Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Concerns about Liquidity Shortage in Korea’s CP and ESTB Markets Under Covid-19

Publication date Apr. 22, 2020

Summary

Even when a firm cannot finance itself in the corporate bond market, it can often tap into shorter-term instruments such as commercial paper and electronic short-term bonds. This is why a default tends to hit the CP and ESTB markets first before it grows to a crisis and quickly spreads into the overall corporate bond market. Given this particular nature of CP and ESTB markets, it’s critical to closely monitor the prices and fund flows in those markets in times of crisis such as now. Should any unrest increase abruptly, policy authorities need to ensure that liquidity is immediately provided for stabilizing the market.

Given the size of CP and ESTB outstanding, it’s hard to see the liquidity in those markets drying up seriously. However, in terms of yields-another price indicator, there is an evident contraction in market liquidity. As of April 1, 2020, the yields on A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB remained 127bp and 148bp higher than the base interest rate, which increased concerns about short-term corporate financing. What’s worrisome in particular is that an absolutely large part of CP and ESTB is issued by financial and insurance firms. More specifically, the two sub-sectors take up 63.5% of CP, 59.3% of ESTB, and almost all asset-backed CP and asset-backed ESTB in terms of the amount outstanding. This implies that the financial sector will bear the largest brunt of any potential liquidity crunch in the CP and ESTB markets.

Korea’s March 24 financial market stabilization measures include a CP and ESTB purchase program that is expected to help stabilize the corporate bond and money markets. Such a policy action is viewed as appropriate given the roles of CP and ESTB in corporate financing. However, some details on management principles may need adjusting for the program to fully achieve intended policy effects.

Given the size of CP and ESTB outstanding, it’s hard to see the liquidity in those markets drying up seriously. However, in terms of yields-another price indicator, there is an evident contraction in market liquidity. As of April 1, 2020, the yields on A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB remained 127bp and 148bp higher than the base interest rate, which increased concerns about short-term corporate financing. What’s worrisome in particular is that an absolutely large part of CP and ESTB is issued by financial and insurance firms. More specifically, the two sub-sectors take up 63.5% of CP, 59.3% of ESTB, and almost all asset-backed CP and asset-backed ESTB in terms of the amount outstanding. This implies that the financial sector will bear the largest brunt of any potential liquidity crunch in the CP and ESTB markets.

Korea’s March 24 financial market stabilization measures include a CP and ESTB purchase program that is expected to help stabilize the corporate bond and money markets. Such a policy action is viewed as appropriate given the roles of CP and ESTB in corporate financing. However, some details on management principles may need adjusting for the program to fully achieve intended policy effects.

With the rapid spread and high mortality rate, Covid-19 that has been shaking up the global economy for months is regarded as one of the greatest event risks1) in the 21st century. A natural disaster, another common event risk, comes in diverse forms such as earthquakes, typhoons, and forest fires. It usually destroys physical capital to inflict economic damages on the financial markets. More often than not, a geopolitical crisis involves a destruction of not only physical capital but also human capital, adversely affecting the global trade environment. By contrast, an epidemic has a more diverse and complex path via which to impose a shock on the global economy. First, a destruction of human capital seriously contracts production as well as consumption activities. In a modern economy where goods and services are produced and consumed via a global value chain, an epidemic that is not properly contained at the beginning could easily spread throughout the globe. That will destroy human capital on a global scale, triggering trades to fall, production and consumption to contract severely, and businesses to suffer. If it takes longer to develop a fundamental solution such as vaccine and treatment, more businesses will be bankrupt, spreading the real economic crisis into every area in the economy.

As such, Covid-19, already in the pandemic level, is expected to impose a devastating impact on the global economy. Already, negative first-quarter growth in major developed economies is a consensus, and their second-quarter growth is forecast to be worse. On top of that, experts are putting off their estimated timing of the end of the pandemic as well as an economic rebound. Under the circumstances, all economic capabilities should be concentrated in preventing bankruptcy and therefore minimizing economic shocks. Bankruptcy usually causes massive layoffs, thereby diminishing consumption and triggering a chain reaction on relevant industries and firms. This could evolve into a more serious crisis. Hence, the government should quickly work on plans to rein in bankruptcy and to provide liquidity for stabilizing the corporate financing market.

Broadly, there are two paths via which businesses are provided with funds. One is via banks, and the other is via the capital markets. The latter mostly happens in the corporate bonds and short-term financing markets. Among the two paths, the focus of this article is placed on liquidity trends in Korea’s short-term financing market as well as the risk factors. It also reviews the US Fed’s CP purchase program, and derives some implications for liquidity provision in Korea’s CP market.

CP and ESTB markets, a path of risk distribution

If the coronavirus pandemic dampens corporate sales and worsens financial conditions, the risk of bankruptcy will rise. In times of crisis, signs of bankruptcy usually emerge in the money market first, not in the corporate bond market where longer-term vehicles are traded. In Korea’s corporate bond market, bonds with 3- to 5-year maturities constitute a mainstream. On the other hand, money market instruments have a shorter maturity. For example, 90-day and 1-day debt instruments are primarily traded in the CP and ESTB markets, whereas 1-day instruments are the most common in the repo market where financial firms carry out secured transactions. In general, investors in longer-term corporate bonds are way more sensitive to any change in credit risk. This is because a change in a situation that looks trivial now could possibly escalate into an unexpected crisis. Hence, a corporate bond market elastically reflects changes in corporate credit risk. Any sign of a crisis in the market quickly leads liquidity to dry up.

Due to the short maturity, a firm can finance in the CP and ESTB markets even when it cannot raise capital in the corporate bond market. That is to say that, even if a firm cannot borrow for five years, it still can access to a 90-day instrument. In other words, a firm with a downgraded corporate rating will not be able to issue corporate debt, but still can try to survive by turning to short-term financing in the CP and ESTB markets. Hence, a bankruptcy tends to arrive at the CP and ESTB markets first before the resultant crisis rapidly spreads to the corporate bond market. This is one of the common features observed in many previous financial crises and economic crises. Given the nature of the CP and ESTB markets, it’s worth carefully monitoring the changes in prices and capital flows in those markets at a time of crisis. Especially when there is a rapid rise in price or liquidity indicators, policy authorities should concentrate its liquidity provision in the CP and ESTB markets, on top of the corporate bond market.

Assessing risk factors inherent in CP and ESTB

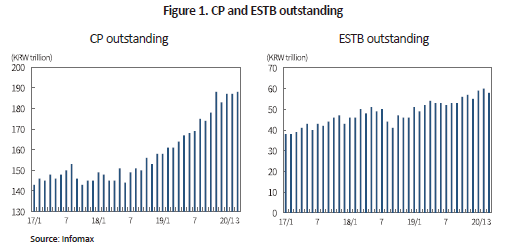

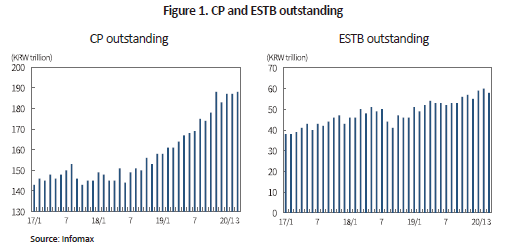

As of end-March, Korea’s CP and ESTB markets stood at KRW 246 trillion in terms of the outstanding amount. The markets can break into CP (KRW 188 trillion) and ESTB (KRW 58 trillion) segments. The CP segment consists of regular CP and asset-backed CP (ABCP) that is issued for asset securitization. Regular CP outstanding stood at KRW 64trillion while ABCP outstanding recorded KRW 124 trillion. In terms of the outstanding amount, maturities of 30–89 days account for the highest share in CP and ESTB, whereas ABCP with 180 days to 1-year maturities takes up the highest percentage. This suggests that most CP and ESTB mature in three month, while most ABCP issues have a six-month or longer maturity. The outstanding amount alone cannot sufficiently evidence a deepening liquidity shortage in the CP and ETB markets. Overall, CP outstanding at the end of each month stood at KRW 187 trillion, KRW 187 trillion, and KRW 188 trillion in January, February, and March 2020, respectively. During the same period, ESTB outstanding reached KRW 59 trillion, KRW 60 trillion, and KRW 58 trillion, respectively.

What’s concerning the most in the above data is the issuer composition. An absolutely large portion of CP and ESTB is issued by financial and insurance firms. The two subsectors combined account for 63.5% in regular CP outstanding and 59.3% in regular ABCP outstanding. This means that the financial sector will bear the biggest brunt of a potential liquidity crunch in the CP and ESTB markets.

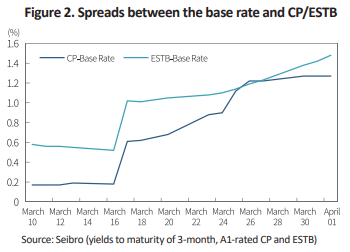

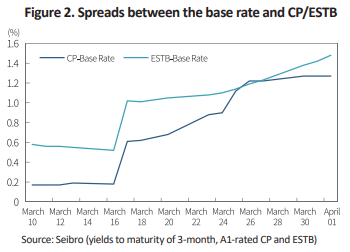

Prices, rather than the outstanding amount, are a better indicator of a liquidity shortage in those markets. The yields to maturity of A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB had remained stable before the Bank of Korea cut the interest rate from 1.25% to 0.75% on March 16, 2020. Since then, the spreads between CP and the base rate, and between the ESTB and the base rate have been widening abruptly. In general, an adjustment in the Bank of Korea’s base rate leads to a change in CP and ESTB yields in the money market. However, this wasn’t the case this time. A rate cut as drastic as 0.5 percentage points on March 16 didn’t trigger a meaningful change in yields in the CP and ESTB markets. CP and ESTB, both a typical money market instrument, tend to be sensitive to any change in the base rate. By contrast, the yields in the markets moved in the direction opposite to the base rate since March 23. This implies increasing concerns about credit risk in the CP and ESTB markets. As of April 1, 2020, the yields on A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB were 127bp and 148bp higher than the base rate, which seem high enough to raise concerns over short-term corporate financing.

The Fed’s CP purchase program

The rapid spread of the coronavirus caused into an abrupt liquidity shortage in the US financial market just as was the case with Korea. To tackle the fallout of Covid-19, the US Fed cut its key interest rate to the 0% range. When signs of a liquidity crunch emerged in the CP market, the Fed immediately unveiled its CP purchase program. On March 17, 2020, the Fed began its Commercial Paper Funding Facility 2020 (CPFF 2020) program aiming to provide liquidity to households and businesses. Under the program, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) is established to receive loans from the Fed, and to use the loans for purchasing 3-month CP (including asset-backed CP) that meets certain terms and conditions. The CP purchased by the SPV is offered as collaterals to the New York Fed, a credit provider. It is the US Treasury Department, not the New York Fed, that provides credit protection worth of $10 billion to the CPFF program via the Exchange Stabilization Fund. The CP eligible for the program should be rated at least A-1/P-1/F-1.

In addition, there is a limit on the maximum amount of CP the SPV can purchase. It is not allowed for the SPV to purchase an amount greater than the amount a single issuer had outstanding on a day between March 16, 2019 and March 16, 2020. The limit also includes the issuer’s CP outstanding purchased by all investors including the SPV. The price of CP is set at the 3-month overnight index swap rate plus 200bp. Also, each issuer registering to participate in the program should pay a 10bp fee of the maximum amount of its CP the SPV purchases. The SPV can purchase CP until March 16, 2021. If deemed necessary, the Fed can further extend the period. Even after March 16, 2021, the New York Fed will still provide liquidity to the SPV until the underlying assets held by the SPV mature.

The aforementioned terms and conditions of the CPFF 2020 demonstrate that the program is purposed to stabilize the market by liquidity provision. It’s worth mentioning that the program primarily targets an issuer with a temporary liquidity problem despite its higher credit rating. In other words, this is not to supply funds to marginal firms that had already been struggling even before the coronavirus epidemic. Not only does the program limit its target to issuers with a high rating, it also sets its purchase limit taking into account an issuer’s pre-coronavirus conditions. This could be interpreted as indicating how determined the government and the Fed are to address any financing shortage even viable firms could face amid a sudden liquidity crunch in the market.

Also notable is that the CPFF 2020 program is based on the Fed’s credit protection. Although the buyer of the CP is the Fed, it’s the federal government that takes the inherent risk. And such a dual structure seems to have a clear purpose of raising funds and stabilizing the market immediately. At a time of crisis, market liquidity quickly dries up. Without immediate funding, many firms could be faced with abrupt financing difficulties. Financing via the central bank with the power to issue currency is highly beneficial in comparison to financing from the private sector that is a nuisance and takes a long period of time. However, when a central bank purchases CP, it also takes on the credit risk of the private sector. This is why the US federal government steps in to provide credit protection to the CP. While the Fed immediately provides funds in a timely manner, the credit risk is borne by the federal government that has the power to collect tax, forming an effective cooperative structure between monetary and fiscal policies. Such an arrangement has critical implications for Korea that has a similar CP purchase program in operation.

Policy responses for money market stabilization

On March 24, Korea unveiled its financial market stabilization measures against the Covid-19 pandemic, including its CP and ESTB purchase program aiming to stabilize the corporate bond and short-term financial markets. Given the importance of CP and ESTB in corporate financing, such measures seem quite appropriate and effective. However, some details in management principles need adjusting to help the CP and ESTB purchase program to achieve intended policy effects.

More concretely, the program should be managed to help stabilize the yields and the overall CP and ESTB markets, rather than liquidity provision at individual firm levels. Yield stabilization is highly likely to help more debt to be issued. Towards that end, it’s advisable to limit the credit rating of eligible issuers, and set a per-issuer cap on the purchase. Given that corporate credit ratings are more likely to be downgraded amid the coronavirus epidemic, pre-coronavirus ratings should be used to choose eligible issuers for the program.

Also worth reviewing is a bold change in how to finance the program. Under the current measures, the purchase of CP and ESTB is expected to be financed by policy financing institutions such as the Korea Development Bank and the Industrial Bank of Korea. However, this has a problem because the only way those institutions finance the program is no different from issuing bonds in the market. In normal times, their bond issuance is less likely to trigger yield increases in the market. However, policy financing institutions’ bond issuance in times of crisis such as now could possibly push up the yields further due to the market’s low liquidity. Hence, it’s worth pondering upon the US case where the central bank, instead of policy financing institutions, uses its currency printing power for financing the program. The only problem is the transfer of credit risk to the central bank. Managing credit risk should fall under the area of fiscal policy, rather than central banking. To properly rein in the credit risk, the government may need to take a supplementary action under which it raises funds to be used for credit protection against CP and ESTB the central bank purchases. Once formed, such a cooperative structure between the central bank and the government would have an immense implication for any crisis to come in the future.

For market stabilization, it is also critical to make further efforts to provide liquidity to securities firms that take on the largest role in issuing CP and ESTB. Securities firms tend to depend largely on financing in the capital markets, especially short-term financing that is highly cost efficient. High reliance on short-term financing could have a profit-enhancing effect in normal times, but could destabilize financial conditions in times of crisis. Furthermore, the larger portion of debt guarantees related to real estate project finance is imposing an additional burden on liquidity risk management. In the long-run, those firms should channel more efforts into striking an equilibrium between short-term and long-term financing. For now, however, it’s worth considering liquidity provision to securities firms under the condition that they meet certain credit rating criteria and pay an additional interest rate. More concretely, it would be possible to provide short-term liquidity via securities organizations, or to make CP, ABCP, and ESTB issued by securities firms eligible for the program.

1) This refers to a risk arising from an unexpected event that imposes a negative shock on the overall economy or a specific industry. Examples include a natural disaster, a geopolitical risk, an industrial accident, or an epidemic.

As such, Covid-19, already in the pandemic level, is expected to impose a devastating impact on the global economy. Already, negative first-quarter growth in major developed economies is a consensus, and their second-quarter growth is forecast to be worse. On top of that, experts are putting off their estimated timing of the end of the pandemic as well as an economic rebound. Under the circumstances, all economic capabilities should be concentrated in preventing bankruptcy and therefore minimizing economic shocks. Bankruptcy usually causes massive layoffs, thereby diminishing consumption and triggering a chain reaction on relevant industries and firms. This could evolve into a more serious crisis. Hence, the government should quickly work on plans to rein in bankruptcy and to provide liquidity for stabilizing the corporate financing market.

Broadly, there are two paths via which businesses are provided with funds. One is via banks, and the other is via the capital markets. The latter mostly happens in the corporate bonds and short-term financing markets. Among the two paths, the focus of this article is placed on liquidity trends in Korea’s short-term financing market as well as the risk factors. It also reviews the US Fed’s CP purchase program, and derives some implications for liquidity provision in Korea’s CP market.

CP and ESTB markets, a path of risk distribution

If the coronavirus pandemic dampens corporate sales and worsens financial conditions, the risk of bankruptcy will rise. In times of crisis, signs of bankruptcy usually emerge in the money market first, not in the corporate bond market where longer-term vehicles are traded. In Korea’s corporate bond market, bonds with 3- to 5-year maturities constitute a mainstream. On the other hand, money market instruments have a shorter maturity. For example, 90-day and 1-day debt instruments are primarily traded in the CP and ESTB markets, whereas 1-day instruments are the most common in the repo market where financial firms carry out secured transactions. In general, investors in longer-term corporate bonds are way more sensitive to any change in credit risk. This is because a change in a situation that looks trivial now could possibly escalate into an unexpected crisis. Hence, a corporate bond market elastically reflects changes in corporate credit risk. Any sign of a crisis in the market quickly leads liquidity to dry up.

Due to the short maturity, a firm can finance in the CP and ESTB markets even when it cannot raise capital in the corporate bond market. That is to say that, even if a firm cannot borrow for five years, it still can access to a 90-day instrument. In other words, a firm with a downgraded corporate rating will not be able to issue corporate debt, but still can try to survive by turning to short-term financing in the CP and ESTB markets. Hence, a bankruptcy tends to arrive at the CP and ESTB markets first before the resultant crisis rapidly spreads to the corporate bond market. This is one of the common features observed in many previous financial crises and economic crises. Given the nature of the CP and ESTB markets, it’s worth carefully monitoring the changes in prices and capital flows in those markets at a time of crisis. Especially when there is a rapid rise in price or liquidity indicators, policy authorities should concentrate its liquidity provision in the CP and ESTB markets, on top of the corporate bond market.

Assessing risk factors inherent in CP and ESTB

As of end-March, Korea’s CP and ESTB markets stood at KRW 246 trillion in terms of the outstanding amount. The markets can break into CP (KRW 188 trillion) and ESTB (KRW 58 trillion) segments. The CP segment consists of regular CP and asset-backed CP (ABCP) that is issued for asset securitization. Regular CP outstanding stood at KRW 64trillion while ABCP outstanding recorded KRW 124 trillion. In terms of the outstanding amount, maturities of 30–89 days account for the highest share in CP and ESTB, whereas ABCP with 180 days to 1-year maturities takes up the highest percentage. This suggests that most CP and ESTB mature in three month, while most ABCP issues have a six-month or longer maturity. The outstanding amount alone cannot sufficiently evidence a deepening liquidity shortage in the CP and ETB markets. Overall, CP outstanding at the end of each month stood at KRW 187 trillion, KRW 187 trillion, and KRW 188 trillion in January, February, and March 2020, respectively. During the same period, ESTB outstanding reached KRW 59 trillion, KRW 60 trillion, and KRW 58 trillion, respectively.

What’s concerning the most in the above data is the issuer composition. An absolutely large portion of CP and ESTB is issued by financial and insurance firms. The two subsectors combined account for 63.5% in regular CP outstanding and 59.3% in regular ABCP outstanding. This means that the financial sector will bear the biggest brunt of a potential liquidity crunch in the CP and ESTB markets.

Prices, rather than the outstanding amount, are a better indicator of a liquidity shortage in those markets. The yields to maturity of A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB had remained stable before the Bank of Korea cut the interest rate from 1.25% to 0.75% on March 16, 2020. Since then, the spreads between CP and the base rate, and between the ESTB and the base rate have been widening abruptly. In general, an adjustment in the Bank of Korea’s base rate leads to a change in CP and ESTB yields in the money market. However, this wasn’t the case this time. A rate cut as drastic as 0.5 percentage points on March 16 didn’t trigger a meaningful change in yields in the CP and ESTB markets. CP and ESTB, both a typical money market instrument, tend to be sensitive to any change in the base rate. By contrast, the yields in the markets moved in the direction opposite to the base rate since March 23. This implies increasing concerns about credit risk in the CP and ESTB markets. As of April 1, 2020, the yields on A1-rated 3-month CP and ESTB were 127bp and 148bp higher than the base rate, which seem high enough to raise concerns over short-term corporate financing.

The Fed’s CP purchase program

The rapid spread of the coronavirus caused into an abrupt liquidity shortage in the US financial market just as was the case with Korea. To tackle the fallout of Covid-19, the US Fed cut its key interest rate to the 0% range. When signs of a liquidity crunch emerged in the CP market, the Fed immediately unveiled its CP purchase program. On March 17, 2020, the Fed began its Commercial Paper Funding Facility 2020 (CPFF 2020) program aiming to provide liquidity to households and businesses. Under the program, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) is established to receive loans from the Fed, and to use the loans for purchasing 3-month CP (including asset-backed CP) that meets certain terms and conditions. The CP purchased by the SPV is offered as collaterals to the New York Fed, a credit provider. It is the US Treasury Department, not the New York Fed, that provides credit protection worth of $10 billion to the CPFF program via the Exchange Stabilization Fund. The CP eligible for the program should be rated at least A-1/P-1/F-1.

In addition, there is a limit on the maximum amount of CP the SPV can purchase. It is not allowed for the SPV to purchase an amount greater than the amount a single issuer had outstanding on a day between March 16, 2019 and March 16, 2020. The limit also includes the issuer’s CP outstanding purchased by all investors including the SPV. The price of CP is set at the 3-month overnight index swap rate plus 200bp. Also, each issuer registering to participate in the program should pay a 10bp fee of the maximum amount of its CP the SPV purchases. The SPV can purchase CP until March 16, 2021. If deemed necessary, the Fed can further extend the period. Even after March 16, 2021, the New York Fed will still provide liquidity to the SPV until the underlying assets held by the SPV mature.

The aforementioned terms and conditions of the CPFF 2020 demonstrate that the program is purposed to stabilize the market by liquidity provision. It’s worth mentioning that the program primarily targets an issuer with a temporary liquidity problem despite its higher credit rating. In other words, this is not to supply funds to marginal firms that had already been struggling even before the coronavirus epidemic. Not only does the program limit its target to issuers with a high rating, it also sets its purchase limit taking into account an issuer’s pre-coronavirus conditions. This could be interpreted as indicating how determined the government and the Fed are to address any financing shortage even viable firms could face amid a sudden liquidity crunch in the market.

Also notable is that the CPFF 2020 program is based on the Fed’s credit protection. Although the buyer of the CP is the Fed, it’s the federal government that takes the inherent risk. And such a dual structure seems to have a clear purpose of raising funds and stabilizing the market immediately. At a time of crisis, market liquidity quickly dries up. Without immediate funding, many firms could be faced with abrupt financing difficulties. Financing via the central bank with the power to issue currency is highly beneficial in comparison to financing from the private sector that is a nuisance and takes a long period of time. However, when a central bank purchases CP, it also takes on the credit risk of the private sector. This is why the US federal government steps in to provide credit protection to the CP. While the Fed immediately provides funds in a timely manner, the credit risk is borne by the federal government that has the power to collect tax, forming an effective cooperative structure between monetary and fiscal policies. Such an arrangement has critical implications for Korea that has a similar CP purchase program in operation.

Policy responses for money market stabilization

On March 24, Korea unveiled its financial market stabilization measures against the Covid-19 pandemic, including its CP and ESTB purchase program aiming to stabilize the corporate bond and short-term financial markets. Given the importance of CP and ESTB in corporate financing, such measures seem quite appropriate and effective. However, some details in management principles need adjusting to help the CP and ESTB purchase program to achieve intended policy effects.

More concretely, the program should be managed to help stabilize the yields and the overall CP and ESTB markets, rather than liquidity provision at individual firm levels. Yield stabilization is highly likely to help more debt to be issued. Towards that end, it’s advisable to limit the credit rating of eligible issuers, and set a per-issuer cap on the purchase. Given that corporate credit ratings are more likely to be downgraded amid the coronavirus epidemic, pre-coronavirus ratings should be used to choose eligible issuers for the program.

Also worth reviewing is a bold change in how to finance the program. Under the current measures, the purchase of CP and ESTB is expected to be financed by policy financing institutions such as the Korea Development Bank and the Industrial Bank of Korea. However, this has a problem because the only way those institutions finance the program is no different from issuing bonds in the market. In normal times, their bond issuance is less likely to trigger yield increases in the market. However, policy financing institutions’ bond issuance in times of crisis such as now could possibly push up the yields further due to the market’s low liquidity. Hence, it’s worth pondering upon the US case where the central bank, instead of policy financing institutions, uses its currency printing power for financing the program. The only problem is the transfer of credit risk to the central bank. Managing credit risk should fall under the area of fiscal policy, rather than central banking. To properly rein in the credit risk, the government may need to take a supplementary action under which it raises funds to be used for credit protection against CP and ESTB the central bank purchases. Once formed, such a cooperative structure between the central bank and the government would have an immense implication for any crisis to come in the future.

For market stabilization, it is also critical to make further efforts to provide liquidity to securities firms that take on the largest role in issuing CP and ESTB. Securities firms tend to depend largely on financing in the capital markets, especially short-term financing that is highly cost efficient. High reliance on short-term financing could have a profit-enhancing effect in normal times, but could destabilize financial conditions in times of crisis. Furthermore, the larger portion of debt guarantees related to real estate project finance is imposing an additional burden on liquidity risk management. In the long-run, those firms should channel more efforts into striking an equilibrium between short-term and long-term financing. For now, however, it’s worth considering liquidity provision to securities firms under the condition that they meet certain credit rating criteria and pay an additional interest rate. More concretely, it would be possible to provide short-term liquidity via securities organizations, or to make CP, ABCP, and ESTB issued by securities firms eligible for the program.

1) This refers to a risk arising from an unexpected event that imposes a negative shock on the overall economy or a specific industry. Examples include a natural disaster, a geopolitical risk, an industrial accident, or an epidemic.