Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Financial Market Stabilization Facilities of Korea and the US: Differences and Policy Implications

Publication date Nov. 08, 2022

Summary

Amid ongoing rate hikes, the financial markets at home and abroad are suffering great fluctuations. The liquidity of financial firms has been aggravated drastically, and credit spreads have increased to an unusual level. While the corporate bond market faces severe strains, the foreign exchange rate continues a sharp upward trend. These worrying developments necessitate the implementation of financial market stabilization facilities once again.

In the process of overcoming the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, the financial markets of Korea and the US have accumulated experience in how to operate financial market stabilization facilities. A comparative analysis of the facilities adopted by the two countries reveals the following differences.

① Korea is highly dependent on private financial companies to secure funding for stabilization facilities, while the US uses the Fed’s monetary power.

② The US fiscal authorities (the Department of the Treasury) take over credit risk arising from the operation of financial market stabilization facilities, whereas credit risk could be shared by private financial companies contributing to such facilities in Korea.

③ The Fed’s policy tools are segmented by markets and the intervention in the CP market is implemented for the first step. Compared with the US, Korea rarely operates different stabilization programs for each segmented market and has yet to fully recognize the urgency of the short-term money market.

④ The US reflects the costs of liquidity support in pricing by adding pricing fees, while Korea hardly requires such fees as its policy puts more weight on support for companies.

⑤ US financial market stabilization facilities hardly intervene in the stock market but such intervention can be observed in Korea.

The need for financial market stabilization facilities is growing once again. If the possibility that financial firms or private companies go bankrupt increases sharply amid strong signs of a market crisis, financial market stabilization measures should be executed immediately on a massive scale. As such facilities serve as a safeguard against a financial emergency, their execution method and process should be thoroughly examined and manualized before any crisis occurs. The readiness with well-functioning emergency manual could make a huge difference between life and death for companies in the financial crisis period.

In the process of overcoming the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, the financial markets of Korea and the US have accumulated experience in how to operate financial market stabilization facilities. A comparative analysis of the facilities adopted by the two countries reveals the following differences.

① Korea is highly dependent on private financial companies to secure funding for stabilization facilities, while the US uses the Fed’s monetary power.

② The US fiscal authorities (the Department of the Treasury) take over credit risk arising from the operation of financial market stabilization facilities, whereas credit risk could be shared by private financial companies contributing to such facilities in Korea.

③ The Fed’s policy tools are segmented by markets and the intervention in the CP market is implemented for the first step. Compared with the US, Korea rarely operates different stabilization programs for each segmented market and has yet to fully recognize the urgency of the short-term money market.

④ The US reflects the costs of liquidity support in pricing by adding pricing fees, while Korea hardly requires such fees as its policy puts more weight on support for companies.

⑤ US financial market stabilization facilities hardly intervene in the stock market but such intervention can be observed in Korea.

The need for financial market stabilization facilities is growing once again. If the possibility that financial firms or private companies go bankrupt increases sharply amid strong signs of a market crisis, financial market stabilization measures should be executed immediately on a massive scale. As such facilities serve as a safeguard against a financial emergency, their execution method and process should be thoroughly examined and manualized before any crisis occurs. The readiness with well-functioning emergency manual could make a huge difference between life and death for companies in the financial crisis period.

Amid ongoing rate hikes by the US Fed, the financial markets at home and abroad are suffering great fluctuations. The Fed’s base interest rate that ranged from 0% to 0.25% in January 2022 has jumped to 3% to 3.25% as of October 2022, which will definitely increase to 3.75% to 4.0% in November and is expected to climb further to 4.5% to 4.75% by the end of this year. Bank of Korea (BoK) is also accelerating the increase in its key interest rates to keep pace with the Fed’s rate hikes. The central bank has continuously raised base rates at each meeting of the Monetary Policy Board since April 2022 and is anticipated to drive up the key interest rate to around 3.5%.

Abrupt rate increases by both the Fed and BoK have sent shock waves through the global financial market and Korea’s domestic market. The decline in stock prices has continued throughout the year, and the bond market has seen bond yields showing a sharp upward trend. The KOSPI has dropped to 2,218.09 points as of October 20, 2022, down 770.68 (25.79%) compared to the beginning of the year (2,988.77), while the KOSDAQ suffered a 34.44% decline to 680.44 from 1,037.83 during the same period. As the US dollar has gained strength prominently in the foreign exchange market, the won-dollar exchange rate has soared 20.26% (KRW 241.5) to KRW 1,433.30 as of October 20 from the beginning of the year (KRW 1,191.8). Yields on bonds continue to rise and credit spreads have increased to an unusual level. The yield on Korea Treasury Bonds (KTBs) that traded at 1.855% earlier this year has been pushed up to 4.350% as of October 20. In addition, the credit spread (between the 3-year corporate bond (AA-) and the 3-year KTB) has gone up to 123.8bp from 60.5bp earlier in the year.

The rise in interest rates, the fall in share prices and the depreciation of the won have exacerbated market jitters. A liquid crunch observed in the bond market and the FX market could have a significant impact on corporate financing activities, which requires extra caution. The dollar’s strength against the won adversely affects the trade balance—one of the pillars of Korea’s economy—and boosts import prices, thereby adding fuel to the skyrocketing domestic inflation. The shortage of funds in the bond market drives up market interest rates while also widening credit spreads. With a sharp upward trend of interest rates for more than six months, the fear of the market has spread out of control. Some even raise concerns that if this continues well into next year, Minsky Moment that all market participants dread could take place.

If the panic felt by market participants overwhelms reasonable decision making, the market is likely to see a race to disposal of assets, which could lead to the growth of non-performing assets and rising costs. At a time of economic turmoil, the role of financial market stabilization facilities would come to the fore. Government intervention through such stabilization facilities would be justifiable to avoid the market collapse driven by panic selling and ensure even partial operation of market functions. This intervention could stabilize the market, contributing to enhancing the welfare of economic players. In this respect, the Korean government’s plan for providing liquidity to corporate bond and short-term money markets is expected to have positive and significant effects on the recovery of market functions.

Against this backdrop, this article intends to present types of financial market stabilization facilities that could be used to address the shortage of funds, and to explore how to utilize them to prepare for a potential large-scale credit event. For your reference, this article was prepared before relevant government measures were released on October 23 and aims to analyze universal characteristics required for financial market stabilization facilities, rather than conducting an ex-post assessment of the October 23 measures.

Types and characteristics of Korea’s financial market stabilization facilities: The Covid-19 pandemic era

As for various financial market stabilization facilities adopted by the Korean government, the bond market stabilization fund (BMSF), P-CBOs, the quick bond takeover program, and the stock market stabilization fund (SMSF) are commonly used. Among them, the BMSF, P-CBOs, and the quick bond takeover program could improve poor capital circulation through the market by fixing blockages in capital flow when corporate funding is impeded by market strains, thereby reducing the risk of corporate insolvency. Accordingly, they seem to be more effective mechanisms in providing financial support for companies. Considering its primary goal of boosting stock prices, the SMSF may only have a marginal effect on revitalizing capital inflow.

In the midst of the domestic financial market turmoil triggered by the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s fiscal authorities unveiled the aforementioned stabilization measures to normalize financial market functions.1) The BMSF has been established to provide liquidity to companies suffering a temporary lack of funds due to strains in the bond market and to prevent credit spreads from widening excessively. The government decided to add KRW 10 trillion to the existing BMSF of KRW 10 trillion—established during the 2008 global financial crisis—to alleviate the Covid 19-induced liquidity crunch in the bond market and provide liquidity to financially strapped companies. A total of 84 financial institutions including banks, securities firms, insurance firms, and government-sponsored financial institutions have contributed to creating the fund. Its investment targets include corporate bonds, CP of blue-chip companies, asset-backed short-term bonds, and financial bonds. The BMSF establishment plan and its operational details were announced on March 19, and March 24, 2022, respectively. After the first capital call for KRW 3 trillion, it commenced purchasing corporate bonds on April 2, 2022.

P-CBOs aim to stabilize the corporate bond market and support corporate financing. As the name suggests, they are designed to take over corporate bonds in the bond issuance market and securitize them in the form of collateralized bond obligations (CBOs). P-CBOs were issued in the total amount of KRW 6.7 trillion (KRW 5 trillion added to the first issuance of KRW 1.7 trillion) to support the issuance of corporate bonds for medium-sized enterprises and large companies that suffered Covid 19-induced liquidity shortages. As the first step of P-CBO issuance, the Korea Development Bank, Korea’s policy bank, takes over corporate bonds for sale to main creditor banks and the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund. And then P-CBOs are issued after credit reinforcement is conducted by the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund.

The quick bond takeover program is designed to support companies (SMEs and large companies) that wrestle with corporate bond redemption as their bonds come to maturity around the same time. Under the program, the Korea Development Bank will take over 80 percent of corporate bonds issued by such troubled companies. Upon the maturity of bonds, companies redeem 20 percent of the bonds while the Korea Development Bank rolls over the remaining 80 percent. Through credit reinforcement by the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund, most corporate bonds taken over by the Korea Development Bank (80 percent of issued bonds) are disposed of in the market in the form of P-CBOs while some are sold to creditor banks to diversify credit risks. With the 2020 quick bond takeover program, a net amount of KRW 2.2 trillion was injected into companies.

The SMSF has been created through contributions by various financial institutions to serve as a buffer zone in the stock market, for the purpose of alleviating a dramatic stock price slump and excessive market volatility. This fund should be in principle managed temporarily until the stock market rebounds and its investment only targets representative market indexes not to affect the prices of individual stocks. Like the BMSF, it secures funding through capital calls and invests in representative indexes of the stock market (ex, KOSPI200). As for financial institutions investing in the fund, their contributions could be subject to a relaxed capital adequacy ratio (risk weight). During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, five financial holding companies, 18 leading financial firms in banking, insurance and securities sectors and securities institutions (Korea Exchange, Korea Securities Depository, Korea Financial Investment Association) contributed a total of KRW 10.7 trillion to the fund, which, however, was not put to use because the stock market rallied swiftly. The SMSF can be distinguished from other stabilization tools in that it plays a minor role in providing funds to companies, despite its impact of mitigating a decline in stock prices.

Types and characteristics of US financial market stabilization facilities

Financial market stabilization facilities that the Fed operates in consultation with the US government at a time of financial or economic crises can be roughly categorized into the liquidity provision program, the capital market products purchase program and the loan support program. To compare with Korea’s stabilization mechanisms, this article analyzes key features of capital market products purchase programs utilized by the US, especially including the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) for CP purchases, the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) for corporate bond purchases, and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) for supporting the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS). The prominent feature commonly observed in those programs is role division and cooperative system between the Fed and the US government. In other words, the Fed is responsible for funding and the government (the Department of the Treasury) assumes the credit risk posed by the operation of such facilities. Generally, financial market stabilization facilities play a role in stabilizing the mentality of market participants to ensure that market functions well in a crisis. To this end, emergency funds large enough to quell market jitters should be provided swiftly. As most financial institutions are highly likely to face a liquidity squeeze during a crisis, funding from financial institutions’ contributions cannot be implemented expeditiously and has limitations in securing sufficient funds. To solve this problem, the Fed has decided to mobilize its monetary power, rather than obligating private financial firms to pay contributions into those facilities.

After funding is secured, credit risk comes to the fore during the process of operating facilities. When purchasing corporate bonds or CP with inherent risks, financial market stabilization facilities might face a default on such bonds. The facilities try to minimize the possibility of any credit event by setting criteria for bonds or CP eligible for purchase but it is impossible to eliminate the possibility of a default. In the US, any risk posed by default on products purchased by stabilization programs is borne by the Treasury while the Fed is separated from credit risk. This mechanism is based on the principle that the Fed responsible for establishing the nation’s monetary policy can cooperate in funding but it should not act as a final authority that assumes credit risk arising therefrom. This means such credit risk should be taken on by the authorities in charge of financial industry policies. According to the principle, the US Treasury implements equity tranche investments in the facilities by using the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) to insulate the Fed’s funding from a potential default.

The CPFF and TALF were established during the 2008 global financial crisis. After the collapse of Lehman Brothers caused strains in the CP market, the Fed set up the first CPFF (2008) on October 27, 2008 through cooperation with the Treasury in a bid to urgently provide liquidity to the short-term money market. The CPFF was operated under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury made equity investments in the CPFF through the ESF. The CPFF set the criteria for CP eligible for purchase (eligible CP) and bought ordinary CP and ABCP by strictly complying with the criteria. To meet the criteria, CP should receive a rating of A-1/P-1/F1 or higher from major credit rating agencies. The facility fees were calculated as 10bp of the CPFF’s maximum balance amount, and the pricing was based on the 3-month Overnight Index Swap (OIS) +110bp. The Fed granted loans to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) created for CP purchases and the SPV bought eligible CP from registered PDs under the supervision of the New York Fed. After being established in 2008, the CPFF bought eligible CP until February 1, 2010 and came to an end with all CP reaching maturity on April 26, 2010. As no default event occurred for any CP purchased during that period, all of them were redeemed at maturity. As strains rose again in the short-term money market amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed started a new CPFF program (2020) on March 17, 2020. With the same structure as the CPFF (2008)’s, the CPFF (2020) bought CP until March 31, 2021, none of which fell into default.

The TALF is designed to meet the credit needs of households and small businesses. When households and small businesses suffered a severe credit crunch upon the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the Fed established the TALF (2008)—the support program for households and small businesses using asset-backed securities as collateral—in consultation with the Treasury Department on November 25, 2008. As is the case with the CPFF, the TALF was operated under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury made equity investments in the TALF through the ESF. The collateral eligible for asset-backed securities (ABS) under the TALF is limited to student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA). The same facility fees of 10bp as the CPFF’s were charged, and the pricing was based on 30-day Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) +150bp for CLOs, Federal Fund Rate +75bp for the SBA-guaranteed loans, and 2-year OIS +125bp for collateral of other ABS. The TALF (2008) started providing funds to the ABS market in March 2009 and ended on June 30, 2010. A new TALF program (2020) was created on March 23, 2020 and stopped making new loans as of December 31, 2020.

The PMCCF and SMCCF were established in 2020 to provide liquidity to the corporate bond market. They did not exist during the 2008 global financial crisis but the Fed created these facilities on March 23, 2020 through cooperation with the Treasury Department, with the aim of easing strains in the corporate bond market. As their names suggest, the PMCCF is a program designed to purchase corporate bonds in the primary market while the SMCCF aims to buy corporate bonds in the secondary market. As with the TALF and CPFF, the PMCCF and SMCCF were managed under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury, using the ESF, made equity investments in the facilities. Corporate bonds that the PMCCF could purchase should have a credit rating of BBB-/Baa3 or higher as of March 22, 2020. To be eligible for the PMCCF, a company that met the requirement prior to March 22 but failed to maintain the required credit rating thereafter should be rated BB-/Ba3 or higher at least. The credit rating requirement equally applied to the SMCCF. As for the PMCCF, pricing would vary by issuing companies depending on market conditions and eligible issuers have to pay facility fees of 100bp. On the other hand, the SMCCF does not charge any extra facility fees and purchases corporate bonds at a fair market price because if the secondary market charges additional facility fees, corporate bond holders are not incentivized to sell their bond holdings to the SMCCF. The PMCCF and SMCCF ceased purchasing corporate bonds on December 31, 2020.

Financial market stabilization facilities: Comparison and policy implications

A comparative analysis of stabilization mechanisms adopted by the US and Korea reveals the following differences. First, Korea is highly dependent on private financial institutions to secure funding for stabilization facilities, while the US uses the Fed’s monetary power. Although some criticize the use of the Fed’s monetary power, it is worth noting its advantages including swift funding and availability of large-scale, long-term funding. Raising funds from private financial institutions requires a multilateral agreement on the allocation of contributions and procedures for consent. Accordingly, funding through a central bank is more beneficial given that speed is of great importance in financial or economic turmoil. Furthermore, contributions made by the private sector have limitations in expanding the funding amount above a certain level and if a crisis prolongs, the effect of such a funding method would be limited.

Second, credit risk arising from the operation of stabilization facilities is assumed by the US fiscal authorities (the Treasury Department), whereas credit risk in Korea could be shared by private financial institutions contributing to such facilities. If the government bears credit risk, this could trigger a controversy over moral hazards. Amid a financial or economic crisis, however, it is necessary to put priority on the normal operation of market functions, rather than concerns about potential moral hazards. This implies risk-taking activities by the government can be justifiable at times of crisis, which the Korean government needs to consider when operating relevant mechanisms.

Third, financial market stabilization programs of the US are segmented by market and among them, the intervention in the short-term money market is implemented for the first step. Compared with the US, Korea is less likely to operate different programs for each market and has yet to fully recognize the urgency of the short-term money market. As stated above, financial market stabilization facilities of the US—each specializing in the CP market, primary market, secondary market and ABS market—could be laser-focused on respective problems. As shown in the 2008 and 2020 cases, the intervention in the CP market should be first implemented to provide funds to companies, to be followed by measures targeting the corporate bonds and ABS markets. In contrast, Korea has drawn no clear distinction between the corporate bond market and the short-term money market comprised of CP and short-term electronic bonds. Accordingly, both corporate bonds and CP are purchased by Korea’s BMSF. P-CBOs are structured to support the ABS market but in terms of economic substance, it acts more like a support program for the corporate bond market. On top of that, Korea is less aware of the need for government intervention in the short-term money market, compared with the US.

Fourth, stabilization programs of the US reflect the costs of liquidity support in pricing by adding pricing fees, while Korea’s programs rarely require pricing fees as its policy focuses on support for companies or investors. As shown in the US cases, the CPFF, TALF and PMCCF charge pricing fees of 110bp, 75bp-150bp and 100bp, respectively. The SMCCF is the only facility not adding pricing fees. Aside from the SMCCF, the level of pricing fees is considerably high, which suggests that such support programs are not equivalent to government subsidization. This stems from the philosophy that beneficiaries of stabilization programs ought to bear the cost of relevant financial support. This is in stark contrast to Korea’s stabilization programs that generally tend to apply market interest rates or lower to pricing. Such a mechanism is underpinned by the perception that demanding financially strapped companies to pay the cost of such benefits is too harsh and that it is necessary to support their survival by providing benefits. Concerns have been raised that without pricing fees, emergency fund support by financial market stabilization facilities could encourage moral hazards. When it comes to the operation of stabilization programs, it seems reasonable for beneficiaries of liquidity support to bear a certain level of costs.

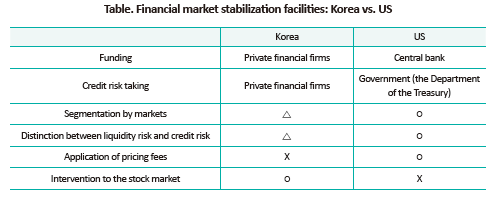

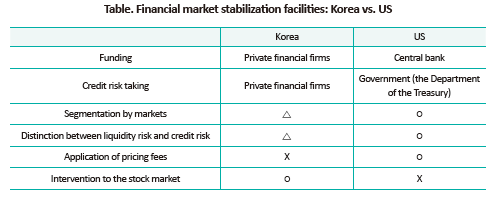

Lastly, although stabilization programs of the US hardly intervene in the stock market, such intervention can be observed in Korea. Various facilities run by the Fed usually function within the realm of debt instrument-based fund transactions, none of which, however, backs capital flow into the stock market. The comparative analysis results are summed up in the following table.

When financial market conditions deteriorate severely, the government should implement market stabilization measures rapidly and resolutely. If the possibility that financial firms or private companies go bankrupt increases sharply amid strong signs of market risk, financial market stabilization measures should be executed immediately on a massive scale. Soaring market interest rates are aggravating the financial market environment of Korea. The need for stabilization facilities is growing once again following the March 2020 Covid-19 crisis. In this respect, the government measures for providing liquidity to the market announced on October 23 are deemed a swift and proper response to deal with those worrying developments. Considering the potential recurrence of a liquidity squeeze, the government should work on additional countermeasures proactively.

As financial market stabilization facilities serve as a safeguard against a financial crisis, their execution method and process should be thoroughly examined and manualized before any crisis occurs. A manual for how to operate such facilities could make a huge difference between life and death for every company faced with a financial crisis. Even after being put into action several times, Korea’s stabilization programs have not been fully manualized in terms of funding methods and risk taking, which requires aggressive efforts to improve the current financial market stabilization regime.

1) Financial Services Commission, March 19, 2020, Covid-19 package programs for public welfare and financial stability, press release.

Financial Services Commission, March 24, 2020, Covid-19 financial market stabilization measures, press release.

Financial Services Commission, March 27, 2020, The government will implement package programs of KRW 100 trillion or more for supporting public welfare and financial stability, together with 14 related financial institutions, press release.

Abrupt rate increases by both the Fed and BoK have sent shock waves through the global financial market and Korea’s domestic market. The decline in stock prices has continued throughout the year, and the bond market has seen bond yields showing a sharp upward trend. The KOSPI has dropped to 2,218.09 points as of October 20, 2022, down 770.68 (25.79%) compared to the beginning of the year (2,988.77), while the KOSDAQ suffered a 34.44% decline to 680.44 from 1,037.83 during the same period. As the US dollar has gained strength prominently in the foreign exchange market, the won-dollar exchange rate has soared 20.26% (KRW 241.5) to KRW 1,433.30 as of October 20 from the beginning of the year (KRW 1,191.8). Yields on bonds continue to rise and credit spreads have increased to an unusual level. The yield on Korea Treasury Bonds (KTBs) that traded at 1.855% earlier this year has been pushed up to 4.350% as of October 20. In addition, the credit spread (between the 3-year corporate bond (AA-) and the 3-year KTB) has gone up to 123.8bp from 60.5bp earlier in the year.

The rise in interest rates, the fall in share prices and the depreciation of the won have exacerbated market jitters. A liquid crunch observed in the bond market and the FX market could have a significant impact on corporate financing activities, which requires extra caution. The dollar’s strength against the won adversely affects the trade balance—one of the pillars of Korea’s economy—and boosts import prices, thereby adding fuel to the skyrocketing domestic inflation. The shortage of funds in the bond market drives up market interest rates while also widening credit spreads. With a sharp upward trend of interest rates for more than six months, the fear of the market has spread out of control. Some even raise concerns that if this continues well into next year, Minsky Moment that all market participants dread could take place.

If the panic felt by market participants overwhelms reasonable decision making, the market is likely to see a race to disposal of assets, which could lead to the growth of non-performing assets and rising costs. At a time of economic turmoil, the role of financial market stabilization facilities would come to the fore. Government intervention through such stabilization facilities would be justifiable to avoid the market collapse driven by panic selling and ensure even partial operation of market functions. This intervention could stabilize the market, contributing to enhancing the welfare of economic players. In this respect, the Korean government’s plan for providing liquidity to corporate bond and short-term money markets is expected to have positive and significant effects on the recovery of market functions.

Against this backdrop, this article intends to present types of financial market stabilization facilities that could be used to address the shortage of funds, and to explore how to utilize them to prepare for a potential large-scale credit event. For your reference, this article was prepared before relevant government measures were released on October 23 and aims to analyze universal characteristics required for financial market stabilization facilities, rather than conducting an ex-post assessment of the October 23 measures.

Types and characteristics of Korea’s financial market stabilization facilities: The Covid-19 pandemic era

As for various financial market stabilization facilities adopted by the Korean government, the bond market stabilization fund (BMSF), P-CBOs, the quick bond takeover program, and the stock market stabilization fund (SMSF) are commonly used. Among them, the BMSF, P-CBOs, and the quick bond takeover program could improve poor capital circulation through the market by fixing blockages in capital flow when corporate funding is impeded by market strains, thereby reducing the risk of corporate insolvency. Accordingly, they seem to be more effective mechanisms in providing financial support for companies. Considering its primary goal of boosting stock prices, the SMSF may only have a marginal effect on revitalizing capital inflow.

In the midst of the domestic financial market turmoil triggered by the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, Korea’s fiscal authorities unveiled the aforementioned stabilization measures to normalize financial market functions.1) The BMSF has been established to provide liquidity to companies suffering a temporary lack of funds due to strains in the bond market and to prevent credit spreads from widening excessively. The government decided to add KRW 10 trillion to the existing BMSF of KRW 10 trillion—established during the 2008 global financial crisis—to alleviate the Covid 19-induced liquidity crunch in the bond market and provide liquidity to financially strapped companies. A total of 84 financial institutions including banks, securities firms, insurance firms, and government-sponsored financial institutions have contributed to creating the fund. Its investment targets include corporate bonds, CP of blue-chip companies, asset-backed short-term bonds, and financial bonds. The BMSF establishment plan and its operational details were announced on March 19, and March 24, 2022, respectively. After the first capital call for KRW 3 trillion, it commenced purchasing corporate bonds on April 2, 2022.

P-CBOs aim to stabilize the corporate bond market and support corporate financing. As the name suggests, they are designed to take over corporate bonds in the bond issuance market and securitize them in the form of collateralized bond obligations (CBOs). P-CBOs were issued in the total amount of KRW 6.7 trillion (KRW 5 trillion added to the first issuance of KRW 1.7 trillion) to support the issuance of corporate bonds for medium-sized enterprises and large companies that suffered Covid 19-induced liquidity shortages. As the first step of P-CBO issuance, the Korea Development Bank, Korea’s policy bank, takes over corporate bonds for sale to main creditor banks and the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund. And then P-CBOs are issued after credit reinforcement is conducted by the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund.

The quick bond takeover program is designed to support companies (SMEs and large companies) that wrestle with corporate bond redemption as their bonds come to maturity around the same time. Under the program, the Korea Development Bank will take over 80 percent of corporate bonds issued by such troubled companies. Upon the maturity of bonds, companies redeem 20 percent of the bonds while the Korea Development Bank rolls over the remaining 80 percent. Through credit reinforcement by the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund, most corporate bonds taken over by the Korea Development Bank (80 percent of issued bonds) are disposed of in the market in the form of P-CBOs while some are sold to creditor banks to diversify credit risks. With the 2020 quick bond takeover program, a net amount of KRW 2.2 trillion was injected into companies.

The SMSF has been created through contributions by various financial institutions to serve as a buffer zone in the stock market, for the purpose of alleviating a dramatic stock price slump and excessive market volatility. This fund should be in principle managed temporarily until the stock market rebounds and its investment only targets representative market indexes not to affect the prices of individual stocks. Like the BMSF, it secures funding through capital calls and invests in representative indexes of the stock market (ex, KOSPI200). As for financial institutions investing in the fund, their contributions could be subject to a relaxed capital adequacy ratio (risk weight). During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, five financial holding companies, 18 leading financial firms in banking, insurance and securities sectors and securities institutions (Korea Exchange, Korea Securities Depository, Korea Financial Investment Association) contributed a total of KRW 10.7 trillion to the fund, which, however, was not put to use because the stock market rallied swiftly. The SMSF can be distinguished from other stabilization tools in that it plays a minor role in providing funds to companies, despite its impact of mitigating a decline in stock prices.

Types and characteristics of US financial market stabilization facilities

Financial market stabilization facilities that the Fed operates in consultation with the US government at a time of financial or economic crises can be roughly categorized into the liquidity provision program, the capital market products purchase program and the loan support program. To compare with Korea’s stabilization mechanisms, this article analyzes key features of capital market products purchase programs utilized by the US, especially including the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) for CP purchases, the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) for corporate bond purchases, and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) for supporting the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS). The prominent feature commonly observed in those programs is role division and cooperative system between the Fed and the US government. In other words, the Fed is responsible for funding and the government (the Department of the Treasury) assumes the credit risk posed by the operation of such facilities. Generally, financial market stabilization facilities play a role in stabilizing the mentality of market participants to ensure that market functions well in a crisis. To this end, emergency funds large enough to quell market jitters should be provided swiftly. As most financial institutions are highly likely to face a liquidity squeeze during a crisis, funding from financial institutions’ contributions cannot be implemented expeditiously and has limitations in securing sufficient funds. To solve this problem, the Fed has decided to mobilize its monetary power, rather than obligating private financial firms to pay contributions into those facilities.

After funding is secured, credit risk comes to the fore during the process of operating facilities. When purchasing corporate bonds or CP with inherent risks, financial market stabilization facilities might face a default on such bonds. The facilities try to minimize the possibility of any credit event by setting criteria for bonds or CP eligible for purchase but it is impossible to eliminate the possibility of a default. In the US, any risk posed by default on products purchased by stabilization programs is borne by the Treasury while the Fed is separated from credit risk. This mechanism is based on the principle that the Fed responsible for establishing the nation’s monetary policy can cooperate in funding but it should not act as a final authority that assumes credit risk arising therefrom. This means such credit risk should be taken on by the authorities in charge of financial industry policies. According to the principle, the US Treasury implements equity tranche investments in the facilities by using the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) to insulate the Fed’s funding from a potential default.

The CPFF and TALF were established during the 2008 global financial crisis. After the collapse of Lehman Brothers caused strains in the CP market, the Fed set up the first CPFF (2008) on October 27, 2008 through cooperation with the Treasury in a bid to urgently provide liquidity to the short-term money market. The CPFF was operated under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury made equity investments in the CPFF through the ESF. The CPFF set the criteria for CP eligible for purchase (eligible CP) and bought ordinary CP and ABCP by strictly complying with the criteria. To meet the criteria, CP should receive a rating of A-1/P-1/F1 or higher from major credit rating agencies. The facility fees were calculated as 10bp of the CPFF’s maximum balance amount, and the pricing was based on the 3-month Overnight Index Swap (OIS) +110bp. The Fed granted loans to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) created for CP purchases and the SPV bought eligible CP from registered PDs under the supervision of the New York Fed. After being established in 2008, the CPFF bought eligible CP until February 1, 2010 and came to an end with all CP reaching maturity on April 26, 2010. As no default event occurred for any CP purchased during that period, all of them were redeemed at maturity. As strains rose again in the short-term money market amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed started a new CPFF program (2020) on March 17, 2020. With the same structure as the CPFF (2008)’s, the CPFF (2020) bought CP until March 31, 2021, none of which fell into default.

The TALF is designed to meet the credit needs of households and small businesses. When households and small businesses suffered a severe credit crunch upon the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the Fed established the TALF (2008)—the support program for households and small businesses using asset-backed securities as collateral—in consultation with the Treasury Department on November 25, 2008. As is the case with the CPFF, the TALF was operated under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury made equity investments in the TALF through the ESF. The collateral eligible for asset-backed securities (ABS) under the TALF is limited to student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA). The same facility fees of 10bp as the CPFF’s were charged, and the pricing was based on 30-day Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) +150bp for CLOs, Federal Fund Rate +75bp for the SBA-guaranteed loans, and 2-year OIS +125bp for collateral of other ABS. The TALF (2008) started providing funds to the ABS market in March 2009 and ended on June 30, 2010. A new TALF program (2020) was created on March 23, 2020 and stopped making new loans as of December 31, 2020.

The PMCCF and SMCCF were established in 2020 to provide liquidity to the corporate bond market. They did not exist during the 2008 global financial crisis but the Fed created these facilities on March 23, 2020 through cooperation with the Treasury Department, with the aim of easing strains in the corporate bond market. As their names suggest, the PMCCF is a program designed to purchase corporate bonds in the primary market while the SMCCF aims to buy corporate bonds in the secondary market. As with the TALF and CPFF, the PMCCF and SMCCF were managed under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the Treasury, using the ESF, made equity investments in the facilities. Corporate bonds that the PMCCF could purchase should have a credit rating of BBB-/Baa3 or higher as of March 22, 2020. To be eligible for the PMCCF, a company that met the requirement prior to March 22 but failed to maintain the required credit rating thereafter should be rated BB-/Ba3 or higher at least. The credit rating requirement equally applied to the SMCCF. As for the PMCCF, pricing would vary by issuing companies depending on market conditions and eligible issuers have to pay facility fees of 100bp. On the other hand, the SMCCF does not charge any extra facility fees and purchases corporate bonds at a fair market price because if the secondary market charges additional facility fees, corporate bond holders are not incentivized to sell their bond holdings to the SMCCF. The PMCCF and SMCCF ceased purchasing corporate bonds on December 31, 2020.

Financial market stabilization facilities: Comparison and policy implications

A comparative analysis of stabilization mechanisms adopted by the US and Korea reveals the following differences. First, Korea is highly dependent on private financial institutions to secure funding for stabilization facilities, while the US uses the Fed’s monetary power. Although some criticize the use of the Fed’s monetary power, it is worth noting its advantages including swift funding and availability of large-scale, long-term funding. Raising funds from private financial institutions requires a multilateral agreement on the allocation of contributions and procedures for consent. Accordingly, funding through a central bank is more beneficial given that speed is of great importance in financial or economic turmoil. Furthermore, contributions made by the private sector have limitations in expanding the funding amount above a certain level and if a crisis prolongs, the effect of such a funding method would be limited.

Second, credit risk arising from the operation of stabilization facilities is assumed by the US fiscal authorities (the Treasury Department), whereas credit risk in Korea could be shared by private financial institutions contributing to such facilities. If the government bears credit risk, this could trigger a controversy over moral hazards. Amid a financial or economic crisis, however, it is necessary to put priority on the normal operation of market functions, rather than concerns about potential moral hazards. This implies risk-taking activities by the government can be justifiable at times of crisis, which the Korean government needs to consider when operating relevant mechanisms.

Third, financial market stabilization programs of the US are segmented by market and among them, the intervention in the short-term money market is implemented for the first step. Compared with the US, Korea is less likely to operate different programs for each market and has yet to fully recognize the urgency of the short-term money market. As stated above, financial market stabilization facilities of the US—each specializing in the CP market, primary market, secondary market and ABS market—could be laser-focused on respective problems. As shown in the 2008 and 2020 cases, the intervention in the CP market should be first implemented to provide funds to companies, to be followed by measures targeting the corporate bonds and ABS markets. In contrast, Korea has drawn no clear distinction between the corporate bond market and the short-term money market comprised of CP and short-term electronic bonds. Accordingly, both corporate bonds and CP are purchased by Korea’s BMSF. P-CBOs are structured to support the ABS market but in terms of economic substance, it acts more like a support program for the corporate bond market. On top of that, Korea is less aware of the need for government intervention in the short-term money market, compared with the US.

Fourth, stabilization programs of the US reflect the costs of liquidity support in pricing by adding pricing fees, while Korea’s programs rarely require pricing fees as its policy focuses on support for companies or investors. As shown in the US cases, the CPFF, TALF and PMCCF charge pricing fees of 110bp, 75bp-150bp and 100bp, respectively. The SMCCF is the only facility not adding pricing fees. Aside from the SMCCF, the level of pricing fees is considerably high, which suggests that such support programs are not equivalent to government subsidization. This stems from the philosophy that beneficiaries of stabilization programs ought to bear the cost of relevant financial support. This is in stark contrast to Korea’s stabilization programs that generally tend to apply market interest rates or lower to pricing. Such a mechanism is underpinned by the perception that demanding financially strapped companies to pay the cost of such benefits is too harsh and that it is necessary to support their survival by providing benefits. Concerns have been raised that without pricing fees, emergency fund support by financial market stabilization facilities could encourage moral hazards. When it comes to the operation of stabilization programs, it seems reasonable for beneficiaries of liquidity support to bear a certain level of costs.

Lastly, although stabilization programs of the US hardly intervene in the stock market, such intervention can be observed in Korea. Various facilities run by the Fed usually function within the realm of debt instrument-based fund transactions, none of which, however, backs capital flow into the stock market. The comparative analysis results are summed up in the following table.

When financial market conditions deteriorate severely, the government should implement market stabilization measures rapidly and resolutely. If the possibility that financial firms or private companies go bankrupt increases sharply amid strong signs of market risk, financial market stabilization measures should be executed immediately on a massive scale. Soaring market interest rates are aggravating the financial market environment of Korea. The need for stabilization facilities is growing once again following the March 2020 Covid-19 crisis. In this respect, the government measures for providing liquidity to the market announced on October 23 are deemed a swift and proper response to deal with those worrying developments. Considering the potential recurrence of a liquidity squeeze, the government should work on additional countermeasures proactively.

As financial market stabilization facilities serve as a safeguard against a financial crisis, their execution method and process should be thoroughly examined and manualized before any crisis occurs. A manual for how to operate such facilities could make a huge difference between life and death for every company faced with a financial crisis. Even after being put into action several times, Korea’s stabilization programs have not been fully manualized in terms of funding methods and risk taking, which requires aggressive efforts to improve the current financial market stabilization regime.

1) Financial Services Commission, March 19, 2020, Covid-19 package programs for public welfare and financial stability, press release.

Financial Services Commission, March 24, 2020, Covid-19 financial market stabilization measures, press release.

Financial Services Commission, March 27, 2020, The government will implement package programs of KRW 100 trillion or more for supporting public welfare and financial stability, together with 14 related financial institutions, press release.