OPINION

2021 Oct/26

The Recent Increase in Household Debt: Characteristics, Effects and Implications

Oct. 26, 2021

PDF

- Summary

- Amid loose financial conditions since the Covid-19 pandemic, household debt is rapidly increasing compared to household income. Increased household liquidity driven by high household indebtedness has heavily flowed into asset markets including real estate and stocks. In particular, with prolonged low interest rates, households are aggressively utilizing borrowings. Given negative effects of high household indebtedness on private consumption in the medium term, it is assumed that sluggish consumption including lower consumption propensity has already been underway. If household debt accumulation keeps undermining consumption in the private sector, it would exacerbate the economy’s vulnerability to shocks while eroding aggregate demand, which could weaken growth potential.

With active policy measures by the Bank of Korea and the Korean government, household debt is expected to climb at a slower pace going forward. However, thorough monitoring is needed to ensure that higher debt servicing pressures arising from rate hikes would not lead to a rise in credit risk. In particular, the government needs to provide well-targeted fiscal support to prevent credit risks from further affecting the whole economy. Since shifts of monetary policy stances may result in high volatility in asset prices, more attention should be paid to risk factors that changes in economic conditions could pose.

In response to an economic contraction after the Covid-19 shock, the Bank of Korea and the Korean government have substantially eased financial conditions with base rate cuts and market stabilization measures. With considerably low volatility in the financial market, the real economy has continued a trend of recovery after the contraction during the first half of 2020.

In the meantime, the private debt has been growing faster compared to the level of economic activities amid eased financial conditions. In particular, a sharp increase in household debt has heightened concerns over financial imbalances. In this regard, the Bank of Korea raised its benchmark interest rate in August 2021, and the financial authorities are actively dealing with excessive household debt. This article intends to take a look at characteristics of rising household debt after the pandemic outbreak, and to examine its effects and implications on the macroeconomy.

Characteristics of the recent increase in household debt

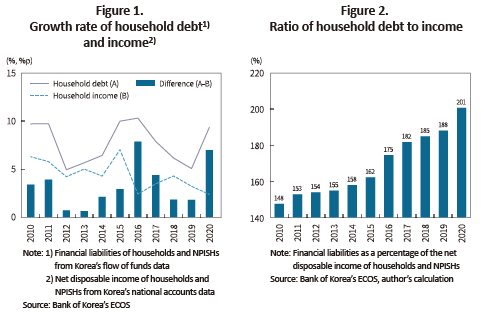

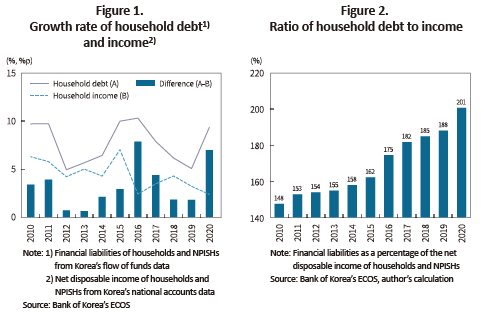

With loose financial conditions, the pace of growth in household debt has accelerated since 2020. While household income edged up 2.3% in 2020, household debt increased 9.2%, widening the disparity between income and debt growth. (Figure 1).1) Moreover, household debt jumped at a more rapid pace in the first half of 2021 to post a YoY increase of 11.3% as of the end of June.

With a steep rise in household debt relative to the real economy, the household debt-to-income ratio soared to 201% in 2020 (Figure 2). Given that the household income increased thanks to transfer incomes from the government, the pace of increase in household debt seems too fast. The net current transfer income of the household sector2) swelled to KRW 68 trillion in 2020 from KRW 31 trillion in 2019. The 2020 household income excluding current transfers, taxes, etc. (net primary income) is the same as the 2019 level of KRW 1,033 trillion. Were it not for the transfer income, the household debt-to-income ratio would have been 208%.

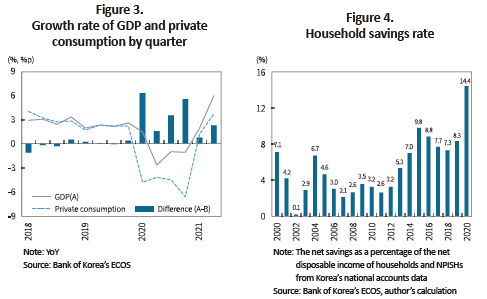

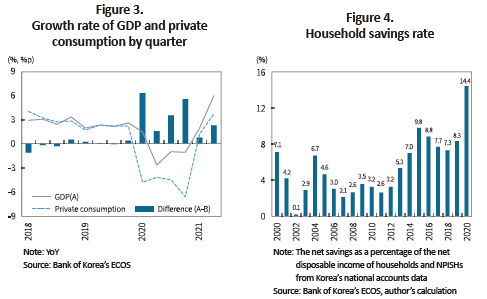

As increased household liquidity backed by high household indebtedness has rarely boosted consumption, the rising debt has limited effects on the real economy. On the contrary, lower consumption growth compared to income has persisted, thereby pushing up household savings (Figure 3, Figure 4).3) With social distancing measures in place curbing consumption, growth in private sector consumption has consistently hovered below the economic growth rate since 2020. As a result, the household savings rate jumped to 14.4% in 2020 from 8.3% in 2019.

Compared to the pre-pandemic level, higher household savings are likely to continue well into 2021. Although private consumption showed signs of recovery in the first half of 2021 with a YoY increase of 2.4%, it remains below the GDP growth rate of 4.0%. The household savings rate is expected to exceed the pre-pandemic level on the back of payment of the 5th-round disaster relief funds from the government while restrictions on economic activity due to the resurgence of the Covid-19 hinder consumption.

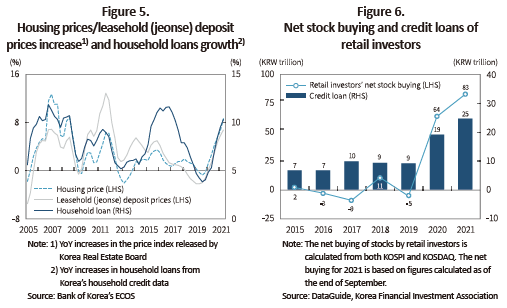

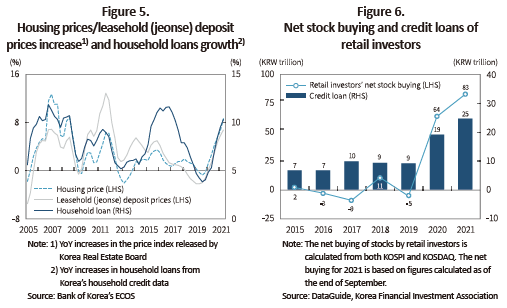

With an increase in savings, households’ funds have heavily flowed into asset markets for real estate property, stocks, etc.4) Particularly, fostered by the prolonged low interest rate environment, households are taking advantage of borrowings. Amid higher growth of household loans from 2020, housing prices and leasehold (jeonse) deposit prices, both of which are in sync with household loans, have shown an upward trend (Figure 5).5) Rising household loans have driven up housing prices, thereby expanding demand for loans for the leasehold (jeonse) deposit. Such high demand, in turn, has led to growth in household loans again, which exacerbates the volatility of both household loans and housing prices.

Meanwhile, the household net buying trend in the stock market has continued (Figure 6). The net buying of stocks by retail investors reached KRW 63.8 trillion in 2020, far surpassing the pre-pandemic level, then further climbed to KRW 83.3 trillion during the period from January to September 2021. As leverage including credit loans has surged since 2020, a growing number of investors are showing stronger risk appetite.

The effect of rising household debt on the macroeconomy

A steep increase in household debt is raising macroprudential concerns. In the wake of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, major economies like the US and the UK have seen a downward adjustment in the household debt-to-income ratio through deleveraging, whereas such a decline has not been observed in Korea since 2005 as growth of household debt has steadily exceeded that of income.

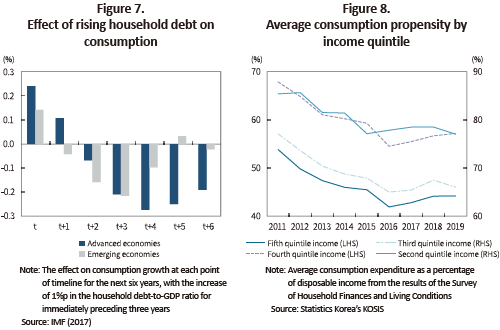

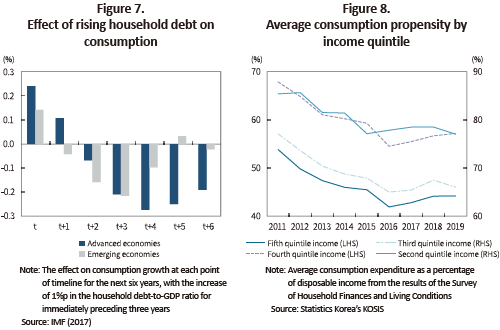

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) issued a warning that high household indebtedness would pose a serious potential risk to the macroeconomy based on its 2017 panel analysis on household debt by country. While an increase in household debt could stimulate consumption in the short term, the debt has negative effects in the medium term (Figure 7). In advanced countries where household debt ratios are higher than emerging economies, household indebtedness has a stronger effect of dampening consumption.6)

The results of the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions demonstrate that a slowdown in household consumption has been underway over the last decade (Figure 8). Households’ average propensity to consume has declined across income quintiles overall since 2011.7) The 2019 average consumption propensity of the second to fifth income quintiles is lower than the 2011 level by 8 to 11 percentage points, indicating that demand in the private sector has diminished.

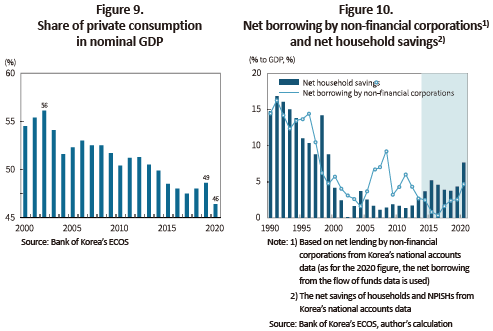

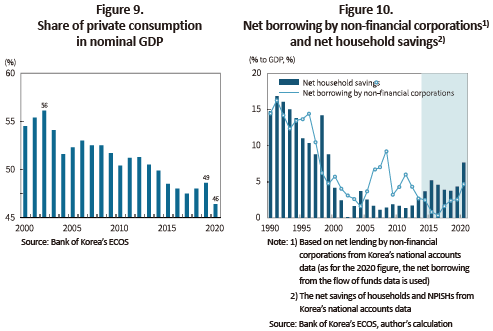

Under the circumstances, the share of private consumption in Korea’s economy has been on a steady decline (Figure 9). Except for 2020 when the economy was hit hard by the Covid-19, the private consumption as a percentage of GDP has dwindled to 48.6% in 2019 from 56.1% in 2002, showing a lingering downward trend. As the possibility of further expanding the private sector demand is limited, internal or external economic shocks could make Korea’s economy more vulnerable at a rapid pace.

Meanwhile, the flow of household savings into the real economy has weakened since the mid-2010s as companies’ funding shortfall has decreased.8) Companies utilize internal funding to make investments and if their internal funds are insufficient, they borrow from other economic agents. The net borrowing by non-financial firms surpassed the household savings level overall up until the early 2010s (Figure 10). Being used by firms for investments, household savings were channeled to the real economy. Since 2014, however, the net borrowing by firms has fallen far short of household savings, mainly due to internal funding growth and investment slowdown.9) As a result, the household savings have not been effectively provided to the real economy, which could undermine growth potential going forward.

Policy implications

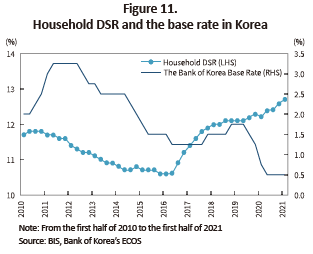

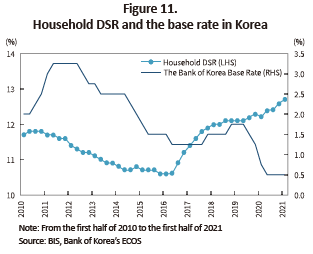

The Bank of Korea and the Korean government are actively dealing with household indebtedness with a base rate hike and management of the aggregate household debt. With these policy measures in place, the growth trend of household debt is expected to show signs of abating down the road. However, it is noteworthy that household DSR (Debt Service Ratio)—the ratio of debt service payment to income—has been on a steady rise since 2016 (Figure 11). In this regard, thorough monitoring is needed to make sure that higher debt servicing pressures driven by rate hikes would not lead to a rise in credit risk. Rising interest rates would have repercussions for the whole economy, while vulnerable groups including the self-employed workers would bear the brunt of economic activity restrictions caused by the Covid-19. Under these circumstances, the government needs to provide well-targeted fiscal support to prevent credit risks from further spreading to the economy.

A strong rebound in the global economy has sparked concerns about inflation. Some advanced countries including Korea raised interest rates in the post-pandemic cycle, and major economies would see a shift in their monetary policies.10) Given that the increase in asset prices since the onset of the pandemic has been attributed to monetary easing by central banks around the world, a potential change in monetary policies could intensify volatility in asset prices. More attention should be paid to changes in economic conditions at home and abroad, whereas households need to reassess how much investment risk they are willing to take.

1) In this article, the net disposable income and the financial liabilities of households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISHs) are used as household income and household debt, respectively.

2) This is based on the net current transfer income (excluding insurance premiums and insurance claims) of households and NPISHs from Korea’s national accounts data. Over the past decade (from 2010 to 2019), this figure stayed around its annual average of KRW 31 trillion with little change.

3) A cautious approach is needed as household income and consumption are analyzed based on aggregate indices, not taking account of different economic conditions by income bracket.

4) However, it needs to be noted that the self-employed workers who have been hit hard by the Covid-19 shock have also raised funds through household loans. As of the end of March 2021, 35.0% of the loans taken out by self-employed borrowers (KRW 831.8 trillion) are included in household loans (Bank of Korea, 2021).

5) A panel analysis on 27 countries reveals that rising household debt pushes up housing prices, which further increases household debt again (IMF, 2017).

6) In this analysis, Korea is classified as advanced economies.

7) As for the first quintile income, the average consumption propensity is exceeding 100% with the consumption level surpassing the disposable income (households living in the red).

8) The fund shortages in this article refer to the net amount non-financial corporations borrow from other economic agents including households, rather than the total amount of borrowing.

9) In the 2000s, internal funding of non-financial firms increased to meet the demand for investment funds while the growth of investment slowed down after 2011 (Cho, S.H., 2018).

10) The Bank of Korea raised its base rate in August 2021 (from 0.5% to 0.75%), followed by interest rate hikes by the central bank of Norway (from 0.0% to 0.25%) in September and by Reserve Bank of New Zealand (from 0.25% to 0.5%) in October. Moreover, there is a growing possibility that the US Fed would begin tapering within this year.

References

Bank of Korea, 2021, Financial Stability Report: June 2021.

IMF, 2017, Household debt and financial stability. In Global Financial Stability Report (October), Chapter 2.

(Korean)

Cho, S.H., 2018, Investment and fundraising of Korea’s companies: changes and implications, Capital Market Focus 2018-21.

In the meantime, the private debt has been growing faster compared to the level of economic activities amid eased financial conditions. In particular, a sharp increase in household debt has heightened concerns over financial imbalances. In this regard, the Bank of Korea raised its benchmark interest rate in August 2021, and the financial authorities are actively dealing with excessive household debt. This article intends to take a look at characteristics of rising household debt after the pandemic outbreak, and to examine its effects and implications on the macroeconomy.

Characteristics of the recent increase in household debt

With loose financial conditions, the pace of growth in household debt has accelerated since 2020. While household income edged up 2.3% in 2020, household debt increased 9.2%, widening the disparity between income and debt growth. (Figure 1).1) Moreover, household debt jumped at a more rapid pace in the first half of 2021 to post a YoY increase of 11.3% as of the end of June.

With a steep rise in household debt relative to the real economy, the household debt-to-income ratio soared to 201% in 2020 (Figure 2). Given that the household income increased thanks to transfer incomes from the government, the pace of increase in household debt seems too fast. The net current transfer income of the household sector2) swelled to KRW 68 trillion in 2020 from KRW 31 trillion in 2019. The 2020 household income excluding current transfers, taxes, etc. (net primary income) is the same as the 2019 level of KRW 1,033 trillion. Were it not for the transfer income, the household debt-to-income ratio would have been 208%.

Compared to the pre-pandemic level, higher household savings are likely to continue well into 2021. Although private consumption showed signs of recovery in the first half of 2021 with a YoY increase of 2.4%, it remains below the GDP growth rate of 4.0%. The household savings rate is expected to exceed the pre-pandemic level on the back of payment of the 5th-round disaster relief funds from the government while restrictions on economic activity due to the resurgence of the Covid-19 hinder consumption.

Meanwhile, the household net buying trend in the stock market has continued (Figure 6). The net buying of stocks by retail investors reached KRW 63.8 trillion in 2020, far surpassing the pre-pandemic level, then further climbed to KRW 83.3 trillion during the period from January to September 2021. As leverage including credit loans has surged since 2020, a growing number of investors are showing stronger risk appetite.

A steep increase in household debt is raising macroprudential concerns. In the wake of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, major economies like the US and the UK have seen a downward adjustment in the household debt-to-income ratio through deleveraging, whereas such a decline has not been observed in Korea since 2005 as growth of household debt has steadily exceeded that of income.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) issued a warning that high household indebtedness would pose a serious potential risk to the macroeconomy based on its 2017 panel analysis on household debt by country. While an increase in household debt could stimulate consumption in the short term, the debt has negative effects in the medium term (Figure 7). In advanced countries where household debt ratios are higher than emerging economies, household indebtedness has a stronger effect of dampening consumption.6)

The results of the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions demonstrate that a slowdown in household consumption has been underway over the last decade (Figure 8). Households’ average propensity to consume has declined across income quintiles overall since 2011.7) The 2019 average consumption propensity of the second to fifth income quintiles is lower than the 2011 level by 8 to 11 percentage points, indicating that demand in the private sector has diminished.

Meanwhile, the flow of household savings into the real economy has weakened since the mid-2010s as companies’ funding shortfall has decreased.8) Companies utilize internal funding to make investments and if their internal funds are insufficient, they borrow from other economic agents. The net borrowing by non-financial firms surpassed the household savings level overall up until the early 2010s (Figure 10). Being used by firms for investments, household savings were channeled to the real economy. Since 2014, however, the net borrowing by firms has fallen far short of household savings, mainly due to internal funding growth and investment slowdown.9) As a result, the household savings have not been effectively provided to the real economy, which could undermine growth potential going forward.

The Bank of Korea and the Korean government are actively dealing with household indebtedness with a base rate hike and management of the aggregate household debt. With these policy measures in place, the growth trend of household debt is expected to show signs of abating down the road. However, it is noteworthy that household DSR (Debt Service Ratio)—the ratio of debt service payment to income—has been on a steady rise since 2016 (Figure 11). In this regard, thorough monitoring is needed to make sure that higher debt servicing pressures driven by rate hikes would not lead to a rise in credit risk. Rising interest rates would have repercussions for the whole economy, while vulnerable groups including the self-employed workers would bear the brunt of economic activity restrictions caused by the Covid-19. Under these circumstances, the government needs to provide well-targeted fiscal support to prevent credit risks from further spreading to the economy.

A strong rebound in the global economy has sparked concerns about inflation. Some advanced countries including Korea raised interest rates in the post-pandemic cycle, and major economies would see a shift in their monetary policies.10) Given that the increase in asset prices since the onset of the pandemic has been attributed to monetary easing by central banks around the world, a potential change in monetary policies could intensify volatility in asset prices. More attention should be paid to changes in economic conditions at home and abroad, whereas households need to reassess how much investment risk they are willing to take.

1) In this article, the net disposable income and the financial liabilities of households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISHs) are used as household income and household debt, respectively.

2) This is based on the net current transfer income (excluding insurance premiums and insurance claims) of households and NPISHs from Korea’s national accounts data. Over the past decade (from 2010 to 2019), this figure stayed around its annual average of KRW 31 trillion with little change.

3) A cautious approach is needed as household income and consumption are analyzed based on aggregate indices, not taking account of different economic conditions by income bracket.

4) However, it needs to be noted that the self-employed workers who have been hit hard by the Covid-19 shock have also raised funds through household loans. As of the end of March 2021, 35.0% of the loans taken out by self-employed borrowers (KRW 831.8 trillion) are included in household loans (Bank of Korea, 2021).

5) A panel analysis on 27 countries reveals that rising household debt pushes up housing prices, which further increases household debt again (IMF, 2017).

6) In this analysis, Korea is classified as advanced economies.

7) As for the first quintile income, the average consumption propensity is exceeding 100% with the consumption level surpassing the disposable income (households living in the red).

8) The fund shortages in this article refer to the net amount non-financial corporations borrow from other economic agents including households, rather than the total amount of borrowing.

9) In the 2000s, internal funding of non-financial firms increased to meet the demand for investment funds while the growth of investment slowed down after 2011 (Cho, S.H., 2018).

10) The Bank of Korea raised its base rate in August 2021 (from 0.5% to 0.75%), followed by interest rate hikes by the central bank of Norway (from 0.0% to 0.25%) in September and by Reserve Bank of New Zealand (from 0.25% to 0.5%) in October. Moreover, there is a growing possibility that the US Fed would begin tapering within this year.

References

Bank of Korea, 2021, Financial Stability Report: June 2021.

IMF, 2017, Household debt and financial stability. In Global Financial Stability Report (October), Chapter 2.

(Korean)

Cho, S.H., 2018, Investment and fundraising of Korea’s companies: changes and implications, Capital Market Focus 2018-21.