OPINION

2023 Aug/22

Low-carbon Portfolios and Capital Market Responses to Climate Change

Aug. 22, 2023

PDF

- Summary

- Amidst the trend of strengthening greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction regulations, climate risks are expected to gradually become a significant risk factor that investors should consider. Although there has not yet been a clear academic consensus on the impact of climate risk, there is a possibility that industries and companies with large GHG emissions are exposed to transition risks due to future carbon price increases. Therefore, long-term investors need to manage the climate risk of their portfolio, and it is urgent to activate low-carbon investment for facilitating capital market-driven incentives for carbon neutrality in the industrial sector in the mid- to long-run.

Discussions and research have continued on low-carbon portfolio investment strategies for achieving net-zero internationally. This has resulted in the launch of various forms of decarbonized indices, and more adoption of related financial instruments and new types of benchmarks. In Europe, the EU Climate Benchmarks were announced to define the minimum criteria for decarbonized indices. Large institutional investors such as overseas pension funds are investing equity inflows into low-carbon portfolios. On the other hand, South Korea is taking a passive stance in terms of climate change. There is a need to enhance the awareness of capital market participants for addressing future climate risks and to activate low-carbon investments.

Necessity of responding to climate change from investors' point of view

As pan-national regulations on GHG reduction have been strengthened sine the 2015 Paris Agreement, climate risk is expected to become a significant risk factor for investors to consider. Climate risk can be understood as both physical risks resulting from climate change itself, as well as transition risks that may arise from carbon price increases or tougher regulation during the transition to a low-carbon economy. Since climate risks involve the long-run nature with uncertain future scenarios and economic costs, it is important to recognize and respond to them from an investor's point of view.

However, there has been no consensus on the impact of climate risks on asset prices thus far. For example, there are mixed empirical results on the relationship between carbon risks measured by carbon emissions and expected stock returns depending on the methodology (Bolton & Kacperczyk, 2021; Aswani et al., 2023; Zhang, 2023). Also, funds or indices focusing on industries and companies that are relatively less exposed to climate risk have underperformed than expected (Ibikunle & Steffen, 2017; Naqvi et al., 2021). Of course, these results may have been influenced by factors such as the absence of standardized data for objectively measuring climate risk and the presence of greenwashing, which is a form of disguised environmentalism. However, it would be hard to think that prices formed in the capital market have effectively reflected the climate risk of assets, at least to this point.

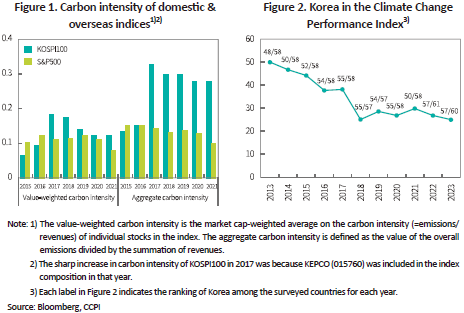

Nevertheless, from the perspective of domestic investors in Korea, there are two main reasons why responses to climate change are necessary in the future. First, industries or companies that currently heavy emitters of GHGs can be highly exposed to transition risks such as carbon price increases in the near future. Especially, Korean companies have formed an export-oriented and carbon-intensive industrial structure, so GHG reduction regulations aimed at carbon neutrality may lead to increased production and sales costs, lower profits, and declined asset value in the long run. Figure 1 illustrates the trend of portfolio-level carbon intensity for the KOSPI100 index including major domestic large-cap stocks and the S&P500 index set as the comparison group.1) As can be seen in Figure 1, the overall carbon intensity of the Korean stock market–that is, climate risk–is higher than that of developed markets. Hence, it is necessary to manage climate risk from a stock portfolio perspective.

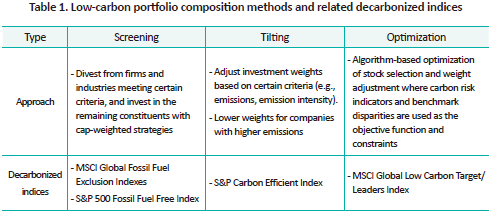

Secondly, if a sufficient number of investors adjust their portfolios to align with carbon-neutral objectives for climate change mitigation, this could function as a long-term incentive for GHG reduction in various industries. There have been stronger efforts to induce the industrial sector to move towards carbon neutrality via the financial sector, with the heavier emphasis on the role and importance of climate finance. Accordingly, a large number of global investors and asset managers have declared their net zero initiative and established related roadmap (Song, 2022). Figure 2 summarizes Korea's climate change response score and ranking among 60 countries in the Climate Change Performance Index2) released by Germanwatch, an international climate assessment institution in Germany. South Korea is found in the bottom ranks, indicating the urgent need for efforts to address the climate crisis. Since the transition to a low-carbon economy is no longer an option but a necessity, Korea needs to strengthen the emissions trading system currently in effect, and provide capital market-based incentives to respond to climate change.

Discussion on how to invest in low-carbon portfolios

Thus far, academia and industry have emphasized awareness of climate risks and the need for risk management (Andersson et al., 2016). More recently, long-term investment approaches aligned with pathways to achieve net-zero have been proposed (Bolton et al., 2022). There are three key considerations when summarizing the discussion and research on the methodology of building a portfolio (or index) that can provide an incentive to reduce GHG emissions while hedging climate risks to some extent.

Firstly, there should be a meaningful reduction in carbon footprint compared to the benchmark. The weighted average carbon intensity is primarily used as a measure of portfolio-level carbon footprint.3) The proxy for carbon risks in a low-carbon portfolio should be significantly lower than that of the benchmark. Secondly, a low-carbon portfolio should track the parent index to some extent and maintain a similar level of risk exposure to that of the parent index. While building a portfolio centered around assets related to renewable energy and eco-friendly services could be considered to mitigate carbon risks in another way, this approach has a very limited scalability in terms of investment scope. Hence, it may not be suitable for large institutional investors' portfolios. Therefore, a method is needed to reduce the carbon footprint of the portfolio while minimizing tracking errors with the parent index. Finally, the risk of greenwashing should be minimized. It is important to consider investments in sectors that need decarbonization with reliable transition plans, rather than solely focusing on companies with lower emissions. This is because investors' continued engagement with companies is essential to providing the companies an incentive for achieving the long-term net-zero goal.

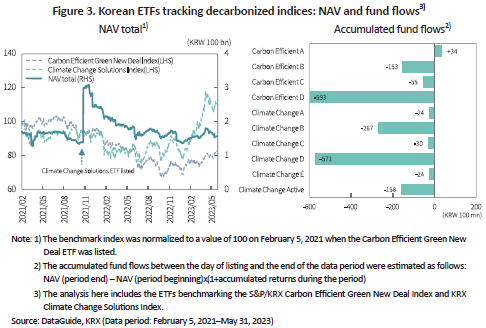

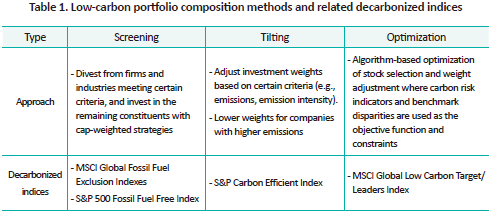

Table 1 sums up various methodologies for building low-carbon portfolios. It is worth evaluating each one of them based on the considerations mentioned above. Firstly, the screening method tries to exclude companies or industries that meet certain criteria. For example, portfolios that do not invest in companies with high fossil fuel revenue shares (e.g., MSCI/S&P Fossil Fuel Free Index) fall under this category. Screening has the advantages of being easy to understand and suitable for performance comparison. However, the drawback is that divestment may make it difficult to engage with companies that require transition and could lead to tracking errors against the parent index. On the other hand, tilting is a method of rebalancing investment based on carbon risk indicators (e.g., the S&P Carbon Efficient index). This is said to be more sustainable than the screening method in that it can provide incentives for decarbonization through continuous investment. However, the downside is that the disparity with the benchmark could widen depending on how to adjust weights. Finally, the algorithm-based optimization method can estimate an optimized portfolio that satisfies the desired level of carbon footprint abatement and disparity reduction if the objective function and constraints are set properly. This is by far the most widely used method in the MSCI Global Low Carbon Target/Leaders Index, and other recently emerging decarbonized indices. Not only does it maintain exposure levels to various risk factors similar to the parent index, but it also minimizes divestment strategies for specific industries, allowing investors to consistently engage with companies. However, its black box-like structure is hard to understand compared to the above two methods, and optimization results can be distorted as the parameters become conservative.

Recently, Europe adopted new rules setting out the minimum technical requirements for climate transition benchmarks that institutional investors can refer to in order to provide guidelines for decarbonized indices, and revised the relevant EU benchmark regulations.4) These 'EU Climate Benchmarks' are classified into EU CTBs and PABs, defined as the requirements for the minimum reduction pathways to achieve the transition to a low-carbon economy based on scientific evidence from the IPCC. What they have in common is that both benchmarks follow a 7% year-on-year decarbonization path, but EU PABs require more stringent standards than EU CTBs.5) Global index providers including MSCI, S&P, and FTSE Russel have recently launched indices.6) They are designed to meet the EU climate benchmark requirements, and to minimize disparities with the parent index through optimization methodology.

Low-carbon portfolio investment and its implications

In overseas cases where ongoing discussions on investor responses to climate change and the methodology of building low-carbon portfolios have persistently taken place, the use of decarbonized indices has increased especially among large asset owners including pension funds. One notable example is AP4, the Swedish national pension fund, which introduced decarbonized indices at first. To hedge carbon risks in their global equity portfolio, AP4 set a new benchmark of the S&P 500 Carbon Efficient Select Index, which tracks the S&P 500 Index to some extent while reducing carbon risks. The index reportedly reduces carbon footprint by 50% compared to the parent index while keeping the disparity ratio under 0.5%. Furthermore, the French Reserve Fund worked together with AP4, MSCI, and Amundi to develop the MSCI Low Carbon Leaders Index series, applying the methodology of constructing low-carbon portfolios to continent-wide passive management. In addition, the New York State Common Retirement Fund, and the California State Teachers' Retirement System have allocated their investment in low-carbon portfolios by setting the FTSE Russell Climate Transition Index and the MSCI ACWI Low Carbon Target Index as a new benchmark, respectively. Moreover, it is observed that the investment landscape for low-carbon portfolios has expanded further as more ETFs tracking decarbonized indices have been consistently listed.

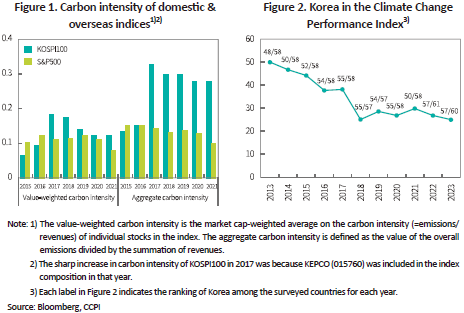

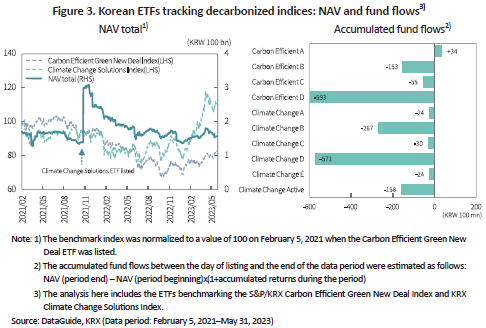

However, investment in low-carbon portfolios has been inactive in Korea. No asset owner in Korea has adopted decarbonized indices as a benchmark similar to overseas cases. Korea's National Pension Service (NPS) has not established concrete coal divestment policies since it declared a coal exit two years ago in May 2021. Although numerous ETFs benchmarking decarbonized indices have been listed since 20217), their net asset value has constantly declined, and net outflows have been observed in all ETFs except for one. This is partly due to a lack of interest from individual investors. But more importantly, the reason behind this is the de facto non-existent demand from institutional investors.

Clear implications can be found in the discussions on low-carbon investment methodologies as part of climate risk responses and the cases of leading index providers and institutional investors. While uncertainties remain, climate risks are likely to materialize in the near future, and South Korea is unlikely to be an exception. If a carbon risk is properly priced and climate risks are appropriately reflected in asset prices, there will be evident impact on investors and portfolios. Long-term investors should consider these climate risks as significant risk factors. Moreover, it is necessary to raise awareness of decarbonization investments and promote related investments in order to facilitate capital market responses to climate change.

1) The reason for limiting the sample to KOSPI100 is that the KOSPI200 sample had many missing values in the carbon emission data provided by Bloomberg.

2) Germanwatch, together with the NewClimate Institute, evaluated the level of climate policy and implementation in 60 countries and the European Union, which account for 90% of global GHG emissions. The result is released as the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) of each country.

3) The weighted average carbon intensity is defined as the exposure-weighted average carbon intensity (=GHG emissions/revenues) of individual companies. This is the most widely used in practice ever since this was approved by the 2017 TCFD recommendations due to its applicability to all asset classes and ease of intuitive understanding (Funk, 2020).

4) In February 2019, the European Parliament and member states agreed to create two types of decarbonization benchmarks: the EU Climate Transition Benchmark (EU CTB) and the EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark (EU PAB). In July 2020, the technical expert group (TEG) of the European Commission adopted new rules that set out minimal technical requirements for the methodology of EU climate benchmarks.

5) For example, the EU PAB demands a minimum of 50% reduction in carbon intensity compared to the parent index and divests from carbon-intensive energy (e.g., coal and oil) companies. On the other hand, the EU CTB has a lower target of 30% without any divestment activities.

6) The MSCI Climate Paris Aligned Indexes, MSCI Climate Change Indexes, S&P Paris-Aligned & Climate Transition index series including the S&P 500 Net Zero 2050 Paris-Aligned ESG Index fall under this category.

7) Notable examples include four KRX/S&P Carbon Efficient Green New Deal ETFs listed on February 5, 2021, and five KRX Climate Change Solution ETFs along with one active ETF listed on October 29, 2021. Both benchmark indices utilized the tilting method in selecting the constituents and computing their weights. Among these, the Carbon Efficient Green New Deal ETF is designed to track the performance of the parent index in the Korean stock market to some extent.

References

Andersson, M., Bolton, P., Samama, F., 2016, Hedging climate risk. Financial Analysts Journal 72(3), 13-32.

Aswani, J., Raghunandan, A., Rajgopal, S., 2023, Are carbon emissions associated with stock returns? Review of Finance, Forthcoming.

Bolton, P., Kacperczyk, M., 2021, Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics 142(2), 517-549.

Bolton, P., Kacperczyk, M., Samama, F., 2022, Net-zero carbon portfolio alignment. Financial Analysts Journal 78(2), 19-33.

Funk C.M., September 2020, Carbon Footprinting: An Investor Toolkit. State Street Global Advisors.

Ibikunle, G., Steffen, T., 2017, European green mutual fund performance: A comparative analysis with their conventional and black peers. Journal of Business Ethics 145, 337-355.

Naqvi, B., Mirza, N., Rizvi, S., Porada-Rochon, M., Itani, R., 2021, Is there a green fund premium? Evidence from twenty-seven emerging markets. Global Finance Journal 50, 100656.

Zhang, S., 2023, Carbon premium: Is it there? Working Paper.

[Korean]

Song, H.S., 2022, Aligning the capital market with the 2050 carbon net zero, KCMI Opinion 2022-02.

As pan-national regulations on GHG reduction have been strengthened sine the 2015 Paris Agreement, climate risk is expected to become a significant risk factor for investors to consider. Climate risk can be understood as both physical risks resulting from climate change itself, as well as transition risks that may arise from carbon price increases or tougher regulation during the transition to a low-carbon economy. Since climate risks involve the long-run nature with uncertain future scenarios and economic costs, it is important to recognize and respond to them from an investor's point of view.

However, there has been no consensus on the impact of climate risks on asset prices thus far. For example, there are mixed empirical results on the relationship between carbon risks measured by carbon emissions and expected stock returns depending on the methodology (Bolton & Kacperczyk, 2021; Aswani et al., 2023; Zhang, 2023). Also, funds or indices focusing on industries and companies that are relatively less exposed to climate risk have underperformed than expected (Ibikunle & Steffen, 2017; Naqvi et al., 2021). Of course, these results may have been influenced by factors such as the absence of standardized data for objectively measuring climate risk and the presence of greenwashing, which is a form of disguised environmentalism. However, it would be hard to think that prices formed in the capital market have effectively reflected the climate risk of assets, at least to this point.

Nevertheless, from the perspective of domestic investors in Korea, there are two main reasons why responses to climate change are necessary in the future. First, industries or companies that currently heavy emitters of GHGs can be highly exposed to transition risks such as carbon price increases in the near future. Especially, Korean companies have formed an export-oriented and carbon-intensive industrial structure, so GHG reduction regulations aimed at carbon neutrality may lead to increased production and sales costs, lower profits, and declined asset value in the long run. Figure 1 illustrates the trend of portfolio-level carbon intensity for the KOSPI100 index including major domestic large-cap stocks and the S&P500 index set as the comparison group.1) As can be seen in Figure 1, the overall carbon intensity of the Korean stock market–that is, climate risk–is higher than that of developed markets. Hence, it is necessary to manage climate risk from a stock portfolio perspective.

Secondly, if a sufficient number of investors adjust their portfolios to align with carbon-neutral objectives for climate change mitigation, this could function as a long-term incentive for GHG reduction in various industries. There have been stronger efforts to induce the industrial sector to move towards carbon neutrality via the financial sector, with the heavier emphasis on the role and importance of climate finance. Accordingly, a large number of global investors and asset managers have declared their net zero initiative and established related roadmap (Song, 2022). Figure 2 summarizes Korea's climate change response score and ranking among 60 countries in the Climate Change Performance Index2) released by Germanwatch, an international climate assessment institution in Germany. South Korea is found in the bottom ranks, indicating the urgent need for efforts to address the climate crisis. Since the transition to a low-carbon economy is no longer an option but a necessity, Korea needs to strengthen the emissions trading system currently in effect, and provide capital market-based incentives to respond to climate change.

Discussion on how to invest in low-carbon portfolios

Thus far, academia and industry have emphasized awareness of climate risks and the need for risk management (Andersson et al., 2016). More recently, long-term investment approaches aligned with pathways to achieve net-zero have been proposed (Bolton et al., 2022). There are three key considerations when summarizing the discussion and research on the methodology of building a portfolio (or index) that can provide an incentive to reduce GHG emissions while hedging climate risks to some extent.

Firstly, there should be a meaningful reduction in carbon footprint compared to the benchmark. The weighted average carbon intensity is primarily used as a measure of portfolio-level carbon footprint.3) The proxy for carbon risks in a low-carbon portfolio should be significantly lower than that of the benchmark. Secondly, a low-carbon portfolio should track the parent index to some extent and maintain a similar level of risk exposure to that of the parent index. While building a portfolio centered around assets related to renewable energy and eco-friendly services could be considered to mitigate carbon risks in another way, this approach has a very limited scalability in terms of investment scope. Hence, it may not be suitable for large institutional investors' portfolios. Therefore, a method is needed to reduce the carbon footprint of the portfolio while minimizing tracking errors with the parent index. Finally, the risk of greenwashing should be minimized. It is important to consider investments in sectors that need decarbonization with reliable transition plans, rather than solely focusing on companies with lower emissions. This is because investors' continued engagement with companies is essential to providing the companies an incentive for achieving the long-term net-zero goal.

Table 1 sums up various methodologies for building low-carbon portfolios. It is worth evaluating each one of them based on the considerations mentioned above. Firstly, the screening method tries to exclude companies or industries that meet certain criteria. For example, portfolios that do not invest in companies with high fossil fuel revenue shares (e.g., MSCI/S&P Fossil Fuel Free Index) fall under this category. Screening has the advantages of being easy to understand and suitable for performance comparison. However, the drawback is that divestment may make it difficult to engage with companies that require transition and could lead to tracking errors against the parent index. On the other hand, tilting is a method of rebalancing investment based on carbon risk indicators (e.g., the S&P Carbon Efficient index). This is said to be more sustainable than the screening method in that it can provide incentives for decarbonization through continuous investment. However, the downside is that the disparity with the benchmark could widen depending on how to adjust weights. Finally, the algorithm-based optimization method can estimate an optimized portfolio that satisfies the desired level of carbon footprint abatement and disparity reduction if the objective function and constraints are set properly. This is by far the most widely used method in the MSCI Global Low Carbon Target/Leaders Index, and other recently emerging decarbonized indices. Not only does it maintain exposure levels to various risk factors similar to the parent index, but it also minimizes divestment strategies for specific industries, allowing investors to consistently engage with companies. However, its black box-like structure is hard to understand compared to the above two methods, and optimization results can be distorted as the parameters become conservative.

Recently, Europe adopted new rules setting out the minimum technical requirements for climate transition benchmarks that institutional investors can refer to in order to provide guidelines for decarbonized indices, and revised the relevant EU benchmark regulations.4) These 'EU Climate Benchmarks' are classified into EU CTBs and PABs, defined as the requirements for the minimum reduction pathways to achieve the transition to a low-carbon economy based on scientific evidence from the IPCC. What they have in common is that both benchmarks follow a 7% year-on-year decarbonization path, but EU PABs require more stringent standards than EU CTBs.5) Global index providers including MSCI, S&P, and FTSE Russel have recently launched indices.6) They are designed to meet the EU climate benchmark requirements, and to minimize disparities with the parent index through optimization methodology.

Low-carbon portfolio investment and its implications

In overseas cases where ongoing discussions on investor responses to climate change and the methodology of building low-carbon portfolios have persistently taken place, the use of decarbonized indices has increased especially among large asset owners including pension funds. One notable example is AP4, the Swedish national pension fund, which introduced decarbonized indices at first. To hedge carbon risks in their global equity portfolio, AP4 set a new benchmark of the S&P 500 Carbon Efficient Select Index, which tracks the S&P 500 Index to some extent while reducing carbon risks. The index reportedly reduces carbon footprint by 50% compared to the parent index while keeping the disparity ratio under 0.5%. Furthermore, the French Reserve Fund worked together with AP4, MSCI, and Amundi to develop the MSCI Low Carbon Leaders Index series, applying the methodology of constructing low-carbon portfolios to continent-wide passive management. In addition, the New York State Common Retirement Fund, and the California State Teachers' Retirement System have allocated their investment in low-carbon portfolios by setting the FTSE Russell Climate Transition Index and the MSCI ACWI Low Carbon Target Index as a new benchmark, respectively. Moreover, it is observed that the investment landscape for low-carbon portfolios has expanded further as more ETFs tracking decarbonized indices have been consistently listed.

However, investment in low-carbon portfolios has been inactive in Korea. No asset owner in Korea has adopted decarbonized indices as a benchmark similar to overseas cases. Korea's National Pension Service (NPS) has not established concrete coal divestment policies since it declared a coal exit two years ago in May 2021. Although numerous ETFs benchmarking decarbonized indices have been listed since 20217), their net asset value has constantly declined, and net outflows have been observed in all ETFs except for one. This is partly due to a lack of interest from individual investors. But more importantly, the reason behind this is the de facto non-existent demand from institutional investors.

Clear implications can be found in the discussions on low-carbon investment methodologies as part of climate risk responses and the cases of leading index providers and institutional investors. While uncertainties remain, climate risks are likely to materialize in the near future, and South Korea is unlikely to be an exception. If a carbon risk is properly priced and climate risks are appropriately reflected in asset prices, there will be evident impact on investors and portfolios. Long-term investors should consider these climate risks as significant risk factors. Moreover, it is necessary to raise awareness of decarbonization investments and promote related investments in order to facilitate capital market responses to climate change.

1) The reason for limiting the sample to KOSPI100 is that the KOSPI200 sample had many missing values in the carbon emission data provided by Bloomberg.

2) Germanwatch, together with the NewClimate Institute, evaluated the level of climate policy and implementation in 60 countries and the European Union, which account for 90% of global GHG emissions. The result is released as the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) of each country.

3) The weighted average carbon intensity is defined as the exposure-weighted average carbon intensity (=GHG emissions/revenues) of individual companies. This is the most widely used in practice ever since this was approved by the 2017 TCFD recommendations due to its applicability to all asset classes and ease of intuitive understanding (Funk, 2020).

4) In February 2019, the European Parliament and member states agreed to create two types of decarbonization benchmarks: the EU Climate Transition Benchmark (EU CTB) and the EU Paris-Aligned Benchmark (EU PAB). In July 2020, the technical expert group (TEG) of the European Commission adopted new rules that set out minimal technical requirements for the methodology of EU climate benchmarks.

5) For example, the EU PAB demands a minimum of 50% reduction in carbon intensity compared to the parent index and divests from carbon-intensive energy (e.g., coal and oil) companies. On the other hand, the EU CTB has a lower target of 30% without any divestment activities.

6) The MSCI Climate Paris Aligned Indexes, MSCI Climate Change Indexes, S&P Paris-Aligned & Climate Transition index series including the S&P 500 Net Zero 2050 Paris-Aligned ESG Index fall under this category.

7) Notable examples include four KRX/S&P Carbon Efficient Green New Deal ETFs listed on February 5, 2021, and five KRX Climate Change Solution ETFs along with one active ETF listed on October 29, 2021. Both benchmark indices utilized the tilting method in selecting the constituents and computing their weights. Among these, the Carbon Efficient Green New Deal ETF is designed to track the performance of the parent index in the Korean stock market to some extent.

References

Andersson, M., Bolton, P., Samama, F., 2016, Hedging climate risk. Financial Analysts Journal 72(3), 13-32.

Aswani, J., Raghunandan, A., Rajgopal, S., 2023, Are carbon emissions associated with stock returns? Review of Finance, Forthcoming.

Bolton, P., Kacperczyk, M., 2021, Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics 142(2), 517-549.

Bolton, P., Kacperczyk, M., Samama, F., 2022, Net-zero carbon portfolio alignment. Financial Analysts Journal 78(2), 19-33.

Funk C.M., September 2020, Carbon Footprinting: An Investor Toolkit. State Street Global Advisors.

Ibikunle, G., Steffen, T., 2017, European green mutual fund performance: A comparative analysis with their conventional and black peers. Journal of Business Ethics 145, 337-355.

Naqvi, B., Mirza, N., Rizvi, S., Porada-Rochon, M., Itani, R., 2021, Is there a green fund premium? Evidence from twenty-seven emerging markets. Global Finance Journal 50, 100656.

Zhang, S., 2023, Carbon premium: Is it there? Working Paper.

[Korean]

Song, H.S., 2022, Aligning the capital market with the 2050 carbon net zero, KCMI Opinion 2022-02.