Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

A Thought on Share Repurchase Arrangements and the Effect of Enhancing Shareholder Value

Publication date Oct. 06, 2020

Summary

Share repurchases rose sharply in Korea as the cap on the amount of a share repurchase was temporarily relaxed due to the stock market fluctuations amid the Covid-19 crisis. In general, a firm’s decision to buy back its own shares for the purpose of stabilizing share prices and enhancing shareholder value is welcomed by investors. However, not all stock repurchases produce the same effect. If the repurchased shares are later sold again in an open market instead of being canceled, this could make the effect only temporary. Hence, investors should keep a close eye on what happens to the repurchased shares. In another case, disclosures that look exactly the same could result in totally different transactions under the current regulation, which requires extra caution. Unlike direct repurchases where a firm directly purchases treasury shares, indirect repurchases via trust are virtually unregulated: There are de facto no restriction in place on the acquisition period, the purchase volume, and disposal of the treasury shares even within the contract period. Such a regulatory structure is likely to lead to uncertainties around whether or not treasury shares are actually purchased, or when the repurchase actually occurs, etc. Also this could weaken the intended effect of price stabilization, which is different from investor expectations.

There are concerns that share buyback decisions during the recent market turmoil could be nothing more than a temporary measure for short-term capital gains, instead of pursuing long-term shareholder value. This calls for investors to better understand various share repurchase arrangements and to pay close attention to how and whether treasury shares are acquired, held, and sold. This will certainly help investors to better assess the effect of enhancing shareholder value. Also necessary is continuous discussion about how to improve the relevant regulation and disclosure rules for share repurchases to produce their intended effects.

There are concerns that share buyback decisions during the recent market turmoil could be nothing more than a temporary measure for short-term capital gains, instead of pursuing long-term shareholder value. This calls for investors to better understand various share repurchase arrangements and to pay close attention to how and whether treasury shares are acquired, held, and sold. This will certainly help investors to better assess the effect of enhancing shareholder value. Also necessary is continuous discussion about how to improve the relevant regulation and disclosure rules for share repurchases to produce their intended effects.

More recently, more and more firms have been buying back their own shares as the cap on share repurchases (or called buybacks) was relaxed as part of market stabilization measures that originally intended to curb abrupt stock price swings amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Investors tend to welcome a company’s buyback decision because they usually expect a buyback to reduce the number of floating stock and thus directly prevent share prices from falling. Also, they consider it a sign of the stock’s undervaluation and a determined management action to enhance shareholder value. However, not all stock buybacks produce the same effect. Although buybacks are known for the effect of boosting stock prices, the meaning and impact of those on shareholder value could vary depending on the nature. Hence, it’s inappropriate to treat all stock buybacks in the same way. Investors need to closely keep track of what a firm does with the repurchased shares, and every detail on actual transactions. With regard to this issue, this article tries to explore what investors should consider in properly understanding a stock buyback and assessing its impact on shareholder value. In the end, it touches upon better ways to disseminate relevant information to help investors make informed decisions.

Disposal of repurchased shares and limited shareholder returns

In general, a firm’s disclosure about a stock buyback pushes up its share prices primarily via two paths. First, a stock buyback imposes a direct impact on the supply and demand of the firm’s floating shares. The shares once purchased by the firm are no longer available for trading, which naturally reduces the supply and raises the stock value. Also notable is that the shares repurchased become treasury shares that have no rights to demand dividends or new shares. This could offer shareholders higher dividends or a larger number of stocks when there’s a secondary offering or bonus issue in the future. Second, a stock buyback is viewed as positive news among shareholders, which could induce more investors to buy the shares. When a firm announces a buyback plan to buy more treasury shares with an aim to stabilize share prices and improve shareholder value, it usually appeals to investors. A share buyback is usually read as indirect evidence that insiders consider the shares undervalued. This is also regarded as a proof that the firm has sufficient cash to buy back its own shares. Against the backdrop, a firm’s share prices usually rise after its disclosure of a share buyback. This also pushes up the value of shareholder assets, and helps investors to favor a firm’s decision to repurchase the shares.

However, it’s important to note that the shares repurchased are not canceled forever. If a firm decides not to cancel them but to hold them for selling them later in an open market, this could again push up the number of floating shares. In this case, the effect of a stock buyback is limited at best. In other words, shareholders’ expectations for the long-lasting effect on shareholder value would be only possible as long as the repurchased shares are canceled to cut the number of outstanding shares permanently.

Hence, investors who try to assess the effect of a share repurchase disclosure need to carefully look into what happens to the repurchased shares. The magnitude and duration of the effect of shareholder returns could vary depending on whether the firm cancels, keeps holding, or disposes of the treasury shares. Because most stock repurchases do not lead to share cancelation in Korea’s stock market, investors need to take an extra caution. It’s possible for any firm to wrongfully use a stock buyback for buying at low and selling at high for capital gains. Indeed, most of the stock buyback programs disclosed in Korea state that their purpose is to improve shareholder value. However, if they repeatedly purchase and sell treasury shares, that would only bring the stock prices up and down to quite an extent and mislead investors, which has nothing to do with shareholder returns in any sense.

Impact of share buyback regulation on shareholder returns1)

When investors evaluate a firm’s stock buyback from the perspective of shareholder value, it’s worth looking into the process via which the firm repurchases its own stocks, on top of what the firm does with those shares. In general, investors tend to believe that a share repurchase program is implemented immediately and fully in the same manner as the original disclosure. By contrast to such a belief, it often takes long for the firm to buy back the shares, and sometimes the buyback volume is much smaller than what the disclosure stated. Or, the entire volume of shares repurchased is often sold again.

Before looking into why this happens, it’s worth exploring how a firm purchases treasury shares under the current regulation. There are roughly three paths. The first and the simplest path to a share buyback would be for a firm to disclose the number of shares for its buyback and to directly purchase them on the exchange or in the OTC market (Article 341 (1) 1, Commercial Act). Or, a firm may enter into a contract with a trustee (a bank or a trust company) to entrust an amount of money to the trustee which buys back shares on behalf of the firm (Article 165-3 (4), Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act). The second path is that, if the contract is terminated or expired, the treasury stocks held by the trustee can be returned to the firm (Article 165-3 (1) 2, FSCMA). The first and second paths are called direct repurchase where the firm directly owns its treasury stocks. On the contrary, the third path, an indirect repurchase, is a trustee financial firm acquiring treasury stocks during the contract period. Each path is different as follows.

First, a share repurchase via the second path usually takes longer than a direct repurchase using the first path. The current regulation obligates a firm opting for the first path to complete all purchases within three months after the day of disclosure (Article 176 (2) 3, Enforcement Decree of the FSCMA; Article 5 (9) 1, Regulations on Issuance, Public Disclosure, etc. of Securities).2) However, a trust contract usually has a 6-month or longer period (Article 176-2 (2) 6, Enforcement Decree of the FSCMA), which can be extended further upon request from the trustor firm. This means it often takes several years before termination. That is to say that there might be years of time before the firm actually acquires treasury shares under a trust contract.

Second, once a firm opting for a direct repurchase via the first and second paths discloses the number shares it plans to buy back, the firm is mandated to buy all of them. Otherwise, it is subject to a legal sanction. However, no restriction is applied to indirect repurchases via the third path. This means a looming possibility where a firm actually doesn’t buy back all the shares as promised in the disclosure statement.

Third, a firm opting for direct repurchases can only purchase treasury shares during the disclosed period, while indirect repurchases allow the trustee to either purchase or sell treasury shares. So in an extreme example, a firm enters into a trust contract via which to purchase its own shares to sell them again and again for capital gains during the contract period, which is perfectly legal.3)

Fourth, a trustor firm can take back the shares held by the trustee, or receive cash. When the firm demands a cash return, there is no repurchase of actual shares although such a transaction is disclosed as “a trust contract established for a share repurchase”.

If a firm discloses a share buyback for directly acquiring shares in the market, it should buy all of the shares stated in the disclosure within three months starting from the day of disclosure. However, indirect repurchases de facto place no limit to the repurchase period or the purchase amount. Also, it is allowed to sell the repurchased shares within the contract period. Despite such flexibility, the current regulation views share repurchases via trust contract as a tool for enhancing shareholder value for some reasons. From investors’ perspective, a trust contract is interpreted as a firm’s willingness to boost share prices. They expect the trustee to use its capital to buy more treasury shares during a market downturn, which, they hope, could effectively defend an abrupt price fall. However, the existing literature on acquiring treasury shares has centered around only repurchase disclosures, which lack empirical evidence on whether an indirect repurchase is actually effective to prevent a stock price decline. No matter it’s effective or not, it cannot prevent the repurchased shares from being sold again when the price goes up, which hardly guarantees the price stabilization effect expected by investors. In sum, the different nature between direct repurchases or repurchases via trust leads to one possibility: Share repurchases via trust in comparison with direct repurchases are not only uncertain in terms of whether or not the firm actually acquires treasury shares, but also ineffective in enhancing shareholder returns.

Caution required for disclosure on actual treasury stock transactions

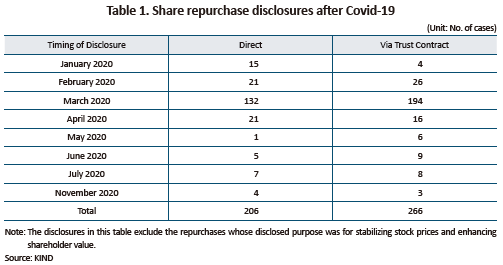

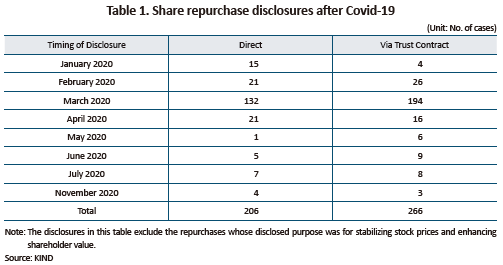

Since the Covid-19 outbreak, share buybacks have been on the rapid increase. Between January 1 and August 11, 2020, there were a total of 572 share repurchase disclosures, of which 206 were direct repurchases with 266 via trust contract. More than a half of stock repurchases (326 disclosures) were concentrated in March when the stock prices plunged and the daily cap on a stock repurchase was relaxed.

It’s uneasy to figure out from the data how many of those shares disclosed during the stock price plunge in March 2020 are to be actually repurchased, or how long firms will keep holding those shares. One useful albeit limited measure could be disclosures about share cancelation, which reveals some disturbing facts about shareholder returns. Of a total of 206 disclosures on direct repurchases, only 17 disclosures said they would cancel the repurchased shares. In other words, most of the share repurchases are subject to high levels of uncertainty about whether or not they are to be repurchased, and whether the repurchased shares are held as treasury shares or sold.

Korea’s current share repurchase regulation bars firms from selling them for six months after the day of final repurchase, making it less likely for the shares repurchased intensively during March and April to be sold to the market immediately. This also holds true for repurchases via trust contract. The current regulation bans any trust contract from being terminated within 6-month, making 6-month the minimum period of a trust contract. This means that most share repurchases in this analysis are still under contract. In other words, if the shares were repurchased intensively during the Covid-19-triggered turmoil and there was no subsequent repurchase or new trust contract, those shares should be sold only after six months, which will be roughly the end of 2020. With the share prices being above a certain level, the firms may try to sell the repurchased shares for capital gains.

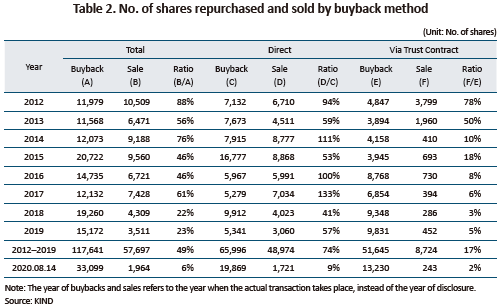

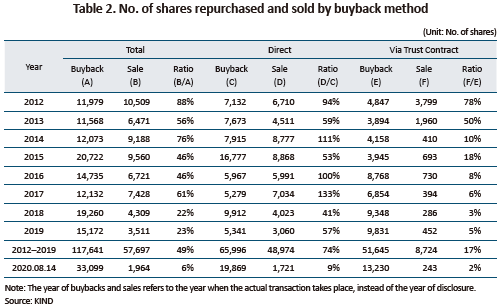

Table 2 demonstrates the number of treasury shares purchased and sold each year since 2012, by measure of when actual trading takes place. This could provide useful data for estimating the ballpark figure of the net purchase of treasury shares. Between 2012 and 2019, listed companies purchased 118,000 treasury shares and sold 58,000 shares among them. This means a half of share repurchases were sold again. Up to August 14, 2020, the number of repurchased shares stood at 33,000, of which only 2,000 shares were sold. Because this is far lower than the average disposal rate than the past, it’s highly probable that the firms will sell more treasury shares in the future even under the assumption that the net purchase rate of the past remains intact.

The column F in Table 2 indicates disposals under trust contracts, which include both the sales for the sake of managing trust assets during the contract period, and the sales for returning cash to the trustor upon contract expiration. In the early 2010s, more than a half of treasury shares purchased via trust contract were sold again, which hardly seems like a meaningful acquisition. However, the ratio of sold shares to purchased ones began abruptly falling in 2016 to reach as low as 5.3% in 2019 on a cumulative basis.

The overall average looks fine because only a fraction of treasury shares purchased via trust contract were sold. Still, however, this requires extra caution for ordinary investors trading individual stocks. As mentioned earlier, there are some extreme cases where only a small part of treasury shares were actually acquired.

For example, firm A entered into a trust contract in March 2020 for buying back its own shares worth of a KRW 3 billion for one year. After three months later, it disclosed in May that under the contract it repurchased a total of 597,000 shares at KRW 2.99 billion. Since then, however, no further disclosure has been made with regard to who owns those shares. A more recent transaction history shows that starting from June—a month after the May disclosure—the firm continuously sold the repurchased shares. Up to August, it sold 429,000 shares or 72% of its repurchased shares, which leaves only 168,000 shares in hand. Because the trust contract is still effective, it’s possible for the remaining shares to be sold as well.

In another case, firm B entered into a trust contract during the market plunge triggered by Covid-19, and indirectly repurchased its own shares during the early days of the contract. However, all of those shares were already sold. It was March 20, 2020 when firm B first established a trust contract via which to acquire treasury shares worth of KRW 2 billion. One month later, it accordingly purchased via trust contract 807,000 treasury shares (KRW 0.97 billion), all of which were sold at the end of May. Thanks to the upbeat mood in the stock market during the three-month period, the sales amount went up to KRW 2.6 billion. Thanks to that transaction, firm B earned capital gains of KRW 1.6 billion, marking a 2-month return of 160%.

Again, the size of share repurchases as of mid-August 2020 largely dwarfed that of sales compared with the past. As the stock market is on the rise after quickly recovering from the March plunge, firms have no reason to actively sell treasury shares in their hands. Because the current regulation bans treasury shares bought directly by firms or indirectly via trust contract from being sold within six months after acquisition, the treasury shares acquired intensively during this March and April cannot be sold yet. Investors should be aware of a possible increase in sales of treasury shares when the sales becomes available later.

Another area of concern lies in disclosure: It’s not easy to figure out the current state of treasury shares indirectly purchased via trust contract. When a firm directly repurchases its own shares, it is mandated to release a “share repurchase report” after the acquisition is completed. The report discloses the number of ordered shares, the number of purchased shares, the purchase price, whether or not their repurchase plan complies with actual transactions, and the firm’s holdings of treasury shares. Because the regulation requires a firm directly purchasing treasury shares to complete the planned transaction within three months after the disclosure, it’s possible for investors to figure out the progress of actual transactions. However, this is not the case for indirect repurchases via trust contract. The regulation also mandates reporting of transaction history via a “share repurchase via trust contract report” within three months after establishing a trust contract.

However, the different is that indirect repurchases via trust contract are free from the three-month limit. Because the contract period can be extended further, the transaction period can lengthen further as well. Hence, the report that is supposed to be submitted within three months cannot effectively reflect all transactions. If a firm indirectly purchases or sells treasury shares via trust contract more than three months after the disclosure, such transactions are not disclosed at all, which makes it all the more difficult to figure out what actually happened. A desirable fix to this issue would be a tougher disclosure requirement that obligates firms to report their purchase or sale of treasury shares during the whole period of trust contract.4)

Conclusion and implications

The Covid-19 pandemic helped double the number of firms repurchasing their own shares, and the increase was concentrated in March 2020. As many firms made every effort to prevent their share prices from declining, this could have imposed a direct or indirect impact on stabilizing share prices during the stock market turmoil in March. However, it’s also possible for the share buyback decision during the turmoil to do nothing more than a temporary measure for earning short-term capital gains. In other words, instead of canceling the repurchased shares, firms may sell those to the market again. Judging from the current share repurchase regulation, there’s a high possibility that the size of repurchases disclosed as part of a trust contract could be different from that of actual acquisition, which requires caution for investors.

All of those conditions call for investors to deepen their understanding about the differences in share repurchase arrangements between direct and indirect repurchases, or between a firm directly repurchasing shares and indirectly repurchasing them via trust contract. If those shares are sold again, instead of being canceled, it’s hard to expect a long-term enhancement in shareholder value. Short-term investors may enjoy temporary profits from disclosures on share repurchase, or the subsequent fall in the number of floating shares. However, this could hardly provide higher returns to longer-term shareholders. Because a trust contract gives a trustor firm too much discretion and excessively diverse decision-making opportunities, there’s always a possibility that the actual repurchase falls short of investor expectations. The hard-to-predict nature of this issue requires continuous attention and a cautious approach.

Also necessary in this area is further discussion about how to improve share repurchase regulation and disclosure systems. More regulatory effort should be made to improve investors’ predictability about share repurchase programs and to prevent firms from making irresponsible decisions. Last but not least, improvements in disclosure requirements will help investors to gain more information in a timely manner for making informed investment decisions.

1) Kim, Y.H. & Jung, S.C., 2008, Determinants of stock repurchase methods and the test of opportunistic behavior hypothesis, Korea Business Review 37(5), 1205-1232.

Korea Listed Companies Association, 2020, Practice guidelines on listed companies’ purchase, disposal, and cancelation of treasury stocks, KLCA 2020-10.

2) When the shares are returned under the trust contract, the firm’s actual repurchase occurs after the termination of expiration of the contract. Hence, the three-month period begins with a disclosure of the contract’s expiration or termination.

3) When a trustee sells (purchases) the treasury shares it purchased (sold) during the contract period, there should be at least a onemonth time span between the purchase and disposal.

4) Although firms do not disclose their actual repurchase transactions, it doesn’t mean the relevant information is non-public. It’s possible to check the acquisition or sale of treasury shares in the history of individual transactions provided by KIND. However, the transaction history only provides the date of transactions and the number of shares traded without the date of disclosure. The only way to figure out how each disclosure was implemented is to manually compare each disclosure with respective transaction history.

Disposal of repurchased shares and limited shareholder returns

In general, a firm’s disclosure about a stock buyback pushes up its share prices primarily via two paths. First, a stock buyback imposes a direct impact on the supply and demand of the firm’s floating shares. The shares once purchased by the firm are no longer available for trading, which naturally reduces the supply and raises the stock value. Also notable is that the shares repurchased become treasury shares that have no rights to demand dividends or new shares. This could offer shareholders higher dividends or a larger number of stocks when there’s a secondary offering or bonus issue in the future. Second, a stock buyback is viewed as positive news among shareholders, which could induce more investors to buy the shares. When a firm announces a buyback plan to buy more treasury shares with an aim to stabilize share prices and improve shareholder value, it usually appeals to investors. A share buyback is usually read as indirect evidence that insiders consider the shares undervalued. This is also regarded as a proof that the firm has sufficient cash to buy back its own shares. Against the backdrop, a firm’s share prices usually rise after its disclosure of a share buyback. This also pushes up the value of shareholder assets, and helps investors to favor a firm’s decision to repurchase the shares.

However, it’s important to note that the shares repurchased are not canceled forever. If a firm decides not to cancel them but to hold them for selling them later in an open market, this could again push up the number of floating shares. In this case, the effect of a stock buyback is limited at best. In other words, shareholders’ expectations for the long-lasting effect on shareholder value would be only possible as long as the repurchased shares are canceled to cut the number of outstanding shares permanently.

Hence, investors who try to assess the effect of a share repurchase disclosure need to carefully look into what happens to the repurchased shares. The magnitude and duration of the effect of shareholder returns could vary depending on whether the firm cancels, keeps holding, or disposes of the treasury shares. Because most stock repurchases do not lead to share cancelation in Korea’s stock market, investors need to take an extra caution. It’s possible for any firm to wrongfully use a stock buyback for buying at low and selling at high for capital gains. Indeed, most of the stock buyback programs disclosed in Korea state that their purpose is to improve shareholder value. However, if they repeatedly purchase and sell treasury shares, that would only bring the stock prices up and down to quite an extent and mislead investors, which has nothing to do with shareholder returns in any sense.

Impact of share buyback regulation on shareholder returns1)

When investors evaluate a firm’s stock buyback from the perspective of shareholder value, it’s worth looking into the process via which the firm repurchases its own stocks, on top of what the firm does with those shares. In general, investors tend to believe that a share repurchase program is implemented immediately and fully in the same manner as the original disclosure. By contrast to such a belief, it often takes long for the firm to buy back the shares, and sometimes the buyback volume is much smaller than what the disclosure stated. Or, the entire volume of shares repurchased is often sold again.

Before looking into why this happens, it’s worth exploring how a firm purchases treasury shares under the current regulation. There are roughly three paths. The first and the simplest path to a share buyback would be for a firm to disclose the number of shares for its buyback and to directly purchase them on the exchange or in the OTC market (Article 341 (1) 1, Commercial Act). Or, a firm may enter into a contract with a trustee (a bank or a trust company) to entrust an amount of money to the trustee which buys back shares on behalf of the firm (Article 165-3 (4), Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act). The second path is that, if the contract is terminated or expired, the treasury stocks held by the trustee can be returned to the firm (Article 165-3 (1) 2, FSCMA). The first and second paths are called direct repurchase where the firm directly owns its treasury stocks. On the contrary, the third path, an indirect repurchase, is a trustee financial firm acquiring treasury stocks during the contract period. Each path is different as follows.

First, a share repurchase via the second path usually takes longer than a direct repurchase using the first path. The current regulation obligates a firm opting for the first path to complete all purchases within three months after the day of disclosure (Article 176 (2) 3, Enforcement Decree of the FSCMA; Article 5 (9) 1, Regulations on Issuance, Public Disclosure, etc. of Securities).2) However, a trust contract usually has a 6-month or longer period (Article 176-2 (2) 6, Enforcement Decree of the FSCMA), which can be extended further upon request from the trustor firm. This means it often takes several years before termination. That is to say that there might be years of time before the firm actually acquires treasury shares under a trust contract.

Second, once a firm opting for a direct repurchase via the first and second paths discloses the number shares it plans to buy back, the firm is mandated to buy all of them. Otherwise, it is subject to a legal sanction. However, no restriction is applied to indirect repurchases via the third path. This means a looming possibility where a firm actually doesn’t buy back all the shares as promised in the disclosure statement.

Third, a firm opting for direct repurchases can only purchase treasury shares during the disclosed period, while indirect repurchases allow the trustee to either purchase or sell treasury shares. So in an extreme example, a firm enters into a trust contract via which to purchase its own shares to sell them again and again for capital gains during the contract period, which is perfectly legal.3)

Fourth, a trustor firm can take back the shares held by the trustee, or receive cash. When the firm demands a cash return, there is no repurchase of actual shares although such a transaction is disclosed as “a trust contract established for a share repurchase”.

If a firm discloses a share buyback for directly acquiring shares in the market, it should buy all of the shares stated in the disclosure within three months starting from the day of disclosure. However, indirect repurchases de facto place no limit to the repurchase period or the purchase amount. Also, it is allowed to sell the repurchased shares within the contract period. Despite such flexibility, the current regulation views share repurchases via trust contract as a tool for enhancing shareholder value for some reasons. From investors’ perspective, a trust contract is interpreted as a firm’s willingness to boost share prices. They expect the trustee to use its capital to buy more treasury shares during a market downturn, which, they hope, could effectively defend an abrupt price fall. However, the existing literature on acquiring treasury shares has centered around only repurchase disclosures, which lack empirical evidence on whether an indirect repurchase is actually effective to prevent a stock price decline. No matter it’s effective or not, it cannot prevent the repurchased shares from being sold again when the price goes up, which hardly guarantees the price stabilization effect expected by investors. In sum, the different nature between direct repurchases or repurchases via trust leads to one possibility: Share repurchases via trust in comparison with direct repurchases are not only uncertain in terms of whether or not the firm actually acquires treasury shares, but also ineffective in enhancing shareholder returns.

Caution required for disclosure on actual treasury stock transactions

Since the Covid-19 outbreak, share buybacks have been on the rapid increase. Between January 1 and August 11, 2020, there were a total of 572 share repurchase disclosures, of which 206 were direct repurchases with 266 via trust contract. More than a half of stock repurchases (326 disclosures) were concentrated in March when the stock prices plunged and the daily cap on a stock repurchase was relaxed.

Korea’s current share repurchase regulation bars firms from selling them for six months after the day of final repurchase, making it less likely for the shares repurchased intensively during March and April to be sold to the market immediately. This also holds true for repurchases via trust contract. The current regulation bans any trust contract from being terminated within 6-month, making 6-month the minimum period of a trust contract. This means that most share repurchases in this analysis are still under contract. In other words, if the shares were repurchased intensively during the Covid-19-triggered turmoil and there was no subsequent repurchase or new trust contract, those shares should be sold only after six months, which will be roughly the end of 2020. With the share prices being above a certain level, the firms may try to sell the repurchased shares for capital gains.

Table 2 demonstrates the number of treasury shares purchased and sold each year since 2012, by measure of when actual trading takes place. This could provide useful data for estimating the ballpark figure of the net purchase of treasury shares. Between 2012 and 2019, listed companies purchased 118,000 treasury shares and sold 58,000 shares among them. This means a half of share repurchases were sold again. Up to August 14, 2020, the number of repurchased shares stood at 33,000, of which only 2,000 shares were sold. Because this is far lower than the average disposal rate than the past, it’s highly probable that the firms will sell more treasury shares in the future even under the assumption that the net purchase rate of the past remains intact.

The overall average looks fine because only a fraction of treasury shares purchased via trust contract were sold. Still, however, this requires extra caution for ordinary investors trading individual stocks. As mentioned earlier, there are some extreme cases where only a small part of treasury shares were actually acquired.

For example, firm A entered into a trust contract in March 2020 for buying back its own shares worth of a KRW 3 billion for one year. After three months later, it disclosed in May that under the contract it repurchased a total of 597,000 shares at KRW 2.99 billion. Since then, however, no further disclosure has been made with regard to who owns those shares. A more recent transaction history shows that starting from June—a month after the May disclosure—the firm continuously sold the repurchased shares. Up to August, it sold 429,000 shares or 72% of its repurchased shares, which leaves only 168,000 shares in hand. Because the trust contract is still effective, it’s possible for the remaining shares to be sold as well.

In another case, firm B entered into a trust contract during the market plunge triggered by Covid-19, and indirectly repurchased its own shares during the early days of the contract. However, all of those shares were already sold. It was March 20, 2020 when firm B first established a trust contract via which to acquire treasury shares worth of KRW 2 billion. One month later, it accordingly purchased via trust contract 807,000 treasury shares (KRW 0.97 billion), all of which were sold at the end of May. Thanks to the upbeat mood in the stock market during the three-month period, the sales amount went up to KRW 2.6 billion. Thanks to that transaction, firm B earned capital gains of KRW 1.6 billion, marking a 2-month return of 160%.

Again, the size of share repurchases as of mid-August 2020 largely dwarfed that of sales compared with the past. As the stock market is on the rise after quickly recovering from the March plunge, firms have no reason to actively sell treasury shares in their hands. Because the current regulation bans treasury shares bought directly by firms or indirectly via trust contract from being sold within six months after acquisition, the treasury shares acquired intensively during this March and April cannot be sold yet. Investors should be aware of a possible increase in sales of treasury shares when the sales becomes available later.

Another area of concern lies in disclosure: It’s not easy to figure out the current state of treasury shares indirectly purchased via trust contract. When a firm directly repurchases its own shares, it is mandated to release a “share repurchase report” after the acquisition is completed. The report discloses the number of ordered shares, the number of purchased shares, the purchase price, whether or not their repurchase plan complies with actual transactions, and the firm’s holdings of treasury shares. Because the regulation requires a firm directly purchasing treasury shares to complete the planned transaction within three months after the disclosure, it’s possible for investors to figure out the progress of actual transactions. However, this is not the case for indirect repurchases via trust contract. The regulation also mandates reporting of transaction history via a “share repurchase via trust contract report” within three months after establishing a trust contract.

However, the different is that indirect repurchases via trust contract are free from the three-month limit. Because the contract period can be extended further, the transaction period can lengthen further as well. Hence, the report that is supposed to be submitted within three months cannot effectively reflect all transactions. If a firm indirectly purchases or sells treasury shares via trust contract more than three months after the disclosure, such transactions are not disclosed at all, which makes it all the more difficult to figure out what actually happened. A desirable fix to this issue would be a tougher disclosure requirement that obligates firms to report their purchase or sale of treasury shares during the whole period of trust contract.4)

Conclusion and implications

The Covid-19 pandemic helped double the number of firms repurchasing their own shares, and the increase was concentrated in March 2020. As many firms made every effort to prevent their share prices from declining, this could have imposed a direct or indirect impact on stabilizing share prices during the stock market turmoil in March. However, it’s also possible for the share buyback decision during the turmoil to do nothing more than a temporary measure for earning short-term capital gains. In other words, instead of canceling the repurchased shares, firms may sell those to the market again. Judging from the current share repurchase regulation, there’s a high possibility that the size of repurchases disclosed as part of a trust contract could be different from that of actual acquisition, which requires caution for investors.

All of those conditions call for investors to deepen their understanding about the differences in share repurchase arrangements between direct and indirect repurchases, or between a firm directly repurchasing shares and indirectly repurchasing them via trust contract. If those shares are sold again, instead of being canceled, it’s hard to expect a long-term enhancement in shareholder value. Short-term investors may enjoy temporary profits from disclosures on share repurchase, or the subsequent fall in the number of floating shares. However, this could hardly provide higher returns to longer-term shareholders. Because a trust contract gives a trustor firm too much discretion and excessively diverse decision-making opportunities, there’s always a possibility that the actual repurchase falls short of investor expectations. The hard-to-predict nature of this issue requires continuous attention and a cautious approach.

Also necessary in this area is further discussion about how to improve share repurchase regulation and disclosure systems. More regulatory effort should be made to improve investors’ predictability about share repurchase programs and to prevent firms from making irresponsible decisions. Last but not least, improvements in disclosure requirements will help investors to gain more information in a timely manner for making informed investment decisions.

1) Kim, Y.H. & Jung, S.C., 2008, Determinants of stock repurchase methods and the test of opportunistic behavior hypothesis, Korea Business Review 37(5), 1205-1232.

Korea Listed Companies Association, 2020, Practice guidelines on listed companies’ purchase, disposal, and cancelation of treasury stocks, KLCA 2020-10.

2) When the shares are returned under the trust contract, the firm’s actual repurchase occurs after the termination of expiration of the contract. Hence, the three-month period begins with a disclosure of the contract’s expiration or termination.

3) When a trustee sells (purchases) the treasury shares it purchased (sold) during the contract period, there should be at least a onemonth time span between the purchase and disposal.

4) Although firms do not disclose their actual repurchase transactions, it doesn’t mean the relevant information is non-public. It’s possible to check the acquisition or sale of treasury shares in the history of individual transactions provided by KIND. However, the transaction history only provides the date of transactions and the number of shares traded without the date of disclosure. The only way to figure out how each disclosure was implemented is to manually compare each disclosure with respective transaction history.