Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Aligning the Capital Market with the 2050 Carbon Net Zero

Publication date Feb. 08, 2022

Summary

Although the Paris Agreement highlights the importance of climate finance, the growth of climate finance, improvements in capital market infrastructure, and financial firms’ preparation for carbon neutrality have yet to pick up speed. The financial sector could drive carbon neutrality of the industrial sector through net-zero portfolios by allocating financial resources. Thus, it could play a key role in managing and drawing the boundary between risks and opportunities arising from carbon neutrality. In particular, the capital market’s function of enhancing efficiencies in carbon emission reduction through climate finance has come to the fore. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate the long-standing, complex nature of climate risks into the valuation, performance assessment, and compensation systems to facilitate climate finance. Furthermore, it is desirable to reinforce regulatory supervision over capital market infrastructure such as taxonomy, evaluation scheme, methodologies, and evaluation agencies to ensure transparency and reliability of the capital market in the process of applying ESG factors that are qualitative indicators. Amid the global trend that the capital market is expanded into the carbon credit market, the carbon credit market is evolving into a place where spot and futures trading is implemented. Under the circumstances, the capital market could make up for the weakness of the ESG evaluation based on qualitative indicators by utilizing carbon price indicators, whereas the industrial sector could increase the predictability of carbon reduction costs and enable the more efficient selection of carbon reduction options. In this respect, Korea’s financial investment firms should consider committing to net-zero portfolios, as is the case with foreign financial firms, to ensure that such a shift in the carbon market contributes to carbon neutrality. They should no longer recognize the net-zero strategy as regulatory costs arising from carbon neutrality while preparing for a transition in asset allocation in line with the global asset market trend where added value is moving toward low-carbon sectors. In light of this, a paradigm shift is needed to perceive net zero as a capital market development strategy and investor protection measures to safeguard investors against greenwashing.

The role of the financial sector in determining the allocation of financial resources among industries is critical to carbon neutrality. Still, the financial sector is less active in solving the climate crisis than other industrial sectors. Under this context, this article tries to underscore the pivotal role that the financial sector and in particular, the capital market play in carbon neutrality, and to examine challenges for the capital market development to achieve carbon neutrality.

The importance of climate finance in the Paris Agreement

The financial sector is crucial to carbon neutrality in that it serves as the primary supplier of climate finance. Although it is not well known, the 2015 Paris Agreement text places great emphasis on the significance of climate finance. Article 2 of the Paris Agreement specifies that the treaty aims to ‘strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change’ and presents three intermediate targets as part of the effort to achieve the treaty’s objective,1) one of which is facilitating climate finance. In the economy, the financial sector acts as the main driver of carbon neutrality for other industrial sectors through various tools such as investment, lending, and capital contribution. In view of that, the Paris Agreement appears to recognize revitalization of the climate finance system as a key factor to reinforce the response to climate risks to ensure that such tools of the financial sector are effectively utilized to tackle climate change.

Considerable time has passed since the treaty entered into force and countries have announced their emission reduction targets. However, demand for climate finance falls far short of the level needed to reach carbon net zero by 2050. According to the CPI (2021),2) climate finance instruments were estimated to raise (invest) funds worth $632 billion globally in 2020. This figure is a 73% increase from $365 billion in 2014, but is far below the climate finance value required by the IEA (2021)3) for the 2050 carbon neutrality. The IEA predicts that the global climate finance value needed for energy transition would be $5 trillion on an annual basis by 2030 and $6 trillion from 2040 to 2050, assuming that the rise in global temperatures is limited to 1.5°C below pre-industrial levels. In arithmetical terms, the financial system including public finance should achieve more than an eight-fold increase in climate finance over a short term to reach net zero by 2050.

The significance of the capital market in climate finance

Climate finance-related challenges for carbon neutrality are not limited to expanding the volume of funds. What also matters is to identify an efficient climate finance instrument for carbon neutrality. The current climate finance statistics can give insight into this issue. Although the CPI does not classify sources of climate finance into banks and the capital market, it is possible to derive relevant estimates for each category from the CPI statistical data (2021).4) Out of $632 billion of the funds raised for climate finance in 2020, a total of $451 billion was financed from the capital market, for example, through direct equity, project-level equity, and market rate debt, accounting for 71% of the aggregate climate finance value. The rest is comprised of $34 billion of grants (5% of the total) and $147 billion (24% of the total) of a combination of direct debt in the form of loans and loans granted for the purpose of policy implementation (policy interest rate debt). As deals involving climate finance are associated with innovative investment areas such as decarbonization and renewables, a large portion of funds seem to have been financed from the capital market. It is notable that more than half of climate finance (51%) is sourced from public climate finance instruments. This means roughly half of climate finance has been supplied by public financial intuitions, regardless of whether capital is raised from the capital market or through loans. This situation reflects the difficulties of climate finance projects in attracting voluntary investments from the private sector, which explains why the Paris Agreement underscores public climate finance and pump-priming effects.

Concerning the critical role of the capital market in climate finance, a research project recently derived an intriguing finding that the funds raised from the capital market were more effective in cutting down CO2 emissions than the funds sourced from banks. ECB (2019a) and ECB (2019b)5) conducted an empirical analysis of 48 countries from the 1990s until lately to present that the development of the capital market (ratio of market capitalization to the combination of private credit and market capitalization) would contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions per capita. More specifically, the 1%p increase in the proportion of the capital market is expected to cut down per-capita carbon emissions by 0.024 metric tons. As mentioned above, this result is related to the innovation of climate finance projects. The capital market serves as a more efficient tool to raise funds for innovative projects. In practice, countries with an advanced capital market see a larger number of green patent applications.

After all, as pressure is mounting on the global economy to adopt carbon net zero initiatives and shift towards the low-carbon economy, the utilization of the capital market for climate finance is likely to come into focus. In terms of the financial system, the transition to the low-carbon economy would become a dynamic driver of accelerating the leading, balanced development of the capital market, going beyond the existing bank-centered system.

ESG-driven evolution in the capital market

In addition, climate finance will also require the capital market to execute a fundamental reform. Changes that climate finance would bring about to the capital market are associated with coordination among the features of climate change and the traditional capital market. But the two features seem to be quite disparate. As analyzed by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the threat of climate change entails both the transitional risk and the physical risk and can be characterized by complexity, long-term persistence, undiversifiable nature (especially in the case of the physical risk), whereas the traditional capital market is finance-based, diversifiable and short-term. The climate finance nature should be integrated into the existing capital market structure to achieve harmony between climate finance and the capital market, which could give rise to time discrepancy and changes in the valuation system.

Regulatory improvements in time discrepancy between climate finance with a long-term horizon and valuation of the short-term capital market are being underway with the introduction of the ESG approach. However, given that among ESG factors, climate risks have the longest-term horizon, there might be a great divergence between the existing valuation system and short-term investment performance assessment.6) It is desirable to integrate ESG factors into the valuation system and reflect such factors in the fiduciary duty of institutional investors. But it is necessary to consistently apply the ESG approach to the company-wide performance evaluation and compensation system to resolve time discrepancy, rather than narrowly recognizing ESG as an investment strategy. In particular, as regulations on climate risks come to the fore, net-zero portfolios are anticipated to serve as key constraints for optimization of financial firms. Under the circumstances, there would be a growing movement towards reflecting ESG factors in valuation, performance assessment, and compensation systems, which could alleviate the time discrepancy issues.

The biggest obstacle to the integration of ESG into the valuation system is transparency in assessment. The existing financial data-centered valuation is a transparent, objective, and independent system since all relevant factors are demonstrated through data. But ESG is a qualitative indicator. If not appropriately designed, the process of applying qualitative indicators to the valuation system to which transparency and objectivity are critical could undermine the transparency of the capital market, rather than making it more transparent. Furthermore, the valuation system incorporating climate risks is highly likely to transform the competition and industrial landscape by turning high-carbon sectors into stranded assets and adding value to green premiums of low-carbon sectors. In this respect, ESG integration would pose a big challenge for the capital market and thus, the role of a strict supervisor becomes more pivotal in the ESG-based valuation system, compared to in the financial data-centered valuation. Different levels of objectivity, expertise, and transparency in the valuation process and methodologies should be required, in addition to a different set of financial regulations on valuation agencies. In recent years, regulations on valuation infrastructure of the capital market have been beefed up, including regulatory supervision over Europe’s ESG indexes, registration of financial firms by ESG evaluators like MSCI, disclosure of valuation process and methodologies, green bond principles based on taxonomy, certification of green investing instruments, etc. Such tightened regulatory measures are recognized as a shift for accommodating ESG factors and enhancing transparency and reliability of the capital market.

The fundamental reform in the capital market has resulted in the emergence of the carbon credit market where the capital market is most actively engaged in climate finance. Carbon credits are intangible investment assets with property value. In foreign countries, their value and supply and demand are usually determined in association with the energy market. Price discovery hardly functions well within a small-scale trading market participated only by firms allocated with carbon credits. Given the existing structure where carbon credits are traded for future submission of credits, the market needs to evolve into a place that serves as both the spot and futures markets to properly implement a carbon price discovery mechanism. The carbon price for which efficiency is guaranteed through the spot and futures markets increases the predictability of carbon reduction costs, thereby enabling the establishment of the most efficient strategies to curtail carbon emissions at levels of the government or companies. Concerning climate finance, this mechanism could lead to the equitable carbon price and thus, facilitate qualitative indicators-based ESG evaluation, which positively affects transparency and reliability of the capital market.

The financial sector’s response: net-zero pledges

Although it is difficult to draw a comparison between nation-wide carbon neutrality and company-specific carbon neutrality in terms of goals, scope, strategies, etc., the two strategies must be complementary to each other. The company-specific carbon neutrality depends on the company’s willingness to adopt ESG management. In addition, the financial sector’s commitment to carbon neutrality serves as an important factor as it could drive the business sector’s carbon neutrality through allocation of financial resources. The Paris Agreement highlights the role and contribution of climate finance, and the public finance’s controllability regarding climate finance and the importance of public and private joint projects for climate finance should also be taken into account. Under this context, the efforts to leverage the financial sector to guide industrial sectors towards carbon neutrality would be gradually emphasized around the globe. To this end, specific measures should include the financial sector’s net-zero pledges and the systematization of green finance as an implementation strategy.

Net zero means that financial firms pledge to pursue carbon neutrality, which, unlike the nation-wide or company-specific carbon neutrality, aims to set an emission reduction target for asset portfolios built in the process of financial activities. This is in line with the Paris Agreement which stresses carbon neutrality and specifies that climate finance performs a unique function of reducing financial firms’ lending or investee firms’ carbon emissions (emissions beyond direct operations, scope 3). Considering this, financial firms actively engaged in climate finance need to declare their commitment to net-zero portfolios and come up with relevant roadmaps, action plans, and tools. In this process, green finance acts as a key instrument for implementation. In the financial sector, net-zero commitments made by financial investment businesses—equipped with a variety of tools including investment and divestment, exclusion and engagement with shareholders—would be increasingly underscored, in addition to the growing demand for climate finance through the capital market.

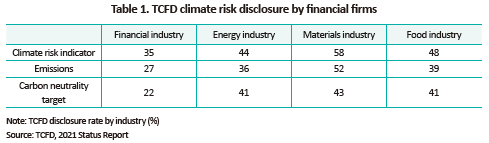

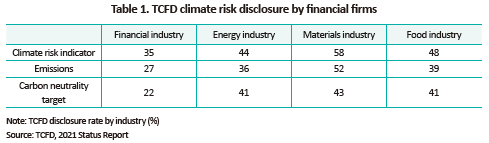

According to global statistics, financial firms’ net-zero pledges are spreading rapidly. As of 2020, a total of 1,069 financial firms with their assets worth $194 trillion (including commercial banks, asset management companies, pension funds) pledge support for the TCFD recommendations, the global framework that is regarded as a prelude to net-zero pledges and is evolving into the global regulatory system. However, climate risk disclosure rates (the ratio of financial firms implementing disclosures to financial firms pledging support) hardly indicate that the financial sector is more active in carbon neutrality than other industrial sectors. The disclosure rate of financial firms represents 28% as of 2020, lower than 36% for energy, 38% for materials, and 30% for food. Furthermore, disclosures of target figures closely related to net-zero pledges show that financial firms tend to be passive, compared to other sectors (see Table 1).

On a positive note, financial firms have accelerated the transition to net zero since the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, commonly referred to as COP26. The United Nations takes initiatives in promoting the trend that each financial sector including banks (including commercial banks), asset managers, and pension funds creates a global network to achieve carbon neutrality and jointly adopts the net-zero strategy. Banks have established the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) and pledged to build net-zero portfolios by 2050. Around the world, 98 banks taking up 43% ($66 trillion) of the total global banking assets have joined the NZBA and are preparing for net-zero pledges, including Korea’s four banks (Industrial Bank of Korea, Jeonbuk Bank, Shinhan Bank, KB Kookmin Bank) as well as Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America. Among the members, KB Kookmin Bank pledged to support net-zero initiatives in 2021. Asset holders including pension funds have formed the Net-Zero Asset Owners Alliance (NZAOA). Pension funds recognize net zero as part of the fiduciary duty and intend to accomplish net-zero portfolios by 2050. The NZAOA is participated by 43 global asset holders including CalPERS, Australia’s pension fund CBUS, and other pension funds. Asset management companies have founded the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (NGAM) that aims to build net-zero portfolios by 2050. As initial members of NGAM, 43 asset managers with $ 11.9 trillion in AUM have promised to achieve net-zero portfolios that represent 35% of their entire portfolios by 2035.

Implications for Korea’s financial investment services

In Korea, financial investment firms have remained passive in adopting the net-zero strategy. According to the survey on Korea’s top 100 financial institutions by Solutions for Our Climate (2022),7) five asset managers and two securities firms have committed to net-zero portfolios while no pension fund has made such a commitment. On the other hand, commercial banks affiliated with financial holding companies are actively engaged in net-zero commitments, four of which have recently pledged net-zero targets certified by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Furthermore, financial investment firms rarely show strong support for the TCFD recommendations that are deemed a preparation phase to net-zero pledges. As of January 2022, 49 financial institutions pledge their support for TCFD, which include 17 asset management companies taking up the largest proportion, 12 banks, two securities firms, and one pension fund. This indicates that banks in affiliation with financial holding companies are the most active players in terms of net-zero commitments. It is noteworthy that the capital market is expected to play an active role in climate finance in the current low-carbon economic trend, and that financial investment firms have various tools to implement net zero, such as investment, exclusion, divestment, engagement with shareholders, and exercise of voting rights. Considering this, Korea’s financial investment firms need to be more proactive in building net-zero portfolios. They should no longer recognize the net-zero strategy as regulatory costs arising from carbon neutrality while preparing for a transition in asset allocation in line with the global asset market trend where added value is moving toward low-carbon sectors. In light of this, a paradigm shift is needed to perceive net zero as a capital market development strategy and investor protection measures to safeguard investors against greenwashing.

1) The first target is preventing the global temperatures from further rising, the second target is participation in climate change adaptation to avoid a climate disaster and the third target is making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

2) CPI, 2021, Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021

3) IEA, 2021, Net Zero by 2050: A roadmap for the global energy system

4) According to the UNFCCC’s classification, climate finance aims to raise funds to cut down greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the adverse impact of greenhouse gas, and the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) classifies climate finance into grants, project-level debt, project-level equity, direct debt, and direct equity.

5) ECB, 2019a, Finance and decarbonization: why equity markets do it better

ECB, 2019b Finance and carbon emissions

6) According to the World Bank data, the average stock holding period is 9 months for Korea, 11 months for the US, 18 months for Germany, and 21 months for Canada.

7) Solutions for Our Climate, 2022, Evaluation of climate policies adopted by Korea’s 100 major financial institutions.

The importance of climate finance in the Paris Agreement

The financial sector is crucial to carbon neutrality in that it serves as the primary supplier of climate finance. Although it is not well known, the 2015 Paris Agreement text places great emphasis on the significance of climate finance. Article 2 of the Paris Agreement specifies that the treaty aims to ‘strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change’ and presents three intermediate targets as part of the effort to achieve the treaty’s objective,1) one of which is facilitating climate finance. In the economy, the financial sector acts as the main driver of carbon neutrality for other industrial sectors through various tools such as investment, lending, and capital contribution. In view of that, the Paris Agreement appears to recognize revitalization of the climate finance system as a key factor to reinforce the response to climate risks to ensure that such tools of the financial sector are effectively utilized to tackle climate change.

Considerable time has passed since the treaty entered into force and countries have announced their emission reduction targets. However, demand for climate finance falls far short of the level needed to reach carbon net zero by 2050. According to the CPI (2021),2) climate finance instruments were estimated to raise (invest) funds worth $632 billion globally in 2020. This figure is a 73% increase from $365 billion in 2014, but is far below the climate finance value required by the IEA (2021)3) for the 2050 carbon neutrality. The IEA predicts that the global climate finance value needed for energy transition would be $5 trillion on an annual basis by 2030 and $6 trillion from 2040 to 2050, assuming that the rise in global temperatures is limited to 1.5°C below pre-industrial levels. In arithmetical terms, the financial system including public finance should achieve more than an eight-fold increase in climate finance over a short term to reach net zero by 2050.

The significance of the capital market in climate finance

Climate finance-related challenges for carbon neutrality are not limited to expanding the volume of funds. What also matters is to identify an efficient climate finance instrument for carbon neutrality. The current climate finance statistics can give insight into this issue. Although the CPI does not classify sources of climate finance into banks and the capital market, it is possible to derive relevant estimates for each category from the CPI statistical data (2021).4) Out of $632 billion of the funds raised for climate finance in 2020, a total of $451 billion was financed from the capital market, for example, through direct equity, project-level equity, and market rate debt, accounting for 71% of the aggregate climate finance value. The rest is comprised of $34 billion of grants (5% of the total) and $147 billion (24% of the total) of a combination of direct debt in the form of loans and loans granted for the purpose of policy implementation (policy interest rate debt). As deals involving climate finance are associated with innovative investment areas such as decarbonization and renewables, a large portion of funds seem to have been financed from the capital market. It is notable that more than half of climate finance (51%) is sourced from public climate finance instruments. This means roughly half of climate finance has been supplied by public financial intuitions, regardless of whether capital is raised from the capital market or through loans. This situation reflects the difficulties of climate finance projects in attracting voluntary investments from the private sector, which explains why the Paris Agreement underscores public climate finance and pump-priming effects.

Concerning the critical role of the capital market in climate finance, a research project recently derived an intriguing finding that the funds raised from the capital market were more effective in cutting down CO2 emissions than the funds sourced from banks. ECB (2019a) and ECB (2019b)5) conducted an empirical analysis of 48 countries from the 1990s until lately to present that the development of the capital market (ratio of market capitalization to the combination of private credit and market capitalization) would contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions per capita. More specifically, the 1%p increase in the proportion of the capital market is expected to cut down per-capita carbon emissions by 0.024 metric tons. As mentioned above, this result is related to the innovation of climate finance projects. The capital market serves as a more efficient tool to raise funds for innovative projects. In practice, countries with an advanced capital market see a larger number of green patent applications.

After all, as pressure is mounting on the global economy to adopt carbon net zero initiatives and shift towards the low-carbon economy, the utilization of the capital market for climate finance is likely to come into focus. In terms of the financial system, the transition to the low-carbon economy would become a dynamic driver of accelerating the leading, balanced development of the capital market, going beyond the existing bank-centered system.

ESG-driven evolution in the capital market

In addition, climate finance will also require the capital market to execute a fundamental reform. Changes that climate finance would bring about to the capital market are associated with coordination among the features of climate change and the traditional capital market. But the two features seem to be quite disparate. As analyzed by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the threat of climate change entails both the transitional risk and the physical risk and can be characterized by complexity, long-term persistence, undiversifiable nature (especially in the case of the physical risk), whereas the traditional capital market is finance-based, diversifiable and short-term. The climate finance nature should be integrated into the existing capital market structure to achieve harmony between climate finance and the capital market, which could give rise to time discrepancy and changes in the valuation system.

Regulatory improvements in time discrepancy between climate finance with a long-term horizon and valuation of the short-term capital market are being underway with the introduction of the ESG approach. However, given that among ESG factors, climate risks have the longest-term horizon, there might be a great divergence between the existing valuation system and short-term investment performance assessment.6) It is desirable to integrate ESG factors into the valuation system and reflect such factors in the fiduciary duty of institutional investors. But it is necessary to consistently apply the ESG approach to the company-wide performance evaluation and compensation system to resolve time discrepancy, rather than narrowly recognizing ESG as an investment strategy. In particular, as regulations on climate risks come to the fore, net-zero portfolios are anticipated to serve as key constraints for optimization of financial firms. Under the circumstances, there would be a growing movement towards reflecting ESG factors in valuation, performance assessment, and compensation systems, which could alleviate the time discrepancy issues.

The biggest obstacle to the integration of ESG into the valuation system is transparency in assessment. The existing financial data-centered valuation is a transparent, objective, and independent system since all relevant factors are demonstrated through data. But ESG is a qualitative indicator. If not appropriately designed, the process of applying qualitative indicators to the valuation system to which transparency and objectivity are critical could undermine the transparency of the capital market, rather than making it more transparent. Furthermore, the valuation system incorporating climate risks is highly likely to transform the competition and industrial landscape by turning high-carbon sectors into stranded assets and adding value to green premiums of low-carbon sectors. In this respect, ESG integration would pose a big challenge for the capital market and thus, the role of a strict supervisor becomes more pivotal in the ESG-based valuation system, compared to in the financial data-centered valuation. Different levels of objectivity, expertise, and transparency in the valuation process and methodologies should be required, in addition to a different set of financial regulations on valuation agencies. In recent years, regulations on valuation infrastructure of the capital market have been beefed up, including regulatory supervision over Europe’s ESG indexes, registration of financial firms by ESG evaluators like MSCI, disclosure of valuation process and methodologies, green bond principles based on taxonomy, certification of green investing instruments, etc. Such tightened regulatory measures are recognized as a shift for accommodating ESG factors and enhancing transparency and reliability of the capital market.

The fundamental reform in the capital market has resulted in the emergence of the carbon credit market where the capital market is most actively engaged in climate finance. Carbon credits are intangible investment assets with property value. In foreign countries, their value and supply and demand are usually determined in association with the energy market. Price discovery hardly functions well within a small-scale trading market participated only by firms allocated with carbon credits. Given the existing structure where carbon credits are traded for future submission of credits, the market needs to evolve into a place that serves as both the spot and futures markets to properly implement a carbon price discovery mechanism. The carbon price for which efficiency is guaranteed through the spot and futures markets increases the predictability of carbon reduction costs, thereby enabling the establishment of the most efficient strategies to curtail carbon emissions at levels of the government or companies. Concerning climate finance, this mechanism could lead to the equitable carbon price and thus, facilitate qualitative indicators-based ESG evaluation, which positively affects transparency and reliability of the capital market.

The financial sector’s response: net-zero pledges

Although it is difficult to draw a comparison between nation-wide carbon neutrality and company-specific carbon neutrality in terms of goals, scope, strategies, etc., the two strategies must be complementary to each other. The company-specific carbon neutrality depends on the company’s willingness to adopt ESG management. In addition, the financial sector’s commitment to carbon neutrality serves as an important factor as it could drive the business sector’s carbon neutrality through allocation of financial resources. The Paris Agreement highlights the role and contribution of climate finance, and the public finance’s controllability regarding climate finance and the importance of public and private joint projects for climate finance should also be taken into account. Under this context, the efforts to leverage the financial sector to guide industrial sectors towards carbon neutrality would be gradually emphasized around the globe. To this end, specific measures should include the financial sector’s net-zero pledges and the systematization of green finance as an implementation strategy.

Net zero means that financial firms pledge to pursue carbon neutrality, which, unlike the nation-wide or company-specific carbon neutrality, aims to set an emission reduction target for asset portfolios built in the process of financial activities. This is in line with the Paris Agreement which stresses carbon neutrality and specifies that climate finance performs a unique function of reducing financial firms’ lending or investee firms’ carbon emissions (emissions beyond direct operations, scope 3). Considering this, financial firms actively engaged in climate finance need to declare their commitment to net-zero portfolios and come up with relevant roadmaps, action plans, and tools. In this process, green finance acts as a key instrument for implementation. In the financial sector, net-zero commitments made by financial investment businesses—equipped with a variety of tools including investment and divestment, exclusion and engagement with shareholders—would be increasingly underscored, in addition to the growing demand for climate finance through the capital market.

According to global statistics, financial firms’ net-zero pledges are spreading rapidly. As of 2020, a total of 1,069 financial firms with their assets worth $194 trillion (including commercial banks, asset management companies, pension funds) pledge support for the TCFD recommendations, the global framework that is regarded as a prelude to net-zero pledges and is evolving into the global regulatory system. However, climate risk disclosure rates (the ratio of financial firms implementing disclosures to financial firms pledging support) hardly indicate that the financial sector is more active in carbon neutrality than other industrial sectors. The disclosure rate of financial firms represents 28% as of 2020, lower than 36% for energy, 38% for materials, and 30% for food. Furthermore, disclosures of target figures closely related to net-zero pledges show that financial firms tend to be passive, compared to other sectors (see Table 1).

Implications for Korea’s financial investment services

In Korea, financial investment firms have remained passive in adopting the net-zero strategy. According to the survey on Korea’s top 100 financial institutions by Solutions for Our Climate (2022),7) five asset managers and two securities firms have committed to net-zero portfolios while no pension fund has made such a commitment. On the other hand, commercial banks affiliated with financial holding companies are actively engaged in net-zero commitments, four of which have recently pledged net-zero targets certified by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Furthermore, financial investment firms rarely show strong support for the TCFD recommendations that are deemed a preparation phase to net-zero pledges. As of January 2022, 49 financial institutions pledge their support for TCFD, which include 17 asset management companies taking up the largest proportion, 12 banks, two securities firms, and one pension fund. This indicates that banks in affiliation with financial holding companies are the most active players in terms of net-zero commitments. It is noteworthy that the capital market is expected to play an active role in climate finance in the current low-carbon economic trend, and that financial investment firms have various tools to implement net zero, such as investment, exclusion, divestment, engagement with shareholders, and exercise of voting rights. Considering this, Korea’s financial investment firms need to be more proactive in building net-zero portfolios. They should no longer recognize the net-zero strategy as regulatory costs arising from carbon neutrality while preparing for a transition in asset allocation in line with the global asset market trend where added value is moving toward low-carbon sectors. In light of this, a paradigm shift is needed to perceive net zero as a capital market development strategy and investor protection measures to safeguard investors against greenwashing.

1) The first target is preventing the global temperatures from further rising, the second target is participation in climate change adaptation to avoid a climate disaster and the third target is making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

2) CPI, 2021, Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021

3) IEA, 2021, Net Zero by 2050: A roadmap for the global energy system

4) According to the UNFCCC’s classification, climate finance aims to raise funds to cut down greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the adverse impact of greenhouse gas, and the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) classifies climate finance into grants, project-level debt, project-level equity, direct debt, and direct equity.

5) ECB, 2019a, Finance and decarbonization: why equity markets do it better

ECB, 2019b Finance and carbon emissions

6) According to the World Bank data, the average stock holding period is 9 months for Korea, 11 months for the US, 18 months for Germany, and 21 months for Canada.

7) Solutions for Our Climate, 2022, Evaluation of climate policies adopted by Korea’s 100 major financial institutions.