OPINION

2020 Sep/15

A Necessary Overhaul of Korea’s Debt Collection Market and Policy Challenges

Sep. 15, 2020

PDF

Park, Chang Gyun

- Summary

- Korea announced a plan to legislate the Consumer Credit Act with an aim to help individual borrowers to quickly recover bad debts and return to normal economic activities, and to regulate harsh debt collection practices. The proposed law is expected to effectively fill the regulatory gap in the area where market failure is highly likely. However, there’re also warnings about a possibility that an excessive government intervention in the debt collection market could undermine Korea’s credit culture. A desirable regulatory framework on the debt collection market should be designed to minimize social costs arising from excessive debt collection, but not to rein in debt collection too harshly to cause moral hazard among debtors. Although there will be numerous talks during the legislative process, two issues in particular need in-depth discussions. First, it’s necessary to allow the proposed debt relief negotiator to step in before overdue for offering credit counseling such as financial education and advice on personal finance. Second, a more desirable regulatory principle than a mandate-only approach should be market discipline that encourages players to do better for their reputation risk. Towards that end, it’s advisable to bolster accountability of original creditors, and to allow outsourced debt collectors to enter the debt buyer market.

1. Introduction

In October 2019, Korea’s Financial Services Commission unveiled its plans to legislate the Consumer Credit Act (tentatively named), seeking to regulate excessive debt collection activities of debt collectors and to help more individual (non-business) debtors to return to normal economic activities via a faster debt relief process. There have been persistent reports that harsh debt collection spanning for a long period hinders debtors from engaging in normal economic activities. In response, Korea has made success by establishing a regulatory basis with several legislations, for example, the 2009 Fair Debt Collection Practices Act that set forth general principles on regulating debt collection activities; the 2006 Debtor Rehabilitation and Bankruptcy Act; and the 2016 Microfinance Support Act that paved the way for public and private sector procedures for settling individual debts that went sour. From the perspective of market discipline, however, it’s admittable that the current regulatory scheme has been fragmented and on a one-off basis, dealing with one problem after another without a more holistic regulatory framework. What’s encouraging about the proposed Consumer Credit Act is that the new law could offer a ground for filling the regulatory gap in the area where market failure is highly probable. However, a formidable number of opinion leaders have voiced their warnings. They argue that, as debt collection in nature is not just a tool for serving creditor’s interest but more importantly a tool for preventing debtors’ moral hazard, an excessive government intervention in the debt collection market has a danger of seriously undermining Korea’s credit culture that has been relatively in good shape. A desirable regulatory framework on the debt collection market should be designed to minimize social costs arising from excessive debt collection, and to try not to regulate it too harshly to cause moral hazard among debtors.

This article explores the structure of the debt collection market and the need for regulation, from which to derive some meaningful issues that should be taken into account during the legislation of the Consumer Credit Act.

2. Structure of the debt collection market

A financial firm that offered credit loans to its personal client usually tries to take several measures if the debtor fails to repay the principal and interest payments on schedule so the debt gets overdue. One of the typical procedures in this case is that the creditor notifies the debtor of the overdue by phone or mail, and requests payments. If this doesn’t work, the creditor may go for asset investigation, and, if any asset is found, seek compulsory execution under a court order. Such a debt collection procedure is sometimes directly handled by the creditor financial firm, but mostly outsourced to firms labelled as credit information companies (outsourced debt collectors, hereinafter). If the overdue debt is not serviced for a certain period of time, then the creditor financial firm notifies the debtor of the event of default.1) In that case, the creditor demands the debtor to pay the whole amount of the unpaid principal and interest. Once an event of default is declared, the loan is subject to a higher interest rate, so-called the overdue interest rate. If the debt is still not serviced for a substantial period of time after the event of default,2) the creditor financial firm would write it off from the financial statements, and transfer it to an off-balance account. Most written-off debts are purchased by debt buyers who then become a new creditor to exercise all rights, including collecting claims. Korea’s law allows credit service providers to engage in the debt buyer business as a sideline once they meet certain statutory requirements and register themselves with the relevant authority. If the debts are not serviced despite collection efforts, they are again sold to another debt buyer.

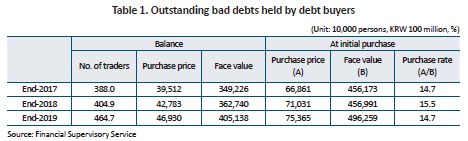

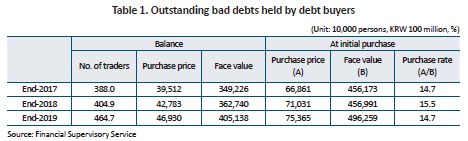

In Korea’s debt collection market, there is a hierarchical relationship where original creditor financial firms supply new bad debts for outsourced debt collectors and debt buyers. As of end-2019, there are 22 outsourced debt collectors in operation,3) most of which are a wholly owned subsidiary of a financial firm. According to the Financial Supervisory Service, financial firms outsourced the collection of new debts worth of KRW 76.5 trillion to outsourced debt collectors in 2019 alone. Moreover, it is reported that as of end-2019 a total of 984 debt buyers were registered and in operation with their bad debt holdings of KRW 40.5 trillion by measure of the principal.

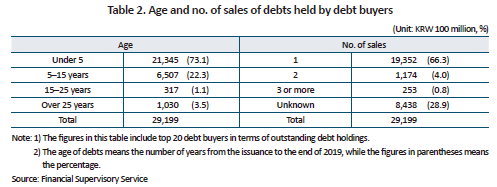

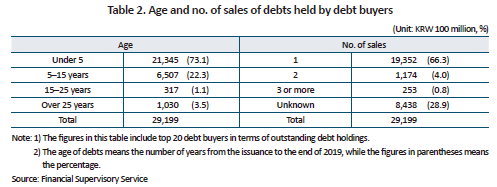

Banks, savings banks, and credit financial institutions, credit service providers, and other financial firms acting as lenders are known to sell bad debts in the debt buyer market. Among them, credit service providers account for the largest portion, followed by savings banks (26.6%) and credit financial institutions (22.3%). Such a high proportion of credit service providers stems from the fact that they often sell debt buyers the bad debts that they bought from financial institutions but failed to collect for a certain period of time. About 22.3% of debts held by debt buyers are 5–15 years old, and it’s hard to trace how many times debts in another 28.9% changed hands, which suggests the long-term nature of bad debt collection.

3. Needs for regulating the debt collection market

The market for collecting bad debts held by individuals is well known for excessive debt collection practices and the side effects. The persistent tightening of the debt collection regulation failed to put an end to illicit practices, for example, a collector may harass debtors by repeatedly visiting their work and home, notify the debt status to third parties, or do any mental or physical harm. Although some of them are not unlawful, current debt collection practices need pondering over to ensure that they don’t undermine human rights of debtors or social welfare on the whole.

Government regulation on the market can be justified by market failure. Currently, the debt collection market has three factors giving rise to market failure. First, creditors’ market dominance arising from different bargaining power between creditor and debtors could possibly lead to a practice of excessive debt collection. Under general practices of the market for debts to individual debtors, a contract is established when a creditor determines terms and conditions of a debt including matters related to debt collection, notifies those to a debtor, and asks whether the debtor accepts them or not. The debtor with weaker bargaining power usually has no option but to agree with them whether they like them or not. Under the agreement, they are forced to bear excessive debt collection practices. Another issue is about adverse selection. Without accurate information on how tolerable individual debtors are towards levels of debt collection, a creditor may propose a debt contract with the average interest rate under the assumption of average tolerance. In this case, the creditor is likely to suffer losses due to higher-than-expected default events, and thus may try to avoid losses by charging higher interest rates. As is well known, a higher interest rate than before could backfire because it drives out customers with lower credit risk and leaves the creditor with only those with higher credit risk. In response to the possibility of such losses, creditors could come up with tougher debt contracts including harsh debt collection. Because other creditors share the same incentive, the market in the end will reach an equilibrium where all creditors are willing to lend only under the condition of ruthless debt collection. That adverse selection leads to debt collection practices that go way beyond socially acceptable levels. Last, there are calls for public regulation over the debt collection market that is expected to address debtors’ lack of experience or irrational decisions from the perspective of behavioral economics recently in the limelight. Unlike creditors who have proven experience and expertise in credit transactions as a result of repetitive trading, debtors who lack experience and expertise in dealing with intricate information may wrongly end up with signing on a debt contract full of unfavorable terms and conditions. A debt contract includes a variety of information, but only some of them manage to catch debtors’ attention. Information regarding the interest rate and maturity of a debt falls under salient information, while non-salient information includes matters related to debt collection. If not content with salient information, debtors tend to get back to creditors for further negotiation or to find a third-party creditor for a new contract. More often than not, however, they overlook non-salient information. It’s possible for such a tendency to undesirably help make debt collection provisions in favor of creditors only.

4. Legislation of the Consumer Credit Act and challenges ahead

According to the report in February, the proposed Consumer Credit Act currently under legislative process contains the followings: 1) Granting delinquent debtors who experienced a decline in repayment ability a right to request new debt conditions to the creditor financial firm, which is supported by the introduction of the debt relief negotiation business; 2) reducing the increasing burden on debtors during the period of overdue; 3) reining in excessive debt collection practices of debt collectors; and 4) structural reform aiming to eliminate the incentive for harsh debt collection.

The proposed debt relief negotiation business refers to services provided to help debtors have stronger bargaining power when exercising their debt relief right, which could be likened to credit counselors in many countries including the US and the UK. However, unlike credit counselors who provide a wide range of advice and counseling on personal finance, the scope of the proposed business seems to be limited to debt relief process for delinquent debtors only, which could possibly undermine expected outcomes of the credit counselor scheme. A credit counselor is a consumer finance expert that provides assistance and advice on rational consumer financial activities via various services such as financial education, counseling, and debt management. In particular, debt management means a service for a debtor who is or on the verge of becoming delinquent due to excessive debt burden. For such a debtor, a debt management service provider offers a diagnosis of financial conditions and relevant advice, and, if necessary, negotiates for debt relief on behalf of the debtor. In short, the role played by credit counselors is more broad-based, compared to the debt relief negotiation business that negotiates for debt relief on behalf of a delinquent debtor only. Given that bad debts held by individual debtors usually become even more distressed and harder to recover as time goes by, it’s worth considering allowing the debt relief negotiation business to step in before overdue.

Aiming to eliminate the incentive for excessive debt collection practices, policy authorities’ structural reform proposes to lower the leverage cap of debt buyers and to ban them from running the credit service business as a sideline. Although they appear to head in the right policy direction in principle, a desirable regulatory framework should also take into account the fact that regulatory tightening for the sake of protecting debtors always comes with costs. Of course this is a matter of degree, but it’s not deniable that regulatory tightening leads to a higher incentive for debtors’ moral hazard. Credit financial firms’ voicing such concerns cannot be dismissed as overtly fueling a sense of crisis. Furthermore, a great number of empirical results confirm that a tightening of debt collection regulation pushes up interest rates and makes it harder for those with low income and bad credit to tap into credit. Taking into account the costs associated with regulation, the basic principle should be to prioritize market discipline, rather than overly depending on mandates. More concretely, market discipline intends to predispose creditors and debt collectors to be more concerned about their reputational risk and to refrain from excessive debt collection practices, which has critical implications for the market. Admittedly, it’s hard to control debt buyers using reputational risk because most of them are small-sized. It’s worth considering bringing in larger players who concern more about their own reputational risk, for example, credit information companies. What’s necessary ahead of others is to allow credit information companies to enter the debt buyer market, which enables market discipline to work to effectively prevent excessive debt collection practices. Although some degree of regulatory tightening is inevitable for protecting debtors, it’s desirable to minimize mandates on debt buyers and instead to focus on market discipline by financial firms more concerned about their reputational risk, as is the case for London. In London, the Credit Services Association—a trade union for businesses holding a debt collecting license—established the Code of Practice, based on which to self-regulate its members. Aiming to induce financial firms—original creditors—to willingly prevent excessive debt collection practices, the supervisory authority mandates those financial firms to sell debts or to outsource debt collection to only those who officially endorse the Code.

1) This is also called the event of the ‘loss of benefit of time’, where the benefit of time refers to a debtor’s right not to be demanded to make repayment in advance of the due date or exceeding the amount in the loan schedule. For bank credit loans, an event of default is usually declared 30 days after overdue.

2) Although varying across creditors, banks usually write off debts one year after overdue. To prevent bad debts from deteriorating overall financial health, lenders classify their debts into several categories (special mention, substandard, doubtful, etc.) depending on the overdue period and the estimated collectible amount even before one year, and keep bad debt reserves.

3) The figure excludes one credit rating agency and three collectors whose operation is only for internal purposes (http://fine.fss.or.kr/main/fin_comp/fincomp_inqui/comsearch01list.jsp).

In October 2019, Korea’s Financial Services Commission unveiled its plans to legislate the Consumer Credit Act (tentatively named), seeking to regulate excessive debt collection activities of debt collectors and to help more individual (non-business) debtors to return to normal economic activities via a faster debt relief process. There have been persistent reports that harsh debt collection spanning for a long period hinders debtors from engaging in normal economic activities. In response, Korea has made success by establishing a regulatory basis with several legislations, for example, the 2009 Fair Debt Collection Practices Act that set forth general principles on regulating debt collection activities; the 2006 Debtor Rehabilitation and Bankruptcy Act; and the 2016 Microfinance Support Act that paved the way for public and private sector procedures for settling individual debts that went sour. From the perspective of market discipline, however, it’s admittable that the current regulatory scheme has been fragmented and on a one-off basis, dealing with one problem after another without a more holistic regulatory framework. What’s encouraging about the proposed Consumer Credit Act is that the new law could offer a ground for filling the regulatory gap in the area where market failure is highly probable. However, a formidable number of opinion leaders have voiced their warnings. They argue that, as debt collection in nature is not just a tool for serving creditor’s interest but more importantly a tool for preventing debtors’ moral hazard, an excessive government intervention in the debt collection market has a danger of seriously undermining Korea’s credit culture that has been relatively in good shape. A desirable regulatory framework on the debt collection market should be designed to minimize social costs arising from excessive debt collection, and to try not to regulate it too harshly to cause moral hazard among debtors.

This article explores the structure of the debt collection market and the need for regulation, from which to derive some meaningful issues that should be taken into account during the legislation of the Consumer Credit Act.

2. Structure of the debt collection market

A financial firm that offered credit loans to its personal client usually tries to take several measures if the debtor fails to repay the principal and interest payments on schedule so the debt gets overdue. One of the typical procedures in this case is that the creditor notifies the debtor of the overdue by phone or mail, and requests payments. If this doesn’t work, the creditor may go for asset investigation, and, if any asset is found, seek compulsory execution under a court order. Such a debt collection procedure is sometimes directly handled by the creditor financial firm, but mostly outsourced to firms labelled as credit information companies (outsourced debt collectors, hereinafter). If the overdue debt is not serviced for a certain period of time, then the creditor financial firm notifies the debtor of the event of default.1) In that case, the creditor demands the debtor to pay the whole amount of the unpaid principal and interest. Once an event of default is declared, the loan is subject to a higher interest rate, so-called the overdue interest rate. If the debt is still not serviced for a substantial period of time after the event of default,2) the creditor financial firm would write it off from the financial statements, and transfer it to an off-balance account. Most written-off debts are purchased by debt buyers who then become a new creditor to exercise all rights, including collecting claims. Korea’s law allows credit service providers to engage in the debt buyer business as a sideline once they meet certain statutory requirements and register themselves with the relevant authority. If the debts are not serviced despite collection efforts, they are again sold to another debt buyer.

In Korea’s debt collection market, there is a hierarchical relationship where original creditor financial firms supply new bad debts for outsourced debt collectors and debt buyers. As of end-2019, there are 22 outsourced debt collectors in operation,3) most of which are a wholly owned subsidiary of a financial firm. According to the Financial Supervisory Service, financial firms outsourced the collection of new debts worth of KRW 76.5 trillion to outsourced debt collectors in 2019 alone. Moreover, it is reported that as of end-2019 a total of 984 debt buyers were registered and in operation with their bad debt holdings of KRW 40.5 trillion by measure of the principal.

The market for collecting bad debts held by individuals is well known for excessive debt collection practices and the side effects. The persistent tightening of the debt collection regulation failed to put an end to illicit practices, for example, a collector may harass debtors by repeatedly visiting their work and home, notify the debt status to third parties, or do any mental or physical harm. Although some of them are not unlawful, current debt collection practices need pondering over to ensure that they don’t undermine human rights of debtors or social welfare on the whole.

Government regulation on the market can be justified by market failure. Currently, the debt collection market has three factors giving rise to market failure. First, creditors’ market dominance arising from different bargaining power between creditor and debtors could possibly lead to a practice of excessive debt collection. Under general practices of the market for debts to individual debtors, a contract is established when a creditor determines terms and conditions of a debt including matters related to debt collection, notifies those to a debtor, and asks whether the debtor accepts them or not. The debtor with weaker bargaining power usually has no option but to agree with them whether they like them or not. Under the agreement, they are forced to bear excessive debt collection practices. Another issue is about adverse selection. Without accurate information on how tolerable individual debtors are towards levels of debt collection, a creditor may propose a debt contract with the average interest rate under the assumption of average tolerance. In this case, the creditor is likely to suffer losses due to higher-than-expected default events, and thus may try to avoid losses by charging higher interest rates. As is well known, a higher interest rate than before could backfire because it drives out customers with lower credit risk and leaves the creditor with only those with higher credit risk. In response to the possibility of such losses, creditors could come up with tougher debt contracts including harsh debt collection. Because other creditors share the same incentive, the market in the end will reach an equilibrium where all creditors are willing to lend only under the condition of ruthless debt collection. That adverse selection leads to debt collection practices that go way beyond socially acceptable levels. Last, there are calls for public regulation over the debt collection market that is expected to address debtors’ lack of experience or irrational decisions from the perspective of behavioral economics recently in the limelight. Unlike creditors who have proven experience and expertise in credit transactions as a result of repetitive trading, debtors who lack experience and expertise in dealing with intricate information may wrongly end up with signing on a debt contract full of unfavorable terms and conditions. A debt contract includes a variety of information, but only some of them manage to catch debtors’ attention. Information regarding the interest rate and maturity of a debt falls under salient information, while non-salient information includes matters related to debt collection. If not content with salient information, debtors tend to get back to creditors for further negotiation or to find a third-party creditor for a new contract. More often than not, however, they overlook non-salient information. It’s possible for such a tendency to undesirably help make debt collection provisions in favor of creditors only.

4. Legislation of the Consumer Credit Act and challenges ahead

According to the report in February, the proposed Consumer Credit Act currently under legislative process contains the followings: 1) Granting delinquent debtors who experienced a decline in repayment ability a right to request new debt conditions to the creditor financial firm, which is supported by the introduction of the debt relief negotiation business; 2) reducing the increasing burden on debtors during the period of overdue; 3) reining in excessive debt collection practices of debt collectors; and 4) structural reform aiming to eliminate the incentive for harsh debt collection.

The proposed debt relief negotiation business refers to services provided to help debtors have stronger bargaining power when exercising their debt relief right, which could be likened to credit counselors in many countries including the US and the UK. However, unlike credit counselors who provide a wide range of advice and counseling on personal finance, the scope of the proposed business seems to be limited to debt relief process for delinquent debtors only, which could possibly undermine expected outcomes of the credit counselor scheme. A credit counselor is a consumer finance expert that provides assistance and advice on rational consumer financial activities via various services such as financial education, counseling, and debt management. In particular, debt management means a service for a debtor who is or on the verge of becoming delinquent due to excessive debt burden. For such a debtor, a debt management service provider offers a diagnosis of financial conditions and relevant advice, and, if necessary, negotiates for debt relief on behalf of the debtor. In short, the role played by credit counselors is more broad-based, compared to the debt relief negotiation business that negotiates for debt relief on behalf of a delinquent debtor only. Given that bad debts held by individual debtors usually become even more distressed and harder to recover as time goes by, it’s worth considering allowing the debt relief negotiation business to step in before overdue.

Aiming to eliminate the incentive for excessive debt collection practices, policy authorities’ structural reform proposes to lower the leverage cap of debt buyers and to ban them from running the credit service business as a sideline. Although they appear to head in the right policy direction in principle, a desirable regulatory framework should also take into account the fact that regulatory tightening for the sake of protecting debtors always comes with costs. Of course this is a matter of degree, but it’s not deniable that regulatory tightening leads to a higher incentive for debtors’ moral hazard. Credit financial firms’ voicing such concerns cannot be dismissed as overtly fueling a sense of crisis. Furthermore, a great number of empirical results confirm that a tightening of debt collection regulation pushes up interest rates and makes it harder for those with low income and bad credit to tap into credit. Taking into account the costs associated with regulation, the basic principle should be to prioritize market discipline, rather than overly depending on mandates. More concretely, market discipline intends to predispose creditors and debt collectors to be more concerned about their reputational risk and to refrain from excessive debt collection practices, which has critical implications for the market. Admittedly, it’s hard to control debt buyers using reputational risk because most of them are small-sized. It’s worth considering bringing in larger players who concern more about their own reputational risk, for example, credit information companies. What’s necessary ahead of others is to allow credit information companies to enter the debt buyer market, which enables market discipline to work to effectively prevent excessive debt collection practices. Although some degree of regulatory tightening is inevitable for protecting debtors, it’s desirable to minimize mandates on debt buyers and instead to focus on market discipline by financial firms more concerned about their reputational risk, as is the case for London. In London, the Credit Services Association—a trade union for businesses holding a debt collecting license—established the Code of Practice, based on which to self-regulate its members. Aiming to induce financial firms—original creditors—to willingly prevent excessive debt collection practices, the supervisory authority mandates those financial firms to sell debts or to outsource debt collection to only those who officially endorse the Code.

1) This is also called the event of the ‘loss of benefit of time’, where the benefit of time refers to a debtor’s right not to be demanded to make repayment in advance of the due date or exceeding the amount in the loan schedule. For bank credit loans, an event of default is usually declared 30 days after overdue.

2) Although varying across creditors, banks usually write off debts one year after overdue. To prevent bad debts from deteriorating overall financial health, lenders classify their debts into several categories (special mention, substandard, doubtful, etc.) depending on the overdue period and the estimated collectible amount even before one year, and keep bad debt reserves.

3) The figure excludes one credit rating agency and three collectors whose operation is only for internal purposes (http://fine.fss.or.kr/main/fin_comp/fincomp_inqui/comsearch01list.jsp).