OPINION

2020 Aug/04

Korea’s Green New Deal and Challenges Ahead of Capital Markets

Aug. 04, 2020

PDF

- Summary

- Recently, Korea’s government has unveiled the Green New Deal policy in its move to overcome social and economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, and ultimately to reshape the economy to be a leading power. Governments in developed economies and private sector financial firms have already set clear goals such as tackling climate change and shifting towards renewable energy in their effort to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Towards that end, they have vigorously engaged in socially responsible investing, for example, issuing a large volume of green bonds, and investing heavily in green infrastructure. It’s time for Korea’s financial services firms to engage more in issues such as climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition by giving their support to the Green New Deal policy. This can be done by investing more human and physical capital in key environmental issues. More concretely, they need to internalize those issues in their mid- to long-term business objectives, and accordingly to increase their SRI in green bond issuance and other carbon-neutral projects. Also, further effort should be made to develop a Green New Deal index and a systematic rating system that assesses the environmental category of ESG scores, while launching more financial investment products linked to the Green New Deal. Last but not least, they need to work hard on promoting derivatives on emissions rights, which will eventually help cut greenhouse gas emissions and stabilize the emissions trading market.

Take action for a Green New Deal

There have been calls for a systematic response to climate change and environmental crisis amid the effort to combat the spread of the epidemic such as the Covid-19 and to achieve sustainable economic growth. For years, several nations have implemented concrete plans to cut their greenhouse gas emissions and shift towards renewable energy in response to climate change. In December 2019, the European Union unveiled a European Green Deal which vowed to invest at least 1 trillion euro in every ten years with an aim to meet its carbon neutrality goal of cutting carbon dioxide emissions to zero by 2050. The UK, a country that legislated the 2008 Climate Change Act for the first time in the world, recently passed the amendment to the law and explicitly set a net zero emission target.1) In December 2015, France enacted the energy and climate law that aims to reduce the use of fossil fuel to 60% of the 2012 level by 2030, and to oblige every household to measure and manage their energy efficiency from 2022. In the US, state governments have made every effort to effectively respond to climate change although the federal government declared to leave the Paris Agreement.2) New York City decided to withdraw its investment in any pension fund with carbon-based interests, while the state of California extended its emissions trading program to 2030 and unveiled its plan for a zero carbon dioxide emission. In compliance with the Paris Agreement, China also announced its plans to cut its carbon emissions per GDP by 60% to 65% from the 2005 level by 2030, and to expand its emission rights trading scheme to the whole nation from 2020.

More recently, the Korean government also followed suit and unveiled the Green New Deal, seeking to be better prepared for climate change and environmental crisis and to reshape its economy to be a leading power. In Korea’s path to a more carbon-neutral society, the deal proposes a shift towards greener cities, spaces, and living infrastructure; an increase in low-carbon and distributed energy; and an innovative ecosystem for green industries.3) Arguably, Korea’s Green New Deal policy moves are not only important, but also timely opportune for Korea to overcome social and economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and to achieve sustainable economic growth. However, government effort alone is not enough to achieve intended policy objectives. In Europe, the US, and other leading economies, not only the government and the parliament, but also private sector financial firms often set greenhouse gas emission cuts as their first business priority, and make every effort to carry out socially responsible investing, for example, issuing green bonds, building more green infrastructure, etc. They are actively engaged in emission reduction by vigorously trading carbon emission rights, and investing in urban regeneration projects towards environment-friendly energy consumption. In this critical juncture, this article explores how financial firms in developed countries are dealing with the issue, and tries to figure out what challenges Korea’s capital markets are facing with regard to Korea’s Green New Deal policy.

Green New Deal effort by global financial firms

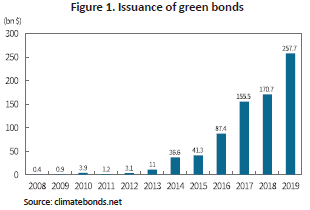

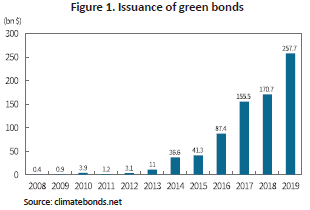

Global financial firms and other private sector firms have been putting massive investments in environment-friendly projects in their response to climate change and environmental crisis. Because those projects require massive funds for a long period of time, they usually issue bonds called green bonds. Since first issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007, green bonds were popular mostly among international organizations such as the World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and Asian Development Bank in the 2010s. In 2014, a total of 13 global investment banks including Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and Deutsche Bank announced the Green Bond Principles that set out guidelines on more stringent reporting, transparency, and disclosure, with an aim to facilitate green bonds. The issuance of those bonds shot up rapidly mostly among private sector financial firms with a jump in demand for green projects and pension funds’ SRI after the 2015 Paris Agreement. Hovering around $1 billion to $3 billion right after the global financial crisis, the issuance of green bonds recorded an 100-fold increase during the subsequent decade to reach $257.7 billion (about KRW 310 trillion) in 2019 (Figure 1).

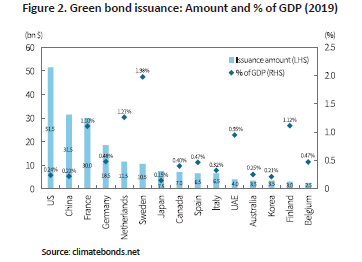

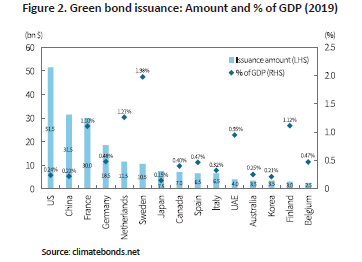

By nation, the issuance remained quite high in developed and European economies including the US, China, France, Germany, etc. As of 2019, green bond issuance accounted for 1% of GDP in major European nations, while the figure stood at only 0.2% in Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, China, etc. (Figure 2). For the year of 2019 alone, there were a total of 1,788 green bond issuance deals by 496 issuers, of which the largest proportion (50%) of the issuers were private sector financial and non-financial firms. Between 2018 and 2019, global private sector firms issued green bonds worth of $110 billion, while European investment banks and Chinese banks were reportedly more active issuers more recently.4) Green bonds issued in 2019 were invested in new and renewable energy (31%), green infrastructure (30%), green mobility (20%), and water quality improvement (9%).

Alongside with green bond issuance, financial firms in Europe have set emission reduction as their business priority and accordingly made firm-wide effort to allocate resources to tackle climate change. Recently, ECB President Lagarde unveiled its green quantitative easing program with an asset purchase plan worth of EUR 2. 8 trillion in its response to climate change.5) Other European investment banks have also carried out massive SRI in climate-focused projects, while announcing plans to cut their investment in a sector that induces either directly or indirectly carbon dioxide emissions. HSBC and Barclays, both headquartered in the UK, put the goal to become a net zero bank as their top business priority. Both of those banks made moves to slowly reduce their investment in fossil fuel sectors that induce greenhouse gas emissions, and to build massive SRI funds for creating a climate-friendly ecosystem via which to achieve sustainable growth. A case worth noting is BNP Paribas that has been remarkable in the area of SRI for years with its goal of emission reduction and renewable energy. In particular, its sustainability linked loan product gained popularity as it offers a discount in interest payments if the borrower makes improvement in climate change effort or the ESG score.

US investment banks have engaged in massive SRI projects as well in their move to respond to climate change, build green infrastructure, and shift towards new and renewable energy. JP Morgan recently published a report on its environmental and social policy framework to better deal with climate change and protect the environment and ecosystems.6) In the report, the bank reaffirmed its commitment to the Paris Agreement and unveiled its plans to give financial support via SRI to sectors that are working on cutting greenhouse gas emissions and switching to new and renewable energy. Also, it pledged to stop financing firms related to fossil fuel burning, deforestation, Arctic development, and other environmental degradation. At the end of 2019, Goldman Sachs also unveiled a plan to invest $750 billion in climate-friendly projects for the next ten years. In its recently released report on the green economy, it projected that clean tech would facilitate new investments worth of $1 trillion–$2 trillion and create 1,500–2,000 new jobs, leading economic recovery and sustainable growth in the post-Covid-19 era.7) Other players such as Bank of America and Citigroup have also unveiled environment and sustainable reports to announce their initiatives to increase their loan and investment for cutting greenhouse gas emissions, building green infrastructure, and shifting towards new and renewable energy.

Overseas cases in response to the Green New Deal

The EU has implemented the carbon emission rights trading scheme since 2005 as part of its emission-cutting effort.8) As of 2020, around 40 countries already launched or plan to launch the emissions trading scheme, which will expand to more emerging economies such as China as recommended by the 2015 Paris Agreement. In 2019 alone, carbon emissions of 14.5 billion tons were traded on the EU Emission Trading System (EU ETS), which is a 4.6-fold increase from 3.1 billion tons in 2013.9) During the same period, prices of emission allowances in Europe jumped 7.4-fold to EUR 25 from EUR 3.4. What’s notable in Europe’s carbon dioxide emission allowances is the vigorous trading not only in the spot market, but also in the derivatives market. Futures and options on emission allowances in Europe are traded actively on exchanges such as the ICE, with their trading value reaching 12-fold of the spot market as of 2019. Korea’s emission trading market has been in operation by the Korea Exchange since 2015. Since reaching 1.24 million tons in the first year of 2015, the market’s trading volume steadily rose to 16.95 million tons in 2019. It’s too bad that derivatives on emission rights do not take fully hold in Korea, which leads to illiquid emission trading with high price volatility.

Global financial firms and stock index operators are equipped with a system that assesses firms’ effort to respond to climate change, expand green infrastructure, and shift towards new and renewable energy, based on which a Green New Deal index can be systematically computed. Global leading operators such as MSCI and S&P Global have already unveiled a separate climate transition index, while asset managers such as Lyxor launched ETFs on climate change indices. And those products have thus far performed well. Furthermore, those index operators and global IBs assess firms’ effort to tackle climate change and to switch to new and renewable energy, for reflecting the results into the environment category of ESG scores.

Challenges ahead of Green New Deal

Governments in Europe and major developed economies such as the US have already established concrete goals and invested massive funds in projects related to climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition that are expected to help the globe to weather the social and economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and to achieve sustainable growth. More recently, the Korean government also unveiled plans to invest a total of KRW 73.4 trillion in the Green New Deal projects for the next five years, which is expected to create 659,000 jobs. It would have been much better if Korea’s financial services and investment companies have shown keen interest in the issues such as climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition, or if they have invested largely in green projects. According to the Climate Change Performance Index of 2019 compiled by GARP to measure how economies around the globe are responding to climate change, European countries ranked high while Korea ranked lower at 58th, clearly lagging behind in this issue. Korea’s financial services and investment industry should invest more of their human and physical capital in the Green New Deal because doing so fits well for the industry’s stated mission to help firms raise risk capital and achieve sustainable growth of private sector firms.

Based on what’s discussed thus far, I propose some of the challenges ahead of Korea’s capital markets towards the success of Korea’s Green New Deal. First, financial services firms need to take note of the cases of global investment banks for devising their mid- to long-term business objectives that include concrete goals regarding climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition. A strategy worth considering is to cut financing to firms that are highly likely to induce carbon emissions and destroy ecosystems. Second, issuing and underwriting green bonds need to take fully hold so that more investments flow to green projects for emission reduction, urban regeneration, renewable energy transition, etc. It’s worth considering the public sector providing guarantees when a private sector financial services firm participates in a high-risk, carbon-friendly project. Third, also necessary includes an index linked to climate change responses and renewable energy transition, and ETFs and other related financial investment products. It’s also advisable to include green infrastructure in REITS assets, which is expected to facilitate publicly-offered financial investment products related to the Green New Deal. Fourth, a research report, or any system that assesses the environmental factors in ESC scores on a regular basis could encourage Korean firms to pay more attention to key climate change issues. Fifth, listing and trading of derivatives on carbon emission rights will surely help effectively reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stabilize the emission trading market.

1) Refer to https://www.gov.uk/government.

2) Ministry of Environment, October 22, 2019, Second basic plan for climate change response, Press Release.

3) Ministry of Economy and Finance, July 14, 2020, Government announces overview of Korean New Deal, Press Release.

4) As of 2019, the largest issuer of green bonds was Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, followed by China’s Industrial Bank, Crédit Agricole, and BNP Paribas.

5) FT News, July 2020, Lagarde Puts Green Policy Top of Agenda in ECB Bond Buying.

6) JP Morgan, February 2020, Environment and social policy framework.

7) Goldman Sachs, 2020. 6, Carbonomics: The green engine of economic recovery.

8) Refer to Key Issues in Global Emission Trading Market in 2018 (Ministry of Environment, 2019).

9) https://icapcarbonaction.com

There have been calls for a systematic response to climate change and environmental crisis amid the effort to combat the spread of the epidemic such as the Covid-19 and to achieve sustainable economic growth. For years, several nations have implemented concrete plans to cut their greenhouse gas emissions and shift towards renewable energy in response to climate change. In December 2019, the European Union unveiled a European Green Deal which vowed to invest at least 1 trillion euro in every ten years with an aim to meet its carbon neutrality goal of cutting carbon dioxide emissions to zero by 2050. The UK, a country that legislated the 2008 Climate Change Act for the first time in the world, recently passed the amendment to the law and explicitly set a net zero emission target.1) In December 2015, France enacted the energy and climate law that aims to reduce the use of fossil fuel to 60% of the 2012 level by 2030, and to oblige every household to measure and manage their energy efficiency from 2022. In the US, state governments have made every effort to effectively respond to climate change although the federal government declared to leave the Paris Agreement.2) New York City decided to withdraw its investment in any pension fund with carbon-based interests, while the state of California extended its emissions trading program to 2030 and unveiled its plan for a zero carbon dioxide emission. In compliance with the Paris Agreement, China also announced its plans to cut its carbon emissions per GDP by 60% to 65% from the 2005 level by 2030, and to expand its emission rights trading scheme to the whole nation from 2020.

More recently, the Korean government also followed suit and unveiled the Green New Deal, seeking to be better prepared for climate change and environmental crisis and to reshape its economy to be a leading power. In Korea’s path to a more carbon-neutral society, the deal proposes a shift towards greener cities, spaces, and living infrastructure; an increase in low-carbon and distributed energy; and an innovative ecosystem for green industries.3) Arguably, Korea’s Green New Deal policy moves are not only important, but also timely opportune for Korea to overcome social and economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and to achieve sustainable economic growth. However, government effort alone is not enough to achieve intended policy objectives. In Europe, the US, and other leading economies, not only the government and the parliament, but also private sector financial firms often set greenhouse gas emission cuts as their first business priority, and make every effort to carry out socially responsible investing, for example, issuing green bonds, building more green infrastructure, etc. They are actively engaged in emission reduction by vigorously trading carbon emission rights, and investing in urban regeneration projects towards environment-friendly energy consumption. In this critical juncture, this article explores how financial firms in developed countries are dealing with the issue, and tries to figure out what challenges Korea’s capital markets are facing with regard to Korea’s Green New Deal policy.

Green New Deal effort by global financial firms

Global financial firms and other private sector firms have been putting massive investments in environment-friendly projects in their response to climate change and environmental crisis. Because those projects require massive funds for a long period of time, they usually issue bonds called green bonds. Since first issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007, green bonds were popular mostly among international organizations such as the World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and Asian Development Bank in the 2010s. In 2014, a total of 13 global investment banks including Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and Deutsche Bank announced the Green Bond Principles that set out guidelines on more stringent reporting, transparency, and disclosure, with an aim to facilitate green bonds. The issuance of those bonds shot up rapidly mostly among private sector financial firms with a jump in demand for green projects and pension funds’ SRI after the 2015 Paris Agreement. Hovering around $1 billion to $3 billion right after the global financial crisis, the issuance of green bonds recorded an 100-fold increase during the subsequent decade to reach $257.7 billion (about KRW 310 trillion) in 2019 (Figure 1).

By nation, the issuance remained quite high in developed and European economies including the US, China, France, Germany, etc. As of 2019, green bond issuance accounted for 1% of GDP in major European nations, while the figure stood at only 0.2% in Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, China, etc. (Figure 2). For the year of 2019 alone, there were a total of 1,788 green bond issuance deals by 496 issuers, of which the largest proportion (50%) of the issuers were private sector financial and non-financial firms. Between 2018 and 2019, global private sector firms issued green bonds worth of $110 billion, while European investment banks and Chinese banks were reportedly more active issuers more recently.4) Green bonds issued in 2019 were invested in new and renewable energy (31%), green infrastructure (30%), green mobility (20%), and water quality improvement (9%).

US investment banks have engaged in massive SRI projects as well in their move to respond to climate change, build green infrastructure, and shift towards new and renewable energy. JP Morgan recently published a report on its environmental and social policy framework to better deal with climate change and protect the environment and ecosystems.6) In the report, the bank reaffirmed its commitment to the Paris Agreement and unveiled its plans to give financial support via SRI to sectors that are working on cutting greenhouse gas emissions and switching to new and renewable energy. Also, it pledged to stop financing firms related to fossil fuel burning, deforestation, Arctic development, and other environmental degradation. At the end of 2019, Goldman Sachs also unveiled a plan to invest $750 billion in climate-friendly projects for the next ten years. In its recently released report on the green economy, it projected that clean tech would facilitate new investments worth of $1 trillion–$2 trillion and create 1,500–2,000 new jobs, leading economic recovery and sustainable growth in the post-Covid-19 era.7) Other players such as Bank of America and Citigroup have also unveiled environment and sustainable reports to announce their initiatives to increase their loan and investment for cutting greenhouse gas emissions, building green infrastructure, and shifting towards new and renewable energy.

Overseas cases in response to the Green New Deal

The EU has implemented the carbon emission rights trading scheme since 2005 as part of its emission-cutting effort.8) As of 2020, around 40 countries already launched or plan to launch the emissions trading scheme, which will expand to more emerging economies such as China as recommended by the 2015 Paris Agreement. In 2019 alone, carbon emissions of 14.5 billion tons were traded on the EU Emission Trading System (EU ETS), which is a 4.6-fold increase from 3.1 billion tons in 2013.9) During the same period, prices of emission allowances in Europe jumped 7.4-fold to EUR 25 from EUR 3.4. What’s notable in Europe’s carbon dioxide emission allowances is the vigorous trading not only in the spot market, but also in the derivatives market. Futures and options on emission allowances in Europe are traded actively on exchanges such as the ICE, with their trading value reaching 12-fold of the spot market as of 2019. Korea’s emission trading market has been in operation by the Korea Exchange since 2015. Since reaching 1.24 million tons in the first year of 2015, the market’s trading volume steadily rose to 16.95 million tons in 2019. It’s too bad that derivatives on emission rights do not take fully hold in Korea, which leads to illiquid emission trading with high price volatility.

Global financial firms and stock index operators are equipped with a system that assesses firms’ effort to respond to climate change, expand green infrastructure, and shift towards new and renewable energy, based on which a Green New Deal index can be systematically computed. Global leading operators such as MSCI and S&P Global have already unveiled a separate climate transition index, while asset managers such as Lyxor launched ETFs on climate change indices. And those products have thus far performed well. Furthermore, those index operators and global IBs assess firms’ effort to tackle climate change and to switch to new and renewable energy, for reflecting the results into the environment category of ESG scores.

Challenges ahead of Green New Deal

Governments in Europe and major developed economies such as the US have already established concrete goals and invested massive funds in projects related to climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition that are expected to help the globe to weather the social and economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and to achieve sustainable growth. More recently, the Korean government also unveiled plans to invest a total of KRW 73.4 trillion in the Green New Deal projects for the next five years, which is expected to create 659,000 jobs. It would have been much better if Korea’s financial services and investment companies have shown keen interest in the issues such as climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition, or if they have invested largely in green projects. According to the Climate Change Performance Index of 2019 compiled by GARP to measure how economies around the globe are responding to climate change, European countries ranked high while Korea ranked lower at 58th, clearly lagging behind in this issue. Korea’s financial services and investment industry should invest more of their human and physical capital in the Green New Deal because doing so fits well for the industry’s stated mission to help firms raise risk capital and achieve sustainable growth of private sector firms.

Based on what’s discussed thus far, I propose some of the challenges ahead of Korea’s capital markets towards the success of Korea’s Green New Deal. First, financial services firms need to take note of the cases of global investment banks for devising their mid- to long-term business objectives that include concrete goals regarding climate change, green infrastructure, and renewable energy transition. A strategy worth considering is to cut financing to firms that are highly likely to induce carbon emissions and destroy ecosystems. Second, issuing and underwriting green bonds need to take fully hold so that more investments flow to green projects for emission reduction, urban regeneration, renewable energy transition, etc. It’s worth considering the public sector providing guarantees when a private sector financial services firm participates in a high-risk, carbon-friendly project. Third, also necessary includes an index linked to climate change responses and renewable energy transition, and ETFs and other related financial investment products. It’s also advisable to include green infrastructure in REITS assets, which is expected to facilitate publicly-offered financial investment products related to the Green New Deal. Fourth, a research report, or any system that assesses the environmental factors in ESC scores on a regular basis could encourage Korean firms to pay more attention to key climate change issues. Fifth, listing and trading of derivatives on carbon emission rights will surely help effectively reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stabilize the emission trading market.

1) Refer to https://www.gov.uk/government.

2) Ministry of Environment, October 22, 2019, Second basic plan for climate change response, Press Release.

3) Ministry of Economy and Finance, July 14, 2020, Government announces overview of Korean New Deal, Press Release.

4) As of 2019, the largest issuer of green bonds was Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, followed by China’s Industrial Bank, Crédit Agricole, and BNP Paribas.

5) FT News, July 2020, Lagarde Puts Green Policy Top of Agenda in ECB Bond Buying.

6) JP Morgan, February 2020, Environment and social policy framework.

7) Goldman Sachs, 2020. 6, Carbonomics: The green engine of economic recovery.

8) Refer to Key Issues in Global Emission Trading Market in 2018 (Ministry of Environment, 2019).

9) https://icapcarbonaction.com