Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Analysis of IPO Underpricing Factors and Implications

Publication date Mar. 05, 2024

Summary

IPO underpricing is often seen as a compensation mechanism to mitigate information asymmetry and prevent IPO failures. However, it should be noted that if the fair value of a company is not adequately reflected in the offer price, it can lead to higher financing costs for newly listed companies. In an analysis of IPO underpricing by country, Korea stands out for experiencing the most significant underpricing in its IPO market among other comparable countries, a trend that has persisted even allowing for temporal fluctuations and information effects. This phenomenon can be partly attributed to changes in the profile of newly listed companies, particularly increased listing of companies with substantial information asymmetry. In addition, inefficiencies in the IPO pricing process have likely contributed to this phenomenon.

Upon closer examination of the IPO underpricing sample, the discount rate for the indicative offer price relative to the reference price, as assessed by underwriters, is slightly higher for underpriced companies. Additionally, the reference price is set substantially lower than the actual market value. Furthermore, although the demand exceeding the indicative price band is clearly observed in the bookbuilding process in the case of underpriced companies, this seems not to be fully reflected in the final offer price. These findings suggest that underwriters’ valuation of newly listed companies may lack the flexibility to align with market conditions or corporate characteristics. They also indicate that current market practices or regulatory frameworks may hinder underwriters from exercising their discretion in determining the final offer price. Considering the direct link between the maturity of the IPO market and the competitiveness of capital markets, there is a need for improvements in regulations and practices within the IPO market.

Upon closer examination of the IPO underpricing sample, the discount rate for the indicative offer price relative to the reference price, as assessed by underwriters, is slightly higher for underpriced companies. Additionally, the reference price is set substantially lower than the actual market value. Furthermore, although the demand exceeding the indicative price band is clearly observed in the bookbuilding process in the case of underpriced companies, this seems not to be fully reflected in the final offer price. These findings suggest that underwriters’ valuation of newly listed companies may lack the flexibility to align with market conditions or corporate characteristics. They also indicate that current market practices or regulatory frameworks may hinder underwriters from exercising their discretion in determining the final offer price. Considering the direct link between the maturity of the IPO market and the competitiveness of capital markets, there is a need for improvements in regulations and practices within the IPO market.

An initial public offering (IPO) typically refers to a process where a company discloses information to the public for the first time, raises capital at an appropriate price, and lists its shares on a stock exchange. This process serves as a means for companies to secure funds for innovation and growth and enhance asset liquidity and transparency, while creating new investment opportunities for retail investors. As IPOs are the primary means of intermediating funds between retail investors and companies, the fundamental function of capital markets, the efficiency of the IPO market is crucial for the competitiveness of capital markets.

In light of this view, this article analyzes the efficiency of the IPO market in Korea, focusing on IPO underpricing, and presents relevant implications. To this end, it provides an overview of the current state of IPO underpricing and offers a range of analytical findings.

Current state of IPO underpricing in Korea

IPO underpricing is a well-known phenomenon in the IPO market, as evidenced by both domestic and international academic research. Various theories1) have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, all of which suggest that the offer price is set low to compensate for information asymmetry and attract investors (Beatty & Ritter, 1986). This practice can be rationalized as a mechanism to prevent market failures resulting from information asymmetry. However, it should be noted that if the fair value of a company is not adequately reflected in the offer price, it could increase the financing costs for the company. Therefore, accurate valuation of newly listed companies and appropriate pricing of IPOs are crucial factors in the IPO process.

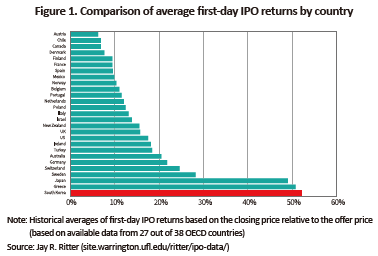

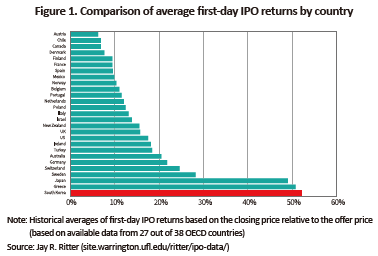

In an analysis of IPO underpricing by country, Korea has historically experienced the most significant IPO underpricing. Figure 1 shows the average first-day IPO returns across OECD member countries. Despite variations in the analysis period for each country,2) Korea’s first-day IPO return, measured based on the closing price relative to the offer price, averages 52%, the highest among OECD countries.3) This suggests that in terms of IPO underpricing, Korea’s IPO market efficiency is relatively low compared to other countries.

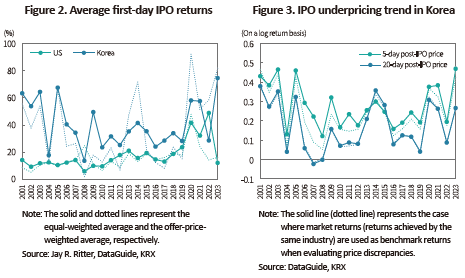

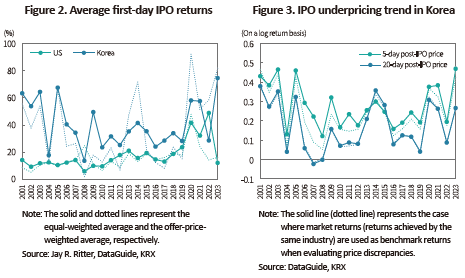

However, it is noteworthy that IPO underpricing levels may vary by period (Lowry et al., 2010) and first-day IPO returns can be affected by investor sentiment and trading behaviors (Aissia, 2014), which necessitates adjustments for these factors. Figure 2 illustrates first-day IPO returns relative to the offer price for newly listed stocks in both the Korean and US markets over the years. In the US, the average first-day IPO return saw a surge amid an IPO market boom following the Covid-19 pandemic, while historically, its average market price relative to the offer price was lower than that of Korea, except in 2022. Given the significant price volatility during the early listing stages, it is rational to compare the offer price to the five-day (or 20-day) post-IPO closing price, not the market price on the listing day, after the offer price is determined. Figure 3 presents the IPO underpricing adjusted for benchmark returns, measured annually, mitigating the information effect after the offer price is fixed.4) As depicted, a substantial discrepancy between the offer price and the market price is observed, albeit with temporal fluctuations. It is also notable that except for specific periods such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the average offer price tends to be undervalued compared to the fair market price. Among various factors behind this phenomenon, this article primarily focuses on the profile of newly listed companies and the IPO pricing process.

IPO underpricing factors: ① Characteristics of newly listed companies

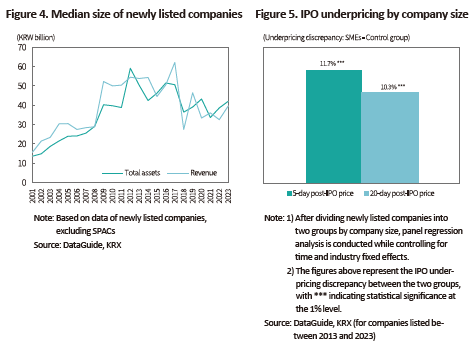

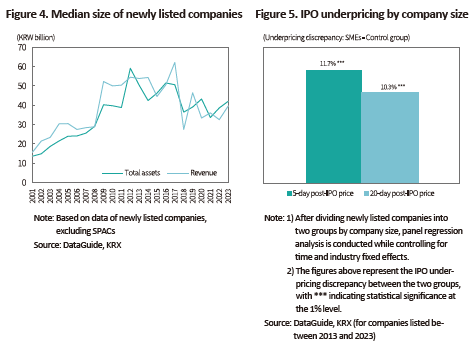

First, it is worth considering the characteristics of newly listed companies. Although the capabilities and discretion of underwriters have increased as the IPO market reaches maturity, setting an appropriate offer price may be challenging if there is a significant proportion of newly listed companies with substantial information asymmetry. Figure 4 shows the median values of total assets and revenue of newly listed companies as of the end of the fiscal year prior to listing.5) The median size of newly listed companies experienced a steady rise from the 2000s to the mid-2010s before declining thereafter. Since the mid-2010s, there has been an increase in the number of IPOs by companies with small asset sizes or revenue figures, which can be attributed to the relaxation of listing requirements by stock exchanges and the expansion of the special listing system. As stock exchanges have lowered barriers to listing to promote the entry of innovative companies, this has facilitated the participation of companies with growth potential and technological prowess in the IPO market, despite their limited financial performance.6)

To briefly examine the relationship between information asymmetry and IPO underpricing, this article divides newly listed companies into two groups based on total asset size and calculates the average level of IPO underpricing for each group. Using the methodology from Figure 3, IPO underpricing is estimated by comparing the offer price to the stock price recorded five and 20 days following IPOs. This comparison focuses on the sample of companies listed since 2013,7) as shown in Figure 5. The figures in the graph indicate the difference in IPO underpricing levels between small-sized listed companies with total assets below KRW 30 billion and the control group. The analysis finds that the average underpricing level for SMEs is around 10.3% to 11.7% higher than that of the control group, which is statistically significant. If company size is a measure of information asymmetry, IPO underpricing can be interpreted as being affected by information asymmetry. This suggests that the persistent underpricing in the Korean IPO market can stem partially from changes in the composition of newly listed companies as well as the relaxation of listing requirements.

IPO underpricing factors: ② IPO pricing process

While the first factor contributing to IPO underpricing has been examined from the company perspective, the second factor pertains to the efficiency of underwriters’ IPO pricing for newly listed companies. Despite minor and major regulatory changes and policies aimed at expanding underwriters’ discretion, the Korean IPO market has been heavily affected by regulatory authorities in terms of specific disclosure regulations, price range restrictions, participants and allocation regulations for bookbuilding, and legal liabilities. It has also led to a lack of autonomy and accountability among market participants (Kim et al., 2016). A lead manager determines the final offer price through due diligence evaluation and bookbuilding, during which the IPO pricing process encompassing the reference price, the indicative offer price, and ultimately, the final offer price can be identified, relying on the disclosure information provided by an underwriter. To enhance comparability in this analysis, a sample of IPO underpricing is defined8) and the defined sample is compared to the control group to assess the efficiency of IPO pricing.

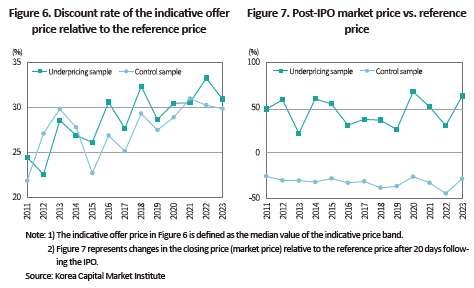

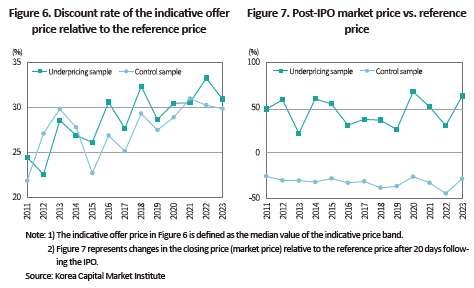

First, it is necessary to examine how an underwriter establishes the reference price and indicative offer price. The underwriter assesses corporate value through due diligence and other procedures to determine the reference price. Figure 6 illustrates how much the indicative offer price is discounted relative to the reference rate by year. Since the start of the analysis period,9) the average discount rate relative to the reference price has generally increased, particularly evident in the sample with significant underpricing, reaching a peak discount rate difference of around 2% to 3%. In addition, when the underwriter’s reference price is compared to the post-IPO market price, the underwriter tends to evaluate the reference price considerably lower in the underpricing sample. Figure 7 demonstrates that in the underpricing sample, the stock price after 20 days of listing exceeds the reference price by approximately 20% to 50%. Conversely, in the sample without underpricing, the reference price is set even higher.

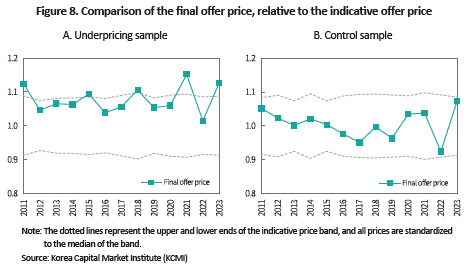

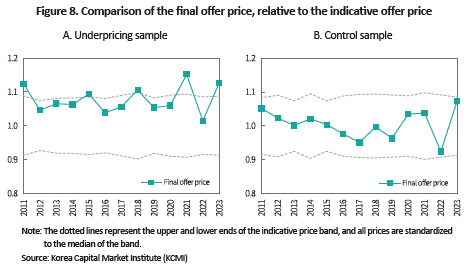

As the next step, the two samples are compared to find out how the final offer price is determined through bookbuilding after the indicative price band is presented. Figure 8 illustrates the average indicative price band and final offer price by year. The indicative price band typically spans from the upper 10% to the lower 10% based on the median. In the underpricing sample, the final offer price tends to be predominantly set at or near the upper end of the band, in contrast to the control sample where the final offer price is primarily determined within the band.

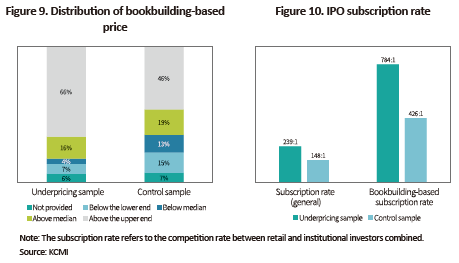

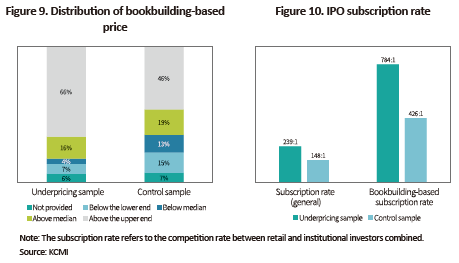

Figure 9 summarizes the demand distribution for the underpricing sample and control sample across price intervals derived from bookbuilding. In the underpricing sample, around 66% of the demand goes beyond the upper end of the indicative price band. This is also evident in the IPO oversubscription rate. IPOs in the underpricing sample are oversubscribed by 784 times, higher than the control sample’s oversubscription of 239 times (Figure 10). Taken together with Figure 8, it suggests that in the case of the underpricing sample, the final offer price tends to be set restrictively at the upper end or within the indicative price band, despite the demand from actual bidders exceeding the band and the demand itself remaining high.

The analysis results above can be summarized as follows, with a focus on the IPO underpricing sample. Firstly, in the case of underpriced newly listed companies, the reference price is set lower than their actual market price, and the discount rate applied to the indicative offer price is also relatively higher. Furthermore, the demand exceeding the indicative price band is observed during the bookbuilding process, which, however, is not adequately reflected in the final offer price.

Conclusion

The Korean IPO market has undergone regulatory changes since the 2007 deregulation of underwriting activities, aligning its regulatory framework with that of advanced economies. Despite this outward improvement, the IPO market, characterized by underpricing, has proven less efficient. The analysis of IPO underpricing factors in Korea reveals that changes in the characteristics of newly listed companies, coupled with limited underwriters’ discretion, have contributed to the IPO underpricing phenomenon where market demand is not fully reflected in the offer price. These findings suggest two potential scenarios: first, underwriters’ valuation of newly listed companies may not flexibly consider market conditions or corporate characteristics; second, despite regulatory provisions allowing for greater underwriter discretion, there seems to be a practice of setting the final offer price within the indicative price band.

If this situation persists, IPO underpricing will drive up the financing costs for newly listed companies, resulting in unnecessary wealth transfers. Considering that the maturity of the IPO market is directly related to the competitiveness of capital markets, there is a need for improvement in both regulations and practices within the IPO market. Moreover, as in the IPO process, underwriters play a pivotal role in mitigating information asymmetry and facilitating interactions between companies and retail investors, it is essential to enhance the autonomy and accountability of underwriters. Additionally, a regulatory framework should be established to foster the growth of underwriters.

1) Previous studies suggest that various factors come into play in IPO underpricing, including information asymmetry (Beatty & Ritter, 1986), market conditions created by lead managers (Ruud, 1993), corporate governance and agency costs (Brennan & Franks, 1997), and behavioral patterns of investors or issuers (Loughran & Ritter, 2002; Ljungqvist et al., 2006).

2) In the case of Korea, the analysis period spans from 1980 to 2022, while the analysis period for most other countries also ranges from the early 1980s to the present. As for advanced economies such as the US, the UK, Canada, Japan, and Australia, periods even before the 1980s are included for analysis.

3) Compared to countries outside the OECD, Korea shows the highest first-day IPO return on average, following China, India, and Middle Eastern countries such as Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

4) The IPO underpricing is calculated by subtracting the benchmark log return , measured up to a specific trading day after the offer price is fixed, from the log return based on the offer price

, measured up to a specific trading day after the offer price is fixed, from the log return based on the offer price  relative to the closing price achieved after T trading days following listing

relative to the closing price achieved after T trading days following listing  :

:

5) As the average is significantly influenced by large-scale IPOs, the statistical average is set as the median value.

5) As the average is significantly influenced by large-scale IPOs, the statistical average is set as the median value.

6) Since the introduction of the special listing system for technology companies in 2005, the listing requirements for the KOSDAQ market have been relaxed, such as listing regulations for those with growth potential or without realized profit. As a result, more than 50% of newly listed companies have entered the IPO market by meeting these relaxed requirements.

7) The sample period is set from 2013 onwards because it is the period characterized by changes in the profile of newly listed companies, such as the decline in the average size of newly listed companies and the increase in companies eligible for special listing systems.

8) Based on the methodology from Figures 3 and 5, the IPO underpricing sample is defined as having an underpricing indicator (controlled for industry returns) of over 0.2. Exceeding 0.2 (based on log returns) indicates that the offer price is roughly 22% undervalued relative to the fair market value. Changing the criteria for the sample hardly yields any qualitative difference in the results.

9) The analysis period is set as starting from 2011 due to the lack of reference price data in disclosure documents of IPOs released until August 2010, following the deregulation of underwriting activities in June 2007. Amid controversies over inflated IPO prices during the IPO boom in 2010, relevant authorities imposed stricter regulations on disclosure and pricing.

References

Aissia, D.B., 2014, IPO first-day returns: Skewness preference, investor sentiment and uncertainty underlying factors, Review of Financial Economics 23(3), 148-154.

Beatty, R.P., Ritter, J.R., 1986, Investment banking, reputation, and the underpricing of initial public offerings, Journal of Financial Economics 15(1-2), 213-232.

Brennan, M.J., Franks, J., 1997, Underpricing, ownership and control in initial public offerings of equity securities in the UK, Journal of Financial Economics 45(3), 391-413.

Ljungqvist, A., Nanda, V., Singh, R., 2006, Hot markets, investor sentiment, and IPO pricing, Journal of Business 79(4), 1667-1702.

Loughran, T., Ritter, J.R. (2002, Why don’t issuers get upset about leaving money on the table in IPOs?, Review of Financial Studies 15(2), 413-444.

Lowry, M., Officer, M.S., Schwert, G. W., 2010, The variability of IPO initial returns, Journal of Finance 65(2), 425-465.

Ruud, J.S., 1993, Underwriter price support and the IPO underpricing puzzle, Journal of Financial Economics 34(2), 135-151.

[Korean]

Kim, K.L, Kim, J.S., Lee, S.H. and Shin, I.S., 2016, Analysis of the IPO market structure in Korea, KCMI Research Series 16-02.

Lee, S.H., 2021, Recent growth of retail investors in the IPO market and bookbuilding process, KCMI Issue Paper 21-14.

In light of this view, this article analyzes the efficiency of the IPO market in Korea, focusing on IPO underpricing, and presents relevant implications. To this end, it provides an overview of the current state of IPO underpricing and offers a range of analytical findings.

Current state of IPO underpricing in Korea

IPO underpricing is a well-known phenomenon in the IPO market, as evidenced by both domestic and international academic research. Various theories1) have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, all of which suggest that the offer price is set low to compensate for information asymmetry and attract investors (Beatty & Ritter, 1986). This practice can be rationalized as a mechanism to prevent market failures resulting from information asymmetry. However, it should be noted that if the fair value of a company is not adequately reflected in the offer price, it could increase the financing costs for the company. Therefore, accurate valuation of newly listed companies and appropriate pricing of IPOs are crucial factors in the IPO process.

In an analysis of IPO underpricing by country, Korea has historically experienced the most significant IPO underpricing. Figure 1 shows the average first-day IPO returns across OECD member countries. Despite variations in the analysis period for each country,2) Korea’s first-day IPO return, measured based on the closing price relative to the offer price, averages 52%, the highest among OECD countries.3) This suggests that in terms of IPO underpricing, Korea’s IPO market efficiency is relatively low compared to other countries.

First, it is worth considering the characteristics of newly listed companies. Although the capabilities and discretion of underwriters have increased as the IPO market reaches maturity, setting an appropriate offer price may be challenging if there is a significant proportion of newly listed companies with substantial information asymmetry. Figure 4 shows the median values of total assets and revenue of newly listed companies as of the end of the fiscal year prior to listing.5) The median size of newly listed companies experienced a steady rise from the 2000s to the mid-2010s before declining thereafter. Since the mid-2010s, there has been an increase in the number of IPOs by companies with small asset sizes or revenue figures, which can be attributed to the relaxation of listing requirements by stock exchanges and the expansion of the special listing system. As stock exchanges have lowered barriers to listing to promote the entry of innovative companies, this has facilitated the participation of companies with growth potential and technological prowess in the IPO market, despite their limited financial performance.6)

IPO underpricing factors: ② IPO pricing process

While the first factor contributing to IPO underpricing has been examined from the company perspective, the second factor pertains to the efficiency of underwriters’ IPO pricing for newly listed companies. Despite minor and major regulatory changes and policies aimed at expanding underwriters’ discretion, the Korean IPO market has been heavily affected by regulatory authorities in terms of specific disclosure regulations, price range restrictions, participants and allocation regulations for bookbuilding, and legal liabilities. It has also led to a lack of autonomy and accountability among market participants (Kim et al., 2016). A lead manager determines the final offer price through due diligence evaluation and bookbuilding, during which the IPO pricing process encompassing the reference price, the indicative offer price, and ultimately, the final offer price can be identified, relying on the disclosure information provided by an underwriter. To enhance comparability in this analysis, a sample of IPO underpricing is defined8) and the defined sample is compared to the control group to assess the efficiency of IPO pricing.

As the next step, the two samples are compared to find out how the final offer price is determined through bookbuilding after the indicative price band is presented. Figure 8 illustrates the average indicative price band and final offer price by year. The indicative price band typically spans from the upper 10% to the lower 10% based on the median. In the underpricing sample, the final offer price tends to be predominantly set at or near the upper end of the band, in contrast to the control sample where the final offer price is primarily determined within the band.

The analysis results above can be summarized as follows, with a focus on the IPO underpricing sample. Firstly, in the case of underpriced newly listed companies, the reference price is set lower than their actual market price, and the discount rate applied to the indicative offer price is also relatively higher. Furthermore, the demand exceeding the indicative price band is observed during the bookbuilding process, which, however, is not adequately reflected in the final offer price.

The Korean IPO market has undergone regulatory changes since the 2007 deregulation of underwriting activities, aligning its regulatory framework with that of advanced economies. Despite this outward improvement, the IPO market, characterized by underpricing, has proven less efficient. The analysis of IPO underpricing factors in Korea reveals that changes in the characteristics of newly listed companies, coupled with limited underwriters’ discretion, have contributed to the IPO underpricing phenomenon where market demand is not fully reflected in the offer price. These findings suggest two potential scenarios: first, underwriters’ valuation of newly listed companies may not flexibly consider market conditions or corporate characteristics; second, despite regulatory provisions allowing for greater underwriter discretion, there seems to be a practice of setting the final offer price within the indicative price band.

If this situation persists, IPO underpricing will drive up the financing costs for newly listed companies, resulting in unnecessary wealth transfers. Considering that the maturity of the IPO market is directly related to the competitiveness of capital markets, there is a need for improvement in both regulations and practices within the IPO market. Moreover, as in the IPO process, underwriters play a pivotal role in mitigating information asymmetry and facilitating interactions between companies and retail investors, it is essential to enhance the autonomy and accountability of underwriters. Additionally, a regulatory framework should be established to foster the growth of underwriters.

1) Previous studies suggest that various factors come into play in IPO underpricing, including information asymmetry (Beatty & Ritter, 1986), market conditions created by lead managers (Ruud, 1993), corporate governance and agency costs (Brennan & Franks, 1997), and behavioral patterns of investors or issuers (Loughran & Ritter, 2002; Ljungqvist et al., 2006).

2) In the case of Korea, the analysis period spans from 1980 to 2022, while the analysis period for most other countries also ranges from the early 1980s to the present. As for advanced economies such as the US, the UK, Canada, Japan, and Australia, periods even before the 1980s are included for analysis.

3) Compared to countries outside the OECD, Korea shows the highest first-day IPO return on average, following China, India, and Middle Eastern countries such as Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

4) The IPO underpricing is calculated by subtracting the benchmark log return

6) Since the introduction of the special listing system for technology companies in 2005, the listing requirements for the KOSDAQ market have been relaxed, such as listing regulations for those with growth potential or without realized profit. As a result, more than 50% of newly listed companies have entered the IPO market by meeting these relaxed requirements.

7) The sample period is set from 2013 onwards because it is the period characterized by changes in the profile of newly listed companies, such as the decline in the average size of newly listed companies and the increase in companies eligible for special listing systems.

8) Based on the methodology from Figures 3 and 5, the IPO underpricing sample is defined as having an underpricing indicator (controlled for industry returns) of over 0.2. Exceeding 0.2 (based on log returns) indicates that the offer price is roughly 22% undervalued relative to the fair market value. Changing the criteria for the sample hardly yields any qualitative difference in the results.

9) The analysis period is set as starting from 2011 due to the lack of reference price data in disclosure documents of IPOs released until August 2010, following the deregulation of underwriting activities in June 2007. Amid controversies over inflated IPO prices during the IPO boom in 2010, relevant authorities imposed stricter regulations on disclosure and pricing.

References

Aissia, D.B., 2014, IPO first-day returns: Skewness preference, investor sentiment and uncertainty underlying factors, Review of Financial Economics 23(3), 148-154.

Beatty, R.P., Ritter, J.R., 1986, Investment banking, reputation, and the underpricing of initial public offerings, Journal of Financial Economics 15(1-2), 213-232.

Brennan, M.J., Franks, J., 1997, Underpricing, ownership and control in initial public offerings of equity securities in the UK, Journal of Financial Economics 45(3), 391-413.

Ljungqvist, A., Nanda, V., Singh, R., 2006, Hot markets, investor sentiment, and IPO pricing, Journal of Business 79(4), 1667-1702.

Loughran, T., Ritter, J.R. (2002, Why don’t issuers get upset about leaving money on the table in IPOs?, Review of Financial Studies 15(2), 413-444.

Lowry, M., Officer, M.S., Schwert, G. W., 2010, The variability of IPO initial returns, Journal of Finance 65(2), 425-465.

Ruud, J.S., 1993, Underwriter price support and the IPO underpricing puzzle, Journal of Financial Economics 34(2), 135-151.

[Korean]

Kim, K.L, Kim, J.S., Lee, S.H. and Shin, I.S., 2016, Analysis of the IPO market structure in Korea, KCMI Research Series 16-02.

Lee, S.H., 2021, Recent growth of retail investors in the IPO market and bookbuilding process, KCMI Issue Paper 21-14.