Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Publication date Oct. 08, 2019

Retirement benefits are a reward an employer provides to its employees in return for their service for a certain service period. They are paid in lump sum or an annuity based on a long-term implicit contract they established with the employer.1) In other words, retirement benefits should be regarded as a kind of liabilities employers should pay to their employees. To guarantee such payments, employers should hold sufficient reserves in advance. Korea’s Act on the Guarantee of Employees’ Retirement Benefits (GERB Act, hereinafter) obligates employers providing DB plans to maintain a statutory funding position - a ratio of pension assets to pension liabilities. When the company fails to do so, the law mandates the company to reserve additional assets to supplement the shortfall in three years.2) Furthermore, the GERB Act prescribes that when the company goes bankrupt, the retirement benefit claims are given priority and paid ahead of other unsecured claims, an additional guarantee to ensure employees can get their retirement benefits. This means the investors holding debt issued by a company with a low funding position are exposed to higher credit risk. The overall picture is that a company with a low funding position will see cash outflows to accumulate assets for their benefit promise, which might in the end increase the default risk of other debt and lower employers’ credit rating.

Based on the assumption, this article tries to analyze how employers’ funding position is related to their corporate debt ratings. The analysis is expected to confirm whether the funding position is another factor affecting corporate credit risk, alongside with the existing factors – a company’s size, profitability, growth potential, debt ratio, etc. that are known to affect corporate credit ratings.

Correlation of funding position and credit risk

As briefly mentioned above, employers’ funding position is in general known to affect their credit standing via the following two paths.3) First, cash outflows to replenish pension assets for future benefit payments increase employers’ financial constraints, and thereby raise their credit risk as well. Korea’s GERB Act mandates employers opting for DB plans to accumulate pension assets more than a minimum ratio against the standard policy reserve.4) And the law recommends that any shortfall from the minimal ratio be replenished in the following three years.5) This means employers with low funding positions are more likely to see more cash outflows to meet the minimum funding position, which increases the risk of liquidity shortages.

Aside from the growing liquidity risk of employers directly resulting from cash outflows to accumulate pension assets, this could also lead to a rather indirect impact of increased costs for equity financing for future investments. According to the pecking order theory, a company, when financing its investments, prefers cash and other internal reserves to external financing because internal financing is less costly.6) If the contribution to pension assets leads to a decrease in internal reserves of cash, this will increase a firm’s dependency on external financing and ultimately the financing costs, which could have a negative impact on the credit ratings of debt to be issued.

Second, because retirement benefit claims are given priority and paid off before other claims, investors in corporate debt are more exposed to risk, which could lower corporate debt ratings. As mentioned above, Korea’s GERB Act prescribes that retirement allowances and benefits should be paid ahead of other claims such as taxes and public charges, except for secured debt.7) If investors in debt whose issuer has a low funding position are in advance aware of the risk of higher default risk in their investments, it’s probable that the issuer’s debt ratings could be lowered, reflecting such investor expectations.

Characteristics of firms with sound funding positions

Based on the rationale provided above, here I analyze the relation between the funding position and corporate debt ratings based on financial statements of listed companies in Korea. The analysis target includes manufacturing companies listed on the KOSPI and KOSDAQ between 2011 and 2018, whose fiscal year ends in December. The actual sample includes a total of 2,456 companies. For corporate debt ratings, I use the most conservative rating among the ratings of Korea’s three major credit rating agencies.8) Ratings are converted to numeric scores, with the highest AAA rating scored 1, and the next highest rating scored 2, etc. Simply put, the higher the rating is, the lower the score gets in this analysis.9)

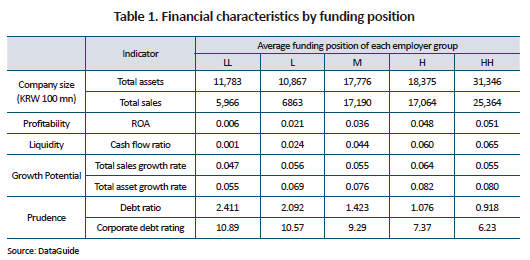

To gauge the differences in financial characteristics of over- and under-funded employers, I divided the employers in the sample in five groups (LL, L, M, H, HH) depending on the funding position level, and compared each group’s corporate size, growth potential, profitability, and other financial features. Table 1 shows the average of each group’s financial characteristics.

In terms of corporate size measured by total sales and total assets, companies with a high funding position tend to be larger than those with a low funding position. Also, the tendency of better funded groups’ higher ROA (operating profits/total assets) and cash flow ratio (operating cash flows/total assets) shows that employers with high profitability and stable cash flows contribute more to their plan assets.

Prudence indicators show that better funded employers have lower debt ratios and higher ratings, meaning financially sound companies tend to have higher funding positions. Overall, it is observed that better funded companies, as compared to companies with lower funding positions, are more likely to be larger in size and more profitable, and to have sound financial conditions.

Impact of function positions on corporate debt ratings

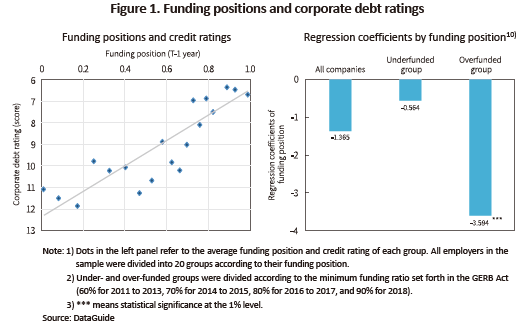

To see how pension funding positions are related to corporate debt ratings, I look at the correlation between corporate debt ratings for a period of 2011 to 2018 and the funding position in the previous year (refer to the left panel in Figure 1). The result indicates that companies with higher funding positions have higher credit ratings (lower scores), indirectly suggesting the possible impact of funding positions on credit risk. However, the result stems from a simple correlation analysis between two variables. For a more thorough analysis, other factors that might affect corporate credit ratings should be controlled.

In general, corporate size, profitability, growth potential, financial prudence, etc. are known to be factors affecting corporate credit ratings. Those factors might have affected the correlation between funding position and ratings in the left penal in Figure 1. For a more systematic analysis, it’s necessary to control the impact of those factors. Also notable here is that funding positions could result from some unobservable company-specific features.

Taking into account this, the right panel in Figure 1 shows the result of a panel regression analysis with firm-fixed effects where the dependent variable is the corporate credit rating and the explanatory variables are the funding position, debt ratio, market-to-book ratio, corporate size (natural logarithm of total assets), ROA, companies, and year dummies.11) The coefficient of the previous year funding position turns significantly negative in overfunded groups, confirming that companies with higher funding positions have lower credit risk. Although not highly significant, the coefficient is also negative in all companies and underfunded groups. What this means is that, with other factors controlled, pension funding positions have a significant impact on financial risk.

Implications

Currently, the low investment returns on retirement pension assets has been the focus of market participants in Korea. However, in major developed counties including the US and the UK with a longer history of retirement pensions, the broad impacts of the funding status of retirement pensions on employers’ credit risk, stock price volatility, investment expenditures, and overall financial status have been the focus of abundant research. Admittedly, given Korea’s short history of retirement pension scheme, its lower proportion of retirement pension benefits in total assets,12) and the lump-sum, instead of annuity in developed countries, structure in DB plans, it may not be highly likely that retirement pensions’ financial status becomes a serious threat to employers, as was the case in developed countries.13)

However, Korean companies’ retirement pension liabilities and their volatility are expected to rise continuously given the new regulatory as well as economic environments around the retirement pension scheme, e.g., new liability valuation under K-IFRS since 2011, continued low growth and low interest rates, population ageing, etc. In the long run, it’s impossible to completely rule out the possibility of retirement pensions’ financial risk being a considerable burden on employers. With regard to this matter, the analysis in this article demonstrates the possible impact of the funding status of pension plans on employers’ credit risk.

In DB plans, it’s the employer who makes all critical decisions with regard to the whole process of introducing the retirement pension scheme, contributing to plan assets, managing the plan assets, etc. Instead of viewing retirement benefits as a reward to employees for their service, firms need to recognize pension liabilities as real debt and be more proactive in improving efficiency in managing plan assets.

1) Ippolito (1985)

2) As of 2019, the mandated minimum funding position stands at 90%, which will rise to 100% on January 1, 2021.

3) Previous literature on the impact of employers' funding position on credit ratings includes Choi and Noh (2017), and Ji et al. (2017), showing that the impact is only significant in employers whose funding position is below the statutory level set forth in the GERB Act. Overseas literature analyzing the impact of pension liabilities on corporate credit ratings and credit spreads include Cardinale (2007), and McKillop & Pogue (2009). They show that the level of pension liabilities could be a major predictor for credit ratings and credit spreads.

4) The standard policy reserve means the larger of the followings: 1) The amount calculated by the method prescribed by Ordinance of the Ministry of Employment and Labor, which is obtained by deducting the present value of the estimated revenues accruing from contributions for the future period of service from the present value of the estimated expenses incurred in paying benefits for the contribution period until the estimated time of retirement; 2) The amount calculated by the method prescribed by Ordinance of the Ministry of Employment and Labor, using the estimated expenses incurred in paying benefits for the contribution period until the last day of the business year concerned of a person who is or was a participant (Article 16 of the GERB Act).

5) Article 5 through Article 7 of the Enforcement Decree of the GERB Act.

6) According to Myers & Majluf (1984), a company finances itself by choosing the most cost-efficient way first in the order of internal reserves, low-risk debt, high-risk debt, and stock issuance.

7) Retirement allowances that an employer is obligated to pay, benefits under a defined benefit plan, delinquent contributions and interest for arrears on delinquent contributions of the contributions under a defined contribution plan, and delinquent contributions and interest for arrears on delinquent contributions of the contributions under an individual retirement pension plan (hereinafter referred to as "etirement benefits, etc.") shall be paid in preference to taxes, public charges and other claims, except for claims secured by pledges or mortgages on the whole property of the employer (Article 12-1, GERB Act). And retirement benefits, etc. for the final three years of service shall be paid in preference to claims secured by pledges or mortgages, or to taxes, public charges, and other claims on the whole property of an employer (Article 12-2, GERB Act). Simply put, claims and retirements are paid in the order of 1) retirement benefits, etc. for the final three years of service; 2) taxes and public charges paid before pledges or mortgages; 3) claims secured by pledges or mortgages; 4) retirement benefits, etc.; and 5) taxes, public charges and other claims.

8) Korea Asset Pricing, NICE Investors Service, Korea Investors Service.

9) Among a total of 22 credit ratings, the highest AAA is scored 1 with the lowest D being 22.

10) In a panel regression analysis on all companies analyzed, the coefficient of other variables stands at 4.567 (debt ratio), -0.448(market-to-book ratio), –1.051 (company size), and –7.597 (ROA), all of which, except for the ROA coefficient, are statistically significant at the 5% and 1% levels. R2, showing explanatory power of explanatory variables in regression analysis, stands at 11.3%, 18.7%, and 13.3%, for all companies, underfunded groups, and overfunded groups, respectively.

11) To control endogeneity, all explanatory variables in the regression analysis are the figures from the previous fiscal year.

12) In listed companies analyzed in this article, the ratio of pension liabilities over total assets stands at approximately 3% (consolidated financial statements) on average as of 2018.

13) When the IT bubble burst in the US in the early 2000s, the stock prices and interest rate tumbled together. This seriously deteriorated the financial condition of retirement pension in manufacturing firms such as steel, aviation, automobile, etc. where DB plans accounted for a high proportion. And this put some of the firms into a crisis. A case in point is Delphi, GM’s child company, which filed for a bankruptcy protection in 2005 due to its pension liabilities as large as 30% of its annual sales.

References

Cardinale, M., 2007, Corporate pension funding and credit spreads, Financial Analysts Journal 63(5), 82-101.

Ippolito, R. A., 1985, The labor contract and true economic pension liabilities. The American Economic Review 75(5), 1031-1043.

Mckillop, D., Pogue. M., 2009, The influence of pension plan risk on equity risk and credit ratings: A study of FTSE 100 Companies, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 8(04), 405.

Myers, S.C., Majluf, N.S., 1984, Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have, Journal of Financial Economics 13(2), 187-221.

(Korean)

Chi, S. Y., Sung, J., Kim, Y. S., 2017, The influence of DB solvency risk on the financial risk of DB sponsoring firm: A panel analysis of KOSPI200, The Journal of Risk Management 28(4), 73-93.

Choi, J. S., Noh, J. H., 2017, The effects of pension funding levels on credit ratings, Korean Journal of Financial Studies 46(2), 305-342.