OPINION

2021 Aug/24

Changing Environments of Monetary Policy Stance and Its Implications on Macroprudentiality

Aug. 24, 2021

PDF

- Summary

- With the upward trend of global inflation to continue into this year, major economies including the US are expected to witness a change in monetary policy stance and transition towards higher interest rates in the near future. Amid recent price hikes, Korea is also experiencing intensified financial imbalance where private sector debt has surged on the back of the increase in liquidity and leverage with prices of assets like property and stocks being on the rise. This reinforces the need for raising the policy interest rate. However, a steep rise in interest rates could aggravate interest payment burden of economic agents and thus, hinder domestic demand from entering a recovery phase. Also noteworthy is the possibility that rising inflation would trigger greater volatility of the financial market. Therefore, a monetary policy shift should be aligned with an inflation target by reflecting visible signs of recovery in the real economy and the job market, with focus on maintaining macro-prudentiality.

Despite the resurgence of Covid 19 and uncertainties over when the pandemic will end, global monetary policies are entering a transition phase on hopes of economic recovery. The US Fed is pondering when to begin the so-called tapering—cutback on liquidity that has been pumped into the market, whereas the market expects the Fed to move up its timeline for lifting the policy interest rate. With the continued monetary easing, the Bank of Korea has been considering whether to raise the policy interest rate in the course of this year. Given such a transition in global monetary policies has been primarily affected by rising inflation around the world, any shift in policy stance is likely to have an impact on macro-prudentiality or financial stability.

In line with this view, this article intends to explore the current inflation trend in Korea and abroad, to take a brief look at a steep surge in private debt, volatility of capital flows and a rise in asset prices, all of which could influence macroeconomic prudence depending on changes in monetary policy and to present relevant implications.

Current State of inflation and monetary policy trend in Korea and abroad

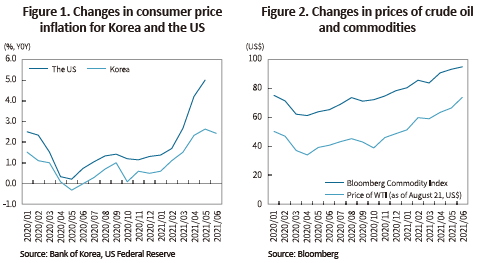

In terms of prices in the US for 2021, the consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI) rose 4.9% and 6.5% respectively on a YoY basis in May, following the upward trend in March and April. This raises the possibility that current inflation may persist longer than initially anticipated. Emerging economies in Asia have mainly seen a sharp rise in producer prices, with India and China posting a YoY increase in PPI of 12.9% and 9.0%, respectively in May. This indicates that such PPI increases in two major markets are expected to push up CPI with an interval of time. In Korea as well, consumer prices rose 2.3% in April and 2.6% in May this year, surpassing 2% of the inflation target while core inflation that excludes changes in volatile sectors such as food and energy hovered over 1% during the same period.

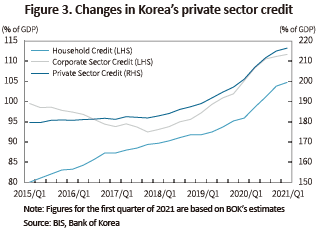

The global inflationary trend is primarily attributable to supply-side factors including price hikes in international crude oil or raw materials. Crude oil prices (based on West Texas Intermediate (WTI)) more than doubled to $73.5 per barrel in late June of 2021, from $33.7 per barrel at the end of April 2020, with the global commodity index including metals or grains posting a 1.5-fold increase over the same period. Other factors behind lingering high inflation are delayed recovery in global supply chains for some articles like semiconductors and upward pressure on wages. Furthermore, expected inflation has been driven up by expectations for economic recovery on the back of rising vaccination rates, together with abundant liquidity provided through monetary easing policies, which adds fuel to inflationary pressure. As for the Korean economy, additional factors of rising inflation are higher prices of agriculture and livestock products and upward movement in monthly rent and long-term housing rental deposit.

The US and other major economies regard such rising prices as a transitory trend. They predict that the recent pace of inflation would slow down in the second half and into the end of this year, because higher inflation stems from base effect of the spread of Covid-19 during the same period of last year. However, amid the possibility that inflation—initially anticipated as a temporary price hike—will be prolonged, the circumstances surrounding global monetary policies are undergoing changes. If the pandemic shows signs of abating going forward, the pent-up private demand is going to burst out and companies are likely to resume their investment in tandem with recovery of global economic activities. In this case, upward pressure on demand plus existing supply-side factors would cause inflation to persist longer than expected. Even some raise the prospect that a global commodities boom could turn into a supercycle.

Monetary authorities who should proactively formulate monetary policy tools to mitigate inflation fears have already sent the market a signal of a major policy shift. With growing concerns over rising inflation, it seems inevitable to implement the policy transition, although it may take a long period of time before the real economy and the job market reach a full recovery. Against this backdrop, the market has anticipated that the Fed would change its monetary policy direction earlier than expected. In a recent survey conducted in March 2021, for instance, the majority of respondents said that the Fed would adjust the policy interest rate in 2023, whereas the proportion of respondents who predicted such adjustment to occur in 2022 significantly increased in the June survey. Korea would also see its monetary policy stance move gradually from the current expansionary mode toward a normal setting. Thus, it is required to pay keen attention to various risk factors to maintain macro-prodentiality.

Factors undermining macro-prodentiality in case of a monetary policy shift

Compared with rising interest rates immediately after the global financial crisis, interest rate hikes that Korea is going to experience reflect a particular situation of Covid-19. As vast liquidity has been poured in through aggressive fiscal and monetary policies, the private sector debt as well as prices of assets such as property or stocks have surged at a rapid pace, which has made financial imbalance more severe than ever before. In this regard, the following factors should be taken into account with caution in order to keep macroeconomic prudence before a major transition in monetary policy takes place.

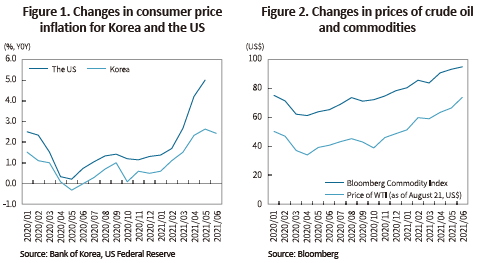

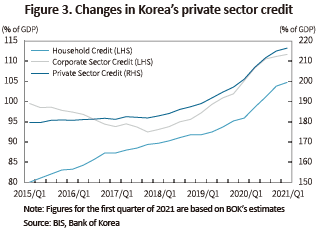

First, the levels of household and corporate debt have been rising at a rapid pace. According to the data released by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), as of the end of 2020 Korea reported 103.8% of household credit, 111.1% of corporate credit and 214.9% of the total private sector debt in terms of the share of GDP, all of which have increased at a faster pace than those of any major economies. In addition, this upward movement is estimated to have continued into the first quarter of 2021.1) In terms of household debt, home mortgage loans taken out from banks have dramatically increased, together with loans from non-banking financial institutions to meet growing demand for stock investment funds or to make up for reduced income. As a result, the Debt to Income (DTI) ratio is rapidly climbing. Although companies are relatively less burdened to pay off principal and interest with the Debt Service Ratio (DSR) remaining low, the proportion of firms whose operating income is insufficient to pay interest rose to 40% in 2020, from the 2019 level of 39%.

Under these circumstances, higher interest rates would cause households and businesses to become financially stressed, further driving up the DTI ratio. This could undermine their spending power and serve as an obstacle to economic recovery, which thus, may have an adverse impact on macro-prudentiality. It would take a considerable amount of time before the job market fully recovers from the pandemic aftershocks and labor income shows clear signs of improvement. During the period, however, rising interest rates could aggravate interest payment burden and then render loans of the low-income group and the financially disadvantaged ill-performing. As recovery in business activities would vary in degree by sector and industry, companies would be subject to different debt burdens.

Second, interest rate hikes in the US are anticipated to bring about changes to global capital flows. Lower liquidity and rising interest rates around the globe make it hard to rule out the possibility that Korea and other emerging markets would suffer capital outflows and greater volatility of the financial markets. In the aftermath of the end to the US quantitative easing in 2013, a significant number of emerging economies saw their stock prices and currency valuations plummet due to capital outflows. What is noteworthy is that this chain of events expanded volatility of their financial markets and aggravated economic predicament, thereby triggering the global financial market to become highly volatile.

As capital injected to emerging markets after the outbreak of Covid-19 has been heavily invested in bonds, instead of stocks, such large-scale capital flight as the previous one is less likely to occur. However, the spread of variants is increasing uncertainties over future developments on the pandemic or when the real economy rebounds, likely causing greater volatility to linger in the financial market for quite some period of time. In particular, risk preferences of global investors tend to sensitively respond to the global situation of coronavirus. Therefore, if some countries have fragile economic fundamentals or a serious financial instability, or there is a huge gap between their interest rates and those of advanced economies, they would come under a lot of pressure of capital outflows.

Third, potential decline in asset prices driven by higher interest rates would pose a threat to macroeconomic prudence. Korea’s housing prices have continued to surge, buoyed by supply and demand imbalance created by supply shortages and expectations for additional price hikes. This has sharply pushed up the Price to Income (PIR) ratio. Furthermore, the exposure of households and firms to real estate financing jumped to KRW 2,343.9 trillion as of late March of 2021, posting an 11.2% YoY increase.2) This indicates that any fall in property prices would raise risks of ill-performing housing loans.

Meanwhile, the KOSPI has soared more than 120% from the low point since the onset of the pandemic, reaching a historic high of 3,305.2 points for 7.3 days in early July this year. As a result, both the Price Earnings Ratio (PER) and the Price Book-value Ratio (PBR) have been surpassing the long-term prospects by large margins. Bullish stock prices are attributed to improvement in key economic indices in Korea and abroad, the increase in Korean firms’ estimated profits and enhanced investor sentiment stemming from large-scale infrastructure investment projects in the US, on the back of continued expectations for economic recovery. Also, other important factors—vast liquidity provided through monetary easing and active leverage investing—appear to be at play. For these reasons, it is worth noting that if any change in monetary policy stance leads to decreased liquidity and higher interest rates, it could affect investor sentiment and thus, result in asset price adjustment.

Implications

In coping with the Covid-19 crisis with aggressive policy tools, Korea has seen an acute increase in both market liquidity and private sector debt. In addition, prices of assets such as residential property and stocks have dramatically climbed, further worsening financial imbalance. With the US monetary policy set to enter a normal mode in the near future, it is advisable for Korea to raise its policy interest rate to address financial imbalance and minimize the probability of capital outflow.

Unlike in the past, however, recent asset price hikes are significantly dependent on plenty of liquidity and leverage. Hence, what is necessary is to carefully determine the timing and pace of a monetary policy shift only when the real economy and the job market are poised for recovery. A steep rise in interest rates is likely to lay a heavy burden of interest payment on economic players and act as an impediment to a rebound in domestic consumption. Also, it could lead to a plunge in asset prices and greater volatility of the financial market, likely undermining macro-prudentiality. As for private sector debt, it is recommendable to reinforce a support system for the financially disadvantaged and help companies enhance productivity and make more profits in order to facilitate recovery in household income to mitigate potential risks, rather than deliberately seeking debt reduction. Also necessary is to implement monetary policy instruments in harmony with relevant policy measures in that a monetary policy alone cannot resolve problems of financial imbalance intensified by rising housing prices and varying degrees of recovery by business type.

1) According to the Financial Stability Report released by the Bank of Korea (in June 2021), the private sector credit is estimated at 216.3% as a percent of GDP as of the end of the first quarter this year.

2) With regard to this, please refer to the Financial Stability Report published in June 2021 by the Bank of Korea.

In line with this view, this article intends to explore the current inflation trend in Korea and abroad, to take a brief look at a steep surge in private debt, volatility of capital flows and a rise in asset prices, all of which could influence macroeconomic prudence depending on changes in monetary policy and to present relevant implications.

Current State of inflation and monetary policy trend in Korea and abroad

In terms of prices in the US for 2021, the consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI) rose 4.9% and 6.5% respectively on a YoY basis in May, following the upward trend in March and April. This raises the possibility that current inflation may persist longer than initially anticipated. Emerging economies in Asia have mainly seen a sharp rise in producer prices, with India and China posting a YoY increase in PPI of 12.9% and 9.0%, respectively in May. This indicates that such PPI increases in two major markets are expected to push up CPI with an interval of time. In Korea as well, consumer prices rose 2.3% in April and 2.6% in May this year, surpassing 2% of the inflation target while core inflation that excludes changes in volatile sectors such as food and energy hovered over 1% during the same period.

The global inflationary trend is primarily attributable to supply-side factors including price hikes in international crude oil or raw materials. Crude oil prices (based on West Texas Intermediate (WTI)) more than doubled to $73.5 per barrel in late June of 2021, from $33.7 per barrel at the end of April 2020, with the global commodity index including metals or grains posting a 1.5-fold increase over the same period. Other factors behind lingering high inflation are delayed recovery in global supply chains for some articles like semiconductors and upward pressure on wages. Furthermore, expected inflation has been driven up by expectations for economic recovery on the back of rising vaccination rates, together with abundant liquidity provided through monetary easing policies, which adds fuel to inflationary pressure. As for the Korean economy, additional factors of rising inflation are higher prices of agriculture and livestock products and upward movement in monthly rent and long-term housing rental deposit.

Monetary authorities who should proactively formulate monetary policy tools to mitigate inflation fears have already sent the market a signal of a major policy shift. With growing concerns over rising inflation, it seems inevitable to implement the policy transition, although it may take a long period of time before the real economy and the job market reach a full recovery. Against this backdrop, the market has anticipated that the Fed would change its monetary policy direction earlier than expected. In a recent survey conducted in March 2021, for instance, the majority of respondents said that the Fed would adjust the policy interest rate in 2023, whereas the proportion of respondents who predicted such adjustment to occur in 2022 significantly increased in the June survey. Korea would also see its monetary policy stance move gradually from the current expansionary mode toward a normal setting. Thus, it is required to pay keen attention to various risk factors to maintain macro-prodentiality.

Factors undermining macro-prodentiality in case of a monetary policy shift

Compared with rising interest rates immediately after the global financial crisis, interest rate hikes that Korea is going to experience reflect a particular situation of Covid-19. As vast liquidity has been poured in through aggressive fiscal and monetary policies, the private sector debt as well as prices of assets such as property or stocks have surged at a rapid pace, which has made financial imbalance more severe than ever before. In this regard, the following factors should be taken into account with caution in order to keep macroeconomic prudence before a major transition in monetary policy takes place.

First, the levels of household and corporate debt have been rising at a rapid pace. According to the data released by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), as of the end of 2020 Korea reported 103.8% of household credit, 111.1% of corporate credit and 214.9% of the total private sector debt in terms of the share of GDP, all of which have increased at a faster pace than those of any major economies. In addition, this upward movement is estimated to have continued into the first quarter of 2021.1) In terms of household debt, home mortgage loans taken out from banks have dramatically increased, together with loans from non-banking financial institutions to meet growing demand for stock investment funds or to make up for reduced income. As a result, the Debt to Income (DTI) ratio is rapidly climbing. Although companies are relatively less burdened to pay off principal and interest with the Debt Service Ratio (DSR) remaining low, the proportion of firms whose operating income is insufficient to pay interest rose to 40% in 2020, from the 2019 level of 39%.

Second, interest rate hikes in the US are anticipated to bring about changes to global capital flows. Lower liquidity and rising interest rates around the globe make it hard to rule out the possibility that Korea and other emerging markets would suffer capital outflows and greater volatility of the financial markets. In the aftermath of the end to the US quantitative easing in 2013, a significant number of emerging economies saw their stock prices and currency valuations plummet due to capital outflows. What is noteworthy is that this chain of events expanded volatility of their financial markets and aggravated economic predicament, thereby triggering the global financial market to become highly volatile.

As capital injected to emerging markets after the outbreak of Covid-19 has been heavily invested in bonds, instead of stocks, such large-scale capital flight as the previous one is less likely to occur. However, the spread of variants is increasing uncertainties over future developments on the pandemic or when the real economy rebounds, likely causing greater volatility to linger in the financial market for quite some period of time. In particular, risk preferences of global investors tend to sensitively respond to the global situation of coronavirus. Therefore, if some countries have fragile economic fundamentals or a serious financial instability, or there is a huge gap between their interest rates and those of advanced economies, they would come under a lot of pressure of capital outflows.

Third, potential decline in asset prices driven by higher interest rates would pose a threat to macroeconomic prudence. Korea’s housing prices have continued to surge, buoyed by supply and demand imbalance created by supply shortages and expectations for additional price hikes. This has sharply pushed up the Price to Income (PIR) ratio. Furthermore, the exposure of households and firms to real estate financing jumped to KRW 2,343.9 trillion as of late March of 2021, posting an 11.2% YoY increase.2) This indicates that any fall in property prices would raise risks of ill-performing housing loans.

Meanwhile, the KOSPI has soared more than 120% from the low point since the onset of the pandemic, reaching a historic high of 3,305.2 points for 7.3 days in early July this year. As a result, both the Price Earnings Ratio (PER) and the Price Book-value Ratio (PBR) have been surpassing the long-term prospects by large margins. Bullish stock prices are attributed to improvement in key economic indices in Korea and abroad, the increase in Korean firms’ estimated profits and enhanced investor sentiment stemming from large-scale infrastructure investment projects in the US, on the back of continued expectations for economic recovery. Also, other important factors—vast liquidity provided through monetary easing and active leverage investing—appear to be at play. For these reasons, it is worth noting that if any change in monetary policy stance leads to decreased liquidity and higher interest rates, it could affect investor sentiment and thus, result in asset price adjustment.

Implications

In coping with the Covid-19 crisis with aggressive policy tools, Korea has seen an acute increase in both market liquidity and private sector debt. In addition, prices of assets such as residential property and stocks have dramatically climbed, further worsening financial imbalance. With the US monetary policy set to enter a normal mode in the near future, it is advisable for Korea to raise its policy interest rate to address financial imbalance and minimize the probability of capital outflow.

Unlike in the past, however, recent asset price hikes are significantly dependent on plenty of liquidity and leverage. Hence, what is necessary is to carefully determine the timing and pace of a monetary policy shift only when the real economy and the job market are poised for recovery. A steep rise in interest rates is likely to lay a heavy burden of interest payment on economic players and act as an impediment to a rebound in domestic consumption. Also, it could lead to a plunge in asset prices and greater volatility of the financial market, likely undermining macro-prudentiality. As for private sector debt, it is recommendable to reinforce a support system for the financially disadvantaged and help companies enhance productivity and make more profits in order to facilitate recovery in household income to mitigate potential risks, rather than deliberately seeking debt reduction. Also necessary is to implement monetary policy instruments in harmony with relevant policy measures in that a monetary policy alone cannot resolve problems of financial imbalance intensified by rising housing prices and varying degrees of recovery by business type.

1) According to the Financial Stability Report released by the Bank of Korea (in June 2021), the private sector credit is estimated at 216.3% as a percent of GDP as of the end of the first quarter this year.

2) With regard to this, please refer to the Financial Stability Report published in June 2021 by the Bank of Korea.