Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Korea’s Midterm Fiscal Operation Plan and Implications

Publication date Dec. 08, 2020

Summary

According to the midterm fiscal operation plan, Korea’s public debt ratio is projected to rise steeply as the nation faces an increase in fiscal expenditures this year in response to the Covid-19 shocks, and a decrease in fiscal revenues between 2021 and 2024. Such fiscal outlook provides contradicting short-term and mid-term implications. In a short run, slowed growth in fiscal expenditures will significantly reduce the effect of fiscal measures that have supported the economic growth so far. Also, an increase in government bond issuance will continue to impose an upward pressure on government bond yields. From the mid-term perspective, further effort should be made to keep fiscal soundness despite Korea’s faster rise in public debt ratio relative to advanced economies, while discussing the need to manage discretionary spending and to increase tax revenues for securing fiscal space to cope out any crisis in the future.

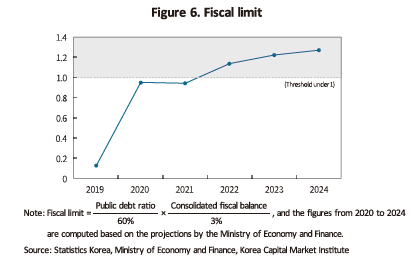

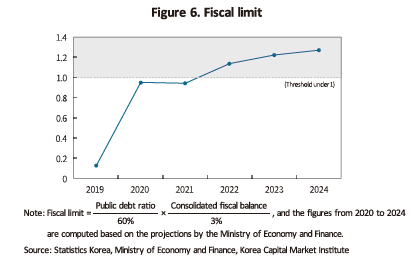

In September 2020, Korea’s Ministry of Economy and Finance unveiled the 2020-2024 National Fiscal Management Plan and the 2020-2060 Fiscal Outlook. Both of them try to provide a midterm projection on the government’s fiscal conditions at a time when Korea’s fiscal deficit grew this year as the country is fighting against Covid-19’s impacts on the real economy. According to the projection, the deficit in operational fiscal balance1) that excludes social security funds such as the National Pension will reach an average of 5.7% of GDP between 2021 and 2024, increasing the debt to GDP ratio from 43.5% in 2020 to 58.3% in 2024. Furthermore, the nation’s debt to GDP ratio is projected to rise to 81.1% in 2060 given the long-term decline in both population and economic growth. However, such a sharp rise in public debt reinforced the need for fiscal rules that could ensure fiscal policy to play a greater role while protecting fiscal soundness. This triggered the government to unveil its plans on October 5, 2020 for fiscal rules that would cap its debt-to-GDP ratio at 60%, and the consolidated fiscal balance deficit at 3%. Despite such policy effort, concerns have been lingering about the rules’ appropriateness and fiscal sustainability.

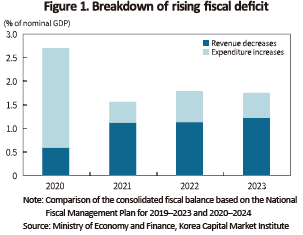

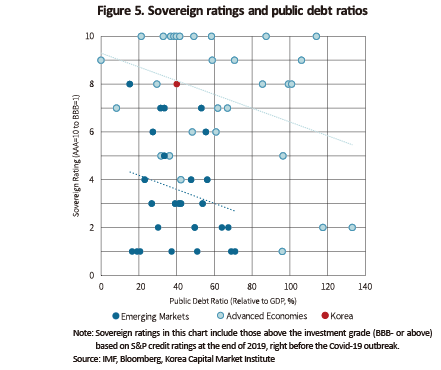

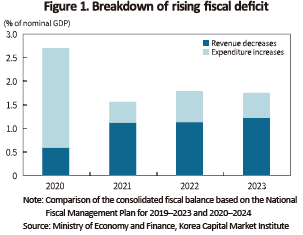

Why is Korea’s fiscal deficit rising so fast? As illustrated in Figure 1, a comparative look at the 2020-2024 National Fiscal Management Plan to the 2019-2013 plan unveiled in the previous year reveals that increased expenditures to cope with the pandemic widened the deficit in 2020. On the other hand, the rising deficit expected between 2021 and 2023 appears to stem from falling revenues. The economic slowdown resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic significantly cut fiscal revenues in 2020, and the growth in gross fiscal revenues between 2021 and 2023 is expected to be below the earlier outlook despite future economic recovery. Also, fiscal expenditures increased slightly from the 2019 plan despite the downward adjustment in outlook for fiscal revenues because Korea is expected to keep its expansionary fiscal stance for the Korean New Deal and other social safety net projects.

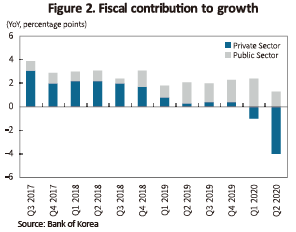

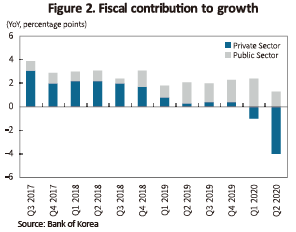

As Korea’s economy has yet to fully recover from the shocks from the pandemic, the above fiscal plan provides varying implications to the short-term and mid-term outlook. Among others, Korea’s fiscal contribution to economic growth is projected to fall sharply amid high uncertainties about the growth path. This is largely because fiscal expenditures in 2021 will increase only 0.3% to KRW 555.8 trillion from KRW 554.4 trillion in 2020 that includes four supplementary budget programs. As Korea’s economy entered into the contraction phase in the third quarter of 2017, the rate of increase in fiscal expenditures shot up immensely to 7.2% and 12% in 2018 and 2019, respectively. This has made fiscal contribution to growth gradually increase as shown in Figure 2. Especially in 2020, the economic shocks from the pandemic concentrated in close contact services, SMEs rather than large corporations, and the low income class particularly. Under the circumstances, there was imminent need to directly address the hardships of those hit hard by the pandemic, ideally via fiscal support instead of helping them to borrow more easily via monetary policy. The current outlook projects Korea’s economy to recover in the upcoming year under the vaccination scenario. However, the resilience of the private sector appears to matter significantly at a time government contribution to growth is expected to dwindle.

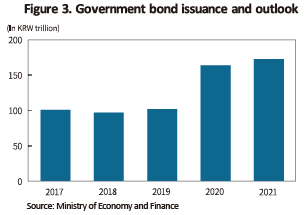

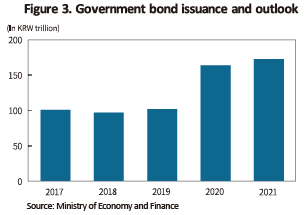

As did in 2020, Korea will issue a large amount of government bonds (KRW 172.9 trillion) that will go to replenish fiscal deficits in 2021. Such an increase in supply is expected to put an upward pressure on government bond yields. Earlier this year, the Bank of Korea launched five bond purchase operations to buy bonds worth of KRW 8 trillion directly from the market, aiming to address the supply pressure in the government bond market due to supplementary budgets, as well as the liquidity shortage from the Covid-19 pandemic. Given Korea’s current conditions for government bond issuance, Korea is expected to face growing calls in the market for the Bank of Korea to implement market stabilization measure via bond purchases, etc. as part of policy coordination with the government.

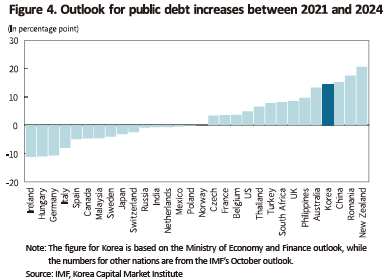

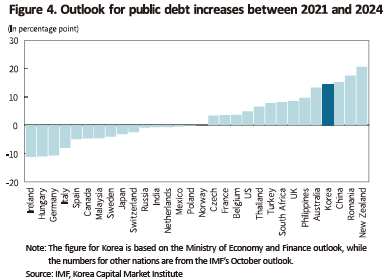

On top of the short-term response to fiscal cyclicality, a mid-term, fiscal soundness approach is needed to keep a close eye on the fiscal deficit and the public debt ratio. Although a proper level of the public debt ratio is currently at the heart of controversies, what’s more important is the pace of increase. According to the recent outlook by the IMF (October 2020), the Covid-19 pandemic and the shocks triggered fiscal expansion around the globe, which is expected to increase the public debt ratio of advanced economies by 20.2 percentage points (pp) in 2020, but to remain unchanged between 2021 and 2024. Although the fiscal policy stance varies across nations, such a projection primarily stems from the expectation that fiscal expenditures in euro-zone economies will gradually fall as the EU decided to suspend its fiscal rule—the Stability and Growth Pact—in response to the Covid-19 outbreak. However, the outlook by the Korean government2) predicts the public debt ratio to rise by 14.4 pp during the same period, which is as steep as that in New Zealand (20.5 pp), China (15.1 pp), and Australia (13.2 pp).

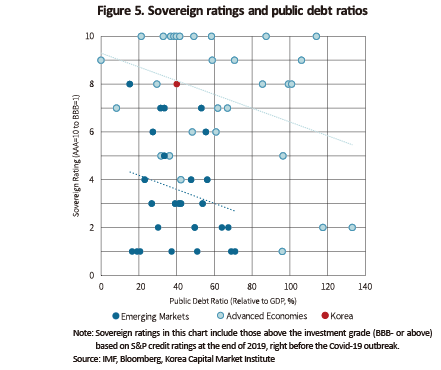

It’s worth noting that dampened fiscal soundness not only destabilizes a nation’s sovereign rating and capital flows, but also diminishes the fiscal space, a useful tool to address cyclical risk. A sovereign rating is determined by various factors including a nation’s projected public debt ratio, growth rate, current account balance, and geopolitical risk. However, recent studies have shown that public debt is a major factor behind sovereign ratings, and that public debt has been more important in the post-crisis era (Amstad & Packer, 2015; Boumparis et al., 2015). As illustrated in Figure 5, sovereign ratings and public debt ratios have a negative correlation. Also expected is a growing role and effectiveness of fiscal policy tools such as more direct financial support to the vulnerable in the recent macroeconomic environment where the prolonged low interest rate makes it difficult for the Bank of Korea to adjust the key interest rate as part of their monetary policy, and more policy responses aim to prevent deflation, instead of containing inflation. Against the backdrop, the worsening fiscal soundness is one of the factors that could diminish a nation’s capacity to address any crisis in the future.

Under the current circumstances, Korea’s short-term policy priority should be placed on fiscal expenditures aiming to recover from the shocks from the Covid-19 pandemic. However, what’s equally important is to have a longer-term target heading in the exactly opposite direction towards fiscal soundness. The fiscal rule that will take effect in 2025 is part of the efforts in that direction. For now, it’s crucial to stop any excessive fiscal tightening that would impact economic recovery, while trying to secure sufficient time before the fiscal rule kicks in. The current government outlook suggests that Korea will not be able to abide by the fiscal rule between 2022 and 2024, suggesting a precursor to severe fiscal tightening in the first year of the fiscal rule. This reinforces the need to manage the government’s discretionary spending, while on the other hand aiming to trigger wider social debates on how to increase revenues by tax increases, etc.

1) The operational budget balance that deducts social security funds from the consolidated fiscal balance was first introduced because there is no statutory obligation for the government to provide financial support to social security funds including the National Pension Fund, the Korea Teachers Pension Fund, Employment Insurance, and Workers’ Compensation. Another reason is the limited ability of the consolidated fiscal balance to provide a precise look at actual fiscal conditions because the social security funds post a surplus at least for now when the National Pension Fund has yet to fully begin paying out the benefits.

2) The pace of public debt increase is similar to the IMF forecast (13.9 pp). Note that the IMF’s public debt forecast for Korea in 2020 onward is higher than that of the Korean government because the fund’s growth forecast for Korea this year is lower than that of the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

References

Amstad, M., Packer, F., 2015, Sovereign ratings of advanced and emerging economies after the crisis, BIS Quarterly Review December 2015, 77-99.

Boumparis, P., Milas, C., Panagiotidis, T., 2015, Has the crisis affected the behavior of the rating agencies? Panel evidence from the Eurozone, Economics Letters 136, 118-124.

Why is Korea’s fiscal deficit rising so fast? As illustrated in Figure 1, a comparative look at the 2020-2024 National Fiscal Management Plan to the 2019-2013 plan unveiled in the previous year reveals that increased expenditures to cope with the pandemic widened the deficit in 2020. On the other hand, the rising deficit expected between 2021 and 2023 appears to stem from falling revenues. The economic slowdown resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic significantly cut fiscal revenues in 2020, and the growth in gross fiscal revenues between 2021 and 2023 is expected to be below the earlier outlook despite future economic recovery. Also, fiscal expenditures increased slightly from the 2019 plan despite the downward adjustment in outlook for fiscal revenues because Korea is expected to keep its expansionary fiscal stance for the Korean New Deal and other social safety net projects.

1) The operational budget balance that deducts social security funds from the consolidated fiscal balance was first introduced because there is no statutory obligation for the government to provide financial support to social security funds including the National Pension Fund, the Korea Teachers Pension Fund, Employment Insurance, and Workers’ Compensation. Another reason is the limited ability of the consolidated fiscal balance to provide a precise look at actual fiscal conditions because the social security funds post a surplus at least for now when the National Pension Fund has yet to fully begin paying out the benefits.

2) The pace of public debt increase is similar to the IMF forecast (13.9 pp). Note that the IMF’s public debt forecast for Korea in 2020 onward is higher than that of the Korean government because the fund’s growth forecast for Korea this year is lower than that of the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

References

Amstad, M., Packer, F., 2015, Sovereign ratings of advanced and emerging economies after the crisis, BIS Quarterly Review December 2015, 77-99.

Boumparis, P., Milas, C., Panagiotidis, T., 2015, Has the crisis affected the behavior of the rating agencies? Panel evidence from the Eurozone, Economics Letters 136, 118-124.