Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Real Estate Shadow Banking: Risk Assessment and Countermeasures

Publication date Mar. 07, 2023

Summary

Shadow banking for Korea’s real estate sector is expanding at a rapid pace, which raises concerns about systemic risk. Real estate shadow banking represents a greater presence in Korea relative to the size of its economy, is highly connected with the capital market and entails a high level of complexity. Compared to other non-bank financial institutions, small-to-medium-size firms tend to engage in real estate shadow banking more actively, potentially resulting in a string of losses in the entire sector. Korea’s real estate shadow banking has long, complicated financing intermediation channels and uses high leverage. Accordingly, the insolvency in real estate shadow banking could not only spread across financial institutions but also bring about a slowdown in the real economy, which requires caution. Against this backdrop, Korea’s financial authorities need to consider shadow banking regulations implemented by international financial supervisory organizations. Based on such regulations, they should curb the rapid growth of real estate shadow banking, strengthen information transparency criteria, and conduct stress tests on a regular basis, aiming for stepping up risk management for real estate shadow banking.

Current state of shadow banking for the real estate market

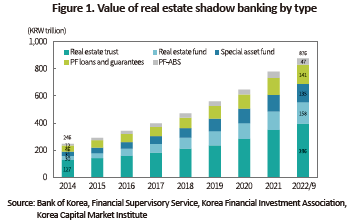

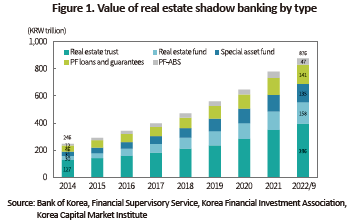

Shadow banking is growing rapidly in Korea’s real estate market. It is a term used to describe non-bank financial institutions that engage in services similar to those of traditional banks but fall outside the realm of normal regulated banking, or financial investment instruments provided by such institutions. This article defines as real estate shadow banking the financial instruments provided by financing or credit intermediaries by means of real estate, including project financing (PF) loans and guarantees, PF asset-backed securities (PF-ABS), real estate trusts,1) real estate funds and special asset funds. In Korea, real estate shadow banking is worth KRW 876 trillion as of end-September 2022, representing a 3.6-fold increase from KRW 246 trillion at the end of 2014 and the average annual growth of 17.8% (Figure 1). Given an average annual increase of 7.8% in the loan balance of commercial banks during the same period, shadow banking in Korea’s real estate market has grown almost 2.5 times faster than general banks’ indirect financing. By type, real estate funds, special asset funds and PF-ABS have experienced a four- or five-fold rise while real estate trusts and PF loans and guarantees have tripled or quadrupled. This suggests that compared to banks’ indirect financing, all types of real estate shadow banking have expanded at a faster pace.

If property prices take a nosedive or real estate financing intermediaries become insolvent amid the rapid expansion of real estate shadow banking, this could trigger systemic risk, which requires caution. Real estate shadow banking has long, complicated financing intermediation channels, is closely linked to the bond and short-term funding markets, and uses high leverage. Accordingly, the insolvency in real estate shadow banking could not only incur a series of losses in financial institutions but also intensify volatility in the financial market and bring about a slowdown in the real economy. A case in point is the liquidity crunch related to real estate PF that occurred in the second half of 2022. This demonstrates well that even a single incident in the real estate shadow banking sector can increase volatility across the financial market, thereby leading to a real economic downturn. Against this backdrop, this article assesses the risk level of Korea’s real estate shadow banking and presents risk management strategies to prevent real estate shadow banking from posing systemic risk.

Risk assessment for real estate shadow banking

When selecting major financial institutions or measuring systemic risk levels within a financial system, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) usually consider size, interrelation, complexity and factors specific to a country.2) In terms of the four aspects mentioned above, Korea’s real estate shadow banking is experiencing a rapid increase in risk levels, which likely triggers systemic risk.

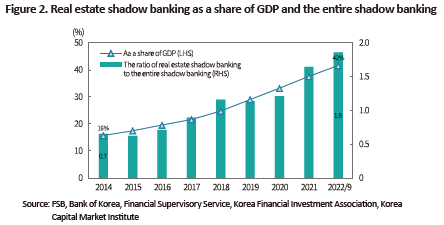

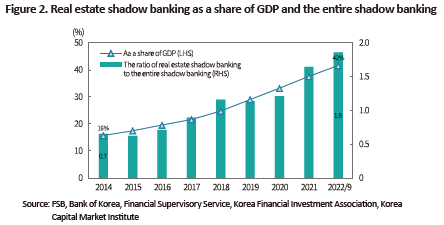

First, the proportion of real estate shadow banking in the Korean economy is rapidly increasing. Real estate shadow banking was responsible for only 16% of Korea’s GDP at the end of 2014 but swelled to 42% as of end-September 2022, taking up almost half of the GDP (Figure 2). It has increasingly accounted for a greater share in terms of the total value of Korea’s shadow banking. According to Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation published by the FSB,3) Korea’s real estate shadow banking was estimated at KRW 621 trillion at the end of 2014, of which real estate shadow banking was responsible for around 40%. At the end of 2021, the share of real estate shadow banking in the entire shadow banking sector surged rapidly to 62%. As for shadow banking, the ratio of real estate to the total excluding the real estate sector soared to 1.9 from 0.7 during the same period. It should be noted that real estate shadow banking has a close relation to assets and liabilities held by financial institutions, construction firms and households and shows high sensitivity to property prices. For these reasons, its fast-paced growth beyond a certain range should be viewed as a signal for greater systemic risk. If property prices plunge and consequently, real estate shadow banking intermediaries face the risk of insolvency, losses could be swiftly transmitted to other financial institutions or construction firms. The resultant fire-sale of real estate holdings may cause a sharper drop in property prices, thereby creating a vicious circle.

Second, Korea’s real estate shadow banking is highly interconnected to the capital market. Real estate PF secures funding from bridge loans and PF loans, which are usually intermediated by non-bank financial institutions including securities firms, insurance firms and specialized credit finance business entities. In the case where a real estate PF contractor issues ABS by using PF loans as a security via a special purpose company (SPC), a securities firm usually provides a debt guarantee for the issuance. If conditions become tighter for issuing PF asset-backed commercial paper (PF-ABCP) and PF asset-backed short-term bonds (PF-ABSTB) in the capital market, the securities firm and PF contractor could struggle with financial crunch. In the fourth quarter of 2022, bond yields climbed sharply and KEPCO issued a massive amount of corporate bonds. The subsequent supply and demand imbalance in the bond market obstructed the rollover of a large amount of PF-ABCP and PF-ABSTB, making PF business entities financially strapped. This is a prime example that the capital market has adverse effects on real estate shadow banking. In contrast, insolvency in real estate shadow banking could bring about greater volatility in the capital market. If a PF business entity becomes insolvent, it could incur a huge loss in not only non-bank financial institutions extending PF loans or providing debt guarantees, but also a number of individuals and financial institutions that invested in relevant trusts, funds and PF-ABS. In this case, the capital market is likely to see greater volatility due to the panic selling of financial investment products.

Third, Korea’s real estate shadow banking entails a high level of complexity and thus, could exacerbate systemic risk in the event of any insolvency event. As for real estate PF loans and debt guarantees, the risk of underlying assets is restructured through a credit and maturity adjustment and excessive leverage is used via some channels. For instance, a real estate PF contractor can make a division between equity-based PF and debt-based PF for financing. Debt-based PF is classified into senior, mid-risk and subordinated categories through structuring and is used to raise funds from numerous retail and institutional investors through a credit adjustment. Real estate PF-ABS allows investors to adjust maturities. A real estate PF business entity needs about three years to complete the sale of building units and usually issues a three-month PF-ABCP or PF-ABSTB for financing, which likely exposes it to maturity mismatches. If the issuance of PF-ABS hits a snag at least once during the three-year period, a relevant financial institution or construction firm could suffer huge losses in the real estate PF stage. As for PF debt guarantees by securities firms and warranted completion by real estate trusts, performance obligation arising from insolvency conditions is intricately described and the terms of a contract are not standardized. Furthermore, real estate funds and special asset funds also enable credit and maturity adjustments and have risks related to counterparties, exchange rate fluctuations and liquidity. This implies that real estate shadow banking is exposed to greater complexity as a whole.

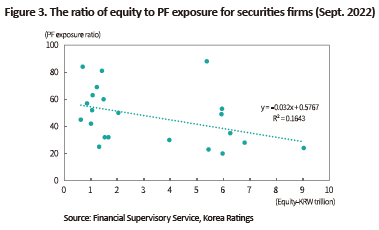

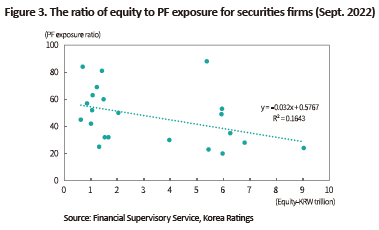

Fourth, small- and medium-sized non-bank financial institutions are more likely to engage in high-risk real estate shadow banking. PF loans and debt guarantees fall into the category of high-risk real estate shadow banking. Notably, small-to-medium-size securities firms and specialized credit finance business entities—low in equity value and less capable of managing risks—have increased their exposure to PF loans and debt guarantees. This article analyzes 22 securities firms that extended bridge loans and provided debt guarantees to real estate PF as of end-September 2022. In terms of the ratio of equity to PF exposure, those with a smaller amount of equity show a tendency of having higher exposure to PF (Figure 3) within statistically significant levels (Figure 3). In PF loans and debt guarantees, higher fees are commonly charged and a lower amount of risk-weighted assets is reflected in the net capital ratio. This may explain why small-to-medium-size financial institutions have expanded PF loans and debt guarantees. If such firms that are less capable of dealing with risks increase their exposure to PF, it could have a negative knock-on effect on the financial health of other institutions when real estate shadow banking becomes fragile, which requires extra caution.

Risk management strategies for real estate shadow banking

In short, real estate shadow banking in Korea has achieved rapid growth, represents a bigger presence relative to the size of its economy, is highly interconnected with the capital market, and entails greater complexity. Among non-bank financial institutions, small-to-medium-size ones are more likely to provide real estate shadow banking services. This means that a sharp drop in property prices may trigger insolvency in the entire real estate shadow banking sector. In terms of size, interrelation, complexity and Korea-specific factors, the chances are that real estate shadow banking will be more vulnerable to systemic risk in Korea.

Shadow banking can play a positive role in supplying venture capital as a substitute for the traditional banking system. But its excessive growth could bring about systemic risk. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, international financial supervisory authorities presented risk management strategies for shadow banking including curbing the growth pace of shadow banking, strengthening information transparency criteria and adopting regular stress tests. In line with such regulatory measures, Korea’s financial authorities should reinforce regulations and oversight to prevent real estate shadow banking from threatening financial stability.

First of all, prudential regulations should be tightened for non-bank financial services firms to hinder the fast-paced growth of loans and debt guarantees for real estate PF, real estate trusts for warranted construction completion, and PF-ABS, all of which are complex, high-leverage financial vehicles intertwined with the capital market. The formula for risk-weighted assets reflected in the net capital ratio needs to be modified while the calculation of the leverage ratio and the liquidity ratio should be improved. On top of that, it is necessary to step up monitoring of each risk factor in the entire real estate shadow banking sector, aiming for identifying the possibility of insolvency and the risk of loss transfer. This requires regularly conducting a stress test on it. Through this stress test, any expected or transferable loss arising from real estate shadow banking should be measured, depending on situations where property prices plummet below a certain level or market interest rates are on a sharp rise. And the amount in proportion to the loss incurred should be put aside as loss reserves. It is also notable that non-bank financial institutions could increase their exposure to high-risk real estate shadow banking to maximize short-term carried interest. Hence, it is worth considering overhauling the carried interest payment system.

1) Real estate collateral trusts provided by banks are excluded from shadow banking statistics.

2) See FSB, BIS, 2009, Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Considerations.

3) See FSB, 2022, Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2022.

Shadow banking is growing rapidly in Korea’s real estate market. It is a term used to describe non-bank financial institutions that engage in services similar to those of traditional banks but fall outside the realm of normal regulated banking, or financial investment instruments provided by such institutions. This article defines as real estate shadow banking the financial instruments provided by financing or credit intermediaries by means of real estate, including project financing (PF) loans and guarantees, PF asset-backed securities (PF-ABS), real estate trusts,1) real estate funds and special asset funds. In Korea, real estate shadow banking is worth KRW 876 trillion as of end-September 2022, representing a 3.6-fold increase from KRW 246 trillion at the end of 2014 and the average annual growth of 17.8% (Figure 1). Given an average annual increase of 7.8% in the loan balance of commercial banks during the same period, shadow banking in Korea’s real estate market has grown almost 2.5 times faster than general banks’ indirect financing. By type, real estate funds, special asset funds and PF-ABS have experienced a four- or five-fold rise while real estate trusts and PF loans and guarantees have tripled or quadrupled. This suggests that compared to banks’ indirect financing, all types of real estate shadow banking have expanded at a faster pace.

Risk assessment for real estate shadow banking

When selecting major financial institutions or measuring systemic risk levels within a financial system, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) usually consider size, interrelation, complexity and factors specific to a country.2) In terms of the four aspects mentioned above, Korea’s real estate shadow banking is experiencing a rapid increase in risk levels, which likely triggers systemic risk.

First, the proportion of real estate shadow banking in the Korean economy is rapidly increasing. Real estate shadow banking was responsible for only 16% of Korea’s GDP at the end of 2014 but swelled to 42% as of end-September 2022, taking up almost half of the GDP (Figure 2). It has increasingly accounted for a greater share in terms of the total value of Korea’s shadow banking. According to Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation published by the FSB,3) Korea’s real estate shadow banking was estimated at KRW 621 trillion at the end of 2014, of which real estate shadow banking was responsible for around 40%. At the end of 2021, the share of real estate shadow banking in the entire shadow banking sector surged rapidly to 62%. As for shadow banking, the ratio of real estate to the total excluding the real estate sector soared to 1.9 from 0.7 during the same period. It should be noted that real estate shadow banking has a close relation to assets and liabilities held by financial institutions, construction firms and households and shows high sensitivity to property prices. For these reasons, its fast-paced growth beyond a certain range should be viewed as a signal for greater systemic risk. If property prices plunge and consequently, real estate shadow banking intermediaries face the risk of insolvency, losses could be swiftly transmitted to other financial institutions or construction firms. The resultant fire-sale of real estate holdings may cause a sharper drop in property prices, thereby creating a vicious circle.

Third, Korea’s real estate shadow banking entails a high level of complexity and thus, could exacerbate systemic risk in the event of any insolvency event. As for real estate PF loans and debt guarantees, the risk of underlying assets is restructured through a credit and maturity adjustment and excessive leverage is used via some channels. For instance, a real estate PF contractor can make a division between equity-based PF and debt-based PF for financing. Debt-based PF is classified into senior, mid-risk and subordinated categories through structuring and is used to raise funds from numerous retail and institutional investors through a credit adjustment. Real estate PF-ABS allows investors to adjust maturities. A real estate PF business entity needs about three years to complete the sale of building units and usually issues a three-month PF-ABCP or PF-ABSTB for financing, which likely exposes it to maturity mismatches. If the issuance of PF-ABS hits a snag at least once during the three-year period, a relevant financial institution or construction firm could suffer huge losses in the real estate PF stage. As for PF debt guarantees by securities firms and warranted completion by real estate trusts, performance obligation arising from insolvency conditions is intricately described and the terms of a contract are not standardized. Furthermore, real estate funds and special asset funds also enable credit and maturity adjustments and have risks related to counterparties, exchange rate fluctuations and liquidity. This implies that real estate shadow banking is exposed to greater complexity as a whole.

Fourth, small- and medium-sized non-bank financial institutions are more likely to engage in high-risk real estate shadow banking. PF loans and debt guarantees fall into the category of high-risk real estate shadow banking. Notably, small-to-medium-size securities firms and specialized credit finance business entities—low in equity value and less capable of managing risks—have increased their exposure to PF loans and debt guarantees. This article analyzes 22 securities firms that extended bridge loans and provided debt guarantees to real estate PF as of end-September 2022. In terms of the ratio of equity to PF exposure, those with a smaller amount of equity show a tendency of having higher exposure to PF (Figure 3) within statistically significant levels (Figure 3). In PF loans and debt guarantees, higher fees are commonly charged and a lower amount of risk-weighted assets is reflected in the net capital ratio. This may explain why small-to-medium-size financial institutions have expanded PF loans and debt guarantees. If such firms that are less capable of dealing with risks increase their exposure to PF, it could have a negative knock-on effect on the financial health of other institutions when real estate shadow banking becomes fragile, which requires extra caution.

In short, real estate shadow banking in Korea has achieved rapid growth, represents a bigger presence relative to the size of its economy, is highly interconnected with the capital market, and entails greater complexity. Among non-bank financial institutions, small-to-medium-size ones are more likely to provide real estate shadow banking services. This means that a sharp drop in property prices may trigger insolvency in the entire real estate shadow banking sector. In terms of size, interrelation, complexity and Korea-specific factors, the chances are that real estate shadow banking will be more vulnerable to systemic risk in Korea.

Shadow banking can play a positive role in supplying venture capital as a substitute for the traditional banking system. But its excessive growth could bring about systemic risk. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, international financial supervisory authorities presented risk management strategies for shadow banking including curbing the growth pace of shadow banking, strengthening information transparency criteria and adopting regular stress tests. In line with such regulatory measures, Korea’s financial authorities should reinforce regulations and oversight to prevent real estate shadow banking from threatening financial stability.

First of all, prudential regulations should be tightened for non-bank financial services firms to hinder the fast-paced growth of loans and debt guarantees for real estate PF, real estate trusts for warranted construction completion, and PF-ABS, all of which are complex, high-leverage financial vehicles intertwined with the capital market. The formula for risk-weighted assets reflected in the net capital ratio needs to be modified while the calculation of the leverage ratio and the liquidity ratio should be improved. On top of that, it is necessary to step up monitoring of each risk factor in the entire real estate shadow banking sector, aiming for identifying the possibility of insolvency and the risk of loss transfer. This requires regularly conducting a stress test on it. Through this stress test, any expected or transferable loss arising from real estate shadow banking should be measured, depending on situations where property prices plummet below a certain level or market interest rates are on a sharp rise. And the amount in proportion to the loss incurred should be put aside as loss reserves. It is also notable that non-bank financial institutions could increase their exposure to high-risk real estate shadow banking to maximize short-term carried interest. Hence, it is worth considering overhauling the carried interest payment system.

1) Real estate collateral trusts provided by banks are excluded from shadow banking statistics.

2) See FSB, BIS, 2009, Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Considerations.

3) See FSB, 2022, Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2022.