Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy Under the Covid-19 Pandemic

Publication date Apr. 09, 2020

Summary

Korea’s government and the Bank of Korea have been acting quickly to alleviate the Covid-19 shocks to the financial markets and the real economy. Against the backdrop, this article sheds light on the role of the BOK in a stable corporate financing market, the BOK’s further actions such as a rate cut to zero and quantitative easing, and a balance between imminent fiscal demand and long-term fiscal soundness. Among others, the BOK is legally limited from purchasing commercial paper and corporate bonds. In the short run, Korea should increase liquidity to support the government’s market stabilization measures, while establishing a legal basis for helping the BOK serve as a lender of last resort in the long run. Amid the looming expectations of a deepening slowdown in the real economy, the future monetary policy directions should be a further cut in the base interest rate and an introduction of quantitative easing. Last but not least, policy authorities need to take a forward-looking position about a one-off fiscal expansion to cope with temporary, not structural shocks. Desirably, future discussion should shift towards how to effectively support households and industries on the verge of crisis, away from controversies around fiscal soundness.

With Covid-19 rapidly spreading to the globe since March 2020, countries around the world, one after another, have restricted people’s movement. As this is raising concerns over a disruption in manufacturing activity as well as a contraction in demand that could dampen corporate earnings, the global stock markets have been in a severe correction. In the meantime, jitters in the corporate bond market have been growing further. It is fortunate that governments and central banks around the world are taking draconian measures they once used during the global financial crisis as part of effort to contain market unrest.

Korea’s market stabilization measures are also in line with global policy action. The Bank of Korea cut its base interest rate, and the parliament approved a supplementary budget to contain the fallout of the virus’s worsening community spread. Also unveiled are government packages to stabilize financial markets and support small business owners and the self-employed, and the Bank of Korea’s liquidity provision plan.1) Because a social consensus was reached on the need for bold policy policy responses, there’s not much to add to discussions on the policy direction. However, it would be worth taking a closer look at a few issues on Korea’s monetary and fiscal policy that is closely linked to uncertainties ahead of Korea’s economic growth path.

1. The BOK’s role in stabilizing the corporate financing market

Amid mounting concerns about Covid-19’s impact on corporate earnings, nations around the globe one after another unveiled economic stimulus packages, with the primary focus placed on helping private sector firms to finance and keep their employees in post. In particular, central banks around the world have stepped up their effort to extend credits for purchasing commercial paper or corporate bonds in their bid to stabilize the corporate financing market. For example, the Fed in the US chose the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) to buy commercial paper of investment-grade firms. The European Central Bank (ECB) followed suit by expanding its asset purchases to non-financial commercial paper, while the Bank of Japan topped up purchases of corporate bonds.2)

The fallout of the pandemic is expected to affect not only small business owners and the self-employed, but also large corporations such as airlines, hotels, petrochemical firms in Korea as well. To address the issue, there’re calls for the BOK to step forward to purchase commercial paper or corporate bonds for the sake of financial stabilization. However, it’s not possible under the current legal framework. Unlike other countries, Korea’s law doesn’t allow the BOK to directly purchase debt issued by non-financial firms. In the US, the Federal Reserve Act grants the Fed the right to provide government-approved emergency lending with no conditions attached to eligible collaterals at a time of crisis. Under the arrangement, a special purpose vehicle established by the Fed buys commercial paper which is used as collaterals for the Fed’s lending to the SPV. This makes an effect of the Fed directly purchasing commercial paper.3) In Europe, the range of securities eligible for ECB open market operations is stipulated not in the European central banking law, but in the ECB guideline,4) which enables ECB to act flexibly in terms of what securities the bank should buy to cope with a financial crisis.5) The Bank of Japan is also purchasing commercial paper, corporate bonds, and even exchange-traded funds and J-REITs because under government authorization the bank is allowed to buy assets that are not in the list of eligible securities for open market operations.6)

On the other hand, the BOK is unable to meet market expectations because it cannot purchase non-financial commercial papers or corporate bonds without a government guarantee. The Bank of Korea Act explicitly bans the BOK from buying debt securities of non-financial firms, but also limits open market operations to a strictly narrow range of securities such as government bonds and government-guaranteed securities, etc.7) Due to the institutional restriction, the BOK’s action to stabilize the corporate financing market in the past was limited to indirect support, e.g., indirectly helping the banking sector replenish capital, or extending special loans to state banks.8) This leaves the Bank of Korea with only two options to ease immediate market unrest: One of them is the BOK’s recently released plan for unlimited liquidity provision via repo operations, and the other is using the bond market stabilization fund established by the government. However, the bond market stabilization fund in Korea is mostly financed by financial institutions. As the coronavirus pandemic could prolong financial unrest, it’s important for Korea to form a legal basis that helps the BOK can serve as a lender of the last resort as does the Fed at a time of financial crisis.

2. A further interest rate cut and quantitative easing by the BOK

To cut it short, the BOK should cut its base interest rate close to the zero-rate level with quantitative easing for Korea’s future growth path and financial market stability. As Fed Chairman Jerome Powell put it, Covid-19’s impact on the real economy is highly uncertain and “unknowable”. Based on a glimpse of recent economic indicators and data from major developed countries, the first-quarter economic growth is forecast to slow significantly due to the on-going community spread dragging down private consumption in Korea, in addition to manufacturing disruptions and declining demand in China. Although production disruptions could subside when China resumes production, the impact of slow consumption is expected to continue. On top of that, the demand contraction in the US and the euro area will slow Korea’s exports, which could linger into the third quarter. Hence, a full recovery is expected to come only after the fourth quarter with a rebound in external demand and in tourism and other industries particularly vulnerable to the outbreak. Assuming this year’s economic growth hitting the mid-zero percent range under such a grim growth path,9) the BOK’s estimated monetary policy reaction function based on past economic data implies Korea’s second-quarter base rate to be around the zero-percent range.

Although a consensus is reached on the need to loosen monetary policy to boost the real economy, there’re still questions about whether the monetary policy path would function well under today’s super-low interest rate environment. Also in doubt is whether the interest rate could be lowered further under the current effective lower bound. However, a cut in interest rates is de facto the only macroeconomic policy tool that could immediately deal with internal and external shocks, especially at a time when key decisions over massive fiscal expansion such as the second round of supplementary budget is hardly likely to be made time-wise. Also, the base interest rate forms a lower bound for short-term credits including commercial paper. Even if the credit path is not functioning properly due to financial unrest, a cut in the base interest rate could, albeit partially, contribute to stabilizing corporate financing. It’s also important to note that the low expectations about a further rate cut could possibly restrain a decline in the yields on long-term bonds including government bonds. With regard to the effective lower bound,10) there’re mounting concerns over capital outflows as the internal-external interest rate differentials are narrowing. The concerns are growing further with the won-dollar exchange rate fluctuating recently. However, such concerns could be ill-founded for two reasons. First, capital inflows to Korea, especially to the bond market, continued under the reversion in the internal-external interest rates of Korea and the US before the Covid-19 pandemic. Second, previous literature reports that the correlation between the internal-external interest rate differentials and capital outflows is insignificant.

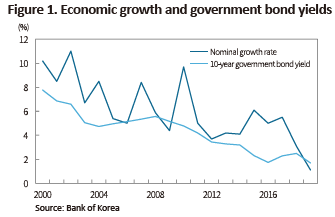

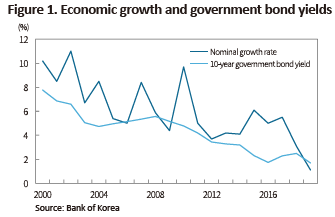

When an interest rate cut seems insufficient to respond to adverse shocks in the real economy, quantitative easing is another monetary policy tool. Given the active political discussions on how to support vulnerable industries and citizens, Korea is expected to see an increase in government bond issuance that could finance the support packages after the general election. Major economies that already unveiled such massive financial support packages are already seeing a rise in their government bond yields. This partly explain the rise in Korea’s government bond yields despite its aggressive cut in the base interest rate. In response to such a market trend, the BOK purchased government bonds on March 19, 2020.

The fallout of the pandemic is highly likely to worsen Korea’s already large household debt as there will be more financing concerns in firms, more unemployment among wage workers, and more bankruptcy among self-employed and small business owners. Under the circumstances, it’s desirable to use quantitative easing to stabilize the market for corporate bonds and bank bonds. Due to Korea’s long-held fiscal stability, its government bond market is small given the size of its real economy. This makes it hard for Korea to follow the footsteps of other central banks to purchase a massive amount of government bond that will expectedly pump liquidity into the financial markets, ease credit restraints, and positively affect private sector portfolios.11) Nevertheless, a central bank’s quantitative easing declaration sends a clear signal to the market about its commitment to stabilize long-term interest rate, which makes the policy more effective. As can be seen in the case of the base interest rate, a cut in government bond yields will in effect lower the floor of the yields on corporate bonds and bank bonds. With regard to this, it’s worth benchmarking the yield curve control adopted by the Bank of Japan and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Unlike quantitative easing that specifies the size of government bond purchases, the yield curve control sets the purchase price with an aim to prevent the government bond yield from moving beyond a target level.12) By directly targeting the government bond yield, the yield curve control could effectively reduce the volatility in the market for corporate bonds and bank bonds that are highly correlated to government bond yields. Another benefit is its effect in reducing the risk of an yield increase that could occur as the government bond yield reaches its de facto floor due to the BOK’s base rate restrained to the effective lower bound. Recently, the RBA decided to control its 3-year government bond yield—an important benchmark in the Australian financial market—at the 0.25% level. It’s worth considering Korea targeting government bonds of a specific maturity, given that 3-year on-the-run corporate yields are a benchmark in Korea’s corporate financing market and 5-year bank yields are a reference rate in household loans. Certainly, a central bank’s explicit and direct role in managing the yield curve is not without risks. This could not only distort pricing of interest rates, but also inflate the balance sheets during the unlimited purchase of government bonds at a target price. Despite those potential setbacks, however, this is a policy alternative worth considering at a time when massive fiscal programs to combat the crisis-like recession are faced with an unintended rise in government bond yields. Such a side effect would not only undermines policy effects but also pose a threat to corporate and household debt.

3. A balance between imminent fiscal demand and long-term fiscal health

During the process of Korea’s recent approval of the supplementary budget, opinions were widely divided between the proponents of fiscal expansion and the opponents prioritizing fiscal soundness, which caused controversies around the budget’s appropriate size. Ironically, the responses to and the fallout from Covid-19 in other countries highlight the importance of fiscal health. A case in point is what happened in countries in Southern Europe. Due to their weak fiscal conditions, they had to cut healthcare budget before the Covid-19 outbreak. As a result, their healthcare system is now unable to handle the exponential growth of patients, which is leading to a meltdown in their healthcare system. Fortunately, Korea has long pursued a fiscal balance, with its debt hovering slightly lower than 40% of GDP. However, NABO warns that the figure could rise steeply to 56.7% of GDP in 2028 amid Korea’s slowed economic growth and population ageing13). If including the debt of public enterprises (KRW 613 trillion, 32% of GDP as of 3Q 2019) that is now excluded from the data, Korea’s national debt in a broader sense will be higher.

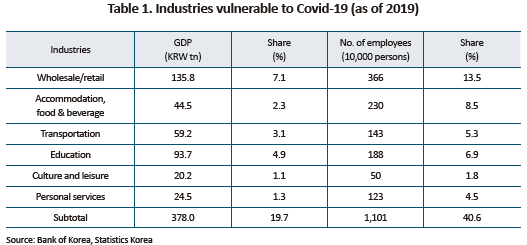

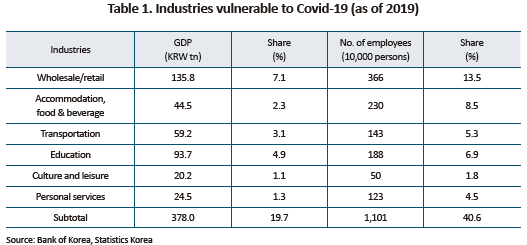

Nevertheless, the fiscal authorities should keep a close eye on the losses cumulating in the service sector that is hit hard by lingering social distancing. As of 2019, the service sector, especially vulnerable to social distancing, is estimated to take up 20% of GDP and 40% of employment in Korea. During the global financial crisis, the impact from lagging external demand was concentrated mainly in the manufacturing sector, whereas the pandemic is expected to give a further blow to the economy because diminishing consumption would adversely affect the service sector that employs a large percentage of workers. This is why major developed countries are launching large-scale fiscal programs in the face of economic hardship under social distancing measures to combat Covid-19.

As the coronavirus pandemic is expected to immensely affect the real economy, there will be a large, albeit temporary, increase in fiscal demand as part of effort to respond to external shocks. However, it’s important to note that such an increase is not structural. Former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers who served during the Clinton administration underscore the role of fiscal policy when the government bond yield is lower than the nominal economic growth. Although the ratio of national debt to GDP could temporarily rise due to a one-off fiscal expansion that is not structural demand, the national debt ratio will stabilize in the long run as long as economic growth (the increasing rate of the denominator) is higher than the government bond yield (the increasing rate of the numerator). Also worth noting is the possibility of enhanced policy effects under the current low-rate environment: Corporate investment becomes less sensitive to the interest rate, and low inflation expectations diminish crowding out that is regarded as one of the side effects of fiscal policy, all of which is positive for policy effectiveness. What’s desirable for now is a focused approach to how to help households and industries on the verge of crisis, setting aside fiscal soundness temporarily for a moment. A useful starting point to deal with the pandemic would be the “timely, targeted, and temporary” principle on fiscal expenditures, which was widely cited during the global financial crisis.

Conclusion

During the European fiscal crisis, then ECB President Mario Draghi declared he would do “whatever it takes” to stop the euro meltdown, based on which he successfully tackled the crisis via massive asset purchases despite the fierce opposition by Germany, the largest economy in the euro area. This has also become the underlying motto of current policy responses by nations around the globe. They believed only a bold commitment to policy actions would be effective in easing unrest among diverse economic entities and thereby would reduce policy costs. Amid growing concerns over the world’s Japanification, it’s important to reflect on the case of Japan where a series of repeated small actions only resulted in snowballing national debt and quantitative easing by the central bank. Hopefully, Korea’s bold monetary and fiscal actions could be a bridge, ushering the households and companies safely into the post-coronavirus era.

1) The BOK’s liquidity provision program unveiled on March 26 was dubbed “Korean-style quantitative easing” by some media. However, this is somewhat different from quantitative easing where a central bank purchases government bonds, etc. As the program title suggests, Korea’s program purchases repo to provide liquidity to financial institutions, which is more similar to the Fed’s primary dealer credit facility (PDCF).

2) Those measures were implemented by the Fed, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan one after another between March 16 and 18, 2020.

3) This is based on section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, which enabled a broad range of government support to the credit market during the global financial crisis, e.g., the CPFF, the bailout package to AIG, etc. Because under such an arrangement the Fed bears the losses from commercial paper an SPV purchases, the US Treasury Department provides credit guarantees via the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF).

4) Guideline of the European Central Bank on the implementation of the Eurosystem monetary policy framework

5) Because euro area capital markets are fragmented across member states and thus have no single government bond market such as the US one, the ECB allows a wide array of assets traded in each member state financial market to be used for open market operations.

6) Article 43 of Bank of Japan Act

7) Article 68 (Open Market Operations) and Article 79 (Transaction Restrictions with Private Individuals) in the Bank of Korea Act

8) In August 2015, the BOK lent KRW 3.43 trillion at a low interest rate of 0.5%, and issued a KRW 3.45 trillion worth of monetary stabilization bonds (at 2.0%), which in effect provided KDB funds as much as the difference between the interest rates in a bid to stabilize the corporate bond market.

9) Caution is necessary for interpreting the result because this is based on one of the possible scenarios. A more detailed projection

will be unveiled in a revision in KCMI outlook in May, 2020.

10) Although a central bank cuts the interest rate in response to a recession, a cut within a certain level would only result in diminishing policy effects or triggering adverse effects such as capital outflows. The threshold is called the effective lower bound of the base interest rate.

11) As of end-2019, Korea?셲 government bond issuance outstanding stood at KRW 696 trillion, 36.4% of nominal GDP. While responding to the global financial crisis, assets in central banks in developed countries increased immensely to roughly 25% of GDP in the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England as of 2015. At the Bank of Japan, assets shot up to 77% of GDP because it had begun quantitative easing even before the global financial crisis.

12) The three rounds of quantitative easing during the global financial crisis and the recent one announced on March 23 are labelled unlimited because the Fed didn’t specify the duration. Technically, however, the programs are limited by a monthly cap on purchases.

13) National Assembly Budget Office, 2019, NABO Medium-Term Fiscal Projection: 2019~2028.

Korea’s market stabilization measures are also in line with global policy action. The Bank of Korea cut its base interest rate, and the parliament approved a supplementary budget to contain the fallout of the virus’s worsening community spread. Also unveiled are government packages to stabilize financial markets and support small business owners and the self-employed, and the Bank of Korea’s liquidity provision plan.1) Because a social consensus was reached on the need for bold policy policy responses, there’s not much to add to discussions on the policy direction. However, it would be worth taking a closer look at a few issues on Korea’s monetary and fiscal policy that is closely linked to uncertainties ahead of Korea’s economic growth path.

1. The BOK’s role in stabilizing the corporate financing market

Amid mounting concerns about Covid-19’s impact on corporate earnings, nations around the globe one after another unveiled economic stimulus packages, with the primary focus placed on helping private sector firms to finance and keep their employees in post. In particular, central banks around the world have stepped up their effort to extend credits for purchasing commercial paper or corporate bonds in their bid to stabilize the corporate financing market. For example, the Fed in the US chose the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) to buy commercial paper of investment-grade firms. The European Central Bank (ECB) followed suit by expanding its asset purchases to non-financial commercial paper, while the Bank of Japan topped up purchases of corporate bonds.2)

The fallout of the pandemic is expected to affect not only small business owners and the self-employed, but also large corporations such as airlines, hotels, petrochemical firms in Korea as well. To address the issue, there’re calls for the BOK to step forward to purchase commercial paper or corporate bonds for the sake of financial stabilization. However, it’s not possible under the current legal framework. Unlike other countries, Korea’s law doesn’t allow the BOK to directly purchase debt issued by non-financial firms. In the US, the Federal Reserve Act grants the Fed the right to provide government-approved emergency lending with no conditions attached to eligible collaterals at a time of crisis. Under the arrangement, a special purpose vehicle established by the Fed buys commercial paper which is used as collaterals for the Fed’s lending to the SPV. This makes an effect of the Fed directly purchasing commercial paper.3) In Europe, the range of securities eligible for ECB open market operations is stipulated not in the European central banking law, but in the ECB guideline,4) which enables ECB to act flexibly in terms of what securities the bank should buy to cope with a financial crisis.5) The Bank of Japan is also purchasing commercial paper, corporate bonds, and even exchange-traded funds and J-REITs because under government authorization the bank is allowed to buy assets that are not in the list of eligible securities for open market operations.6)

On the other hand, the BOK is unable to meet market expectations because it cannot purchase non-financial commercial papers or corporate bonds without a government guarantee. The Bank of Korea Act explicitly bans the BOK from buying debt securities of non-financial firms, but also limits open market operations to a strictly narrow range of securities such as government bonds and government-guaranteed securities, etc.7) Due to the institutional restriction, the BOK’s action to stabilize the corporate financing market in the past was limited to indirect support, e.g., indirectly helping the banking sector replenish capital, or extending special loans to state banks.8) This leaves the Bank of Korea with only two options to ease immediate market unrest: One of them is the BOK’s recently released plan for unlimited liquidity provision via repo operations, and the other is using the bond market stabilization fund established by the government. However, the bond market stabilization fund in Korea is mostly financed by financial institutions. As the coronavirus pandemic could prolong financial unrest, it’s important for Korea to form a legal basis that helps the BOK can serve as a lender of the last resort as does the Fed at a time of financial crisis.

2. A further interest rate cut and quantitative easing by the BOK

To cut it short, the BOK should cut its base interest rate close to the zero-rate level with quantitative easing for Korea’s future growth path and financial market stability. As Fed Chairman Jerome Powell put it, Covid-19’s impact on the real economy is highly uncertain and “unknowable”. Based on a glimpse of recent economic indicators and data from major developed countries, the first-quarter economic growth is forecast to slow significantly due to the on-going community spread dragging down private consumption in Korea, in addition to manufacturing disruptions and declining demand in China. Although production disruptions could subside when China resumes production, the impact of slow consumption is expected to continue. On top of that, the demand contraction in the US and the euro area will slow Korea’s exports, which could linger into the third quarter. Hence, a full recovery is expected to come only after the fourth quarter with a rebound in external demand and in tourism and other industries particularly vulnerable to the outbreak. Assuming this year’s economic growth hitting the mid-zero percent range under such a grim growth path,9) the BOK’s estimated monetary policy reaction function based on past economic data implies Korea’s second-quarter base rate to be around the zero-percent range.

Although a consensus is reached on the need to loosen monetary policy to boost the real economy, there’re still questions about whether the monetary policy path would function well under today’s super-low interest rate environment. Also in doubt is whether the interest rate could be lowered further under the current effective lower bound. However, a cut in interest rates is de facto the only macroeconomic policy tool that could immediately deal with internal and external shocks, especially at a time when key decisions over massive fiscal expansion such as the second round of supplementary budget is hardly likely to be made time-wise. Also, the base interest rate forms a lower bound for short-term credits including commercial paper. Even if the credit path is not functioning properly due to financial unrest, a cut in the base interest rate could, albeit partially, contribute to stabilizing corporate financing. It’s also important to note that the low expectations about a further rate cut could possibly restrain a decline in the yields on long-term bonds including government bonds. With regard to the effective lower bound,10) there’re mounting concerns over capital outflows as the internal-external interest rate differentials are narrowing. The concerns are growing further with the won-dollar exchange rate fluctuating recently. However, such concerns could be ill-founded for two reasons. First, capital inflows to Korea, especially to the bond market, continued under the reversion in the internal-external interest rates of Korea and the US before the Covid-19 pandemic. Second, previous literature reports that the correlation between the internal-external interest rate differentials and capital outflows is insignificant.

When an interest rate cut seems insufficient to respond to adverse shocks in the real economy, quantitative easing is another monetary policy tool. Given the active political discussions on how to support vulnerable industries and citizens, Korea is expected to see an increase in government bond issuance that could finance the support packages after the general election. Major economies that already unveiled such massive financial support packages are already seeing a rise in their government bond yields. This partly explain the rise in Korea’s government bond yields despite its aggressive cut in the base interest rate. In response to such a market trend, the BOK purchased government bonds on March 19, 2020.

The fallout of the pandemic is highly likely to worsen Korea’s already large household debt as there will be more financing concerns in firms, more unemployment among wage workers, and more bankruptcy among self-employed and small business owners. Under the circumstances, it’s desirable to use quantitative easing to stabilize the market for corporate bonds and bank bonds. Due to Korea’s long-held fiscal stability, its government bond market is small given the size of its real economy. This makes it hard for Korea to follow the footsteps of other central banks to purchase a massive amount of government bond that will expectedly pump liquidity into the financial markets, ease credit restraints, and positively affect private sector portfolios.11) Nevertheless, a central bank’s quantitative easing declaration sends a clear signal to the market about its commitment to stabilize long-term interest rate, which makes the policy more effective. As can be seen in the case of the base interest rate, a cut in government bond yields will in effect lower the floor of the yields on corporate bonds and bank bonds. With regard to this, it’s worth benchmarking the yield curve control adopted by the Bank of Japan and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Unlike quantitative easing that specifies the size of government bond purchases, the yield curve control sets the purchase price with an aim to prevent the government bond yield from moving beyond a target level.12) By directly targeting the government bond yield, the yield curve control could effectively reduce the volatility in the market for corporate bonds and bank bonds that are highly correlated to government bond yields. Another benefit is its effect in reducing the risk of an yield increase that could occur as the government bond yield reaches its de facto floor due to the BOK’s base rate restrained to the effective lower bound. Recently, the RBA decided to control its 3-year government bond yield—an important benchmark in the Australian financial market—at the 0.25% level. It’s worth considering Korea targeting government bonds of a specific maturity, given that 3-year on-the-run corporate yields are a benchmark in Korea’s corporate financing market and 5-year bank yields are a reference rate in household loans. Certainly, a central bank’s explicit and direct role in managing the yield curve is not without risks. This could not only distort pricing of interest rates, but also inflate the balance sheets during the unlimited purchase of government bonds at a target price. Despite those potential setbacks, however, this is a policy alternative worth considering at a time when massive fiscal programs to combat the crisis-like recession are faced with an unintended rise in government bond yields. Such a side effect would not only undermines policy effects but also pose a threat to corporate and household debt.

3. A balance between imminent fiscal demand and long-term fiscal health

During the process of Korea’s recent approval of the supplementary budget, opinions were widely divided between the proponents of fiscal expansion and the opponents prioritizing fiscal soundness, which caused controversies around the budget’s appropriate size. Ironically, the responses to and the fallout from Covid-19 in other countries highlight the importance of fiscal health. A case in point is what happened in countries in Southern Europe. Due to their weak fiscal conditions, they had to cut healthcare budget before the Covid-19 outbreak. As a result, their healthcare system is now unable to handle the exponential growth of patients, which is leading to a meltdown in their healthcare system. Fortunately, Korea has long pursued a fiscal balance, with its debt hovering slightly lower than 40% of GDP. However, NABO warns that the figure could rise steeply to 56.7% of GDP in 2028 amid Korea’s slowed economic growth and population ageing13). If including the debt of public enterprises (KRW 613 trillion, 32% of GDP as of 3Q 2019) that is now excluded from the data, Korea’s national debt in a broader sense will be higher.

Nevertheless, the fiscal authorities should keep a close eye on the losses cumulating in the service sector that is hit hard by lingering social distancing. As of 2019, the service sector, especially vulnerable to social distancing, is estimated to take up 20% of GDP and 40% of employment in Korea. During the global financial crisis, the impact from lagging external demand was concentrated mainly in the manufacturing sector, whereas the pandemic is expected to give a further blow to the economy because diminishing consumption would adversely affect the service sector that employs a large percentage of workers. This is why major developed countries are launching large-scale fiscal programs in the face of economic hardship under social distancing measures to combat Covid-19.

During the European fiscal crisis, then ECB President Mario Draghi declared he would do “whatever it takes” to stop the euro meltdown, based on which he successfully tackled the crisis via massive asset purchases despite the fierce opposition by Germany, the largest economy in the euro area. This has also become the underlying motto of current policy responses by nations around the globe. They believed only a bold commitment to policy actions would be effective in easing unrest among diverse economic entities and thereby would reduce policy costs. Amid growing concerns over the world’s Japanification, it’s important to reflect on the case of Japan where a series of repeated small actions only resulted in snowballing national debt and quantitative easing by the central bank. Hopefully, Korea’s bold monetary and fiscal actions could be a bridge, ushering the households and companies safely into the post-coronavirus era.

1) The BOK’s liquidity provision program unveiled on March 26 was dubbed “Korean-style quantitative easing” by some media. However, this is somewhat different from quantitative easing where a central bank purchases government bonds, etc. As the program title suggests, Korea’s program purchases repo to provide liquidity to financial institutions, which is more similar to the Fed’s primary dealer credit facility (PDCF).

2) Those measures were implemented by the Fed, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan one after another between March 16 and 18, 2020.

3) This is based on section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, which enabled a broad range of government support to the credit market during the global financial crisis, e.g., the CPFF, the bailout package to AIG, etc. Because under such an arrangement the Fed bears the losses from commercial paper an SPV purchases, the US Treasury Department provides credit guarantees via the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF).

4) Guideline of the European Central Bank on the implementation of the Eurosystem monetary policy framework

5) Because euro area capital markets are fragmented across member states and thus have no single government bond market such as the US one, the ECB allows a wide array of assets traded in each member state financial market to be used for open market operations.

6) Article 43 of Bank of Japan Act

7) Article 68 (Open Market Operations) and Article 79 (Transaction Restrictions with Private Individuals) in the Bank of Korea Act

8) In August 2015, the BOK lent KRW 3.43 trillion at a low interest rate of 0.5%, and issued a KRW 3.45 trillion worth of monetary stabilization bonds (at 2.0%), which in effect provided KDB funds as much as the difference between the interest rates in a bid to stabilize the corporate bond market.

9) Caution is necessary for interpreting the result because this is based on one of the possible scenarios. A more detailed projection

will be unveiled in a revision in KCMI outlook in May, 2020.

10) Although a central bank cuts the interest rate in response to a recession, a cut within a certain level would only result in diminishing policy effects or triggering adverse effects such as capital outflows. The threshold is called the effective lower bound of the base interest rate.

11) As of end-2019, Korea?셲 government bond issuance outstanding stood at KRW 696 trillion, 36.4% of nominal GDP. While responding to the global financial crisis, assets in central banks in developed countries increased immensely to roughly 25% of GDP in the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England as of 2015. At the Bank of Japan, assets shot up to 77% of GDP because it had begun quantitative easing even before the global financial crisis.

12) The three rounds of quantitative easing during the global financial crisis and the recent one announced on March 23 are labelled unlimited because the Fed didn’t specify the duration. Technically, however, the programs are limited by a monthly cap on purchases.

13) National Assembly Budget Office, 2019, NABO Medium-Term Fiscal Projection: 2019~2028.