Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Monetary Policy in the Super-low Rate Era

Publication date Jan. 21, 2020

Summary

Amid Korea’s structural growth slowdown and the Bank of Korea’s cut in the base rate to the unprecedented low level of 1.25%, more attention is paid on Korea’s future moves in the super-low interest rate era. Given the effective lower bound risk where a country cannot cut the interest rate further despite an economic slump due to its less effective monetary policy, further research is needed to estimate Korea’s effective lower bound level, and to develop new policy tools to mobilize if the economy reaches the effective lower bound, which should reflect on developed countries’ experience of super-low interest rates.

Since the Monetary Policy Board of the Bank of Korea (BOK) cut its base rate to 1.25% in October 2019, financial circles, mainly research institutes, have been engaged in active discussions on the possibility of the super-low, zero interest rate era, and future responses. Many research institutes forecast that Korea’s economic growth for 2020 would be well below the lower 2% range, lower than the potential growth with inflation far below the 2% BOK target. With the lower-for-longer growth and interest rates in the post-crisis era, the potential growth is expected to hover around the mid 1% range in the mid-2020s amid population ageing and the absence of growth drivers. Under the circumstances, the issue of super-low interest rates could pose a mid- to long-term, if not imminent one for 2020, challenge to financial institutions making profits out of intermediation, and the BOK that implements monetary policy.

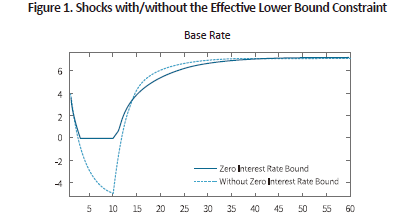

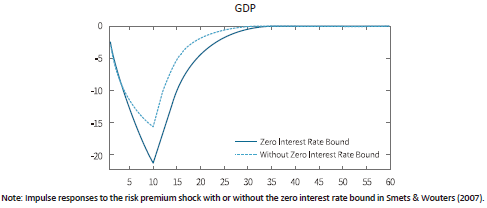

Although monetary policy as well as fiscal policy have long served a stabilizing function in the macroeconomy, there’re questions about future policy effects as major central banks keep their base rates at the lowest levels, aiming to weather the financial crisis and the resultant fall in potential growth in the global economy. Central banks tend to cut interest rates in response to the recession, but they can’t cut the rate indefinitely. Interest rates below a certain level could lead to an abrupt decline in monetary policy effectiveness, capital outflows or other adverse effects. That level is called an effective lower bound. If the base rate is already close to the effective lower bound so that an economy can’t cut the rate further during a recession, this could further worsen the real economic recession. Figure 1 demonstrates the risk inherent in the effective lower bound. If the base rate is close to the 0% effective lower bound, a negative impact on the economy will bring down GDP more drastically, compared to when it’s possible to cut the interest rate without the effective lower bound constraint. Also notable is the risk of the effective lower bound arises even when a rate cut is constrained by the effective lower bound. Recent research findings show that the inflation expectations fall and current inflation stagnates with the recent rise in the possibility of tail risk where declining real interest rates lead to the effective lower bound constraint (Hills, et al., 2019; Amano, et al., 2019; Mertens & Williams, 2019; Kiley & Roberts, 2017).

Important questions related to the effective lower bound are what the level of Korea’s effective lower bound is, and how Korea should react to the effective lower bound. Although the BOK in charge of Korea’s monetary policy has yet to officially mention the level of Korea’s effective lower bound, BOK Governor Juyeol Lee repeatedly stated that the effective lower bound is higher than that of key currency nations given Korea’s capital outflow risk, etc.1) In the same vein, securities firm analysts in a survey forecast that the effective lower bound of Korea’s base rate would be between 0.75% and 1.00%.2) However, capital outflows seem unlikely for the time being given that foreign capital seeking for arbitrage trading is flowing into Korea’s debt market despite the long-term inversion between Korean and US policy rates.

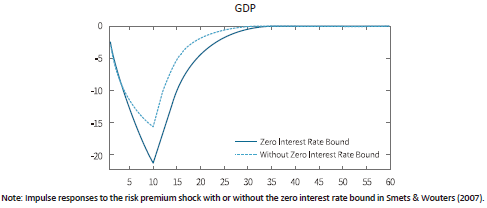

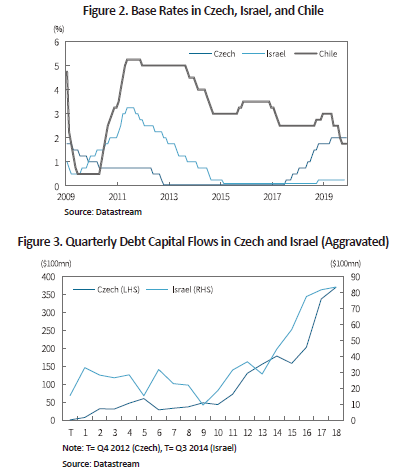

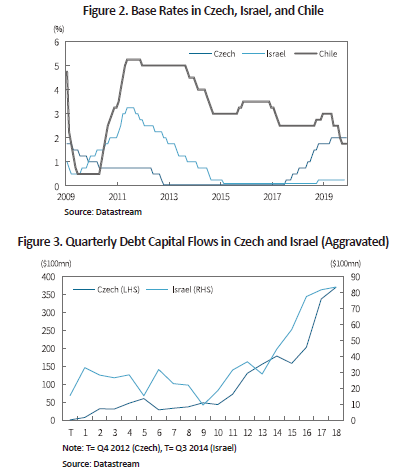

As widely known, some developed economies such as Sweden and Denmark on top of key-currency nations shifted to negative interest rate policies. Among emerging economies, Czech, Chile, and Israel adopted super-low interest rates in the face of severe economic slumps and low inflation. Czech entered the zero interest rate (0.05%) in November 2012, and its economic growth recorded –0.8% and –0.5%, in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In addition, Israel cut the base rate to 0.25% in September 2014, and again to 0.1% in March 2015, which resulted in inflation of –0.6% and –0.5% in 2015 and 2016, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 3, Czech and Israel that kept zero interest rates for years did see capital flowing into the debt markets. Especially, the Czech koruna was under appreciation pressure against the euro amid the European Central Bank’s monetary easing. The super-low interest rate policies in those two nations, on top of the global economic recovery, could be presumably attributable to the economic recovery because after four to five years of super-low rates both countries succeeded to rebound from the recession and low inflation, finally managing to raise their rates.3) Further in-depth research is required to assess the level of the effective lower bound taking into account the impact on financial stability4) and policy paths, etc. But concluding cautiously, the interest rate might be lowered further than market participants now expect if economic conditions deteriorate seriously.

How to respond to the risk of the effective lower bound has received relatively high academic attention in the post-crisis era. Central banks in developed countries are known to carry out large-scale asset purchases, provide forward guidance, or provide low-rate liquidity for inducing private sector financial institutions to increase lending. Such policy tools are proven effective in many subsequent studies. One of the recent studies, Eberly, et al. (2019) assesses that unconventional monetary policy tools adopted by the Fed led to a real economic boost measured as a 100bp cut in the Fed funds rate, which contributed to the early recovery of the US economy from the financial crisis. In Europe, ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane argues that ECB’s unconventional tools in the post crisis era were highly effective for facilitating economic growth and inflation (Lane, 2019).

As in developed economies, the BOK has an established framework that could enable unconventional monetary tools if necessary. Already, the BOK uses the Bank Intermediated Lending Support Facility, via which to supply funds at low rates (0.5% to 0.75%) aiming to support new growth and employment, stabilize loans to SMEs, etc. Also it has established tools such as Monetary Policy Reports, Monetary Policy Decisions, and press conferences to better communicate monetary policy with the market. Article 68 of the Bank of Korea Act defines government bonds and the securities designated by the Monetary Policy Board as eligible assets for open market operations. That does away with any legal constraint on the type of eligible securities for the BOK’s quantitative easing program.5) However, further research is needed in the size and eligible securities of quantitative easing, given Korea’s long-term fiscal prudence and the small size of government debt issuance relative to its GDP, as well as the solid demand for government debt among pension funds and insurers.6) It’s worth noting that Czech responded to the zero interest rate with, instead of quantitative easing, policy measures that set up the lower bound exchange rate (27 koruna per euro) and maintained that level via market intervention. It tried to prevent currency from appreciating in seeking to maintain export competiveness, and responded to downward pressure on inflation resulted from declining import prices. Meanwhile, the intervention to purchase the dollar and the euro pushed up the koruna liquidity. More recently, the IMF views positively such policy impacts on the real economy (Caseli, 2017).

It’s true that Korea lacks research and analyses on how to apply unconventional monetary policy tools adopted by the Fed or the ECB to the Korean economy because Korea’s economic condition hasn’t been as bad as requiring those tools thus far. However, in the Monetary Policy for 2020 report, the BOK said it was set to bolster analyses on monetary policy tools other than the interest rate in response to changes in economic conditions. Taking into account a looming structural slowdown in the Korean economy, it is hoped that further studies shed light on a diversified areas such as the changes in the financial markets and the economic system, new monetary policy tools fit for Korea’s economy, and an optimal policy mix with fiscal policy.

1) “It’s uncertain where the effective lower bound is exactly, but it should exist somewhere. And what I can tell you is there’s a shared consensus among Monetary Policy Board members that the effective lower bound is located at a slightly higher level in non-key-currency nations, compared to that in key-currency nations.” (Press conference for monetary policy, Oct. 16, 2019)

2) News1 (Oct. 13, 2019), [Monetary Policy Poll] 2) 50% of analysts surveyed agreed on “Korea’s effective lower bound on the base rate at 0.75%”.

3) As illustrated in Figure 2, fund flows to debt began rising steeply when the economy showed a clear sign of recovery and a rate hike. Forbes (2018) calls the zero-interest rate policy ‘sticky’ in that a rate hike could be delayed because a hinted rate hike after zero-rate policy immediately leads to currency appreciation and import price falls, forming downward pressure on inflation.

4) Czech and Israel had stable household debt to GDP ratios of 30% to 40% during the zero-rate period, whereas the ratios rose in Sweden and other nations whose ratios had been already high before zero-rate policy.

5) At the height of the global financial crisis (Oct. 27, 2018), the BOK temporarily included bank bonds and special bonds in the securities eligible for open market operations, aiming to stabilize the financial market. On top of government bonds and government-guaranteed bonds, Article 4 of Regulations on Open Market Operation by the BOK designates monetary stabilization securities, mortgage-backed securities issued by Korea Housing Finance Corporation as eligible for open market operation. When central banks in the US, the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK carried out quantitative easing, they purchased some of the eligible assets stipulated by the central bank law in each jurisdiction. The ECB and the Bank of England that have wider discretion on eligible assets purchased government bonds as well as risky assets such as corporate bonds, a case also found in Japan where the Bank of Japan is buying risky assets not listed in the Bank of Japan Act after acquiring government approval as stipulated in Article 43 of the Bank of Japan Act. By contrast, the US Fed limited its purchase to government bonds and mortgage-backed securities issued by government agencies as restricted in Article 14 of the Federal Reserve Act.

6) In a report on Korea’s possible quantitative easing, Morgan Stanley (2016) projected that the BOK would purchase government bonds and special bonds as large as 2% (KRW 38 trillion) of its GDP per year for two years.

References

Amano, R., Carter, T.J., Leduc, S., 2019, Precautionary Pricing: The Disinflationary Effects of ELB Risk, FRB of San Francisco working paper 2019-26.

Caseli, F., 2017, Did the Exchange Floor Prevent Deflation in the Czech Republic?, IMF working paper WP/17/206.

Eberly, J.C., Stock, J.H., Wright, J.H., 2019, The Federal Reserve’s Current Framework for Monetary Policy: A Review and Assessment, NBER working paper No.26004.

Forbes, K., 2018, Monetary Policy at the Effective Lower Bound: Less Potent? More International? More Sticky? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall Meetings, September 13-14.

Hills, T., Nakata, T., Schmidt, S., 2019, Effective Lower Bound, FRB Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-77.

Kiley, M., Roberts, J.M., 2017, Monetary policy in a low interest rate world, BPEA Conference Drafts, March 23–24.

Lane, P., 2019, Monetary Policy and Below-Target Inflation, at the Bank of Finland conference on Monetary Policy and Future of EMU, July 2.

Mertens, T.M., Williams, J.C, 2019, Monetary Policy Frameworks and the Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 877.

Morgan Stanley, 2016, Why Korea May Be Next in Line for QE.

Smets, F., Wouters, R., 2007, Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycles; A Bayesian DSGE Approach, American Economic Review 97(3), 586-606.

Although monetary policy as well as fiscal policy have long served a stabilizing function in the macroeconomy, there’re questions about future policy effects as major central banks keep their base rates at the lowest levels, aiming to weather the financial crisis and the resultant fall in potential growth in the global economy. Central banks tend to cut interest rates in response to the recession, but they can’t cut the rate indefinitely. Interest rates below a certain level could lead to an abrupt decline in monetary policy effectiveness, capital outflows or other adverse effects. That level is called an effective lower bound. If the base rate is already close to the effective lower bound so that an economy can’t cut the rate further during a recession, this could further worsen the real economic recession. Figure 1 demonstrates the risk inherent in the effective lower bound. If the base rate is close to the 0% effective lower bound, a negative impact on the economy will bring down GDP more drastically, compared to when it’s possible to cut the interest rate without the effective lower bound constraint. Also notable is the risk of the effective lower bound arises even when a rate cut is constrained by the effective lower bound. Recent research findings show that the inflation expectations fall and current inflation stagnates with the recent rise in the possibility of tail risk where declining real interest rates lead to the effective lower bound constraint (Hills, et al., 2019; Amano, et al., 2019; Mertens & Williams, 2019; Kiley & Roberts, 2017).

Important questions related to the effective lower bound are what the level of Korea’s effective lower bound is, and how Korea should react to the effective lower bound. Although the BOK in charge of Korea’s monetary policy has yet to officially mention the level of Korea’s effective lower bound, BOK Governor Juyeol Lee repeatedly stated that the effective lower bound is higher than that of key currency nations given Korea’s capital outflow risk, etc.1) In the same vein, securities firm analysts in a survey forecast that the effective lower bound of Korea’s base rate would be between 0.75% and 1.00%.2) However, capital outflows seem unlikely for the time being given that foreign capital seeking for arbitrage trading is flowing into Korea’s debt market despite the long-term inversion between Korean and US policy rates.

As widely known, some developed economies such as Sweden and Denmark on top of key-currency nations shifted to negative interest rate policies. Among emerging economies, Czech, Chile, and Israel adopted super-low interest rates in the face of severe economic slumps and low inflation. Czech entered the zero interest rate (0.05%) in November 2012, and its economic growth recorded –0.8% and –0.5%, in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In addition, Israel cut the base rate to 0.25% in September 2014, and again to 0.1% in March 2015, which resulted in inflation of –0.6% and –0.5% in 2015 and 2016, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 3, Czech and Israel that kept zero interest rates for years did see capital flowing into the debt markets. Especially, the Czech koruna was under appreciation pressure against the euro amid the European Central Bank’s monetary easing. The super-low interest rate policies in those two nations, on top of the global economic recovery, could be presumably attributable to the economic recovery because after four to five years of super-low rates both countries succeeded to rebound from the recession and low inflation, finally managing to raise their rates.3) Further in-depth research is required to assess the level of the effective lower bound taking into account the impact on financial stability4) and policy paths, etc. But concluding cautiously, the interest rate might be lowered further than market participants now expect if economic conditions deteriorate seriously.

As in developed economies, the BOK has an established framework that could enable unconventional monetary tools if necessary. Already, the BOK uses the Bank Intermediated Lending Support Facility, via which to supply funds at low rates (0.5% to 0.75%) aiming to support new growth and employment, stabilize loans to SMEs, etc. Also it has established tools such as Monetary Policy Reports, Monetary Policy Decisions, and press conferences to better communicate monetary policy with the market. Article 68 of the Bank of Korea Act defines government bonds and the securities designated by the Monetary Policy Board as eligible assets for open market operations. That does away with any legal constraint on the type of eligible securities for the BOK’s quantitative easing program.5) However, further research is needed in the size and eligible securities of quantitative easing, given Korea’s long-term fiscal prudence and the small size of government debt issuance relative to its GDP, as well as the solid demand for government debt among pension funds and insurers.6) It’s worth noting that Czech responded to the zero interest rate with, instead of quantitative easing, policy measures that set up the lower bound exchange rate (27 koruna per euro) and maintained that level via market intervention. It tried to prevent currency from appreciating in seeking to maintain export competiveness, and responded to downward pressure on inflation resulted from declining import prices. Meanwhile, the intervention to purchase the dollar and the euro pushed up the koruna liquidity. More recently, the IMF views positively such policy impacts on the real economy (Caseli, 2017).

It’s true that Korea lacks research and analyses on how to apply unconventional monetary policy tools adopted by the Fed or the ECB to the Korean economy because Korea’s economic condition hasn’t been as bad as requiring those tools thus far. However, in the Monetary Policy for 2020 report, the BOK said it was set to bolster analyses on monetary policy tools other than the interest rate in response to changes in economic conditions. Taking into account a looming structural slowdown in the Korean economy, it is hoped that further studies shed light on a diversified areas such as the changes in the financial markets and the economic system, new monetary policy tools fit for Korea’s economy, and an optimal policy mix with fiscal policy.

1) “It’s uncertain where the effective lower bound is exactly, but it should exist somewhere. And what I can tell you is there’s a shared consensus among Monetary Policy Board members that the effective lower bound is located at a slightly higher level in non-key-currency nations, compared to that in key-currency nations.” (Press conference for monetary policy, Oct. 16, 2019)

2) News1 (Oct. 13, 2019), [Monetary Policy Poll] 2) 50% of analysts surveyed agreed on “Korea’s effective lower bound on the base rate at 0.75%”.

3) As illustrated in Figure 2, fund flows to debt began rising steeply when the economy showed a clear sign of recovery and a rate hike. Forbes (2018) calls the zero-interest rate policy ‘sticky’ in that a rate hike could be delayed because a hinted rate hike after zero-rate policy immediately leads to currency appreciation and import price falls, forming downward pressure on inflation.

4) Czech and Israel had stable household debt to GDP ratios of 30% to 40% during the zero-rate period, whereas the ratios rose in Sweden and other nations whose ratios had been already high before zero-rate policy.

5) At the height of the global financial crisis (Oct. 27, 2018), the BOK temporarily included bank bonds and special bonds in the securities eligible for open market operations, aiming to stabilize the financial market. On top of government bonds and government-guaranteed bonds, Article 4 of Regulations on Open Market Operation by the BOK designates monetary stabilization securities, mortgage-backed securities issued by Korea Housing Finance Corporation as eligible for open market operation. When central banks in the US, the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK carried out quantitative easing, they purchased some of the eligible assets stipulated by the central bank law in each jurisdiction. The ECB and the Bank of England that have wider discretion on eligible assets purchased government bonds as well as risky assets such as corporate bonds, a case also found in Japan where the Bank of Japan is buying risky assets not listed in the Bank of Japan Act after acquiring government approval as stipulated in Article 43 of the Bank of Japan Act. By contrast, the US Fed limited its purchase to government bonds and mortgage-backed securities issued by government agencies as restricted in Article 14 of the Federal Reserve Act.

6) In a report on Korea’s possible quantitative easing, Morgan Stanley (2016) projected that the BOK would purchase government bonds and special bonds as large as 2% (KRW 38 trillion) of its GDP per year for two years.

References

Amano, R., Carter, T.J., Leduc, S., 2019, Precautionary Pricing: The Disinflationary Effects of ELB Risk, FRB of San Francisco working paper 2019-26.

Caseli, F., 2017, Did the Exchange Floor Prevent Deflation in the Czech Republic?, IMF working paper WP/17/206.

Eberly, J.C., Stock, J.H., Wright, J.H., 2019, The Federal Reserve’s Current Framework for Monetary Policy: A Review and Assessment, NBER working paper No.26004.

Forbes, K., 2018, Monetary Policy at the Effective Lower Bound: Less Potent? More International? More Sticky? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall Meetings, September 13-14.

Hills, T., Nakata, T., Schmidt, S., 2019, Effective Lower Bound, FRB Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-77.

Kiley, M., Roberts, J.M., 2017, Monetary policy in a low interest rate world, BPEA Conference Drafts, March 23–24.

Lane, P., 2019, Monetary Policy and Below-Target Inflation, at the Bank of Finland conference on Monetary Policy and Future of EMU, July 2.

Mertens, T.M., Williams, J.C, 2019, Monetary Policy Frameworks and the Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 877.

Morgan Stanley, 2016, Why Korea May Be Next in Line for QE.

Smets, F., Wouters, R., 2007, Shocks and Frictions in US Business Cycles; A Bayesian DSGE Approach, American Economic Review 97(3), 586-606.