Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Analyses on Year-end Retail Net Selling in Korea’s Stock Market, and the Implications

Publication date Nov. 24, 2020

Summary

A massive inflow of retail investors to Korea’s stock market this year has raised concern about the impact of their possible year-end net selling in the market. According to a series of empirical analyses in this article, their year-end net selling could have been affected by not only retail selling for realizing returns as part of their tax strategies, but also institutional buying for dividend arbitrage. Also, the retail net selling impacts on stock prices depend on the level of institutional demand: Price declines by retail net selling are not observed in the stocks for which institutional investors have high year-end demand.

However, economic shocks and the expected dividend decrease in listed companies in Korea are expected to drag down institutional demand at year-end. It’s important to note that this—combined with retail investors’ continuous risk preference—could possibly derail the way net selling used to impact the market.

However, economic shocks and the expected dividend decrease in listed companies in Korea are expected to drag down institutional demand at year-end. It’s important to note that this—combined with retail investors’ continuous risk preference—could possibly derail the way net selling used to impact the market.

As retail investors stormed into stocks this year, there have been growing concerns over a possible market shock at the end of this year as large shareholders1) could possibly begin to dump their shares for avoiding taxes that will kick in next year. Behind such concerns are Korea’s abrupt increase in the retail investor base and tougher capital gains tax. Recently, the Ministry of Economy and Finance finally decided to keep the current taxation threshold of KRW 1 billion for determining large shareholders, aiming to avoid unnecessary market unrest. However, there is a lingering possibility for retail investors to try to take profits by net selling their shares at the end of this year more drastically than they did in the past because Korea’s stock market continues its rally this year.

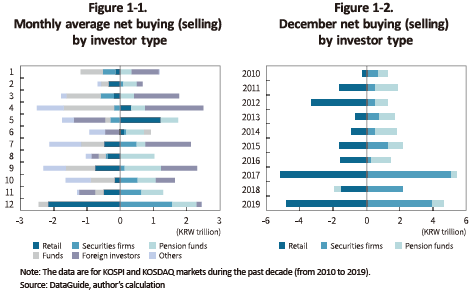

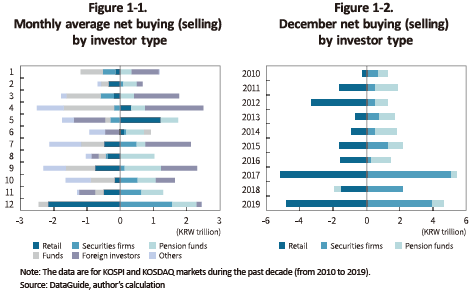

The inference about possible net-selling among large shareholders—in other words, a tendency of order imbalance2) among retail investors towards year-end—seems somewhat reasonable given that capital gains tax is levied depending on one’s year-end shareholding ratio or amount. As illustrated in Figure 1-1, retail investors are observed more likely to net sell their stocks in December than in other months, and such an order imbalance leaning towards selling became stronger recently (Figure 1-2).

However, because those data provide no picture about which entity is initiating trades, a closer look at the order imbalance among retail investors should also consider the buying demand of other entities. In this regard, this article tries to analyze the order imbalance centering on year-end net selling among retail investors, taking into account various trade factors surrounding retail as well as institutional investors. The findings are expected to provide crucial implications.

What initiates retail selling and institutional buying?

A growing incentive for retail selling at year-end is not limited to Korea. Previous research has already confirmed that retail investors in the US show a stronger selling tendency towards year-end for minimizing capital gains tax imposed on equity investment (Ritter, 1988). Because most developed countries allow investment gains to be offset by losses, investors in those countries tend to sell stocks at a loss at the end of each year as part of attempt to minimize capital gains tax. However, it seems reasonable to expect investors in Korea’s stock market—where such offsetting is not permissible—to have a strong incentive to realize their gains at year-end.3)

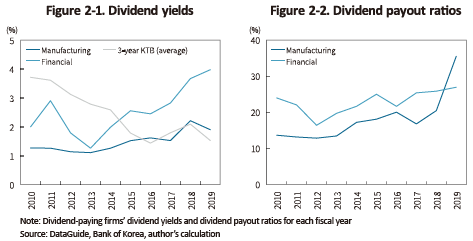

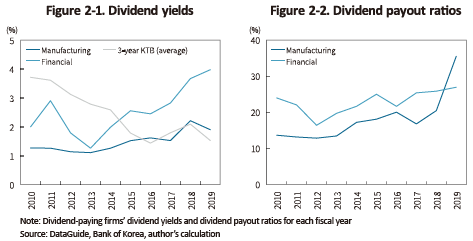

Thus far, Korea’s stock market tends to observe a net buying of securities firms and pension funds in every December as illustrated in Figure 1-1. According to Figure 1-2, the percentage of year-end net buying is increasing particularly in securities firms. The net buying of securities firms has abruptly risen since the mid-2010s presumably due to investment for dividends and related program trading. Behind this is a continuous increase in dividend yields since the 2010s. Figure 2-1 and Figure 2-2 demonstrate dividend yields and payout ratios of dividend-paying firms, according to which dividend yields of listed companies in Korea have been on the steady rise, and surpassed 3-year Korea Treasury Bond (KTB) yields in 2015. Furthermore, their increase in dividend payout ratios makes investment for dividends even more attractive amid the low interest rate environment.

Notably, about 98% of Korea’s listed firms use December as fiscal year-end, with 93% of dividend-paying firms offering only annual dividend. This implies that the end of each year is a critical point of time for not only taxation on large shareholders but also dividend payouts.4) This provides a potent driver for change in trading behavior among various types of investors.

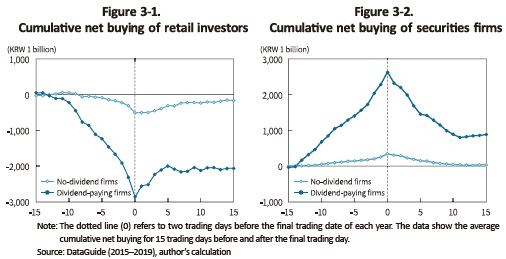

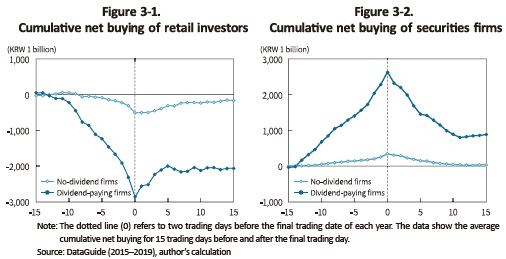

Before an in-depth analysis, it’s worth looking at the overall net buying trend among retail investors as well as securities firms on a cumulative basis. Because a trade is completed on T+2 (two days after the trade date in Korea), the actual changes in trading patterns are observed between the last trading day of each year and two days before that. Figure 3-1 and Figure 3-2 show the trend of cumulative net buying of two groups of stocks (those that paid or didn’t pay dividends in the past) by two groups of investors (retail investors and securities firms). As illustrated by the results, securities firms are found to continue their net buying of dividend-paying stocks before turning to net selling after the record date, where retail investors exhibit an exactly opposite pattern. What the results imply could be summed up to two points. First, institutional investors are likely to increase their short-term net buying towards year-end amid expectations for higher dividend payout ratios. Second, this could possibly make year-end retail net selling even stronger than the past.

Factors and impacts of the year-end order imbalance towards retail net selling

To sum up, it’s possible to expect the year-end order imbalance towards retail net buying to be affected by a combination of two factors: Retail investors try to realize their gains by dumping their holdings (“retail selling factor”)5); and institutional investors, mainly securities firms, buy more for dividend arbitrage (“institutional buying factor”).

In analyzing the impact of the aforementioned factors on retail investors’ order imbalance, I first measured the buy-sell order imbalance of retail investors,6) and used past dividend yields7) and average unrealized capital gain rates estimated in this article as proxy for the two factors. This article tries to estimate the unrealized capital gain rate based on market data, more concretely, the ratio between retail investors’ average buying price of one stock and its actual price at a certain point of time (e.g., early December). Those estimates mean the average unrealized capital gain rate of retail investors holding that stock. The primary assumption in this analysis is that the higher the rate is, the higher will the incentive for selling that stock for realizing gains be.8)

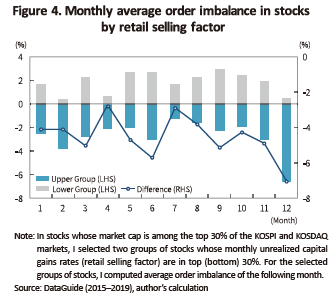

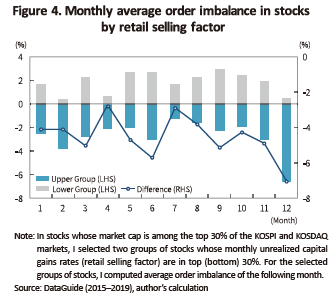

Among the stocks included in the sample,9) I selected two groups of stocks whose monthly unrealized capital gains (retail selling factor) are ranked in top (bottom) 30%. Then, both groups’ next-month average retail order imbalance was analyzed. As shown in Figure 4, there is a constant order imbalance arising from the retail selling factor for the whole analysis period. In short, an order imbalance towards net selling (buying) exists in stocks with a high (low) incentive for gain realization. Above all, the imbalance difference tends to widen particularly in December. The monthly average imbalance difference between the upper and lower groups is found to rise sharply in December, particularly in the upper group. This could certainly be attributable to the year-end retail selling factor due to taxes and other reasons, but the institutional buying factor described above could be also part of the phenomenon.

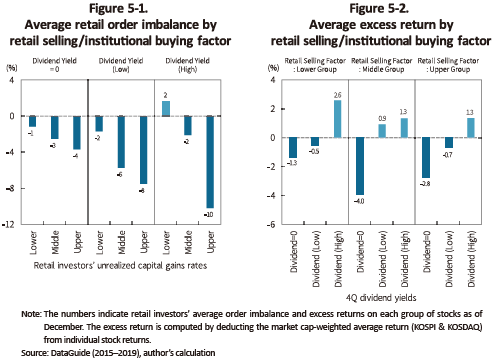

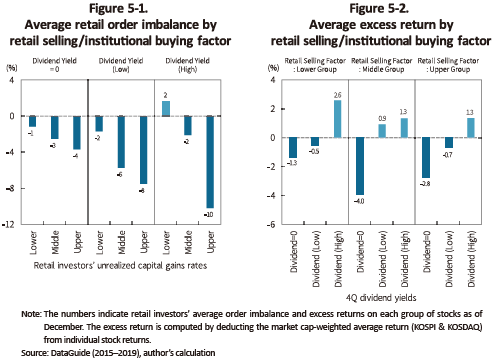

For taking into account the institutional buying factor, this section tries to measure the average order imbalance of retail investors at the end of December. The analysis sample is classified into three groups depending on both the retail selling factor (unrealized capital gains rates) and the institutional buying factor (dividend yields), which makes up a total of nine groups. As demonstrated in Figure 5-1, an overall order imbalance towards selling is found in December, but that imbalance is affected by a combination of both factors mentioned above. First, the higher the retail selling factor, the higher the order imbalance in retail investors. However, if the higher retail selling factor meets with a stronger incentive for investing for dividend, this is found to widen retail investors’ order imbalance. Such a result can be possibly interpreted as that retail investors’ year-end order imbalance towards selling is affected by the retail selling factor significantly, as well as institutional investors’ short-term demand factor such as dividends.

Last but not least, retail investors’ order imbalance could impose the following impacts on the market. If retail investors have a strong selling factor, the stock returns during the same period could be deeply related to retail investors’ order imbalance. Figure 5-2 shows the correlation between dividend yields and year-end excess returns in three groups of stocks classified by retail selling factor. Although individual stock returns are partly affected by the retail selling factor, the results suggest that they are more deeply related to dividend yields (institutional investors’ year-end investment demand). The returns on high-dividend stocks in high demand are found to top the market return during the same period. However, the stocks in lower year-end demand among institutional investors—for instance, stocks with a zero dividend yield—are found to lose value depending on the retail selling factor. As such, the prices of stocks in high demand among institutional investors could have been insignificantly affected by retail investors’ order imbalance towards selling, implying that year-end stock prices have been affected more by institutional investors who substantially perform a price discovery function, rather than retail investors.

Conclusion

A series of analyses in this article can be summed up as follows. Retail investors’ order imbalance towards selling is clearly affected by retail selling for realizing investment gains at the end of each year for the purpose of tax strategies. However, also in play here is the buying factor of securities firms and other institutional investors. However, institutional investors who continue their year-end net buying are found to have a larger impact on stock prices, while the price declines stemming from retail net selling are concentrated in stocks in lower demand among institutional investors. This is presumably because those stocks with less demand are only a fraction of market cap, thus their year-end retail net selling imposing only a meager impact on the overall stock market.

However, retail investors flocked to the stock market after the Covid-19 shock, which helped the market rebound. This makes it more likely that retail investors have an incentive—that is higher than the past—to reduce their capital gains tax by selling their holdings at the end of the year. Another issue requiring a great level of wariness is the expected dividend decrease in listed companies due to earnings declines, which could possibly derail the way net selling used to impact the market. Nevertheless, one thing looks quite clear. Any price disparity arising from a short-term demand-supply imbalance will be eased sooner or later by another entity in the market as long as the fundamentals remain intact. At a time when the market is full of retail demand for risky assets, the entity trying to buy on the dip is highly likely to be other retail investors.

1) The “large shareholder” here refers to any investor who is subject to capital gains tax from investment in listed stocks in Korea.

2) An order imbalance in a specific group of investors means the level of their trades leaning towards selling of buying.

3) This is a phenomenon of asymmetric risk preference/aversion with regard to losses/gains based on the prospect theory. In general, retail investors are known to realize gains ahead of losses. Although nothing is clearly known about year-end trading behavior, retail investors in Korea are highly likely to realize gains—ahead of losses—at the end of this year, as part of their effort to save tax on capital gains or to prepare for the possibility to be a large shareholder.

4) In Korea, the last trading day of the previous fiscal year becomes the record date as the provisions in Article 360(3) of the Commercial Act could be interpreted as such.

5) Retail investors’ selling for realizing investment gains could be heavily affected by year-end tax incentives as well (Hwang, 2020). Due to data constraints, however, the “retail selling factor” in this article is loosely defined as any incentive for retail investors to sell for taking profits out of their investment.

6) The buying-selling order imbalance of retail investors refers to a ratio of the amount of net selling to the sum of the selling and buying, which is ranged from -100% (net selling) to 100% (net buying).

7) A dividend yield is computed by the ratio of the dividend paid out in the previous fourth quarter (or year in terms of annual dividends) and the stock price in early December to minimize the hindsight bias.

8) Using the Grinblatt and Han (2005) methodology, this article uses retail investors’ average buying price and trading volume for each stock. This is based on previous research that has explained the January effect in the US stock market with a tax-loss selling hypothesis (e.g., Reignanum, 1983).

9) Retail investors’ year-end net selling is observed only in large-cap stocks. Hence, our analysis sample includes large-cap common stocks whose market cap is ranked in the top 30% of the KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets. The results are qualitatively similar if the sample also includes mid-cap and small-cap stocks.

References

Grinblatt, M., Han, B., 2005, Prospect theory, mental accounting, and momentum, Journal of Financial Economics 78(2), 311-339.

Reinganum, M. R., The anomalous stock market behavior of small firms in January: Empirical tests for tax-loss selling effects, Journal of Financial Economics 12(1), 89-104.

Ritter, J. R., The Buying and Selling Behavior of Individual Investors at the Turn of the Year, Journal of Finance 43(3), 701-717.

(Korean)

Hwang, S.W, 2020, Analysis on stock trading behavior to avoid being a large shareholder and the implications for capital gains tax, KCMI Issue Paper 20-09.

However, because those data provide no picture about which entity is initiating trades, a closer look at the order imbalance among retail investors should also consider the buying demand of other entities. In this regard, this article tries to analyze the order imbalance centering on year-end net selling among retail investors, taking into account various trade factors surrounding retail as well as institutional investors. The findings are expected to provide crucial implications.

What initiates retail selling and institutional buying?

A growing incentive for retail selling at year-end is not limited to Korea. Previous research has already confirmed that retail investors in the US show a stronger selling tendency towards year-end for minimizing capital gains tax imposed on equity investment (Ritter, 1988). Because most developed countries allow investment gains to be offset by losses, investors in those countries tend to sell stocks at a loss at the end of each year as part of attempt to minimize capital gains tax. However, it seems reasonable to expect investors in Korea’s stock market—where such offsetting is not permissible—to have a strong incentive to realize their gains at year-end.3)

Thus far, Korea’s stock market tends to observe a net buying of securities firms and pension funds in every December as illustrated in Figure 1-1. According to Figure 1-2, the percentage of year-end net buying is increasing particularly in securities firms. The net buying of securities firms has abruptly risen since the mid-2010s presumably due to investment for dividends and related program trading. Behind this is a continuous increase in dividend yields since the 2010s. Figure 2-1 and Figure 2-2 demonstrate dividend yields and payout ratios of dividend-paying firms, according to which dividend yields of listed companies in Korea have been on the steady rise, and surpassed 3-year Korea Treasury Bond (KTB) yields in 2015. Furthermore, their increase in dividend payout ratios makes investment for dividends even more attractive amid the low interest rate environment.

Before an in-depth analysis, it’s worth looking at the overall net buying trend among retail investors as well as securities firms on a cumulative basis. Because a trade is completed on T+2 (two days after the trade date in Korea), the actual changes in trading patterns are observed between the last trading day of each year and two days before that. Figure 3-1 and Figure 3-2 show the trend of cumulative net buying of two groups of stocks (those that paid or didn’t pay dividends in the past) by two groups of investors (retail investors and securities firms). As illustrated by the results, securities firms are found to continue their net buying of dividend-paying stocks before turning to net selling after the record date, where retail investors exhibit an exactly opposite pattern. What the results imply could be summed up to two points. First, institutional investors are likely to increase their short-term net buying towards year-end amid expectations for higher dividend payout ratios. Second, this could possibly make year-end retail net selling even stronger than the past.

To sum up, it’s possible to expect the year-end order imbalance towards retail net buying to be affected by a combination of two factors: Retail investors try to realize their gains by dumping their holdings (“retail selling factor”)5); and institutional investors, mainly securities firms, buy more for dividend arbitrage (“institutional buying factor”).

In analyzing the impact of the aforementioned factors on retail investors’ order imbalance, I first measured the buy-sell order imbalance of retail investors,6) and used past dividend yields7) and average unrealized capital gain rates estimated in this article as proxy for the two factors. This article tries to estimate the unrealized capital gain rate based on market data, more concretely, the ratio between retail investors’ average buying price of one stock and its actual price at a certain point of time (e.g., early December). Those estimates mean the average unrealized capital gain rate of retail investors holding that stock. The primary assumption in this analysis is that the higher the rate is, the higher will the incentive for selling that stock for realizing gains be.8)

Among the stocks included in the sample,9) I selected two groups of stocks whose monthly unrealized capital gains (retail selling factor) are ranked in top (bottom) 30%. Then, both groups’ next-month average retail order imbalance was analyzed. As shown in Figure 4, there is a constant order imbalance arising from the retail selling factor for the whole analysis period. In short, an order imbalance towards net selling (buying) exists in stocks with a high (low) incentive for gain realization. Above all, the imbalance difference tends to widen particularly in December. The monthly average imbalance difference between the upper and lower groups is found to rise sharply in December, particularly in the upper group. This could certainly be attributable to the year-end retail selling factor due to taxes and other reasons, but the institutional buying factor described above could be also part of the phenomenon.

Conclusion

A series of analyses in this article can be summed up as follows. Retail investors’ order imbalance towards selling is clearly affected by retail selling for realizing investment gains at the end of each year for the purpose of tax strategies. However, also in play here is the buying factor of securities firms and other institutional investors. However, institutional investors who continue their year-end net buying are found to have a larger impact on stock prices, while the price declines stemming from retail net selling are concentrated in stocks in lower demand among institutional investors. This is presumably because those stocks with less demand are only a fraction of market cap, thus their year-end retail net selling imposing only a meager impact on the overall stock market.

However, retail investors flocked to the stock market after the Covid-19 shock, which helped the market rebound. This makes it more likely that retail investors have an incentive—that is higher than the past—to reduce their capital gains tax by selling their holdings at the end of the year. Another issue requiring a great level of wariness is the expected dividend decrease in listed companies due to earnings declines, which could possibly derail the way net selling used to impact the market. Nevertheless, one thing looks quite clear. Any price disparity arising from a short-term demand-supply imbalance will be eased sooner or later by another entity in the market as long as the fundamentals remain intact. At a time when the market is full of retail demand for risky assets, the entity trying to buy on the dip is highly likely to be other retail investors.

1) The “large shareholder” here refers to any investor who is subject to capital gains tax from investment in listed stocks in Korea.

2) An order imbalance in a specific group of investors means the level of their trades leaning towards selling of buying.

3) This is a phenomenon of asymmetric risk preference/aversion with regard to losses/gains based on the prospect theory. In general, retail investors are known to realize gains ahead of losses. Although nothing is clearly known about year-end trading behavior, retail investors in Korea are highly likely to realize gains—ahead of losses—at the end of this year, as part of their effort to save tax on capital gains or to prepare for the possibility to be a large shareholder.

4) In Korea, the last trading day of the previous fiscal year becomes the record date as the provisions in Article 360(3) of the Commercial Act could be interpreted as such.

5) Retail investors’ selling for realizing investment gains could be heavily affected by year-end tax incentives as well (Hwang, 2020). Due to data constraints, however, the “retail selling factor” in this article is loosely defined as any incentive for retail investors to sell for taking profits out of their investment.

6) The buying-selling order imbalance of retail investors refers to a ratio of the amount of net selling to the sum of the selling and buying, which is ranged from -100% (net selling) to 100% (net buying).

7) A dividend yield is computed by the ratio of the dividend paid out in the previous fourth quarter (or year in terms of annual dividends) and the stock price in early December to minimize the hindsight bias.

8) Using the Grinblatt and Han (2005) methodology, this article uses retail investors’ average buying price and trading volume for each stock. This is based on previous research that has explained the January effect in the US stock market with a tax-loss selling hypothesis (e.g., Reignanum, 1983).

9) Retail investors’ year-end net selling is observed only in large-cap stocks. Hence, our analysis sample includes large-cap common stocks whose market cap is ranked in the top 30% of the KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets. The results are qualitatively similar if the sample also includes mid-cap and small-cap stocks.

References

Grinblatt, M., Han, B., 2005, Prospect theory, mental accounting, and momentum, Journal of Financial Economics 78(2), 311-339.

Reinganum, M. R., The anomalous stock market behavior of small firms in January: Empirical tests for tax-loss selling effects, Journal of Financial Economics 12(1), 89-104.

Ritter, J. R., The Buying and Selling Behavior of Individual Investors at the Turn of the Year, Journal of Finance 43(3), 701-717.

(Korean)

Hwang, S.W, 2020, Analysis on stock trading behavior to avoid being a large shareholder and the implications for capital gains tax, KCMI Issue Paper 20-09.