OPINION

2021 Apr/07

Causes behind Rising US Long-term Interest Rates and Possible Shift in Lower for Longer

Apr. 06, 2021

PDF

- Summary

- The causes behind the sharp rise in US long-term Treasury yields this year could stem from the upward adjustment in inflation and growth projections in line with large-scale fiscal expansion. However, this round of fiscal expansion, despite its sheer scale, is largely a one-off transfer payment, which is found to have no significant impact on the nominal neutral interest rate and long-term inflation expectations. This implies market participants perceiving the recent yield change as a cyclical increase, instead of a shift in the low interest rate stance. However, Korea’s interest rate is strongly in sync with the US Treasury yields amid the looming expectation for Fed tapering. This reinforces the need for Korea’s financial investment industry to ramp up its risk management bracing for interest rate increases in the short-run, and to prepare for a possibility of the lingering low interest rate due to structural factors in the long-run.

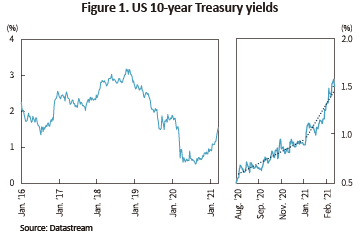

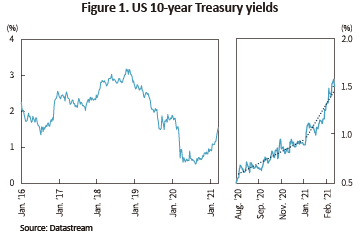

Recently, the steep rise in US long-term Treasury yields has widened volatility in the international financial markets. As shown in Figure 1, US 10-year Treasury yields climbed from 0.5% in early August 2020 to 0.9% at the end of December 2020, and to surpass 1.5% more recently. Particularly starting from this year, the pace of yield increase went up more than three-fold, and the level of yields reached as high as that of August 2019 at the peak of the US-China trade dispute. With the abrupt increase in long-term interest rates, NASDAQ kept fluctuating wildly, once plunging more than 10% from this year’s peak.

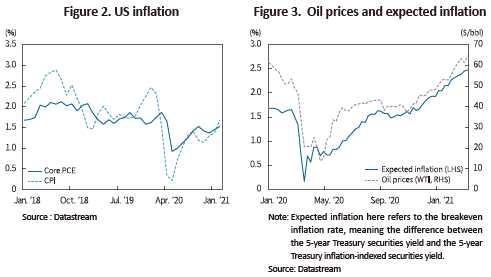

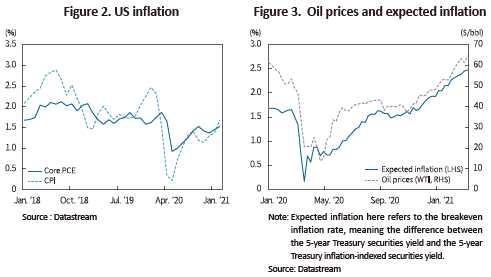

After August 2020, US long-term interest rates were in an upward trend amid signs of economic recovery. But why did they begin soaring steeply this year? One of the primary causes is concern about inflation. Although inflation is hovering around the 1% range at present, market expectations for future inflation have been rising continuously with high hopes for vaccines since early November 2020. What’s notable is that such a change in expected inflation is deeply in sync with global commodity prices such as oil prices. In terms of the supply factor, the strong increase in semiconductor prices and shipping costs is putting higher pressure on inflation. However, the steep yield increase observed recently could have stemmed from some other factors than expected inflation due to two reasons. First, expected inflation remained stable for a considerable period after Treasury yields began rebounding in August 2020. Second, even after expected inflation began climbing in November 2020, the pace of increase remained unchanged for some time.

Excluding higher expected inflation, the root cause behind the recent rise in interest rates this year could be the massive stimulus package unveiled by the Biden administration in January 2021. The American Rescue Plan as large as $1.9 trillion or 9% of 2020 GDP was unveiled on January 14 shortly after Georgia election results confirmed the democratic majority in the Senate and the House of Representatives on January 6, which fueled expectations for more issuance of government bonds, and raised concerns about higher demand-side pressure. As of November 2020, the consensus forecast for US growth in 2020 stood at 3.8%, but the Fed and major investment banks more recently raised their growth outlook to the mid 6% range or the lower 7% range. Under the assumption of 7% growth in 2021 and 4.5% in 2022, the US GDP gap will quickly move to the positive territory, which will significantly expand demand-side inflationary pressure to the mid-2000s level. Unlike expected inflation based on interest rate data, survey-based expected inflation climbed gradually during 2020, but rose sharply right after fiscal expansion materialized.

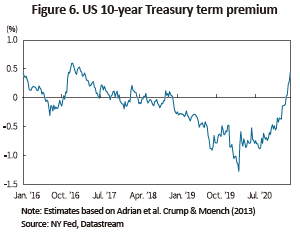

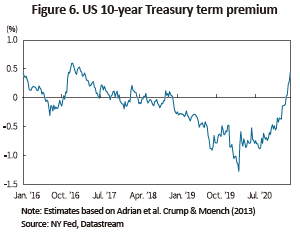

Shocks from massive fiscal expansion would not only push up growth and inflation projections, but also increase uncertainties around future growth and inflation paths. The uncertainties were particularly high not only because Democrats’ narrow Senate majority increased uncertainties around Senate deliberations on the stimulus package’s size and target but also because there exist doubts and uncertainties about the policy effect of large-scale fiscal expansion in addition to previous packages during the course of economic recovery. Meanwhile, the fast pace of economic recovery amid the projected large-scale government bond issuance to support the Biden administration’s fiscal expansion could move up the timeline of Fed tapering, which would further increase concerns about the demand of the government bond market. On top of the lingering uncertainties about long-term growth and inflation paths, the burden on demand and supply dynamics of long-term government bonds will add costs to long-term bond holding, in other words, widening term premium and pushing up government bond yields. All in all, the recent increase in government bond yields should be rightly read as a fiscal tantrum triggered by massive fiscal expansion, rather than as an inflation tantrum caused by inflationary concerns. In the same vein, the steady rise in expected inflation this year is more likely the result of fiscal expansion.

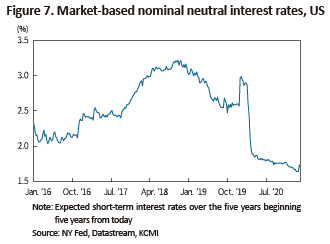

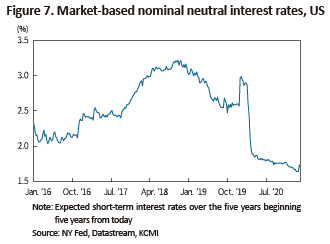

Then, will the upward trend in government bond yields change the course of the low-interest rate stance? As mentioned in why the term premium of long-term government bonds rose, there are significant uncertainties around growth and inflation paths. Although this makes any projection of government bond yields shaky, it is worth looking at the nature of fiscal expansion which caused government bond yields to climb further. The recent phenomenon is a déjà vu of what happened in 2016: Right after winning the presidential election, former President Trump adopted massive tax cuts, sending government bond yields soaring over (Figure 1). The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act1) fueled expectations for more corporate investment and higher mid- to long-term growth, which led to an increase in the nominal neutral interest rate—market-based estimates of short-term interest rates for over the five years beginning five years from today. This supported US interest rate increases until before the US-China trade conflict (Baek & Kang, 2018). On the other hand, this round of fiscal expansion is somewhat different as the nominal neutral interest rate kept hovering around the low level reached after the March 2020 decline despite expectations for steep real economic recovery and inflation.

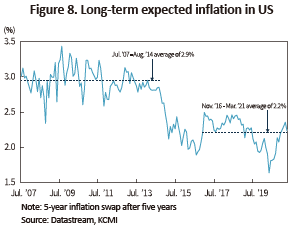

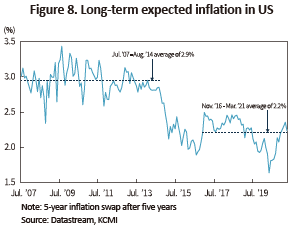

Unlike the 2017 tax cuts, this round of fiscal expansion is largely based on one-off transfer payments such as disaster relief funds, unemployment benefits,2) and other financial support to municipal governments and vaccines and virus testing, all of which expand demand only temporarily with limited impacts on boosting productivity. In the same vein, major economic research institutions predicted that the baseline effect from the low inflation in the 2020 would cause inflation to surge in 2021 before subsiding slowly. Market participants’ outlook on long-term inflation is also similar to the level reached during the 2017 expansionary cycle (see Figure 5 and Figure 8). Despite some concerns about the possibility of inflation lingering further after 2021, such a projection is supported by research: Powell (2018) argued that well-anchored inflation expectations could reduce the impact of past inflation on current inflation. Given the possibility of this round of fiscal expansion impacting inflation and growth only temporarily, the recent rise in interest rates could be viewed as a cyclical increase, rather than a trend change in the lower for longer. This is also possibly reflected in the market-based nominal neutral interest rate as well as long-term inflation expectations.

However, there are several upward risk factors in US growth and inflation in the long run, for example, Biden’s giant infrastructure plan ($2 trillion to $4 trillion during his tenure), the minimum wage hike to $15 per hour by 2025 from today’s $7.5 per hour. Although the possibility of those factors materializing seems quite low for now, there is still a slight possibility that those factors would push up potential growth and inflation expectations, driving the rise in the nominal neutral interest rate as well as government bond yields. If met with the Fed’s rate hike, this might keep the long-term interest rate hovering around the high level for a considerable period.

On another front, why is the Fed taking no additional action against the signs of financial unrest triggered by yield rises? In a speech delivered on February 23, 2021, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell described the recent yield rise as the market’s confidence in solid recovery in the real economy, ruling out the possibility of another expansionary measure. This was also echoed by other high-ranking Fed officials including Kansas City Fed President Esther George, St. Louis Fed President Jim Bullard, and Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic. Taken together, the yield rise could impose adjustment pressure on stocks and other risky assets. But as long as the size of adjustment is moderate, the Fed appears to see it as a natural process of the widened discrepancy between the financial sector and the real economy narrowing down. That is to say that the Fed is expected to decrease their support to the rising financial market volatility as the real economy is showing signs of recovery backed by massive fiscal spending and vaccination going forward.

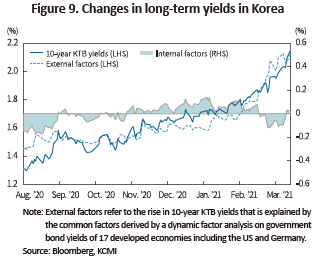

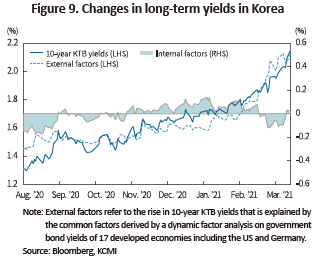

The question ahead of us would be the impacts and implications US long-term yield increases on Korea’s capital markets and the financial investment industry. Korea’s bond yields also climbed sharply during the rise in US Treasury yields, showing a strong synchronization. Just as the US expanded fiscal spending, Korea also saw several rounds of supplementary budgets being passed, and the idea of loss compensation for small business owners and the self-employed being discussed, which increased the possibility of increasing government bond supply further. An analysis decomposing the causes behind the changes in Korea’s long-term yields into internal and external factors revealed that the rise of Korea’s bond yields from November 2020 to mid-February 2021 mainly results from the internal factor, but the yields began rising steeply from mid-February 2021 to the present due to the external factor.

Accordingly, Korea’s stock market is faced with adjustment pressure due to the rising discount rate. This is especially so when the stock market’s sensitivity to interest rates is quite high after the strong rebound in the previous year amid positive expectations about the expected growth momentum in large-cap stocks related mainly to electric vehicle, batteries, non-memory semiconductors, and auto electrical parts. As the US economy is clearly recovering and another Fed loosening is hard to expect, Korea’s government bond yields are expected to move in sync with US long-term yields. Such a higher correlation between asset prices will further reinforce the necessity of risk management.

Although the US yield increase is viewed as cyclical, Korea will again face the “low for longer” issue in the long run due to structural factors such as the global trend of falling growth, population ageing, and deepened inequality after the Covid-19 outbreak. Under the context, the recent yield increase is more desirably viewed to help Korea’s capital markets and financial investment industry to buy time for bracing for the low interest rate era. The industry needs to capitalize on this as an opportunity to renew its financial investment products and asset management services fit for the low interest rate era.

1) Trump’s tax reform is estimated to have widened federal government debt by $1 trillion to $2 trillion from 2018 to 2025 (Tax Policy Center, 2020).

2) Considering the pace of economic recovery and the possibility of economic recovery resuming in the latter half of this year, it is highly likely that unemployment benefits are unlikely paid as planned.

References

Adrian, T., Crump, R., Moench, E., 2013, Pricing the term structure with linear regression, Journal of Financial Economics 110(1), 110-138.

Powell, J., 2018, Monetary Policy and Risk Management at a Time of Low Inflation and Low Unemployment, Remarks at the 60th Annual Meeting of the NABE.

Stock, J.H., Watson, M.W., 2007, Why has U.S. inflation become harder to forecast?, Journal of Money, Credit & Banking 39, 3-33.

Summers, L., 2021. 2. 5, The Biden stimulus is admirably ambitious. But it brings some big risks, too, Washington Post.

Tax Policy Center, 2020, How did the TCJA affect the federal budget outlook?, available at www.taxpolicycenter.org.

(Korean)

Baek, I.S., Kang H.J., 2018, Analysis on causes behind the recent interest rate increase in the US and Korea, and diagnosis on possible changes in the low-rate trend, KCMI Issue Report 18-04.

On another front, why is the Fed taking no additional action against the signs of financial unrest triggered by yield rises? In a speech delivered on February 23, 2021, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell described the recent yield rise as the market’s confidence in solid recovery in the real economy, ruling out the possibility of another expansionary measure. This was also echoed by other high-ranking Fed officials including Kansas City Fed President Esther George, St. Louis Fed President Jim Bullard, and Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic. Taken together, the yield rise could impose adjustment pressure on stocks and other risky assets. But as long as the size of adjustment is moderate, the Fed appears to see it as a natural process of the widened discrepancy between the financial sector and the real economy narrowing down. That is to say that the Fed is expected to decrease their support to the rising financial market volatility as the real economy is showing signs of recovery backed by massive fiscal spending and vaccination going forward.

The question ahead of us would be the impacts and implications US long-term yield increases on Korea’s capital markets and the financial investment industry. Korea’s bond yields also climbed sharply during the rise in US Treasury yields, showing a strong synchronization. Just as the US expanded fiscal spending, Korea also saw several rounds of supplementary budgets being passed, and the idea of loss compensation for small business owners and the self-employed being discussed, which increased the possibility of increasing government bond supply further. An analysis decomposing the causes behind the changes in Korea’s long-term yields into internal and external factors revealed that the rise of Korea’s bond yields from November 2020 to mid-February 2021 mainly results from the internal factor, but the yields began rising steeply from mid-February 2021 to the present due to the external factor.

Although the US yield increase is viewed as cyclical, Korea will again face the “low for longer” issue in the long run due to structural factors such as the global trend of falling growth, population ageing, and deepened inequality after the Covid-19 outbreak. Under the context, the recent yield increase is more desirably viewed to help Korea’s capital markets and financial investment industry to buy time for bracing for the low interest rate era. The industry needs to capitalize on this as an opportunity to renew its financial investment products and asset management services fit for the low interest rate era.

1) Trump’s tax reform is estimated to have widened federal government debt by $1 trillion to $2 trillion from 2018 to 2025 (Tax Policy Center, 2020).

2) Considering the pace of economic recovery and the possibility of economic recovery resuming in the latter half of this year, it is highly likely that unemployment benefits are unlikely paid as planned.

References

Adrian, T., Crump, R., Moench, E., 2013, Pricing the term structure with linear regression, Journal of Financial Economics 110(1), 110-138.

Powell, J., 2018, Monetary Policy and Risk Management at a Time of Low Inflation and Low Unemployment, Remarks at the 60th Annual Meeting of the NABE.

Stock, J.H., Watson, M.W., 2007, Why has U.S. inflation become harder to forecast?, Journal of Money, Credit & Banking 39, 3-33.

Summers, L., 2021. 2. 5, The Biden stimulus is admirably ambitious. But it brings some big risks, too, Washington Post.

Tax Policy Center, 2020, How did the TCJA affect the federal budget outlook?, available at www.taxpolicycenter.org.

(Korean)

Baek, I.S., Kang H.J., 2018, Analysis on causes behind the recent interest rate increase in the US and Korea, and diagnosis on possible changes in the low-rate trend, KCMI Issue Report 18-04.