OPINION

- Summary

- At the wake of massive losses in DLF products in Korea, there’re increasing voices calling for tougher regulation on distribution channels of retail structured products. A comparative look at the regulation between Korea and selected developed countries reveals that regulatory arbitrage appears to be insignificant, although sizable differences are observed in the level of sanctions and the fee scheme. Based on the findings, this article proposes five regulatory improvements that are expected to steer Korea’s retail structured product market in desired directions. First, a mis-selling fine should be introduced immediately. Second, it’d better shift the current upfront, commission-based scheme towards a fee-based scheme linked to performance. Third, it’ s necessary to strengthen the suitability principle and post-sales practices for sales of privately placed funds. Fourth, financial advisers selling structured products should be obligated to meet tougher qualifications. Fifth, regtech and other tools are needed to bolster compliance in terms of the sales process in banking channels.

A retail structured product refers to a financial vehicle that pays out returns higher than those on savings unless there's a significant increase or decrease in underlying assets such as stock indexes, interest rates, commodity prices, etc. When low interest rates prolong and expected returns on traditional assets are declining, they emerge as an attractive alternative. Equity-linked securities (ELS), derivatives-linked securities (DLS), and other retail structured products have inherent tail risk that provides higher returns at normal times, but massive losses at crises. Hence, they may be suitable for risk-seeking (aggressive) investors who could bear such large losses, but not for risk-adverse (conservative) investors who are unable to bear the risk.

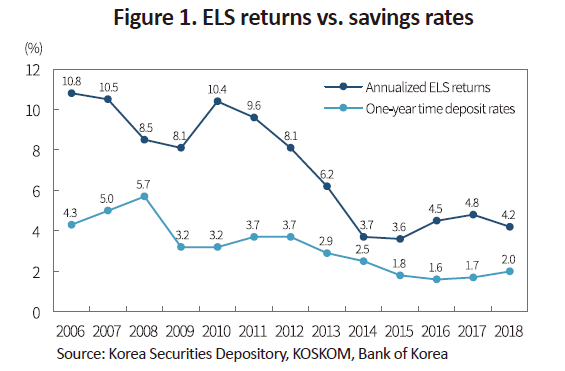

Since the low interest rate became the global norm around the 2000s, the sales of retail structured products shot up in the US, Europe, and Asia. Korea first introduced publicly offered ELS in 2003 with the reform on the Enforcement Decree of the former Securities and Exchange Act. Since then, the market for retail structured products has grown rapidly, compared to other developed countries. Korea’s growth was fast-paced due to three reasons. First, ELS and DLS outperformed bank savings (refer to Figure 1). Second, retail structured products were packaged as trusts and private equity funds to be readily distributed via bank sales channels. Third, reinvestment is made easy because the automatic early redemption shortens the actual maturity to less than one year, much shorter than bank savings.

As the underlying indexes plummeted at the wake of the global financial crisis, many retail structured products sold in major developed countries incurred heavy losses. At that time, there were many mis-selling cases where the duty to explain or the suitability principle were improperly enforced during the sales process. This triggered developed markets such as the US, UK, and Hong Kong, and European countries to substantially toughen regulation on retail structured products.1) In 2013, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) unveiled the regulatory guidelines on retail structured products that include regulatory principles on disclosures, sales, and post-sales practices for the protection of investors. Korea is no exception to such regulatory moves. The 2008 global financial crisis, the 2013 Tongyang corporate bond debacle, and the 2016 plunge in Hong Kong’s H-shares index shed light on the possibility of mis-selling of ELS and DLS products, eventually leading to toughening of regulation on the production, disclosures, sales, and post-sales practices.2)

Arguably, the recent mis-selling issue around derivatives-linked funds (DLF) threw us an important question. How could this happen although Korea toughened regulation on distribution channels of retail structured products? Fundamental causes that could be assumed to have raised the problem could either rising demand in the era of low interest rates, the problems in bank sales channels, or regulatory gaps between Korea and developed countries. With the focus placed on regulatory gaps compared to developed countries, this article tries to have a comparative analysis on regulation on retail structured products in Korea and developed countries, from which to draw regulatory directions to steer Korea’s retail structured product market in desired directions.

IOSCO guidelines

For the purpose of stronger investor protection, IOSCO presented in the Regulatory Toolkit3) containing a total of 15 regulatory tools for the issuance, sales, and post-sales practices regarding retail structured products. First of all, financial authorities should try to minimize regulatory arbitrage across markets (Regulatory Tool 1), and better understand the value chain of retail structured products (Regulatory Tool 2). Product issuers need to provide suitable products taking into account investors’ risk appetite, investment objectives, and investment timeframe (Regulatory Tool 3), with possible scenarios based on stress tests and other tools (Regulatory Tool 4). They need to design products that prevent any conflict of interests between issuers and investors (Regulatory Tool 5), and make endeavor for product standardization (Regulatory Tool 6).

With regard to disclosure, IOSCO set out seven regulatory principles. Issuers should provide product structures and risks in a way that is easily understandable for investors (Regulatory Tool 7), and offer a short-form summary (Regulatory Tool 8). The disclosure should provide disclosures of fees and charges that are separated into components related to issuance, sales, redemption, etc. (Regulatory Tool 9) based on fair value assessment (Regulatory Tool 10). Also, risks of profits and losses should be presented under hypothetical scenarios (Regulatory Tool 11). Issuers should also consider carrying out backtesting based on past data on underlying indexes (Regulatory Tool 12). For the sake of investor protection, they should be able to carry out investor education (Regulatory Tool 13).

Last, the toolkit suggests the principles governing distribution channels and post-sales practices. To minimize mis-selling, distributors should strictly abide by the compliance standards, the duty to explain, and the suitability requirements set forth in their jurisdiction (Regulatory Tool 14). Also required are regulatory measures covering the periods after product distribution, including cooling-off periods, guidance at the maturity of the product, keeping investors informed with key information such as their ability to dispose of the product, resolution of investor complaints, etc. (Regulatory Tool 15).

US regulation

The US has governed disclosures and distribution of retail structured products with both self and statutory regulations. SEC Rule 10b-5 prohibits the employment of manipulative and deceptive practices. Any breach is subject to administrative sanctions such as a fine or civil liabilities under SEC Rule 10b-5. Also in place are self-regulation such as the FINRA Rule 2090 (Know Your Customer), 2011 (Suitability), and 2114 (Recommendations to Customers in OTC Securities), which stipulate the basic principles in sales of retail structured products. More concretely, distributors of retail structured products need to take into account their customers’ risk tolerance and asset portfolio before recommending a suitable product. When selling retail structured products over-the-counter, distributors should meet certain requirements needed to accurately recognize the risks inherent in those products. Sellers can recommend products with options to investors as long as the investors have similar investment experience or are able to bear the inherent risk.

US regulation is similar to that of IOSCO and Korea. It differs from Korea’s regulation in that offenders are subject to heavy fines and civil liabilities. Also, it applies the suitability principle to not only retail investors, but also institutional investors who meet certain criteria. For the sake of protecting senior investors aged 65 or higher, the US in 2018 adopted two rules, including FINRA Rule 2165 where financial firms can temporarily hold on a disbursement when they believe or have doubt about any financial exploitation, and FINRA Rule 4512 where financial firms need to have the name and contact information of the associated person.

UK and European regulation

In the case of the UK, the Conduct of Business Sourcebook (COBS) sets forth the duty to explain (Chapter 6, 13, and 14), the Know Your Customer Rule (Chapter 9), and the suitability principle (Chapter 9). Although UK regulation is similar to that of Korea and IOSCO, it is more like US regulation as it allows fines on offenders. Also distinctive from Korea’s regulation is the mandated submission of a suitability report by a distributor to a retail investor.4) After retail structured debt had incurred massive losses in the 2000s, the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) was adopted in 2012. Under the RDR, high-risk products should be sold through the independent financial adviser (IFA) channel that receives a fee from clients, not a commission from producers. Also, the RDR tried to pursue tougher seller requirements, stronger disclosures on the remuneration system, advisers carrying out the suitability test on a regular basis, provision of post-sales services. In the post-RDR era, a decline has been reported in the sales of high-risk structured products charging high upfront fees, despite an increase in the sales of low-fee products such as ETFs.

Meanwhile, Europe regulates investor solicitation via the suitability principle, etc. under MiFID II. Sales of retail structured products have been regulated in full since January 2019. Article 16(2), 25(2), 54(2), 54(5), etc. in MiFID II prescribe the Know Your Customer and Know Your Product rules, the duty to explain, and the suitability principle. Although MiFID II is similar to Korea’s and IOSCO regulation, it requires retail investors to submit the suitability report, which is similar to the UK case. Also distinctive is the inclusion of sales practices via robo advisers. For enhanced prudence in disclosures and distribution channels of retail structured products, it has a separate rule called the Packaged Retail Insurance-based Investment Products (PRIPS) Regulation, which came into full effect in 2018. PRIPS Regulation stipulates the distribution of investment funds, retail structured products, life insurance funds with an investment element, structured deposits, in which distributors should provide the key information document displaying a product’s risk, costs, maximum loss, etc., and comply with requirements such as the duty to explain and the cooling off period. As are the cases of the UK and the US, the distributor or the adviser is imposed a tough fine in the case of any violation.

Hong Kong regulation

In Hong Kong, the Business Conduct in Division 2 of Part VII in the Securities and Futures Ordinance enacted by the Securities and Futures Commission explicitly states the duty to explain and a ban on improper investor solicitation. Hong Kong has toughened regulation on retail structured products since minibonds missold by leading banks incurred massive investment losses at the height of the 2008 global financial crisis. In the first half of 2010, a regulation was enacted to govern retail structured products,5) which mandates distributors to offer clients a two-day cooling off period as well as a document including information such as the risk, costs, payout structure of retail structured products. Also, distributors are obligated to audio record the risk assessment process in case of any mismatch between an investor’s risk appetite and the actual product risk. Hong Kong’s regulation does impose a massive mis-selling fine, which is noteworthy. Other than that, there are no marked differences from IOSCO and Korea’s regulatory principles.

Korea’s regulatory future

The brief overview on retail structured product regulations in IOSCO and selected developed countries demonstrates that regulatory arbitrage between Korea and developed countries appears to be insignificant in most areas from disclosures, distribution, post-sales practices, etc. Rather, Korea places tougher distribution rules, compared to developed countries. For example, distributors have to notify investors in publicly offered investment products of a loss of principal or a degraded credit risk. Also, they should offer a cooling off period while audio recording the sales process involving senior investors as well as unqualified investors. Among others, developed countries haven’t placed any regulation on ELS and DLS hedging, although Korea mandates tougher investment management rules such as the separation of hedging assets from principal assets, and the inclusion of sound hedging assets, etc.

Another difference worth mentioning between Korea and developed countries is Korea’s lightness of sanctions that exclude a fine system. Also notable is Korea’s fee scheme that heavily centers on upfront fees, which is highly likely to dispose distributors to prioritize their own interests ahead of investor benefits. Although the UK and Europe mandate the submission of the suitability report to retail investors, Korea does so for only new investors and senior investors aged 70 or higher.

Despite many similarities, the possibility of regulatory arbitrage still lingers in Korea as seen in the ELS and DLS case where the products with a uniform structure were privately placed without proper investor protection such as the suitability principle, the duty to provide the suitability report, the cooling off period, and the post-sales notification of increased risk, etc. Also observed in the DLF debacle are some cases where banking channel sellers recommended DLFs to a number of senior investors for profits from sales loads without properly recognizing the inherent risk. Such non-compliance of the duty to explain and the suitability principle is criticized as another problem.

Against the backdrop, I propose five regulatory directions that would shift Korea’s retail structured product market towards a better future. First, it’s advisable to introduce a mis-selling fine immediately, and the level of fines must be raised substantially, for example, to as large as three times the mis-selling profits. Second, it’d better model after the cases of the UK and Europe, and consider shifting away from the current commission-based scheme towards a fee-based system at least for high-risk products. Because high-risk products in general charge higher sales loads, banking channels are likely to recommend those products, instead of placing their focus on the risk and suitability of such products. Third, when ELS and DLS are placed privately without any regulatory protection such as the suitability principle of post-sales practices, this is prone to regulatory arbitrage. Regulatory tools such as the suitability principle, the submission of the suitability report, the cooling off period, post-sales notifications, etc. should be able to kick in as long as investors in private placement want. Fourth, it’s recommended to eliminate regulatory arbitrate between ELS, DLS, and ELT sellers and those selling privately placed ELF and DLF, for example, by requiring the seller of privately placed ELF and DLF to be the Certified Derivatives Investment Advisor as well. Last but not least, it’s required to bolster compliance via regtech, etc. so that banking channels fully comply with investor solicitation regulation.

1) Nam, Gilnam et al., 2012, Stronger Protection of ELS and DLS Investors, FSC-commissioned Research.

2) Lee, Hyo Seob, 2017, Financial Risks from Increasing ELS and DLS: Diagnosis and Implications, KCMI Research Paper 17-04.

3) IOSCO, 2013, Regulation of Retail Structured Products.

4) Korea mandates the submission of the suitability report to new investors or senior investors aged 70 or higher buying ELS, DLS, and publicly offered ELF and DLF.

5) SFC, 2010, Code of Unlisted Structured Investment Products.