OPINION

2020 Apr/22

Impacts of Covid-19 on Corporate Financing in Korea

Apr. 22, 2020

PDF

- Summary

- The Covid-19 pandemic is imposing a tremendous impact on the real economy and the financial markets. The global economy is slowing down with the financial markets fluctuating wildly. In Korea, concerns about a slowdown in the real economy and a crunch in the corporate financing market put the bond market and the money market into instability. In response, Korea’s government unveiled a series of broad-ranged measures that include almost all market stabilization measures available.

Nevertheless, the lingering uncertainty from the epidemic could prolong the instability in the corporate financing market. Higher investor sensitivity to credit risk could make it harder for issuers to refinance their credit bonds. Also, many firms with decreasing corporate earnings are expected to see a downgrade in their credit ratings, which could lead to a crunch in the credit bond market. Another area of concern is the possibility where the crunch keeps lingering in the money market. In the long run, rising yields could put higher upward pressure on financing costs. All of those circumstances require supplementary policy actions based on a thorough monitoring on the risk factors in the corporate financing market.

Covid-19 has been raising uncertainties in financing of financial and non-financial firms in Korea. With the credit bond issuance turning to negative territory, Korea’s money market is also showing signs of a crunch. On top of that, there is a continuous increase in both long-term yields and credit spreads. Against the backdrop, this article tries to explore the risk factors from the Covid-19 pandemic for the domestic and global corporate financing markets.

Global bond markets under Covid-19

With the spread of Covid-19, bond markets and money markets in developed countries have recorded high volatility. Before the pandemic declaration, the yields on government bonds had been on a downward trend amid stronger appetite for safe assets. However, long-term government bond yields have been rising continuously despite a cut in the policy rate since the pandemic was declared. In the US, 10-year Treasury yields kept rising from 0.599% on March 9 to 1.183% on March 18. Such a rise in long-term government bond yields was also observed in other countries such as the UK, Germany, and Japan after the pandemic declaration. Accordingly, the long-short spread in many countries is drastically widening.

Also rising is the credit spread. In the US, the yield spread between AA-rated corporate bonds and Treasury securities had been hovering around 20bp until mid-February before abruptly rising to 200bp at the end of March, 2020. Europe also saw its credit spread widening from 50bp to 150bp. The high-yield bond market is also wildly fluctuating in the US. Although the high-yield spread had remained around 200bp before the pandemic declaration, it soared to 837bp on March 21 after the declaration. High-yield bonds are also contracting in size. The iShares iBoxx ETF, the largest high-yield ETF, recorded a $3.9 billion net outflow at the end of February, the largest outflow ever after 2010.

Another area of concern is the deepening liquidity crunch in the money market. With rising credit risk in the corporate sector and falling sales in funds investing in commercial paper (CP), the US CP market is seeing a crunch where the issuance falls and the yield increases. As more and more firms face with difficulties in financing via CP, they are flocking to bank credit lines. This is imposing an additional financing burden on banks.

As financial markets see a deepening crunch amid Covid-19, countries around the globe have aggressively cut their key interest rate with the aim to alleviate debtors’ financial burden and boost the economy. For example, the US had hold an emergence Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on March 3, 2020, and cut its key interest rate by 50bp (1.00% to 1.25%), which was quickly followed by another emergency meeting for a further rate cut of 100bp on March 15. Other countries including the UK, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Malaysia also followed suit to decrease their policy interest rate. While expanding liquidity provision on one side, the US is also turning to fiscal policy as part of market stabilization effort. On March 15, it unveiled a quantitative easing program worth $700 billion ($500 billion in government bonds and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities). Such a bold announcement, however, could not quell market unrest, which led to aggressive stimulus plans on March 23. The plans included a series of actions such as unlimited purchases of Treasury securities and MBS, establishing new facilities for liquidity provision to corporate bonds as well as for small- and medium-sized businesses.

On another front, Europe unveiled plans to carry out quantitative easing policy by expanding its purchases of government bonds and easing long-term loan conditions, etc. However, it held out its policy rate cut because it has less room to another rate cut under its long-held negative interest rate environment.

Increasing volatility in Korea’s corporate financing market

Amid the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s corporate financing market also showed signs of a crunch. With the issuance of corporate bonds declining since March 2020, the overall condition in the primary market deteriorated severely from mid-March. Some investment-grade issuers failed to attract investors during its book building process. Accordingly, corporate bonds outstanding has stagnated since March despite its rapid growth during the pre-pandemic period. Also notable is a significant increase in uncertainty in the money market. As securities firms are turning increasingly to short-term instruments for financing, the market sees CP yields soaring and a market crunch deteriorating.

In response to the economic recession and liquidity crunch amid the Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s government and the Bank of Korea released a wide array of policy actions aiming to stabilize the financial markets and to revitalize the economy. On March 16, the Monetary Policy Board held an emergency meeting and cut its base rate by 50bp to 0.75%. This is a coordinated policy action in line with the policy stance of other major economies amid financial market unrest. Slightly later on March 20, Korea also signed a bilateral currency swap worth $60 billion with the US. Before that, the government already announced its biggest-ever supplementary budget worth KRW 11.7 trillion on March 17. With higher fiscal expenditures, the government plans to make its disease control system stronger, to provide more support to SMEs, small merchants and the self-employed, and to help boost the regional economy.

To alleviate financial shocks from the Covid-19 epidemic, the government unveiled a series of financial market stabilization measures on March 24, including KRW 58.3 trillion for financing support for businesses via policy financing and loan guarantees, KRW 41.8 trillion for stabilizing the corporate bond and money markets. This will be supplemented by a KRW 10 trillion bond market stabilization fund that will receive another KRW 10 trillion. To support the issuance of corporate bonds, the plan will introduce primary collateralized bond obligations (P-CBO) worth KRW 6.7 trillion as well as a fast track refinancing system for corporate bonds. Under the measures, the Korea Development Bank will purchase KRW 1.9 trillion worth of refinancing issue of corporate bonds.

As seen above, the financial market stabilization measures are all-out efforts that mobilize almost every possible tool in hand to stabilize the market and the economy. Such an immediate, large-scale, and comprehensive response is viewed as appropriate at a time when the Covid-19 epidemic is pushing the overall real economy into a contraction with a looming possibility of a longer-term recession.

Assessing risk factors in corporate financing

In spite of the bold measures, the risk factors surrounding the corporate financing market could linger for the time being if the Covid-19 epidemic lengthens further, which requires preparedness.

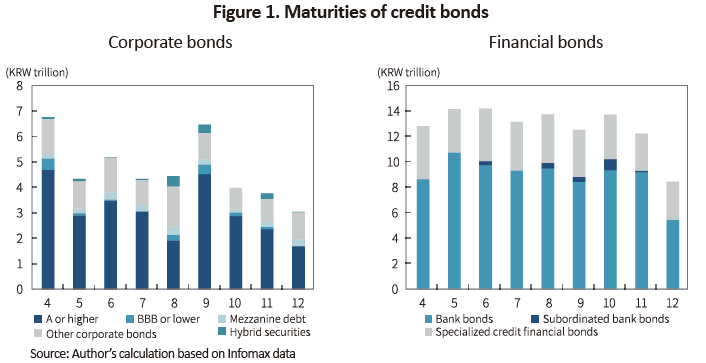

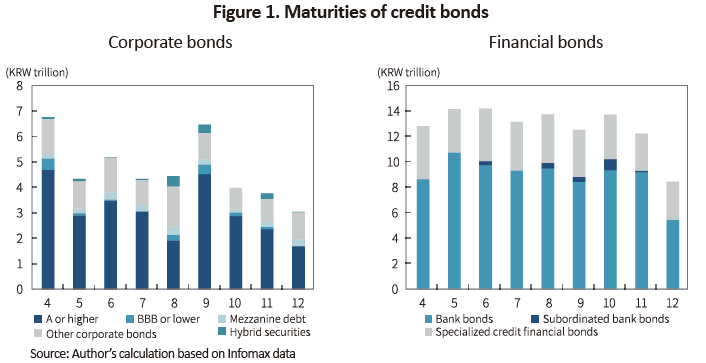

Among others, the market should be alert to the risk of a crunch in refinancing of credit bonds. The size of corporate bonds that mature between April and December 2020 reaches KRW 42.4 trillion, and the figure is KRW 114.9 trillion for financial bonds such as bank bonds and credit finance bonds. A great number of credit bonds are to mature in April, and large-scale financial bonds in May.

The problem is the instability in the credit bond market could make refinancing of low-rated credit bonds more difficult. Among the corporate bonds that will mature this year, KRW 1.5 trillion is rated BBB or lower, KRW 1.9 trillion is in mezzanine debt, and KRW 10.3 trillion is in other corporate debt including privately placed corporate bonds. Although the share of publicly offered corporate bonds rated BBB or lower decreased significantly in Korea’s corporate bond market, privately placed corporate bonds increased their proportion after 2017. In general, privately placed corporate bonds are primarily issued by low-rated issuers and invested by private funds, securities firms, specialized credit financial businesses, banks, etc. With increased credit risk in the market, investors are scaling down their investments in low-rated bonds. Not only will this make it difficult for the issuers to refinance those debt, it will also add significant repayment burden to the issuers.

In addition, the issuers of mezzanine debt will be faced with higher repayment burden. Mezzanine debt is one of the hybrid securities that is converted to stocks or that grants a right to purchase stocks under certain terms and conditions. Basically, mezzanine debt assumes that the stock price will rise in the future. But if the stock price plunges, the investor will have to repay the unconverted debt at maturity. Because of the recent plunge in stock prices, it’s possible for most mezzanine debt maturing this year to remain unconverted, and thus to be repaid at maturity. This heightens the likelihood of distress in mezzanine debt issuers.

If the Covid-19 epidemic lingers, this also could affect refinancing of some financial bonds and investment-grade corporate bonds in the long run. In particular, the size of specialized credit financial bonds maturing this year amounts to KRW 32.4 trillion. Should Korea’s economic recession come to pass due to the further spread of Covid-19, this will elevate delinquencies in consumer financing. An event like this will eventually have an adverse impact on specialized credit financial institutions whose refinancing tends to be quite large in size. If lengthening further, the Covid-19 pandemic will also lead to a significant slowdown in issuance of high-rated corporate bonds.

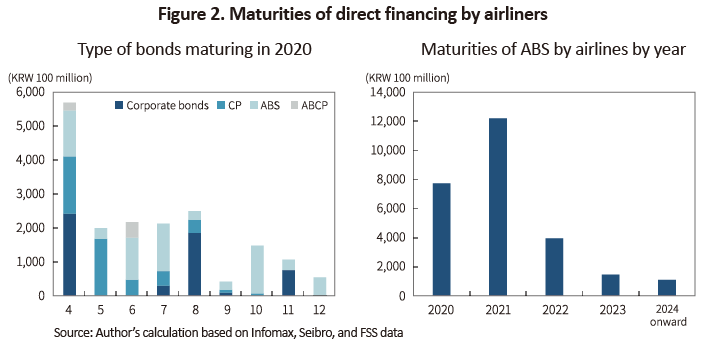

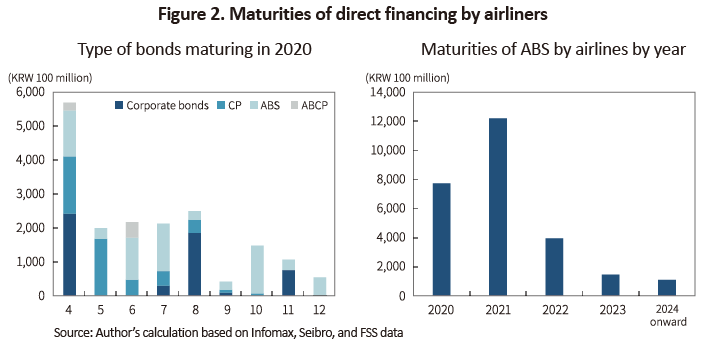

Another fallout expected from Covid-19 is the impact on corporate earnings, which could lead to a series of rating downgrades in the private sector. In the short run, tourism, leisure, wholesale and retail, and airlines are already seeing a direct impact from suspended operations. Accordingly, credit rating agencies in Korea put the affected firms on its watch list1) for a possible downgrade, and already adjusted their rating outlook2) on those firms. Among other industries, airlines are suffering from a much larger shock than expected, and will see their liquidity conditions deteriorating further. Korea’s airline industry holds a total of KRW 1.8 trillion in debt raised from the capital markets that should be repaid from April to December 2020. The debt consists of bonds (30.1%), short-term instruments (26.7%), and asset-backed securities (43.2%). What’s particularly problematic is the ABS based on future ticket sales. A downgrade in the issuer’s credit rating and a fall in airfares larger than a certain threshold are early amortization triggers that force the issuer to repay the whole debt before maturity. This highlights the need for immediate financial support to the industries that are vulnerable to short-term fallout from Covid-19. In the long run, the pandemic is likely to impose impacts on almost all industrial sectors including semiconductor, petrochemical, oil refining, automobile, retail, wholesale, and distribution industries. Consequently, many financial and non-financial firms suffering from deteriorating earnings will see their credit rating be adjusted downward in the latter half of this year. In particular, a rating downgrade of a firm that issued a large volume of bonds could be problematic as this could spark excessive market reaction, which will possibly result in a market crunch.

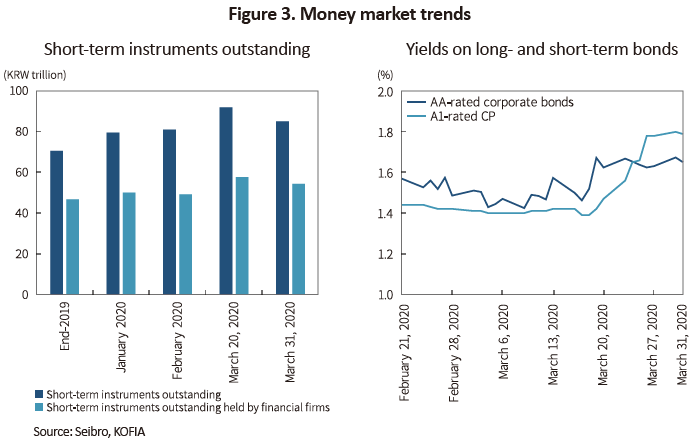

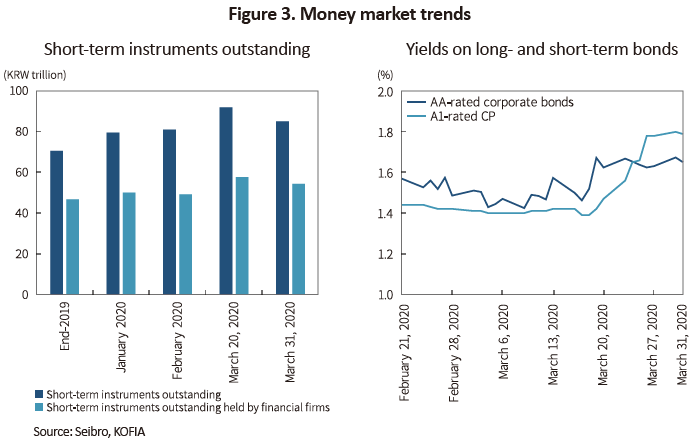

The signs of a market crunch triggered by Covid-19 first emerged in the money market. The outstanding amount of short-term instruments including CP and electronic short-term bonds (ESTB) by financial and non-financial firms stood at KRW 80.8 trillion in end-April 2020. It increased significantly to KRW 91.7 trillion on March 20 before diminishing slightly to KRW 84.9 trillion at the end of March. Such a drastic change stemmed from the skyrocketing volatility in short-term financing by securities firms. Financial firms including securities firms saw their short-term instruments outstanding rapidly rise from KRW 49 trillion in end-February to KRW 57.6 trillion on March 20, before shrinking back to KRW 54.3 trillion in end-March. As many global indexes—underlying assets of equity-linked securities—plunged recently, large securities firms in Korea came to face with increased margin calls on derivatives positions they held for the purpose of hedging. In response, they abruptly increased shot-term financing. The signs of the money market crunch abated somewhat after the government released its policy to expand liquidity provision to the money market. However, a crunch is likely again if the pandemic lengthens further.

The higher money market volatility also dramatically pushed up money market yields. The increase first began on March 20, 2020. As of March 25, the CP yield remained even higher than the mark-to-market yield on 3-year, AA-rated corporate bonds.

What past financial crises teach us is that the money market first shows signs of unrest before an all-out crisis begins. By nature, the money market reacts sensitively to short-term shocks. Because any unrest in the money market could further spread to the overall financial markets, it’s important to channel more efforts to stabilize the money market.

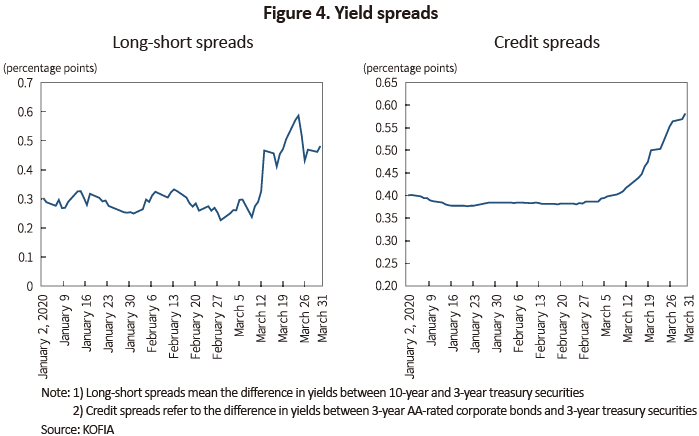

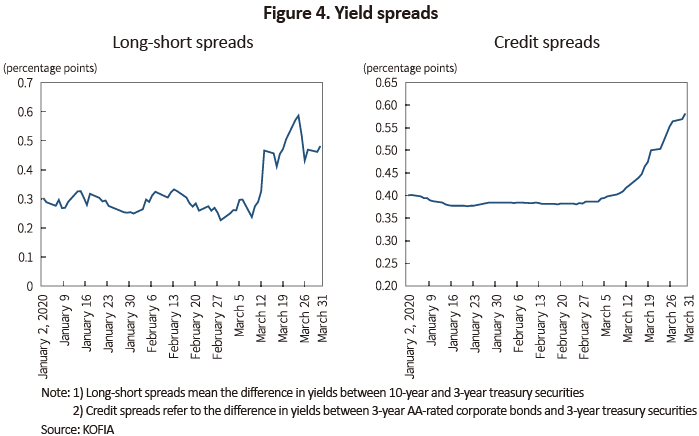

Covid-19 is highly likely to ramp up pressure on yield increases in the long run. Hence, firms should brace for rising costs of financing. The yield spread between long-term and short-term treasury securities climbed abruptly in March 2020. It first rose from 22bp in end-February to 58.7bp on March 24 before slightly falling to 48.2bp in end-March. It seems that the financial market stabilization measures on March 24 helped the long-short spread to decline slightly. However, there’re several factors that could lead to a further yield increase. First, rising government spending on mitigating Covid-19’s fallout will result in a tremendous increase in government bond issuance, and this will be a burden from the supply side. From the demand side, the shrinking financial market could dampen investment demand for government bonds despite the rising appetite for safer assets. In short, an increase in government bond issuance could serve to increase government bond yields, particularly long-term ones.

Furthermore, credit spreads are expected to rise due to a crunch in the credit bond market. Credit spreads kept rising to reach 58.1bp in end-March from 38.6bp in end-February. It’s possible for credit spreads to widen further in the near future as investors become even more sensitive to credit worthiness amid more rating downgrades in corporate bonds.

Such an upward trend in yields is surely expected to push up financing costs of firms. With long-short and credit spreads rising further, the maturities of corporate bonds and financial bonds are forecast to be shortened compared to now.

Devising flexible responses to changes

The rising uncertainty in the corporate financing market amid the Covid-19 pandemic necessitates more than ever before the need for flexible responses to market conditions. Among others, stronger policy support is required to cope up with corporate financing needs. It’s advisable that the Bank of Korea proactively consider purchasing investment-grade corporate bonds as do central banks in other countries. Also necessary is further market stabilizing effort to broaden the range of eligible securities for the bond market stabilization fund that has been introduced to ease a potential credit crunch.

On top of that, flexibility should be a policy priority so that firms suffering from a rating downgrade and falling earnings can refinance their debt seamlessly. What’s necessary in particular is a policy action, e.g., lowering credit risk via emergency liquidity provision to the industry and firms directly affected by Covid-19’s fallout. Because corporate bonds rated A or lower can’t be included in the bond market stabilization fund, it’s worth considering establishing a fund that is specialized for corporate bonds and is granted tax benefits. Such a fund can purchase a broader range of corporate bonds at market prices, and its tax benefits help increase incentives for investments. By absorbing more liquidity to address a market crunch, this will in the long run facilitate the corporate fund market as well.

Last but not least, it’s important to implement a policy aiming to stabilize the money market. Because a money market crunch can spread to the overall market, a bold action is needed toward market stabilization. Also necessary alongside with that action is a timely policy tool to stabilize yields based on a thorough monitoring on yield conditions. An option particularly worth considering toward that end is a policy for stabilizing government bond yields that is also being implemented by major central banks.

1) This is a rating scheme to signal the beginning of a review process that could possibly lead to a short-term rating adjustment due to an event affecting the credit profile of a firm.

2) This refers to an agency’s current outlook on the direction of a firm’s credit rating in one to two years.

Global bond markets under Covid-19

With the spread of Covid-19, bond markets and money markets in developed countries have recorded high volatility. Before the pandemic declaration, the yields on government bonds had been on a downward trend amid stronger appetite for safe assets. However, long-term government bond yields have been rising continuously despite a cut in the policy rate since the pandemic was declared. In the US, 10-year Treasury yields kept rising from 0.599% on March 9 to 1.183% on March 18. Such a rise in long-term government bond yields was also observed in other countries such as the UK, Germany, and Japan after the pandemic declaration. Accordingly, the long-short spread in many countries is drastically widening.

Also rising is the credit spread. In the US, the yield spread between AA-rated corporate bonds and Treasury securities had been hovering around 20bp until mid-February before abruptly rising to 200bp at the end of March, 2020. Europe also saw its credit spread widening from 50bp to 150bp. The high-yield bond market is also wildly fluctuating in the US. Although the high-yield spread had remained around 200bp before the pandemic declaration, it soared to 837bp on March 21 after the declaration. High-yield bonds are also contracting in size. The iShares iBoxx ETF, the largest high-yield ETF, recorded a $3.9 billion net outflow at the end of February, the largest outflow ever after 2010.

Another area of concern is the deepening liquidity crunch in the money market. With rising credit risk in the corporate sector and falling sales in funds investing in commercial paper (CP), the US CP market is seeing a crunch where the issuance falls and the yield increases. As more and more firms face with difficulties in financing via CP, they are flocking to bank credit lines. This is imposing an additional financing burden on banks.

As financial markets see a deepening crunch amid Covid-19, countries around the globe have aggressively cut their key interest rate with the aim to alleviate debtors’ financial burden and boost the economy. For example, the US had hold an emergence Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on March 3, 2020, and cut its key interest rate by 50bp (1.00% to 1.25%), which was quickly followed by another emergency meeting for a further rate cut of 100bp on March 15. Other countries including the UK, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Malaysia also followed suit to decrease their policy interest rate. While expanding liquidity provision on one side, the US is also turning to fiscal policy as part of market stabilization effort. On March 15, it unveiled a quantitative easing program worth $700 billion ($500 billion in government bonds and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities). Such a bold announcement, however, could not quell market unrest, which led to aggressive stimulus plans on March 23. The plans included a series of actions such as unlimited purchases of Treasury securities and MBS, establishing new facilities for liquidity provision to corporate bonds as well as for small- and medium-sized businesses.

On another front, Europe unveiled plans to carry out quantitative easing policy by expanding its purchases of government bonds and easing long-term loan conditions, etc. However, it held out its policy rate cut because it has less room to another rate cut under its long-held negative interest rate environment.

Increasing volatility in Korea’s corporate financing market

Amid the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s corporate financing market also showed signs of a crunch. With the issuance of corporate bonds declining since March 2020, the overall condition in the primary market deteriorated severely from mid-March. Some investment-grade issuers failed to attract investors during its book building process. Accordingly, corporate bonds outstanding has stagnated since March despite its rapid growth during the pre-pandemic period. Also notable is a significant increase in uncertainty in the money market. As securities firms are turning increasingly to short-term instruments for financing, the market sees CP yields soaring and a market crunch deteriorating.

In response to the economic recession and liquidity crunch amid the Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s government and the Bank of Korea released a wide array of policy actions aiming to stabilize the financial markets and to revitalize the economy. On March 16, the Monetary Policy Board held an emergency meeting and cut its base rate by 50bp to 0.75%. This is a coordinated policy action in line with the policy stance of other major economies amid financial market unrest. Slightly later on March 20, Korea also signed a bilateral currency swap worth $60 billion with the US. Before that, the government already announced its biggest-ever supplementary budget worth KRW 11.7 trillion on March 17. With higher fiscal expenditures, the government plans to make its disease control system stronger, to provide more support to SMEs, small merchants and the self-employed, and to help boost the regional economy.

To alleviate financial shocks from the Covid-19 epidemic, the government unveiled a series of financial market stabilization measures on March 24, including KRW 58.3 trillion for financing support for businesses via policy financing and loan guarantees, KRW 41.8 trillion for stabilizing the corporate bond and money markets. This will be supplemented by a KRW 10 trillion bond market stabilization fund that will receive another KRW 10 trillion. To support the issuance of corporate bonds, the plan will introduce primary collateralized bond obligations (P-CBO) worth KRW 6.7 trillion as well as a fast track refinancing system for corporate bonds. Under the measures, the Korea Development Bank will purchase KRW 1.9 trillion worth of refinancing issue of corporate bonds.

As seen above, the financial market stabilization measures are all-out efforts that mobilize almost every possible tool in hand to stabilize the market and the economy. Such an immediate, large-scale, and comprehensive response is viewed as appropriate at a time when the Covid-19 epidemic is pushing the overall real economy into a contraction with a looming possibility of a longer-term recession.

Assessing risk factors in corporate financing

In spite of the bold measures, the risk factors surrounding the corporate financing market could linger for the time being if the Covid-19 epidemic lengthens further, which requires preparedness.

Among others, the market should be alert to the risk of a crunch in refinancing of credit bonds. The size of corporate bonds that mature between April and December 2020 reaches KRW 42.4 trillion, and the figure is KRW 114.9 trillion for financial bonds such as bank bonds and credit finance bonds. A great number of credit bonds are to mature in April, and large-scale financial bonds in May.

The problem is the instability in the credit bond market could make refinancing of low-rated credit bonds more difficult. Among the corporate bonds that will mature this year, KRW 1.5 trillion is rated BBB or lower, KRW 1.9 trillion is in mezzanine debt, and KRW 10.3 trillion is in other corporate debt including privately placed corporate bonds. Although the share of publicly offered corporate bonds rated BBB or lower decreased significantly in Korea’s corporate bond market, privately placed corporate bonds increased their proportion after 2017. In general, privately placed corporate bonds are primarily issued by low-rated issuers and invested by private funds, securities firms, specialized credit financial businesses, banks, etc. With increased credit risk in the market, investors are scaling down their investments in low-rated bonds. Not only will this make it difficult for the issuers to refinance those debt, it will also add significant repayment burden to the issuers.

In addition, the issuers of mezzanine debt will be faced with higher repayment burden. Mezzanine debt is one of the hybrid securities that is converted to stocks or that grants a right to purchase stocks under certain terms and conditions. Basically, mezzanine debt assumes that the stock price will rise in the future. But if the stock price plunges, the investor will have to repay the unconverted debt at maturity. Because of the recent plunge in stock prices, it’s possible for most mezzanine debt maturing this year to remain unconverted, and thus to be repaid at maturity. This heightens the likelihood of distress in mezzanine debt issuers.

If the Covid-19 epidemic lingers, this also could affect refinancing of some financial bonds and investment-grade corporate bonds in the long run. In particular, the size of specialized credit financial bonds maturing this year amounts to KRW 32.4 trillion. Should Korea’s economic recession come to pass due to the further spread of Covid-19, this will elevate delinquencies in consumer financing. An event like this will eventually have an adverse impact on specialized credit financial institutions whose refinancing tends to be quite large in size. If lengthening further, the Covid-19 pandemic will also lead to a significant slowdown in issuance of high-rated corporate bonds.

The higher money market volatility also dramatically pushed up money market yields. The increase first began on March 20, 2020. As of March 25, the CP yield remained even higher than the mark-to-market yield on 3-year, AA-rated corporate bonds.

What past financial crises teach us is that the money market first shows signs of unrest before an all-out crisis begins. By nature, the money market reacts sensitively to short-term shocks. Because any unrest in the money market could further spread to the overall financial markets, it’s important to channel more efforts to stabilize the money market.

Furthermore, credit spreads are expected to rise due to a crunch in the credit bond market. Credit spreads kept rising to reach 58.1bp in end-March from 38.6bp in end-February. It’s possible for credit spreads to widen further in the near future as investors become even more sensitive to credit worthiness amid more rating downgrades in corporate bonds.

Such an upward trend in yields is surely expected to push up financing costs of firms. With long-short and credit spreads rising further, the maturities of corporate bonds and financial bonds are forecast to be shortened compared to now.

The rising uncertainty in the corporate financing market amid the Covid-19 pandemic necessitates more than ever before the need for flexible responses to market conditions. Among others, stronger policy support is required to cope up with corporate financing needs. It’s advisable that the Bank of Korea proactively consider purchasing investment-grade corporate bonds as do central banks in other countries. Also necessary is further market stabilizing effort to broaden the range of eligible securities for the bond market stabilization fund that has been introduced to ease a potential credit crunch.

On top of that, flexibility should be a policy priority so that firms suffering from a rating downgrade and falling earnings can refinance their debt seamlessly. What’s necessary in particular is a policy action, e.g., lowering credit risk via emergency liquidity provision to the industry and firms directly affected by Covid-19’s fallout. Because corporate bonds rated A or lower can’t be included in the bond market stabilization fund, it’s worth considering establishing a fund that is specialized for corporate bonds and is granted tax benefits. Such a fund can purchase a broader range of corporate bonds at market prices, and its tax benefits help increase incentives for investments. By absorbing more liquidity to address a market crunch, this will in the long run facilitate the corporate fund market as well.

Last but not least, it’s important to implement a policy aiming to stabilize the money market. Because a money market crunch can spread to the overall market, a bold action is needed toward market stabilization. Also necessary alongside with that action is a timely policy tool to stabilize yields based on a thorough monitoring on yield conditions. An option particularly worth considering toward that end is a policy for stabilizing government bond yields that is also being implemented by major central banks.

1) This is a rating scheme to signal the beginning of a review process that could possibly lead to a short-term rating adjustment due to an event affecting the credit profile of a firm.

2) This refers to an agency’s current outlook on the direction of a firm’s credit rating in one to two years.