OPINION

- Summary

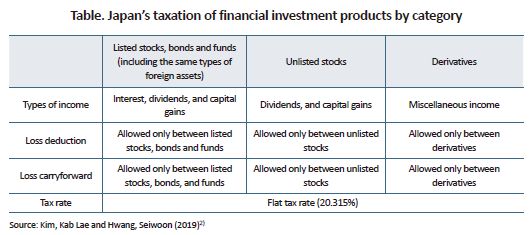

- Reforming capital gains tax on financial investment products, coupled with a cut in securities transaction tax, has come under increasingly heated discussion. It is important to delve into the direction tax changes in other countries are heading in, when discussing the direction of the tax reform. We can draw out useful implications from Japan in particular because of similarities between Japan and Korea. Japan divides financial investment products into three categories and allows loss deduction and loss carryforward between financial investment products within the same category. Through comprehensive loss deduction against different types of income from financial investment products and three-year loss carryforward, Japan’s tax regime for financial investment products seeks to achieve diverse objectives, that is, investment diversification, entrepreneurial capital accumulation, and citizens’ wealth increase via capital markets. The characteristics of Japan’s capital gains taxation would provide some insights into how Korea should continually develop its tax regime for the capital markets.

Korea has lowered its securities transaction tax by 0.05% in June 2019. The tax cut can be seen as a positive shift in the direction of securities taxation for market development because securities transaction tax has been considered as a key component of trading costs in the stock market. Encouragingly, the government also hinted at the possibility of further tax cuts. If we look at global taxation trends, securities transaction tax has gradually been phased out due to higher chances of a market contraction caused by the tax burden. Given declining stock market liquidity and international coherence of taxation, there is a greater need for the abolition of securities transaction tax from a long-term perspective. The removal of the tax all at once could result in tax revenue shortfalls, putting a burden on the government. Hence, a gradual phasing-out of securities transaction tax in the long run would be desirable.

Along with the tax cut, tax on capital gains from financial investment products has been under increasingly heated discussion in the market. In some respects, securities transaction tax was first introduced in lieu of capital gains tax because the taxation infrastructure for profits from stock sales was not sufficiently in place at that time. The recent tax cut and discussions about capital gains taxation appear to move in the right direction of change in the taxation regime, given the taxation principle that where there is income, there is tax.

Taking stock of tax shifts worldwide is important because it would help us minimize trial and error in taxation overhaul and reduce its adverse impacts when discussing the direction of improvement for capital gains taxation of financial investment products. Tax reform discussions, therefore, should involve comparing the relevant tax regimes across countries. Japan’s taxation regime is especially worth noting. The evolutions of Japan’s tax laws and financial markets have enormous impacts on Korea’s legal structure and capital markets, showing high similarity to them. Thus, if we analyze the characteristics and evolution of Japan’s taxation of capital gains from financial investment products, we can draw out some implications for Korea to improve its capital gains taxation in the capital markets. This article examines the characteristics of Japan’s capital gains taxation of financial investment products, and explores the implications of the findings for the direction of improvement for capital gains taxation in the Korean capital markets.

Japan’s capital gains taxation of financial investment products

Japan’s capital gains tax regime for financial investment products has evolved based on a positive list approach. In 1989, the country started to impose tax on capital gains from the sale of stocks incurred by individual investors. As the capital gains tax regime took root, securities transaction tax was abolished in 1999. The evolution of capital gains tax in Japan clearly exhibits the primary objective of the tax reform, that is, to generate tax revenue and facilitate the capital markets’ functions by providing the markets with appropriate incentives.

The Income Tax Act and the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation are the two fundamental tax laws governing the taxation of capital gains from financial investment products. One of the key characteristics observed in the taxation is that Japan divides financial investment products into three categories, i) listed stocks, bonds, and funds, ii) unlisted stocks, and iii) derivatives (including derivative-linked products), and imposes capital gains tax on each of the product categories accordingly. When looking at Korea’s taxation policy, there has been no obvious attempt to distinguish listed and unlisted stocks. However, Japan differs from Korea in the sense that it classifies listed and unlisted stocks into different categories to impose capital gains tax despite their economic similarities. Another characteristic is that assets in the same category, regardless of whether they are domestic or foreign, are subject to the same capital gains tax rate. In Korea, minority shareholders are not subject to capital gains tax on profits from direct investment in stocks listed on domestic exchanges, but it is not the case for profits from direct investment in stocks listed on foreign exchanges. In Japan, on the other hand, capital gains tax is imposed on stocks listed on either a domestic or foreign exchange in the same manner.

Income from listed stocks, bonds, and funds includes interest, dividends and capital gains. These three types of income are subject to the same tax rate of 20.315% in total, including 15% income tax, 5% local tax, and 0.315% special restoration income surtax. The application of a flat tax rate to the three different types of income is an economically rational approach considering that interest could be turned into dividends or capital gains due to advances in financial engineering. The tax base associated with capital gains is calculated by subtracting the costs involved in acquiring and transferring a financial investment product, and borrowing expenses such as interest from proceeds from the sale of the investment product. The capital gains determined are taxed at a flat rate, separately from other sources of income. In principle, investors must report their gains and pay the tax under the self-assessment system. To alleviate investors’ burden associated with tax filing and payments, the Japanese government grants an individual investor exemptions from the tax filing and payment requirements when a financial institution withholds the 20.315% tax from the investor’s capital gains kept in his or her specified or designated account. This scheme was introduced in 2002 to allow investors to open one specified or designated account with one financial services firm for either streamlined tax filing or tax withholding. If the investor chooses to open an account for streamlined tax filing, the financial services firm calculates annual profits from transactions and taxes, preparing and delivering an annual statement of transactions to the investor. Then, the investor files this statement with the National Tax Agency. If the investor chooses to open an account for tax withholding, the financial services firm withholds taxes from the investor’s capital gains arising from each transaction, which are kept in his or her designated account, discharging the investor’s tax liability. The investor, therefore, does not need to report his or her capital gains to the tax authority.1) But if the investor wants to qualify for loss deduction against income from other accounts or loss carryforward, the investor must file a tax return himself or herself and pay the tax directly to the tax authority.

Furthermore, there are no differences between unlisted shares and listed shares in terms of the way the tax base is computed, and tax rate levels, except that the use of a specified or designated account is not allowed for unlisted shares. Dividends or capital gains from unlisted shares are taxed at the rate of 20.315%, and investors must submit their tax returns under self-assessment. Income from derivatives is classified as miscellaneous income, which is distinguished from income from listed shares, bonds, and funds or income from unlisted shares. Taxable miscellaneous income from derivatives is computed in the same way as taxable income from listed shares, subject to the same tax rate of 20.315%.

Structure of loss deduction and loss carryforward

Japan allows loss deduction and limited loss carryforward for capital gains from financial investment products. If net capital gains are positive as a result of the tax base calculation, tax is levied on the gains. If net capital losses occur, the losses can be carried forward only for a limited period of time. The scope of loss deduction varies depending on categories of financial investment products set out in the Income Tax Act and the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation. To be more specific, loss deduction between listed stocks, bonds, and funds is allowed, meaning that capital losses can be offset against earned interest, dividends, and capital gains from listed stocks, bonds, and funds. Loss deduction between unlisted stocks is also available, implying that capital losses can be deducted against dividends and capital gains from unlisted stocks. The same is true for miscellaneous income from derivatives.

One notable characteristic of Japan’s loss deduction is that loss deduction is permitted only between financial investment products within the same category specified by laws. In other words, loss deduction is available between listed stocks, bonds and funds, but not between listed and unlisted stocks. Not only that, loss deduction is neither allowed between listed stocks and derivatives nor between unlisted stocks and derivatives. In addition, capital losses can be deducted against interest or dividend income, which sets Japan’s capital gains tax regime apart from Korea’s tax regime.

Overall, Japan’s loss deduction between financial investment products is viewed as a more flexible approach than Korea’s loss deduction. In Korea, loss deduction is allowed only between stocks or between derivatives, while it is available within one fund, not between funds. In Japan, losses can be deductible across listed stocks, bonds and funds, indicating the wider scope of loss deduction in Japan than in Korea. Furthermore, Korea allows capital losses to be deducted only against capital gains whereas Japan allows capital losses to be offset against capital gains, interest and dividends. That suggests that more diverse types of income are eligible for loss deduction in Japan than in Korea.

Japan also takes a more flexible approach to loss carryforward than Korea. In Japan, limited loss carryforward is allowed for net capital losses that occur after losses are deducted against income from financial investment products within the same category. In this regard, Japan stands in stark contrast to Korea where loss carryforward is not permitted under the current tax regime. Japan allows investors to carry forward net capital losses from listed stocks, bonds and funds, unlisted stocks, or derivatives to subsequent three years to deduct against future gains. But Japan does not allow loss carrybacks.

Implications for Korea’s capital gains taxation in the capital markets

Japan’s taxation of financial investment products can be summarized as follows: i) financial investment products are classified mainly into three categories pursuant to the relevant tax laws; ii) loss deduction and loss carryforward are allowed for financial investment products within the same category; iii) the single tax rate of 20.315% is applied to interest, dividends and capital gains so as to simplify tax rates and minimize distortions in relation to cash flows caused by tax-rate differentials. The table below outlines the characteristics of Japan’s taxation of financial investment products.

We can draw the following implications from Japan’s capital gains taxation described above for advancing Korea’s capital gains taxation in the capital markets: First, Japan exhibits more flexibility in the scope of loss deduction between financial investment products, allowing capital losses to be deducted against capital gains from listed stocks, bonds and funds. In Korea, by contrast, loss deduction is allowed only between stocks, or only within a fund rather than between funds. This means that the scope of loss deduction is wider in Japan than in Korea. However, loss deduction between listed stocks and derivatives, or between listed and unlisted stocks is not allowed in Japan, as in Korea. When the capital market structure and investor base structure are taken into account, loss deduction between listed stocks, bonds and funds can be considered a more flexible taxation approach. Allowing loss deduction for the broader range of financial investment products would be desirable in that this can play a part in supporting investors’ diversification and investment in entrepreneurial capital.

Second, capital losses are subject to the three-year carryforward in Japan. It means that capital losses can be deductible against future capital gains from financial investment products in the same category in subsequent three years. This is important for entrepreneurial capital investment. This investment, for most part, is highly likely to incur losses in the early stage. Further, in many cases, it takes a long time to exit the investment. The absence of loss carryforward would more likely dwarf entrepreneurial capital investments below appropriate levels. Japan allows capital losses to be carried forward only for three years due to concerns over a decline in tax revenue that may result from a long-term carryforward period. Korea, on the other hand, does not permit loss carryforward for financial investment products. Given the need to enhance the role of the capital markets as a provider of entrepreneurial capital, the introduction of loss carryforward is worth considering for the capital gains taxation of financial investment products.

Third, Japan also allows loss deduction against interest and dividend income, as well as capital gains from financial investment products. Loss deduction against interest and dividends in addition to capital gains is permitted for listed stocks, bonds and funds. And loss deduction against dividends as well as capital gains is available for unlisted shares. For derivatives, loss deduction only against miscellaneous income is allowed. As advanced financial techniques increasingly enable dividend or interest income to be transformed into capital gains, loss deduction against not only capital gains but also interest and dividends would be rational in the economic sense.

Japan’s tax regime for financial investment products has continued to evolve with the objectives of reviving its tepid economic growth amid population aging and supporting citizens’ wealth increase by facilitating the accumulation of entrepreneurial capital and propping up the growth of innovative venture businesses. Japan’s taxation of financial investment products can serve as a useful guide for Korea to further develop its tax regime for the capital markets considering that Japan’s demographics and economic growth trajectory are similar to Korea’s.

1) See Article 37.11.3 (Special provisions for taxation on capital gains, etc. related to listed shares, etc. in custody in specified account), and Article 37.11.4 (Special provisions for withholding, etc. on income, etc. from transfer of shares, etc. in custody in specified account) of the Act on Special measures Concerning Taxation in Japan.

2) Kim, Kab Lae, and Hwang, Seiwoon, 2019, The US and Japanese tax regimes for loss deduction between financial investment products, and their implications, KCMI Issue Paper 19-03.