Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Electronic Trading in Global FX Market: Current State and Implications

Publication date Jun. 29, 2021

Summary

In the global foreign exchange market, the use of electronic trading has recently increased sharply, particularly in the dealer-to-customer market. Advancement in electronic trading systems has been shifting the structure of liquidity provision from the interbank market towards the dealer-to-customer market, and the emergence of diverse systems has helped the dealer-to-customer market participants to more actively engage in the FX market. By contrast, electronic trading in Korea’s FX market has been used limitedly in interbank transactions only, a trend starkly different from the global market. More recently, Korea sees the offshore won-dollar NDF transactions largely surpassing the onshore interbank spot exchange transactions, suggesting an impact of the changes in the global FX market on Korea. Given such changes and impacts of the global FX market, it is advisable that Korea improve its electronic trading infrastructure for FX transactions in a way that could induce the use of electronic trading in the dealer-to-customer market segment. Especially, Korea’s advancement in electronic trading in dealer-to-customer transactions is expected to produce positive outcomes such as enhancing customer convenience, increasing FX market liquidity, and promoting the efficiency in banks’ FX risk management, which in the long run will diversify the FX business scope for developing Korea’s financial services industry and the financial markets. However, the won currency’s partially international aspect requires a more cautious approach. One idea for market prudence would be to build a risk management system that could secure stability for the increased use of electronic trading in the FX market.

The increased electronic trading1) has triggered diverse structural changes in the global foreign exchange market. Despite the FX market’s over-the-counter nature, the proportion of electronic trading in the global FX market already surpassed that of voice trading. Moreover, advancement in electronic trading systems is also blurring the line between the interbank and dealer-to-customer markets. In line with such a global FX market trend, more attention is being paid to how to improve the use of electronic trading in Korea’s FX market. Under the circumstances, this article tries to explore the current state and the characteristics of electronic trading in the global FX market, which helps present the implications for Korea’s direction towards advanced electronic trading infrastructure.

Advancement of electronic trading in the FX market

The FX market structure is divided into two parts—the interbank market for large-scale, wholesale FX transactions, and the dealer-to-customer (retail) market whose liquidity is provided by dealer banks. Such a structural feature leaves a distinctive mark on the development of electronic trading the FX market: Electronic trading first took hold in the interbank market among a small number of large banks, then in the dealer-to-customer market among large banks only. Along with the development of electronic trading, the FX market has observed diverse changes. The boundary between the interbank and dealer-to-customer markets became blurred as more and more dealer-to-customer market transactions are recently electronically linked to the interbank market. Another change worth mentioning is the rise of non-bank entities serving as a primary provider of liquidity in the global FX market.

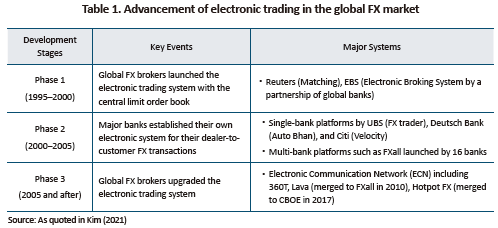

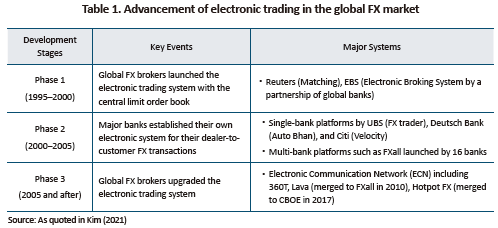

In the development stage of electronic trading in the global FX market, it was the mid 1990s when electronic trading began spreading in earnest with the introduction of Reuters Matching. Major global FX brokers such as EBS and Reuters launched a trading system that uses the interbank central limit order book.2) The system significantly enhanced trading efficiency, triggering a shift towards electronic trading in the interbank market (King et al., 2011). It was in the early 2000s when electronic trading began spreading in the FX dealer-to-customer market. This was largely fueled by the move of global banks to develop their own electronic trading system for dealer-to-customer transactions based on the liquidity they accumulated in the interbank segment that had been already enjoying the reduced cost of trading from the electronic trading system.3)

The pace of major global banks increasing the use of electronic trading in the FX market accelerated further in the mid 2000s when non-bank players one after another launched their own electronic trading platform for FX transactions. At that time, global FX brokers upgraded their system using the application programming interfaces (APIs)4) that enable systems to interact with each other, which helped more non-bank entities to participate in the FX market. More recently, the market sees the emergence of many ECNs that integrate a number of electronic trading systems for providing liquidity to dealer-to-customer transactions. The so-called “aggregator” links hundreds of FX trading systems of banks and non-banks, possibly providing FX trading execution services for not only large customers, but also small-scale retail customers.5)

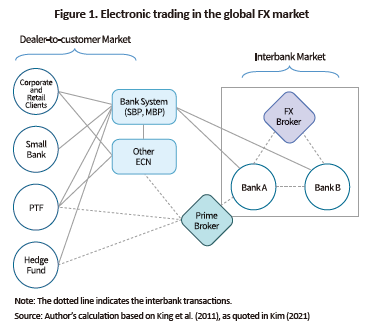

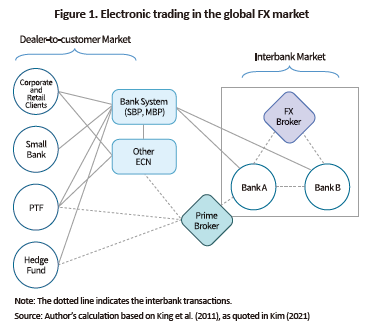

Currently, electronic trading in the global FX market is structured as illustrated in Figure 1. In the interbank market shown in the box—a market segment used to be participated by a small number of large banks, major global FX brokers provide multilateral electronic trading services via their own platform. In the dealer-to-customer market, banks’ own SBP and MBP use the ECN to provide real-time interbank quotations and low-cost execution. More recently, dealer-to-customer market participants can trade also in the interbank market. Some large banks provide prime brokerage services enabling their customers to participate in interbank transactions under the bank’s name. As such, more and more large-scale hedge funds and other principal trading firms (PTFs)6) are participating in the interbank market (the dotted line).

Global FX market transactions: Current state and characteristics

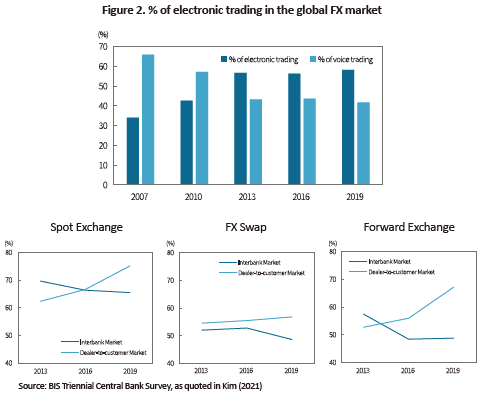

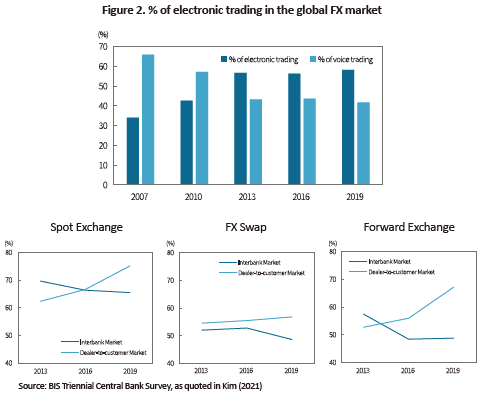

According to the Bank of International Settlement (BIS), the share of electronic trading in total FX transactions accounted for 57% in 2019. Since 2013, the share of electronic trading has surpassed that of voice trading.7) In particular, the proportion of electronic trading was even higher at about 72% in the spot exchange market whose transaction structure is simpler than other FX products. More recently, the electronic trading of forward exchanges and FX swaps is increasing further largely in the dealer-to-customer market. In the forward exchanges in the dealer-to-customer market, the increase in electronic trading of non-deliverable forwards (NDFs) likely contributed to the rising share of electronic trading.8)

Such a rise in electronic trading in the global FX market is triggering a change in trading behavior that used to be driven by large-scale banks. According to the recent BIS data, the ratio of dealer-to-customer transactions in the overall FX transactions stood at about 62% as of 2019. Since 2007, FX trading volume in the dealer-to-customer market has exceeded that in the interbank market. This is largely because the increased use of electronic trading in bank’s dealer-to-customer transactions led to increased internalization of those transactions. In other words, there is a decrease in demand for interbank transactions that are executed for the purpose of clearing the FX positions linked to their dealer-to-customer transactions. On the other hand, banks see an increase in the share of internalized transactions for netting their dealer-to-customer market positions within their own electronic trading platform used for dealer-to-customer transactions. Schrimpf & Sushko (2019) found that the proportion of internalized transactions stood at 60% to 83% in European and US banks, respectively, suggesting that most of their dealer-to-customer transactions could be netted in their internal electronic trading system.

More recently, the market observes a rapid increase in the trading volume of non-bank PTFs that capitalize on a number of electronic trading platforms for providing liquidity in the FX market. Using a diversity of electronic trading platforms, PTFs provide liquidity to the dealer-to-customer market. Especially, they appear to play a significant role in processing most of the FX transactions by large-scale buyside clients such as hedge funds. To sum up, the role large-scale banks used to play as an FX liquidity provider is being replaced by non-bank FX electronic trading platforms whose strength lies in the speedy execution of electronic trades. A recent survey revealed that major PTFs accounted for about 32% of the global spot exchange transactions, according to which four out of ten firms recording the highest trading volume were algorithm-based PTFs.9)

Implications for Korea’s FX market

Although Korea’s FX market is primarily led by authorized foreign exchange banks, the rise of electronic trading and the resultant changes taking place in the global FX could partially affect Korea’s FX market. For example, Korea has recently seen offshore won-dollar NDF transactions largely surpassing onshore interbank spot transactions. This means the improvement in the NDF electronic trading system encourages a more diverse set of entities to participate in the won-dollar NDF market. By contrast, the spot exchange transactions in Korea’s interbank market have stalled since 2007, implying the relative decrease in Korea’s FX market liquidity despite the increase in domestic investors’ outbound portfolio investments during the same period. This is also raising some concerns about the negative impacts such as the offshore market dominating Korea’s FX market, and the shift of power in price discovery of the won-dollar FX rate.

In terms of the use of electronic trading, Korea’s FX market is going through phase 2 in the stage of global FX market development. Although Korea saw a large jump in electronic trading in the interbank market when FX brokers introduced electronic broking in the early 2000s, the use of electronic trading for dealer-to-customer transactions is still insignificant. Some domestic banks have been launching electronic trading systems for their retail and corporate clients, but most of these systems are barely used due to their limited functions covering small-scale FX transactions only. In particular, those systems lack the API linkage between the interbank and dealer-to-customer markets, which limits the system’s scalability to dealer-to-customer transactions. Such characteristics largely differ from the global FX market trend where electronic trading is being more widely used for dealer-to-customer transactions.

In general, the rise of electronic trading leads to positive outcomes, for example, enhancing trade efficiency and improving data transparency. Major studies in this area argue that the positive effects of electronic trading dwarf the negative effects in the FX market. For example, the wider use of electronic trading is found to help improve FX market liquidity (Bloomfield & O’Hara, 2000) and lower bid-ask spreads (Ding & Hiltrop, 2010). Notably, computerization of orders via electronic trading is found to lower the cost of transactions, and promote business efficiency by lowering the risks of manual entries.

From that perspective, Korea’s FX market needs to further increase the use of electronic trading as follows. First, it is worth considering using electronic trading in FX transactions for improving Korea’s FX market liquidity given that Korean residents have been increasing their exposure to outbound portfolio investment. It is particularly important for Korea to develop a new source of liquidity provision in the dealer-to-customer market because major dealer banks’ liquidity provision capacity has been limited since the global financial crisis. Second, further effort should be made to improve Korea’s electronic trading infrastructure for enhancing its FX market competitiveness given the abrupt rise in offshore NDF transactions amid the global FX market trend leaning towards electronic trading. Third, the use of electronic trading for FX transactions would also give a boost to FX business of Korea’s financial services industry. Considering that non-bank entities are using electronic trading to increase their engagement in the FX market, more effort to improve electronic trading infrastructure is expected to help Korea’s financial services industry to diversify their FX business scope and further advance the financial markets.

However, the partially international aspect of the won currency requires a more cautious approach that would fully take into account the health of Korea’s FX market. A better electronic trading system that would make FX trading more convenient would make double-sided effects of improving liquidity conditions while at the same time increasing speculative trading. That reinforces the need for a risk management system that would secure market stabilization if electronic trading fully takes hold in the FX market.

1) In this article, electronic trading in the FX market refers to an FX transaction via an electronic trading platform of a bank with another bank (in the interbank market), and its retail and corporate client (in the dealer-to-customer market).

2) The electronic trading system based on the central limit order book is an electronic order execution system widely used in securities and commodity exchanges. It supports various functions such as real time quotation, limit order, low-cost execution, back-office automation, etc.

3) Banks’ electronic trading system for dealer-to-customer transactions is classified into the single bank trading platform (SBP) that is a system specific to a certain bank only, and the multi bank trading platform (MBP) that is a common system shared by several banks.

4) The FX API refers to a server-to-server communication interface that connects the interbank and electronic trading systems via a dedicated network for helping electronic linkages for quotation, execution, and inquiries.

5) One of the exemplary ECN providers is 360T that offers integrated services by linking about 400 bank and non-bank FX trading platforms.

6) A PTF is a specialized, algorithm-based investment firm that provides liquidity via high frequency trading strategies. It is widely known as a high frequency trader (HFT), but the Futures Industry Association officially uses the term PTF, reflecting the member firms’ concerns about the negative image of HFT.

7) According to the BIS statistics, voice trading refers to all types of trading other than phone trading that includes trading via text messages.

8) Schrimpf & Sushko (2019) found that NDF trading increased greatly in 2016 when EBS, a major global FX platform, launched its electronic trading service in this market segment.

9) Euromoney (2019) reported that, the list of top 10 firms with the highest spot exchange trading volume had four PTFs including XTX Markets raked second with 9.6% in market share, and HC Tech, Jump Trading, and Citadel Securities.

References

Bloomfield, R., O’Hara, M, 2000, Can transparent markets survive? Journal of Financial Economics 55, 425-459.

Ding, L., Hiltrop, J., 2010, The electronic trading systems and bid-ask spreads in the foreign exchange market, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 20(4), 323-345.

Euromoney, 2019, Foreign exchange survey 2019: electronic trading.

King, M., Osler, C., Rime, D., 2011, Foreign exchange market structure, players and evolution, Norges Bank Working Paper 2011(10).

Schrimpf, A., Sushko, V., 2019, FX trade execution: complex and highly fragmented, BIS Quarterly Review 2019(12).

(Korean)

Kim, H.S., 2021, Rise of electronic trading: The changes and implications for the FX market, KCMI Issue Paper 21-01.

Advancement of electronic trading in the FX market

The FX market structure is divided into two parts—the interbank market for large-scale, wholesale FX transactions, and the dealer-to-customer (retail) market whose liquidity is provided by dealer banks. Such a structural feature leaves a distinctive mark on the development of electronic trading the FX market: Electronic trading first took hold in the interbank market among a small number of large banks, then in the dealer-to-customer market among large banks only. Along with the development of electronic trading, the FX market has observed diverse changes. The boundary between the interbank and dealer-to-customer markets became blurred as more and more dealer-to-customer market transactions are recently electronically linked to the interbank market. Another change worth mentioning is the rise of non-bank entities serving as a primary provider of liquidity in the global FX market.

In the development stage of electronic trading in the global FX market, it was the mid 1990s when electronic trading began spreading in earnest with the introduction of Reuters Matching. Major global FX brokers such as EBS and Reuters launched a trading system that uses the interbank central limit order book.2) The system significantly enhanced trading efficiency, triggering a shift towards electronic trading in the interbank market (King et al., 2011). It was in the early 2000s when electronic trading began spreading in the FX dealer-to-customer market. This was largely fueled by the move of global banks to develop their own electronic trading system for dealer-to-customer transactions based on the liquidity they accumulated in the interbank segment that had been already enjoying the reduced cost of trading from the electronic trading system.3)

Currently, electronic trading in the global FX market is structured as illustrated in Figure 1. In the interbank market shown in the box—a market segment used to be participated by a small number of large banks, major global FX brokers provide multilateral electronic trading services via their own platform. In the dealer-to-customer market, banks’ own SBP and MBP use the ECN to provide real-time interbank quotations and low-cost execution. More recently, dealer-to-customer market participants can trade also in the interbank market. Some large banks provide prime brokerage services enabling their customers to participate in interbank transactions under the bank’s name. As such, more and more large-scale hedge funds and other principal trading firms (PTFs)6) are participating in the interbank market (the dotted line).

According to the Bank of International Settlement (BIS), the share of electronic trading in total FX transactions accounted for 57% in 2019. Since 2013, the share of electronic trading has surpassed that of voice trading.7) In particular, the proportion of electronic trading was even higher at about 72% in the spot exchange market whose transaction structure is simpler than other FX products. More recently, the electronic trading of forward exchanges and FX swaps is increasing further largely in the dealer-to-customer market. In the forward exchanges in the dealer-to-customer market, the increase in electronic trading of non-deliverable forwards (NDFs) likely contributed to the rising share of electronic trading.8)

More recently, the market observes a rapid increase in the trading volume of non-bank PTFs that capitalize on a number of electronic trading platforms for providing liquidity in the FX market. Using a diversity of electronic trading platforms, PTFs provide liquidity to the dealer-to-customer market. Especially, they appear to play a significant role in processing most of the FX transactions by large-scale buyside clients such as hedge funds. To sum up, the role large-scale banks used to play as an FX liquidity provider is being replaced by non-bank FX electronic trading platforms whose strength lies in the speedy execution of electronic trades. A recent survey revealed that major PTFs accounted for about 32% of the global spot exchange transactions, according to which four out of ten firms recording the highest trading volume were algorithm-based PTFs.9)

Implications for Korea’s FX market

Although Korea’s FX market is primarily led by authorized foreign exchange banks, the rise of electronic trading and the resultant changes taking place in the global FX could partially affect Korea’s FX market. For example, Korea has recently seen offshore won-dollar NDF transactions largely surpassing onshore interbank spot transactions. This means the improvement in the NDF electronic trading system encourages a more diverse set of entities to participate in the won-dollar NDF market. By contrast, the spot exchange transactions in Korea’s interbank market have stalled since 2007, implying the relative decrease in Korea’s FX market liquidity despite the increase in domestic investors’ outbound portfolio investments during the same period. This is also raising some concerns about the negative impacts such as the offshore market dominating Korea’s FX market, and the shift of power in price discovery of the won-dollar FX rate.

In terms of the use of electronic trading, Korea’s FX market is going through phase 2 in the stage of global FX market development. Although Korea saw a large jump in electronic trading in the interbank market when FX brokers introduced electronic broking in the early 2000s, the use of electronic trading for dealer-to-customer transactions is still insignificant. Some domestic banks have been launching electronic trading systems for their retail and corporate clients, but most of these systems are barely used due to their limited functions covering small-scale FX transactions only. In particular, those systems lack the API linkage between the interbank and dealer-to-customer markets, which limits the system’s scalability to dealer-to-customer transactions. Such characteristics largely differ from the global FX market trend where electronic trading is being more widely used for dealer-to-customer transactions.

In general, the rise of electronic trading leads to positive outcomes, for example, enhancing trade efficiency and improving data transparency. Major studies in this area argue that the positive effects of electronic trading dwarf the negative effects in the FX market. For example, the wider use of electronic trading is found to help improve FX market liquidity (Bloomfield & O’Hara, 2000) and lower bid-ask spreads (Ding & Hiltrop, 2010). Notably, computerization of orders via electronic trading is found to lower the cost of transactions, and promote business efficiency by lowering the risks of manual entries.

From that perspective, Korea’s FX market needs to further increase the use of electronic trading as follows. First, it is worth considering using electronic trading in FX transactions for improving Korea’s FX market liquidity given that Korean residents have been increasing their exposure to outbound portfolio investment. It is particularly important for Korea to develop a new source of liquidity provision in the dealer-to-customer market because major dealer banks’ liquidity provision capacity has been limited since the global financial crisis. Second, further effort should be made to improve Korea’s electronic trading infrastructure for enhancing its FX market competitiveness given the abrupt rise in offshore NDF transactions amid the global FX market trend leaning towards electronic trading. Third, the use of electronic trading for FX transactions would also give a boost to FX business of Korea’s financial services industry. Considering that non-bank entities are using electronic trading to increase their engagement in the FX market, more effort to improve electronic trading infrastructure is expected to help Korea’s financial services industry to diversify their FX business scope and further advance the financial markets.

However, the partially international aspect of the won currency requires a more cautious approach that would fully take into account the health of Korea’s FX market. A better electronic trading system that would make FX trading more convenient would make double-sided effects of improving liquidity conditions while at the same time increasing speculative trading. That reinforces the need for a risk management system that would secure market stabilization if electronic trading fully takes hold in the FX market.

1) In this article, electronic trading in the FX market refers to an FX transaction via an electronic trading platform of a bank with another bank (in the interbank market), and its retail and corporate client (in the dealer-to-customer market).

2) The electronic trading system based on the central limit order book is an electronic order execution system widely used in securities and commodity exchanges. It supports various functions such as real time quotation, limit order, low-cost execution, back-office automation, etc.

3) Banks’ electronic trading system for dealer-to-customer transactions is classified into the single bank trading platform (SBP) that is a system specific to a certain bank only, and the multi bank trading platform (MBP) that is a common system shared by several banks.

4) The FX API refers to a server-to-server communication interface that connects the interbank and electronic trading systems via a dedicated network for helping electronic linkages for quotation, execution, and inquiries.

5) One of the exemplary ECN providers is 360T that offers integrated services by linking about 400 bank and non-bank FX trading platforms.

6) A PTF is a specialized, algorithm-based investment firm that provides liquidity via high frequency trading strategies. It is widely known as a high frequency trader (HFT), but the Futures Industry Association officially uses the term PTF, reflecting the member firms’ concerns about the negative image of HFT.

7) According to the BIS statistics, voice trading refers to all types of trading other than phone trading that includes trading via text messages.

8) Schrimpf & Sushko (2019) found that NDF trading increased greatly in 2016 when EBS, a major global FX platform, launched its electronic trading service in this market segment.

9) Euromoney (2019) reported that, the list of top 10 firms with the highest spot exchange trading volume had four PTFs including XTX Markets raked second with 9.6% in market share, and HC Tech, Jump Trading, and Citadel Securities.

References

Bloomfield, R., O’Hara, M, 2000, Can transparent markets survive? Journal of Financial Economics 55, 425-459.

Ding, L., Hiltrop, J., 2010, The electronic trading systems and bid-ask spreads in the foreign exchange market, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 20(4), 323-345.

Euromoney, 2019, Foreign exchange survey 2019: electronic trading.

King, M., Osler, C., Rime, D., 2011, Foreign exchange market structure, players and evolution, Norges Bank Working Paper 2011(10).

Schrimpf, A., Sushko, V., 2019, FX trade execution: complex and highly fragmented, BIS Quarterly Review 2019(12).

(Korean)

Kim, H.S., 2021, Rise of electronic trading: The changes and implications for the FX market, KCMI Issue Paper 21-01.