Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

National Pension Reform from the Multi-Pillar Pension Perspective

Publication date Nov. 19, 2019

Summary

Korea’s state-run National Pension scheme has a partially-funded, pay-as-you-go element where the current generation benefits from contributions by the past generation. Under such an intergenerational structure, it’s desirable for policy objectives to prioritize intergenerational, contribution-benefit equity ahead of other factors such as concerns about old-age income security. The partially-funded structure could be understood as a buffer that helps smooth out the contribution burden and benefits across generations. As the multi-pillar pension scheme is beginning to take hold in Korea, it’s reasonable to take a multi-pillar perspective in judging the adequacy of post-retirement income security (the income replacement ratio), one of the National Pension’s fundamental objectives. In this regard, the reform on the National Pension scheme should prioritize the fund’s role as a buffer for financial sustainability. In addition to the gradual increase in premiums, it’s worth benchmarking the US Social Security 2100 Act to come up with other measures that could help delay the fund’ s depletion, e.g., raising the ceiling on pensionable earnings, transferring the income tax on state pension benefits back to the fund, etc.

Regulatory puzzle for National Pension reform

Under a normal demographic structure where the younger generation outnumbers the older one and thereby pension contributions surpass payouts, it’s possible to come up with a proper policy mix that perfectly does away with structural conflicts between a pension’sfinancial sustainability, contributions, and old-age income security. As the economy is plagued by rapid population ageing and the lingering downward spiral of the birth rate, the three policy objectives pose the National Pension a baffling puzzle whose solution requires a serious compromise of at least one objective. With keeping the current contribution levels intact, it’s impossible to satisfy financial sustainability and old-age income security at all. Stronger income security without a sizable increase in contributions would be possible only at the expense of the pension’s long-term sustainability. And any move to strengthen the sustainability would come at the expense of old-age income security. Against the backdrop of such a trilemma, which objective should the National Pension pursue or abandon? The solution to the complex puzzle lies in the answer to this question.

According to the National Pension’s financial calculation scheme, Korea’s government devised a reform bill on Korea’s National Pension in October 2018, which went through the Economic, Social & Labor Council (ESLC, hereinafter) to be submitted to the National Assembly. After the initial government proposal had been adjusted to four plans for higher old-age income security (the income replacement ratio), it was again scaled down to three plans during the ESLC deliberation process. One of the three plans is to maintain the status quo. The second one is to raise the premium by three percentage points to increase the income replacement ratio from today’s 40% to 45%, which could delay the pension’s depletion for seven years. This is supported by the ESLC majority. The last one is to raise the premium by one percentage point to keep the current income replacement ratio and delay the depletion for three years. The initial government proposal included a rise in contribution to increase the basic pension, or to make the income replacement ratio as high as 50%. In short, the overall policy direction or intention behind the reform is to raise contributions for higher old-age income security (the income replacement ratio), dealing with the aforementioned trilemma with stronger income security at the expense of the pension’s financial sustainability. Such a direction for a mid-term reform is somewhat contradicting with the regulatory path the National Pension had taken in the past.

Past reforms focusing on intergenerational equity

Korea’s state-run pension is a partially-funded, pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme, including an intergeneration structure where the current generation receives the contributions accumulated by earlier generations. Unlike in private plan where contributions are accumulated in each individual account, partially-funded contributions in such an intergenerational model play only one role as a buffer smoothing out contribution burden and pension benefits across generations. More specifically, the buffer guarantees the scheme’s equity as well as sustainability by making adjustments to prevent one generation from getting too much burden or benefits. The size of the buffer depends on the pension’s balance sheet as well as the demographic structure. For reference, Korea’ National Pension has accumulated a sizable buffer (26 times the reserve ratio) against Korea’s rapid population ageing and low birth rate. Unlike private plans, public plans such as the National Pension preconditions the purpose of being, and the stability of the scheme. While the former means adequate old-age income security (income replacement ratios), the latter refers to equity across generations. If contribution or benefit (replacement ratios) levels disadvantage future generations, this could exacerbate the scheme’s long-term sustainability. If the National Pension is projected to be depleted by about 2060 and then switched to a PAYG scheme, this is expected to raise future generations’ burden (PAYG cost ratio) two- to three-fold to 24% to 29% from today’s 9% under the fourth financial calculation assuming the income replacement ratio of 40%. This will seriously undermine intergenerational, contribution-benefit equity. Under such a projection, it’s unrealistic to expect the current scheme to shift towards a PAYG scheme smoothly.

A reflection on past National Pension reforms also confirms the focus of policy directions on intergenerational equity. Since the National Pension came to cover every citizen in 1998, Korea has introduced a financial calculation scheme based on a 5-year cycle, and pursued contribution and benefit policies focusing on financial sustainability. When concerns about depletion were raised amid the Asian financial crisis, rapid population ageing and falling birth rates, a series of downward adjustments were made to the income replacement ratio from 70% to 60%, and again to 40% in 2007. The policy focus has been on to delay the pension’s depletion. Due to the fast-paced population ageing in Korea, the timing of depletion was delayed for only 13 years from 2047 to 2060. However, what’s important is that the long-term, fundamental policy stance has centered on a balance in intergenerational equity in preparation for fund depletion.

Income replacement ratio from the multi-pillar perspective

It’s worth looking at if the proposed reform for stronger income security could be understood as a return to the past, aiming to offset a series of “excessive” decreases in income replacement ratios. Admittedly, the National Pension’s benefits have dwindled continuously since its inception in 1988. At the beginning, the income replacement ratio was 70%, taking into account the international standard that post-retirement income should be around 70% of pre-retirement income. At that time, Korea has a single-pillar pension scheme where the National Pension is the only post-retirement plan. However, as Korea went through the Asian financial crisis and learned a lot from pension reforms in developed countries as well as recommendations from international organizations such as the OECD and ILO, it gradually switched its pension scheme into a multi-pillar one by introducing qualified personal pensions in 2004, and the occupational retirement pension in 2005. The rationale behind this could be that the adequacy of the income replacement ratio for old-age income security should be judged from a multi-pillar perspective, instead of considering only one, specific pension scheme. The 2008 long-term plan that confidently proposed to significantly decrease the National Pension’s income replacement ratio must have been based on the rationale that a policy stance prioritizing financial sustainability would not undermine old-age income security under a multi-pillar pension environment. Furthermore, Korea’s defined benefit plans have a structure that is unaffected by population ageing. Under the circumstances, the public pension can focus its policy objective on intergenerational equity via financial sustainability.

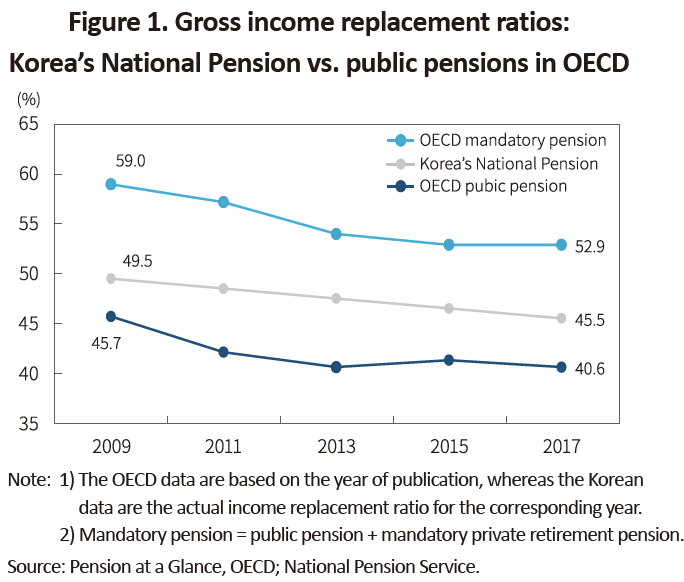

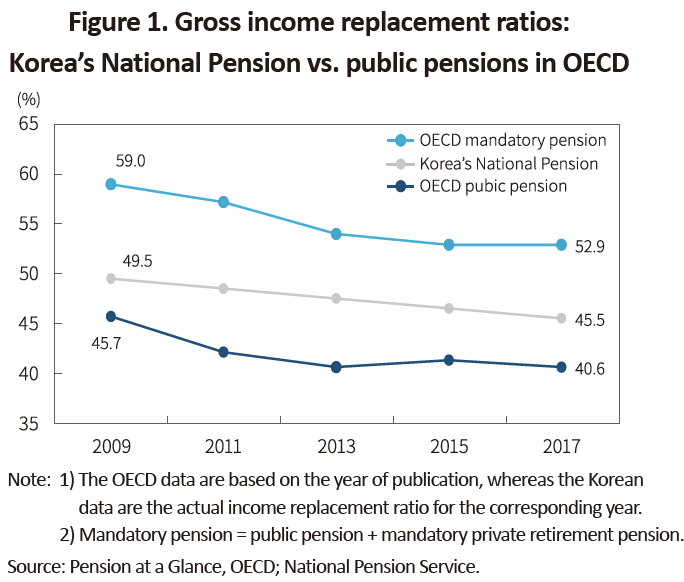

Also worth noting is that the National Pension’s income replacement ratio is not low under the international standard. The ratio will gradually decline by 0.5 percentage points every year from the current 50% to strike 40% by 2028. As of 2017, the income replacement ratio was 45.5%, higher than the OECD average of 40.6%. The 2028 income replacement ratio of 40% is close to the OECD average for public pensions.1) As Figure 1 illustrates, the OECD income replacement ratio for public pensions has fallen steadily. The National Pension’s income replacement ratio is expected to dwarf the OECD average for a substantial period of time. The focus of the proposed reform, based on the fourth financial calculation, on a higher income replacement ratio isn’t very convincing. As shown in Figure 1, what’s important in old-age income security is the income replacement ratio for mandatory schemes. In Korea, the National Pension is the only mandatory pension, making the income replacement ratio of the mandatory pension equal to the ratio of the National Pension. However, many developed countries have undergone pension reforms to mandate the private, retirement pension. In terms of the mandatory pension, the OECD average income replacement ratio stood at 52.9% in 2017, far higher than the ratio of Korea’s National Pension. This gives us one clear implication. The level of old-age income security should be judged based on a multi-pillar perspective. Toward that end, it is advisable that the government broaden the mandatory pension scheme from the National Pension to the private scheme. This adds both legitimacy and urgency to the mandated retirement pension scheme for which the government is pushing.

1) As of 2017, the income replacement ratio estimated by the NPS (45.5%) is far from the OECD estimate (39.3%) that assumes an average subscriber entering the labor market at age 20 in 2016 to work for 40 years. On the contrary, the NPS estimate is the income replacement ratio actually applied in 2017. In terms of the OECD estimate, Korea’s public pension income replacement ratio is close to the OECD average.

Under a normal demographic structure where the younger generation outnumbers the older one and thereby pension contributions surpass payouts, it’s possible to come up with a proper policy mix that perfectly does away with structural conflicts between a pension’sfinancial sustainability, contributions, and old-age income security. As the economy is plagued by rapid population ageing and the lingering downward spiral of the birth rate, the three policy objectives pose the National Pension a baffling puzzle whose solution requires a serious compromise of at least one objective. With keeping the current contribution levels intact, it’s impossible to satisfy financial sustainability and old-age income security at all. Stronger income security without a sizable increase in contributions would be possible only at the expense of the pension’s long-term sustainability. And any move to strengthen the sustainability would come at the expense of old-age income security. Against the backdrop of such a trilemma, which objective should the National Pension pursue or abandon? The solution to the complex puzzle lies in the answer to this question.

According to the National Pension’s financial calculation scheme, Korea’s government devised a reform bill on Korea’s National Pension in October 2018, which went through the Economic, Social & Labor Council (ESLC, hereinafter) to be submitted to the National Assembly. After the initial government proposal had been adjusted to four plans for higher old-age income security (the income replacement ratio), it was again scaled down to three plans during the ESLC deliberation process. One of the three plans is to maintain the status quo. The second one is to raise the premium by three percentage points to increase the income replacement ratio from today’s 40% to 45%, which could delay the pension’s depletion for seven years. This is supported by the ESLC majority. The last one is to raise the premium by one percentage point to keep the current income replacement ratio and delay the depletion for three years. The initial government proposal included a rise in contribution to increase the basic pension, or to make the income replacement ratio as high as 50%. In short, the overall policy direction or intention behind the reform is to raise contributions for higher old-age income security (the income replacement ratio), dealing with the aforementioned trilemma with stronger income security at the expense of the pension’s financial sustainability. Such a direction for a mid-term reform is somewhat contradicting with the regulatory path the National Pension had taken in the past.

Past reforms focusing on intergenerational equity

Korea’s state-run pension is a partially-funded, pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme, including an intergeneration structure where the current generation receives the contributions accumulated by earlier generations. Unlike in private plan where contributions are accumulated in each individual account, partially-funded contributions in such an intergenerational model play only one role as a buffer smoothing out contribution burden and pension benefits across generations. More specifically, the buffer guarantees the scheme’s equity as well as sustainability by making adjustments to prevent one generation from getting too much burden or benefits. The size of the buffer depends on the pension’s balance sheet as well as the demographic structure. For reference, Korea’ National Pension has accumulated a sizable buffer (26 times the reserve ratio) against Korea’s rapid population ageing and low birth rate. Unlike private plans, public plans such as the National Pension preconditions the purpose of being, and the stability of the scheme. While the former means adequate old-age income security (income replacement ratios), the latter refers to equity across generations. If contribution or benefit (replacement ratios) levels disadvantage future generations, this could exacerbate the scheme’s long-term sustainability. If the National Pension is projected to be depleted by about 2060 and then switched to a PAYG scheme, this is expected to raise future generations’ burden (PAYG cost ratio) two- to three-fold to 24% to 29% from today’s 9% under the fourth financial calculation assuming the income replacement ratio of 40%. This will seriously undermine intergenerational, contribution-benefit equity. Under such a projection, it’s unrealistic to expect the current scheme to shift towards a PAYG scheme smoothly.

A reflection on past National Pension reforms also confirms the focus of policy directions on intergenerational equity. Since the National Pension came to cover every citizen in 1998, Korea has introduced a financial calculation scheme based on a 5-year cycle, and pursued contribution and benefit policies focusing on financial sustainability. When concerns about depletion were raised amid the Asian financial crisis, rapid population ageing and falling birth rates, a series of downward adjustments were made to the income replacement ratio from 70% to 60%, and again to 40% in 2007. The policy focus has been on to delay the pension’s depletion. Due to the fast-paced population ageing in Korea, the timing of depletion was delayed for only 13 years from 2047 to 2060. However, what’s important is that the long-term, fundamental policy stance has centered on a balance in intergenerational equity in preparation for fund depletion.

Income replacement ratio from the multi-pillar perspective

It’s worth looking at if the proposed reform for stronger income security could be understood as a return to the past, aiming to offset a series of “excessive” decreases in income replacement ratios. Admittedly, the National Pension’s benefits have dwindled continuously since its inception in 1988. At the beginning, the income replacement ratio was 70%, taking into account the international standard that post-retirement income should be around 70% of pre-retirement income. At that time, Korea has a single-pillar pension scheme where the National Pension is the only post-retirement plan. However, as Korea went through the Asian financial crisis and learned a lot from pension reforms in developed countries as well as recommendations from international organizations such as the OECD and ILO, it gradually switched its pension scheme into a multi-pillar one by introducing qualified personal pensions in 2004, and the occupational retirement pension in 2005. The rationale behind this could be that the adequacy of the income replacement ratio for old-age income security should be judged from a multi-pillar perspective, instead of considering only one, specific pension scheme. The 2008 long-term plan that confidently proposed to significantly decrease the National Pension’s income replacement ratio must have been based on the rationale that a policy stance prioritizing financial sustainability would not undermine old-age income security under a multi-pillar pension environment. Furthermore, Korea’s defined benefit plans have a structure that is unaffected by population ageing. Under the circumstances, the public pension can focus its policy objective on intergenerational equity via financial sustainability.

Also worth noting is that the National Pension’s income replacement ratio is not low under the international standard. The ratio will gradually decline by 0.5 percentage points every year from the current 50% to strike 40% by 2028. As of 2017, the income replacement ratio was 45.5%, higher than the OECD average of 40.6%. The 2028 income replacement ratio of 40% is close to the OECD average for public pensions.1) As Figure 1 illustrates, the OECD income replacement ratio for public pensions has fallen steadily. The National Pension’s income replacement ratio is expected to dwarf the OECD average for a substantial period of time. The focus of the proposed reform, based on the fourth financial calculation, on a higher income replacement ratio isn’t very convincing. As shown in Figure 1, what’s important in old-age income security is the income replacement ratio for mandatory schemes. In Korea, the National Pension is the only mandatory pension, making the income replacement ratio of the mandatory pension equal to the ratio of the National Pension. However, many developed countries have undergone pension reforms to mandate the private, retirement pension. In terms of the mandatory pension, the OECD average income replacement ratio stood at 52.9% in 2017, far higher than the ratio of Korea’s National Pension. This gives us one clear implication. The level of old-age income security should be judged based on a multi-pillar perspective. Toward that end, it is advisable that the government broaden the mandatory pension scheme from the National Pension to the private scheme. This adds both legitimacy and urgency to the mandated retirement pension scheme for which the government is pushing.

A higher ceiling on pensionable income

The proposed government plan links higher premiums to a higher income replacement ratio, meaning that a hike in premiums is for higher old-age income security. Such a policy putting income security ahead of intergenerational equity has low dynamic compatibility from the perspective of the past long-term policy stance. As mentioned above, the National Pension’s income replacement ratio is not low compared to that of developed countries. If income security is still at issue, it’s advisable to come up with how to raise old-age income security without any increase in premiums. One of them could be to raise the ceiling of pensionable earnings, which was also discussed by the ESLC. As of 2018, the ceiling is KRW 4.68 million per month. This equals to about two-fold the average monthly income of all subscribers. Adjusting the ceiling would raise the average monthly income, and guarantee a higher income replacement ratio for low-income earners. Among developed economies, the US ceiling is placed at 262% of the average income. A Social Security expansion bill proposes to substantially raise the ceiling from the current $130,000 to $400,000. However, a rise in pensionable earnings will not only affect the income replacement ratio, but also other areas such as redistribution, pension depletion, etc. A higher ceiling on pensionable earnings has an effect of pushing up the A value (the average earnings of the insured), thereby increasing the average income replacement ratio as well as the ratio for low-income earners. But this will at the same time affect the timing of pension depletion because the National Pension’s income replacement constant is higher than 1 (1.2) after the year of 2028 when the income replacement ratio turns 40%. This means that high-income earners will receive higher benefits, which will adversely affect the timing of pension depletion. Hence, a simulation using the National Pension’s financial data is required to find an optimal level that could effectively minimizes adverse effects such as pension depletion.

Income tax on pension benefits transferred back to the fund

A problem in the higher ceiling is the adverse effect of high-income earners’ high benefits on pension depletion. To deal with the issue, it’d be effective to model after the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program in the US. As part of the 1983 reform, the US introduced a scheme where the income tax charged to high-income earners’ benefits would be transferred back to the OASDI program. This is purposed to improve financing as well as interclass equity by imposing a progressive income tax on high benefits, which is to be transferred back to the program. Now, this accounts for about 4% of the program’s total annual income. Currently, Korea has only 4.8 million pensioners who receive benefits from the National Pension, among which only 5% receive more than KRW 1 million and thus are subject to the income tax. Hence, the income tax from the National Pension is not estimated to be large. However, if the number of pensioners increases to 17 million or 18 million, the proportion of subscribers earning higher than the pensionable income ceiling (KRW 4.68 million in 2018) is estimated to reach 13%. Under the circumstances, the revenue from the income tax on pension benefits is expected to rise. It’s desirable to think about transferring the revenue back to the National Pension Fund. Especially, such a scheme could effectively deal with the potential conflicts that are expected to arise when the raised ceiling on pensionable income could widen the differences in pension benefits low- and high-wage earners will receive. At the same time, the transfer of the income tax on high pension benefits back to the NPF will help ease the fund’s financial problem. Although the government’s role in ensuring the benefits from the National Pension is also critical from a wider perspective, this could help the NPF not only justify their long-term financing, but also enjoy practical benefits. As part of Korea’s four schemes of social insurance, the government provides the NPF about KRW 600 billion (0.09% of NPF income) for replenishing benefits to low-wage earners. Aside from this, it’s possible to push for the use of the income tax on pension benefits for NPF financing as suggested here.

Long-term financial plans for intergenerational equity

Under the projection of the PAYG cost ratio reaching 23%, it’s recommended to devise a long-term measure for the pension’s sustainability with a sense of urgency. For future policy directions, it’s worth reviewing discussions recently having taken place in the US. In the US Congress, legislative hearings on the Social Security 2100 Act have been underway. According to the US Social Security Administration, the OASDI funds are to be depleted in 15 years in 2034, much earlier than the National Pension. The Social Security 2100 Act is proposed to stabilize the financial conditions of the funds. The figure, 2100, symbolizes a long-term nature of the plan and the year until which the depletion could be delayed (2093 is a more accurate figure, though). Although the proposed bill contains many other provisions, the core element is to raise the premium by 0.1 percentage points per year for the next two decades until 2043, which will raise today’s 12.4% to 14.8%. The rationale behind this bill is that the projected depletion in 2034 will decrease pension benefits to 80% of today’s level. With a gradual increase in premiums, the US tries to delay the depletion for 60 to 70 years as well as to purse financial stability and intergenerational equity. Although the bill includes a provision for a phased increase in benefits based on a new formula, its policy objective is not the targeted income replacement ratio as is in Korea. For reference, the income replacement ratio of the OASDI funds is set at 38.3% according to the OECD standard.

Any increase in premiums, if there is one, should be used for delaying the depletion, instead of a higher income replacement ratio. With the projection clearly indicating the National Pension running out in 2057, a three- to seven-year delay the current reform proposes is not impressive enough. A desirable plan should suggest a long-term measure that pursues financial sustainability as seen in the case of the US Social Security 2100 Act. The National Pension’s long-term financial projection and the change in Korea’s demographic structure underlying the projection should provide a hint about what constitutes a proper long-term plan.

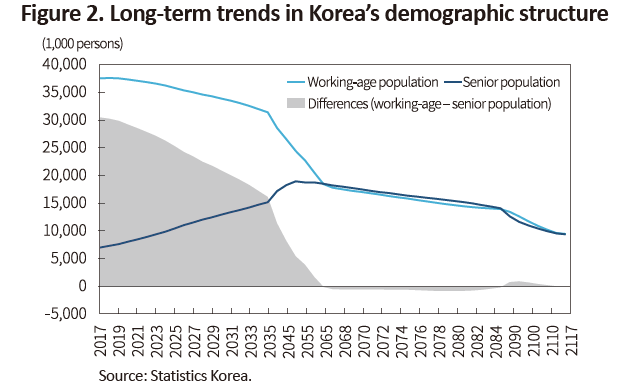

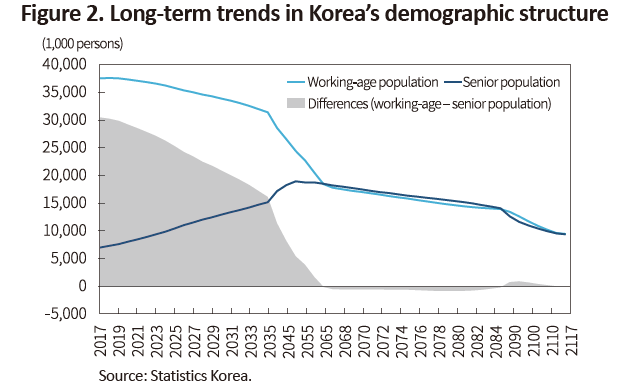

Figure 2 below shows Population Projections for Korea for 2117 by Statistics Korea. It’s possible to pinpoint the timing at which the National Pension balance will change, based on the assumption that National Pension subscribers making contributions are the working-age population, and that prospective pensioners are the senior population. According to the projections, Korea will see its population ageing rapidly until the number of senior population becomes equal to the working-age population around 2065. For over the next two decades from there, the senior population will outnumber the working-age population by about 750,000 persons. Even after 2085, the size of the senior population will stay the same for three more decades. The implication of this data for the National Pension is clear. The balance of the pension will deteriorate at the retirement of baby boomers, but it won’t get any better even after the baby boomers disappear from the demographic data (more precisely, 2043 for the first generation baby boomers and 2055 for the second generation baby boomers based on their life expectancy). On top of the shock from baby boomers, Korea has another demographic shock waiting to hit the economy: the rapidly falling birth rate that will drastically shrink the future working-age population. Under such a demographic structure for the looming century, a desirable reform on the National Pension scheme will have to focus on intergenerational equity, requiring the current generation with more working-age subscribers to pay more premiums for a few more decades with the aim to reduce the excessive burden (the 20% PAYG cost ratio) that would otherwise be passed on to future generations. Among others, Korea needs to benchmark the US case to set up a long-term plan, for example, tentatively dubbed as “the Pension Reform 2080” or so, that helps delay pension depletion at least until 2080 when Korea’s working-age population is expected to outnumber the senior population again. Inevitably, such a long-term plan involves a schedule for premium hikes. But we can’t afford to wait longer before setting up and implementing the plan for spreading out the burden evenly across all generations because the demographic data clearly tell us that the working-age population outnumbers the senior population by 15 million to 30 million only until the 2040s.

The proposed government plan links higher premiums to a higher income replacement ratio, meaning that a hike in premiums is for higher old-age income security. Such a policy putting income security ahead of intergenerational equity has low dynamic compatibility from the perspective of the past long-term policy stance. As mentioned above, the National Pension’s income replacement ratio is not low compared to that of developed countries. If income security is still at issue, it’s advisable to come up with how to raise old-age income security without any increase in premiums. One of them could be to raise the ceiling of pensionable earnings, which was also discussed by the ESLC. As of 2018, the ceiling is KRW 4.68 million per month. This equals to about two-fold the average monthly income of all subscribers. Adjusting the ceiling would raise the average monthly income, and guarantee a higher income replacement ratio for low-income earners. Among developed economies, the US ceiling is placed at 262% of the average income. A Social Security expansion bill proposes to substantially raise the ceiling from the current $130,000 to $400,000. However, a rise in pensionable earnings will not only affect the income replacement ratio, but also other areas such as redistribution, pension depletion, etc. A higher ceiling on pensionable earnings has an effect of pushing up the A value (the average earnings of the insured), thereby increasing the average income replacement ratio as well as the ratio for low-income earners. But this will at the same time affect the timing of pension depletion because the National Pension’s income replacement constant is higher than 1 (1.2) after the year of 2028 when the income replacement ratio turns 40%. This means that high-income earners will receive higher benefits, which will adversely affect the timing of pension depletion. Hence, a simulation using the National Pension’s financial data is required to find an optimal level that could effectively minimizes adverse effects such as pension depletion.

Income tax on pension benefits transferred back to the fund

A problem in the higher ceiling is the adverse effect of high-income earners’ high benefits on pension depletion. To deal with the issue, it’d be effective to model after the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program in the US. As part of the 1983 reform, the US introduced a scheme where the income tax charged to high-income earners’ benefits would be transferred back to the OASDI program. This is purposed to improve financing as well as interclass equity by imposing a progressive income tax on high benefits, which is to be transferred back to the program. Now, this accounts for about 4% of the program’s total annual income. Currently, Korea has only 4.8 million pensioners who receive benefits from the National Pension, among which only 5% receive more than KRW 1 million and thus are subject to the income tax. Hence, the income tax from the National Pension is not estimated to be large. However, if the number of pensioners increases to 17 million or 18 million, the proportion of subscribers earning higher than the pensionable income ceiling (KRW 4.68 million in 2018) is estimated to reach 13%. Under the circumstances, the revenue from the income tax on pension benefits is expected to rise. It’s desirable to think about transferring the revenue back to the National Pension Fund. Especially, such a scheme could effectively deal with the potential conflicts that are expected to arise when the raised ceiling on pensionable income could widen the differences in pension benefits low- and high-wage earners will receive. At the same time, the transfer of the income tax on high pension benefits back to the NPF will help ease the fund’s financial problem. Although the government’s role in ensuring the benefits from the National Pension is also critical from a wider perspective, this could help the NPF not only justify their long-term financing, but also enjoy practical benefits. As part of Korea’s four schemes of social insurance, the government provides the NPF about KRW 600 billion (0.09% of NPF income) for replenishing benefits to low-wage earners. Aside from this, it’s possible to push for the use of the income tax on pension benefits for NPF financing as suggested here.

Long-term financial plans for intergenerational equity

Under the projection of the PAYG cost ratio reaching 23%, it’s recommended to devise a long-term measure for the pension’s sustainability with a sense of urgency. For future policy directions, it’s worth reviewing discussions recently having taken place in the US. In the US Congress, legislative hearings on the Social Security 2100 Act have been underway. According to the US Social Security Administration, the OASDI funds are to be depleted in 15 years in 2034, much earlier than the National Pension. The Social Security 2100 Act is proposed to stabilize the financial conditions of the funds. The figure, 2100, symbolizes a long-term nature of the plan and the year until which the depletion could be delayed (2093 is a more accurate figure, though). Although the proposed bill contains many other provisions, the core element is to raise the premium by 0.1 percentage points per year for the next two decades until 2043, which will raise today’s 12.4% to 14.8%. The rationale behind this bill is that the projected depletion in 2034 will decrease pension benefits to 80% of today’s level. With a gradual increase in premiums, the US tries to delay the depletion for 60 to 70 years as well as to purse financial stability and intergenerational equity. Although the bill includes a provision for a phased increase in benefits based on a new formula, its policy objective is not the targeted income replacement ratio as is in Korea. For reference, the income replacement ratio of the OASDI funds is set at 38.3% according to the OECD standard.

Any increase in premiums, if there is one, should be used for delaying the depletion, instead of a higher income replacement ratio. With the projection clearly indicating the National Pension running out in 2057, a three- to seven-year delay the current reform proposes is not impressive enough. A desirable plan should suggest a long-term measure that pursues financial sustainability as seen in the case of the US Social Security 2100 Act. The National Pension’s long-term financial projection and the change in Korea’s demographic structure underlying the projection should provide a hint about what constitutes a proper long-term plan.

Figure 2 below shows Population Projections for Korea for 2117 by Statistics Korea. It’s possible to pinpoint the timing at which the National Pension balance will change, based on the assumption that National Pension subscribers making contributions are the working-age population, and that prospective pensioners are the senior population. According to the projections, Korea will see its population ageing rapidly until the number of senior population becomes equal to the working-age population around 2065. For over the next two decades from there, the senior population will outnumber the working-age population by about 750,000 persons. Even after 2085, the size of the senior population will stay the same for three more decades. The implication of this data for the National Pension is clear. The balance of the pension will deteriorate at the retirement of baby boomers, but it won’t get any better even after the baby boomers disappear from the demographic data (more precisely, 2043 for the first generation baby boomers and 2055 for the second generation baby boomers based on their life expectancy). On top of the shock from baby boomers, Korea has another demographic shock waiting to hit the economy: the rapidly falling birth rate that will drastically shrink the future working-age population. Under such a demographic structure for the looming century, a desirable reform on the National Pension scheme will have to focus on intergenerational equity, requiring the current generation with more working-age subscribers to pay more premiums for a few more decades with the aim to reduce the excessive burden (the 20% PAYG cost ratio) that would otherwise be passed on to future generations. Among others, Korea needs to benchmark the US case to set up a long-term plan, for example, tentatively dubbed as “the Pension Reform 2080” or so, that helps delay pension depletion at least until 2080 when Korea’s working-age population is expected to outnumber the senior population again. Inevitably, such a long-term plan involves a schedule for premium hikes. But we can’t afford to wait longer before setting up and implementing the plan for spreading out the burden evenly across all generations because the demographic data clearly tell us that the working-age population outnumbers the senior population by 15 million to 30 million only until the 2040s.

1) As of 2017, the income replacement ratio estimated by the NPS (45.5%) is far from the OECD estimate (39.3%) that assumes an average subscriber entering the labor market at age 20 in 2016 to work for 40 years. On the contrary, the NPS estimate is the income replacement ratio actually applied in 2017. In terms of the OECD estimate, Korea’s public pension income replacement ratio is close to the OECD average.