretely, the following impacts are expected in the overall financial sector if a retail digital currency is distributed more widely.

First, this is expected to make payment and settlement more convenient and efficient. In many economies, the share of cash holdings or cash settlement tends to be on the decrease. Digital currency against that backdrop could not only cut the risk of theft and loss, but also make payment and settlement faster, easier, and more efficient. Furthermore, CBDC’s status as a legal tender issued by a central bank helps add credibility and makes it differentiated from other forms of digital payment in the private sector. This could surely offer individual economic entities a new, convenient, and safe means of payment. Another beneficial aspect of CBDC is its efficiency as a payment and settlement means for the financially marginalized who are unable to open a bank account or susceptible to digital transactions.

However, a distributed ledger on an anonymity-based operating system—although this is good for protecting private information—could potentially give rise to some side effects such as illegal transactions or underground economic activities. Also, such a system could stand in rivalry with private sector banks’ online banking and other digital payment services, as well as other fintech firms’ online payment and money transfer services. Such an aspect could bring an immense change in the payment service industry.

Second, this could alter the path of monetary policy and the efficacy. On a positive side, a central bank using digital currency could secure a channel via which to quickly supply liquidity (e.g., quantitative easing) to private sector entities. For example, using a digital currency could shorten the time during which a money supply—for example, Korea’s emergency disaster relief funds in response to the Covid-19 pandemic—goes through financial intermediaries to result in a multiplier effect. Digital currency could also help central banks improve the efficacy of monetary policy by lowering the digital currency interest rate to negative levels amid increasing financial unrest or other unusual circumstances.

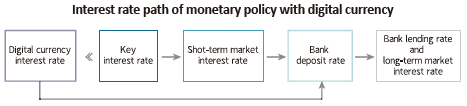

One of the negative aspects is a potential change in the interest rate path of monetary policy, which is expected when a central bank sets an interest rate on digital currency. The level of that interest rate could be somewhere around the key interest rate subtracting the convenience of digital currency circulation, making the interest rate regime of the digital currency rate, the key interest rate, the short-term market interest rate, and the bank deposit rate (arranged in ascending order). This means the digital currency interest rate serves as a lower bound in the short-term money market. In that case, the risk-free interest rate on digital currency could directly affect bank deposit rates, which will further complicate and diversify the interest rate path of monetary policy transmitting to the real economy via long-term interest rates and bank lending rates. The new interest rate regime is also expected to change the short-term money market.

Digital currency with a positive interest rate could be regarded as risk-free financial assets issued by a central bank. This will predispose economic entities to replace bank deposits with digital currency depending on risk preference, which might possibly enfeeble the monetary policy path via bank’s credit provision.

Third, digital currency could adversely impact banks’ intermediation and financial stability. If demand for digital currency replaces that of bank deposits, the resultant cut in private sector bank deposits will raise banks’ financing costs while reducing their lending ability. This could possibly erode their intermediary function and profitability. If met with financial unrest and high levels of risk aversion, demand for digital currency will rise further enough to raise concerns about a digital run where bank deposits shrink abruptly. Banks’ increase in short-term funding such as call money and repo in response could further increase the interconnectedness among financial institutions. Any external shock under the circumstances could further exacerbate the negative impact on financial stability.

It’s possible for a central bank to step in, aiming to help banks with reduced lending capacity via an open market operation to purchase government bonds or additional liquidity provision to lend more to banks. However, both of them will inflate the central bank’s balance sheet, and therefore impose burden on monetary policy operation. Taken together, the magnitude of the impacts mentioned above depends on the size of demand for digital currency among private sector economic entities, and the extent of the fall in bank deposits.

Implications

The issuance of CBDC is expected to not only bring changes in how traditional currency is perceived and used in practice, but also have a wide-ranging impact on a central bank’s critical functions, such as ensuring the stability of payment and settlement, securing the efficacy of monetary policy, and maintaining financial stability. For digital currency to help promote those critical functions while minimizing the adverse impact on financial stability, it’s worth considering the following aspects.

First, payment and settlement efficiency will improve only if safety of the new settlement system comes first in designing the form of issuance. Among others, preparedness for cyber attacks is a must given that blockchain and other novel operating systems are still not fully verified. It’s undesirable for a step towards payment convenience to undermine the stability of the payment system.

Second, extra caution is required for improving the efficacy of monetary policy and keeping financial stability intact. Particularly noteworthy is the possibility where the digital currency interest rate may cause inevitable impacts on short- and long-term financing markets and the monetary policy path. Also possible is that a decline in bank deposits—a major funding source for banks—could enfeeble bank’s intermediary function and profitability. Accordingly, policy effort should be made to thoroughly analyze any change in demand for cash and digital currency, and any decrease in banks’ credit provision.

Third, on top of a technological approach, another important task in the upcoming future is an overhaul in finance-related laws and regulations because CBDC, once issued, will vie with private sector players such as fintech service providers to bring an immense change to the settlement industry. Towards that end, financial authorities need to overhaul the Bank of Korea’s Act that deals with the safety of payment and settlement and currency issuance, while making coordinated effort and closely cooperating with each other in revising other relevant laws such as the Banking Act, and the Electronic Financial Transactions Act.

Given the broad range of impacts on the national economy and the complex process towards CBDC issuance, a cautious approach is required with close monitoring of developments taking place in other countries, and the impacts.

Against the backdrop, this article tries to offer a concise overview on the meanings and current state of CBDC, the impacts and risk factors of the adoption, and the implications of the potential issuance.

CBDC: Meanings and current state

Central banks around the globe are discussing at the moment a form of currency that digitally stores and transfers value for payment and settlement unlike conventional currency taking a physical form. Unlike other cryptocurrencies issued by private sector players, CBDC’s legal tender status makes its conversion rate equivalent to that of physical currency, which effectively eliminates the risk of value fluctuation. Also, its confidence is guaranteed because the issuer is a central bank.

CBDCs can be categorized into two types—a wholesale CBDC issued for banks and other deposit-taking financial institutions, and a retail CBDC issued for individuals and other private sector economic entities. It’s possible for individuals to acquire a wholesale CBDC indirectly via a bank holding a wholesale CBDC issued by a central bank. If individuals are allowed to hold a CBDC, the amount of CBDC issued should be also included in monetary aggregates that now consist of physical currency held by the private sector and vault cash in banks. This means individuals and private sector economic entities can also hold physical and digital currencies as a means of payment just as banks electronically deposit or hold reserves in the vault or at the central bank.

Although no concrete and substantial plan exists to issue CBDC, many technological alternatives have been presented. Depending on whether the payment and settlement are centralized or distributed, there are two types of CBDCs—a single-ledger type (account-based) where a central bank or a delegated bank keeps record of and manages payment and settlement data, and a distributed ledger type (token-based) where transaction data are distributed to and managed by multiple entities based on blockchain technology. A distributed ledger enables multiple users including a central bank to use a digital wallet to store funds and make transactions, which ensures anonymity on par with physical currency. This is again categorized into authorized and unauthorized types, but the authorized type is in general viewed as a better option as this better secures payment and settlement stability at a time of, for example, transaction cancellation.

Although no developed economy has yet to officialize the issuance of digital currency, many nations have been carrying out a diverse range of research and experiments. As far as is known, Sweden—where the share of cash transactions is declining—is scheduled to decide whether to issue a CBDC called e-krona this year after collecting public opinions. Other developed countries such as the US, Japan, and the UK have yet to formulate any concrete plan. However, Canada and Singapore are working on how wholesale digital currencies are used to help large transactions to be paid and settled more efficiently.

Of emerging economies, those with less population, declining cash transactions, and underdeveloped payment and settlement services such as Uruguay and Tunisia are trying to issue CBDC. One of the notable advances in this area is made by China when it successfully carried out a pilot interbank transaction using its digital currency based on blockchain technology. Based on the success, People’s Bank of China is pushing for a two-tiered digital currency distribution system that consists of one end from the central bank to commercial banks and the other from commercial banks to individual customers. The rationale behind such a move appears to be China’s aspiration to use the system for cross-border transactions for positioning yuan as a global currency.

Impacts and risks of digital currency issuance

If a central bank issues a wholesale digital currency and supplies it only to banks, this will barely impact monetary aggregates or the financial sector as such transactions are expected to take the form of a digital transfer between digital currency and bank reserves. However, a retail digital currency that is supplied to individual economic entities could impose a significant impact on many aspects, for example, payment and settlement convenience, monetary policy efficiency and financial stability. More concretely, the following impacts are expected in the overall financial sector if a retail digital currency is distributed more widely.

First, this is expected to make payment and settlement more convenient and efficient. In many economies, the share of cash holdings or cash settlement tends to be on the decrease. Digital currency against that backdrop could not only cut the risk of theft and loss, but also make payment and settlement faster, easier, and more efficient. Furthermore, CBDC’s status as a legal tender issued by a central bank helps add credibility and makes it differentiated from other forms of digital payment in the private sector. This could surely offer individual economic entities a new, convenient, and safe means of payment. Another beneficial aspect of CBDC is its efficiency as a payment and settlement means for the financially marginalized who are unable to open a bank account or susceptible to digital transactions.

However, a distributed ledger on an anonymity-based operating system—although this is good for protecting private information—could potentially give rise to some side effects such as illegal transactions or underground economic activities. Also, such a system could stand in rivalry with private sector banks’ online banking and other digital payment services, as well as other fintech firms’ online payment and money transfer services. Such an aspect could bring an immense change in the payment service industry.

Second, this could alter the path of monetary policy and the efficacy. On a positive side, a central bank using digital currency could secure a channel via which to quickly supply liquidity (e.g., quantitative easing) to private sector entities. For example, using a digital currency could shorten the time during which a money supply—for example, Korea’s emergency disaster relief funds in response to the Covid-19 pandemic—goes through financial intermediaries to result in a multiplier effect. Digital currency could also help central banks improve the efficacy of monetary policy by lowering the digital currency interest rate to negative levels amid increasing financial unrest or other unusual circumstances.

One of the negative aspects is a potential change in the interest rate path of monetary policy, which is expected when a central bank sets an interest rate on digital currency. The level of that interest rate could be somewhere around the key interest rate subtracting the convenience of digital currency circulation, making the interest rate regime of the digital currency rate, the key interest rate, the short-term market interest rate, and the bank deposit rate (arranged in ascending order). This means the digital currency interest rate serves as a lower bound in the short-term money market. In that case, the risk-free interest rate on digital currency could directly affect bank deposit rates, which will further complicate and diversify the interest rate path of monetary policy transmitting to the real economy via long-term interest rates and bank lending rates. The new interest rate regime is also expected to change the short-term money market.

Third, digital currency could adversely impact banks’ intermediation and financial stability. If demand for digital currency replaces that of bank deposits, the resultant cut in private sector bank deposits will raise banks’ financing costs while reducing their lending ability. This could possibly erode their intermediary function and profitability. If met with financial unrest and high levels of risk aversion, demand for digital currency will rise further enough to raise concerns about a digital run where bank deposits shrink abruptly. Banks’ increase in short-term funding such as call money and repo in response could further increase the interconnectedness among financial institutions. Any external shock under the circumstances could further exacerbate the negative impact on financial stability.

It’s possible for a central bank to step in, aiming to help banks with reduced lending capacity via an open market operation to purchase government bonds or additional liquidity provision to lend more to banks. However, both of them will inflate the central bank’s balance sheet, and therefore impose burden on monetary policy operation. Taken together, the magnitude of the impacts mentioned above depends on the size of demand for digital currency among private sector economic entities, and the extent of the fall in bank deposits.

Implications

The issuance of CBDC is expected to not only bring changes in how traditional currency is perceived and used in practice, but also have a wide-ranging impact on a central bank’s critical functions, such as ensuring the stability of payment and settlement, securing the efficacy of monetary policy, and maintaining financial stability. For digital currency to help promote those critical functions while minimizing the adverse impact on financial stability, it’s worth considering the following aspects.

First, payment and settlement efficiency will improve only if safety of the new settlement system comes first in designing the form of issuance. Among others, preparedness for cyber attacks is a must given that blockchain and other novel operating systems are still not fully verified. It’s undesirable for a step towards payment convenience to undermine the stability of the payment system.

Second, extra caution is required for improving the efficacy of monetary policy and keeping financial stability intact. Particularly noteworthy is the possibility where the digital currency interest rate may cause inevitable impacts on short- and long-term financing markets and the monetary policy path. Also possible is that a decline in bank deposits—a major funding source for banks—could enfeeble bank’s intermediary function and profitability. Accordingly, policy effort should be made to thoroughly analyze any change in demand for cash and digital currency, and any decrease in banks’ credit provision.

Third, on top of a technological approach, another important task in the upcoming future is an overhaul in finance-related laws and regulations because CBDC, once issued, will vie with private sector players such as fintech service providers to bring an immense change to the settlement industry. Towards that end, financial authorities need to overhaul the Bank of Korea’s Act that deals with the safety of payment and settlement and currency issuance, while making coordinated effort and closely cooperating with each other in revising other relevant laws such as the Banking Act, and the Electronic Financial Transactions Act.

Given the broad range of impacts on the national economy and the complex process towards CBDC issuance, a cautious approach is required with close monitoring of developments taking place in other countries, and the impacts.