Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Declining Interest Rate Sensitivity of the US Real Economy and its Implications

Publication date Jun. 27, 2023

Summary

Despite the Fed’s steep rate hikes in response to unprecedented inflation, the US economy remains in good shape and its growth prospects are being revised up. This article analyzes the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy by applying various economic analysis methodologies. The analysis finds that the interest rate sensitivity of the US real economy has declined considerably. Improvement in the conduct of monetary policy, financial innovation and deregulation, and supply-side structural shifts have been pointed out as contributors to less interest rate sensitivity. In this respect, it should be noted that a decline in the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy may increase uncertainty over the estimation of the neutral real interest rate, which serves as a reference for monetary policy, and the high-price, high-interest rate environment may have a prolonged impact.

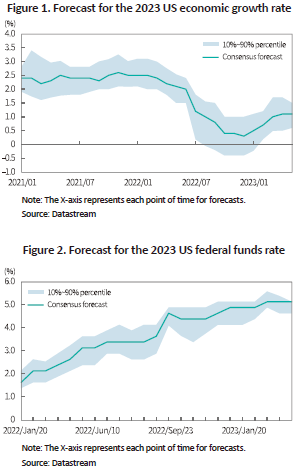

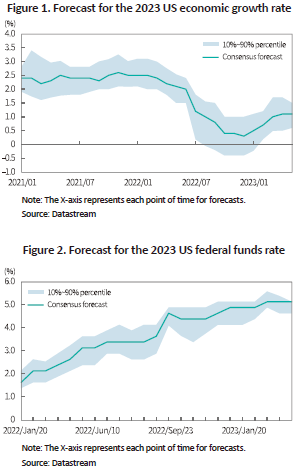

The IMF raised its forecast for US economic growth for 2023 to 1.7% on May 26.1) This figure is close to the potential growth rate (1.8%-1.9%) that represents the economic fundamentals of the US, which is a far cry from major forecasters’ prediction that the US recession may be imminent. Figure 1 shows how the US economic growth outlook for 2023 has changed from the beginning of 2021 to the present, suggesting that in the second half of 2022, not a few economic forecasters predicted negative growth. However, as the US economy exhibits a stronger-than-expected growth trend, its growth forecast has been gradually revised upward. The IMF forecast is in parallel with the ones presented by other forecasting institutions in a broader sense.

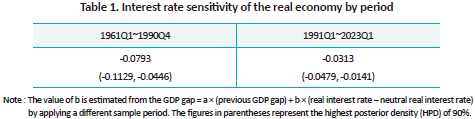

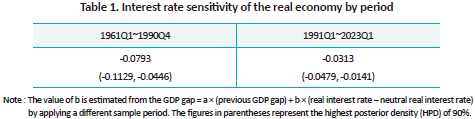

The prevailing negative view of the US economy can be attributed to the highest inflation level since the 1980s and the resultant steep rate hikes by the US Fed. In other words, such a negative outlook is underpinned by the perception that a sharp rise in interest rates will lead to a tight labor market and a fall in investments, slowing down demand. In the survey of how the end-2023 US benchmark rate is projected in each time frame as shown in Figure 2, what is interesting is that the monetary policy forecast at the end of last year when an economic recession was foreseen is not much different from the current outlook.

The combination of the two forecasts presented above suggests that the monetary tightening effect of rate hikes by the US has not been as great as initially expected. This result may stem from a sharp decline in the interest rate sensitivity of the US real economy or a longer policy lag—the period within which monetary tightening is reflected in the real economy—or interest rates not being high enough. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic occurred, it was pointed out that the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy may have been significantly mitigated by prolonged low inflation resulting from a lack of demand, although interest rates remained low in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

An empirical analysis of weakening interest rate sensitivity of the US economy

In this article, a semi structural model2) is established to empirically examine the changes in interest rate sensitivity of the real economy. An IS curve illustrates the relationship between the GDP gap (= actual GDP - potential GDP representing economic fundamentals) and the interest rate gap (= real interest rate - neutral real interest rate corresponding to equilibrium interest rate). An analysis of the IS curve finds that its slope corresponds to the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy. If the inverse correlation between the real economy and interest rates is taken into account, the IS curve has a negative slope, and the higher the absolute value, the greater the interest rate sensitivity. Table 1 shows the estimation result during the sample period divided into intervals between 1961Q1 and 1990Q4 and between 1991Q1 and 2023Q1. As shown in Table 1, interest rate sensitivity of the real economy has lessened immensely in recent years, compared to the past.

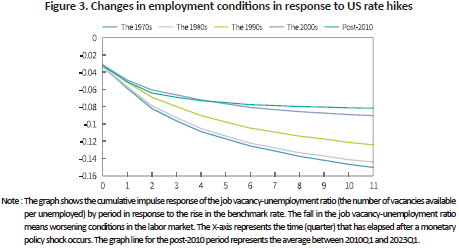

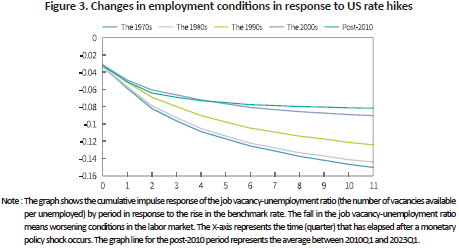

In the meantime, it is possible to examine the time-varying effect of monetary policy by applying the time-varying parameter vector autoregression model in which the relationship between real economic variables changes over time, rather than by arbitrarily dividing the sample period. Figure 3 shows how the job vacancy-unemployment ratio (the number of vacancies available per unemployed), which reflects labor market tightness, responds to monetary policy shocks by period. In response to the benchmark rate hikes, the number of vacancies has fallen while unemployment has increased, thereby curtailing the job vacancy-unemployment ratio. It is notable that by period, the labor market’s reaction to monetary policy has been reduced remarkably since the 2000s, compared to the 1970s and 1980s. Despite the difference in response intensity by period, the policy lag hardly seems to have lengthened as monetary policy normally takes effect after a lapse of two to three quarters.

Contributors to declining interest rate sensitivity of the real economy

Previous studies present contributors to the decline in interest rate sensitivity of the real economy as follows. First, it is found that the conduct of monetary policy has been improved thanks to a better understanding of economic fluctuations (Clarida et al., 2000; Boivin et al., 2011). Unlike in the 1960s and 1970s, central banks are working on stabilizing expected inflation for households and corporates in order to keep inflation expectations of the public from triggering price instability. As a result, the volatility of macroeconomic variables such as GDP or inflation has been immensely lowered, which has made the real economy insensitive to changes in the interest rate. In addition to the benchmark rate, greater use of monetary policy tools such as quantitative easing and forward guidance is also believed to have contributed to curtailing the benchmark rate’s influence.

Second, the relationship between interest rates and the real economy may have become loose because credit constraints on low-credit households and corporate borrowers have been eased by financial market innovation and deregulatory measures such as the abolition of Regulation Q (Dynan et al., 2005). For instance, if the market interest rate exceeds the upper limit of deposit interest rates under Regulation Q, which sets ceilings on interest rates that banks pay on deposits, financial institutions’ ability to offer loans is limited. Since the demise of Regulation Q, the cost of borrowing from banks has climbed while credit supply has marginally shrunk, making rate hikes less likely to lead to a contraction in the real economy. Furthermore, as household debt in the US has been reduced and fixed-rate loans have taken up a larger share, especially in the housing market since the global financial crisis, borrowers’ interest burden has not multiplied, thereby further weakening the impact of rate hikes. Bloomberg has reported3) that the share of floating-rate debt in the US mortgage pile has shrunk to about 5% from around 40% in 2006, and more than 40% of fixed-rate loans were locked in cheap loans during the Covid-19 pandemic with the interest rate level mostly remaining at 4%, much lower than the current benchmark rate.

Third, structural changes in the supply sector such as the expansion of supply chains driven by globalization seem to have accelerated the decline in interest rate sensitivity (Gamber & Hung, 2001; Sajedi & Thwaites, 2016; Forbes, 2019). Amid the emergence of multinational US companies, their production process is being partially carried out overseas. As a result, the impact of a shift in US monetary policy on production costs has been reduced, whereas global factors have had a greater impact on US prices. On top of that, demand for capital expenditures has been dampened by a price decline in capital goods on the back of the expansion of trade, which has also contributed to easing interest rate sensitivity.

Implications for monetary policy and the financial market

What are the implications that such macroeconomic changes will provide for monetary policy and the financial market? First of all, it should be noted that the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy has weakened considerably to the extent that major economic forecasters have presented wrong predictions. This has escalated uncertainty over the monetary policy paths of central banks. In particular, uncertainty about the estimation of the neutral real interest rate, which serves as a reference for the benchmark rate, has increased. The neutral real interest rate cannot be observed directly and should be estimated through a model in that it is the equilibrium interest rate that neither stimulates nor restricts the real economy. If the real economy is loosely connected to interest rates, it inevitably intensifies uncertainties when estimating the neutral real interest rate. Accordingly, it becomes difficult to determine whether monetary policy is tight enough to achieve the equilibrium level and thus, monetary policy paths may be employed on an ad hoc basis to respond to economic indicators for a considerable period of time. The May FOMC meeting minutes reveal that even within the Fed, opinions are sharply divided between an interest rate freeze and an additional hike regarding the future interest rate policy direction, well demonstrating that there is great uncertainty about the neutral real interest rate level that aligns with recent economic conditions. The difficulty in selecting an appropriate monetary policy direction is not limited to the Fed. Central banks of Australia and Canada have resumed interest rate increases after temporarily pausing their interest rate hiking campaign.

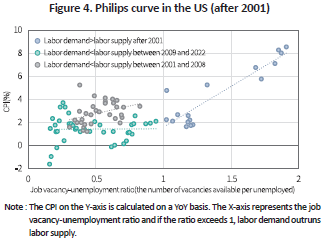

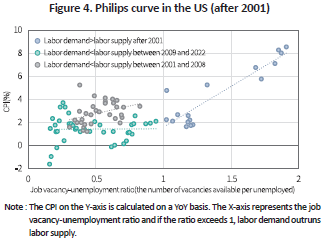

It is also noteworthy that given the analysis result presented in Figure 3 and previous studies, monetary tightening predominantly affects the real economy including employment conditions within a short period of time. In this respect, the effect of rate hikes, which was concentrated in the second and third quarters of 2022, is expected to wear off in the second half of this year. In fact, some financial institutions such as Goldman Sachs predict that the US economy will grow in 2024 and 2025 without any sign of recession, which is similar to this year’s growth trend. In this regard, it is necessary to examine the Philips curve in Figure 4 that shows the relationship between inflation and labor market conditions or the job vacancy-unemployment ratio. After the global financial crisis, the sluggish labor market (the job vacancy-unemployment ratio<1) caused the slope of the Philips curve to approach zero before the Covid-19 crisis occurred and thus, the relationship between the two variables appeared to disappear. As labor shortages (the job vacancy-unemployment ratio>1) have recently intensified, however, a clear positive relationship between employment conditions and prices has been restored. If the Philips curve is taken into account, a slowdown in the labor market is a prerequisite for price stability. But it is worth considering that US employment conditions becoming less sensitive to interest rates, coupled with the lack of immigrants and early retirement of the elderly in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, may lead to a prolonged supply and demand imbalance in the labor market. If this happens, the US economy will keep staying in the region with the job vacancy-unemployment ratio of more than 1 in Figure 4. If this risk becomes a reality, high levels of inflation and interest rates may have a lingering effect on the market, contrary to the financial market’s expectation for a potential shift in monetary policy stance.

1) The IMF forecast was raised by 0.3%p from the January 2023 forecast (1.4%p) and by 0.1%p from the April forecast (1.6%p).

2) Along with the IS curve explained above, the model includes the Philips curve representing the relationship between inflation and the GDP gap, Okun’s law describing the relationship between employment conditions and the GDP gap, the Taylor rule which is a response function of central banks’ monetary policy, and the Fisher equation about the relationship between nominal interest rates and real interest. Data used for estimation are US quarterly GDP, the PCE price index, the federal funds rate, and the unemployment rate.

3) Bloomberg, March 4, 2023, Sorry, Fed, most US mortgage rates were locked in during pandemic lows.

References

Boivin, J., Kiley, M.T., Mishkin, F.S., 2011, How has the monetary transmission mechanism evolved over time?, Handbook of Monetary Economics 3a, 369-422.

Clarida, R., Gali, J., Gertler, M., 2000, Monetary policy rules and macroeconomic stability: Evidence and some theory, Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(1), 147-180.

Dynan, K., Elmendorf, D., Sichel, D., 2005, Can financial innovation help to explain the reduced volatility of economic activity?, Journal of Monetary Economics 53(1), 123-150.

Forbes, K., 2019, Has globalization changed the inflation process?, BIS working papers No.791.

Gamber, E., Hung, J., 2001, Has the rise in globalization reduced U.S. inflation in the 1990s?, Economic Inquiry 39(1), 58-73.

Sajedi, R., Thwaites, G., 2016, Why are real interest rates so low? The role of the relative price of investment goods, IMF Economic Review 64(4), 635-659.

The prevailing negative view of the US economy can be attributed to the highest inflation level since the 1980s and the resultant steep rate hikes by the US Fed. In other words, such a negative outlook is underpinned by the perception that a sharp rise in interest rates will lead to a tight labor market and a fall in investments, slowing down demand. In the survey of how the end-2023 US benchmark rate is projected in each time frame as shown in Figure 2, what is interesting is that the monetary policy forecast at the end of last year when an economic recession was foreseen is not much different from the current outlook.

The combination of the two forecasts presented above suggests that the monetary tightening effect of rate hikes by the US has not been as great as initially expected. This result may stem from a sharp decline in the interest rate sensitivity of the US real economy or a longer policy lag—the period within which monetary tightening is reflected in the real economy—or interest rates not being high enough. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic occurred, it was pointed out that the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy may have been significantly mitigated by prolonged low inflation resulting from a lack of demand, although interest rates remained low in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

An empirical analysis of weakening interest rate sensitivity of the US economy

In this article, a semi structural model2) is established to empirically examine the changes in interest rate sensitivity of the real economy. An IS curve illustrates the relationship between the GDP gap (= actual GDP - potential GDP representing economic fundamentals) and the interest rate gap (= real interest rate - neutral real interest rate corresponding to equilibrium interest rate). An analysis of the IS curve finds that its slope corresponds to the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy. If the inverse correlation between the real economy and interest rates is taken into account, the IS curve has a negative slope, and the higher the absolute value, the greater the interest rate sensitivity. Table 1 shows the estimation result during the sample period divided into intervals between 1961Q1 and 1990Q4 and between 1991Q1 and 2023Q1. As shown in Table 1, interest rate sensitivity of the real economy has lessened immensely in recent years, compared to the past.

In the meantime, it is possible to examine the time-varying effect of monetary policy by applying the time-varying parameter vector autoregression model in which the relationship between real economic variables changes over time, rather than by arbitrarily dividing the sample period. Figure 3 shows how the job vacancy-unemployment ratio (the number of vacancies available per unemployed), which reflects labor market tightness, responds to monetary policy shocks by period. In response to the benchmark rate hikes, the number of vacancies has fallen while unemployment has increased, thereby curtailing the job vacancy-unemployment ratio. It is notable that by period, the labor market’s reaction to monetary policy has been reduced remarkably since the 2000s, compared to the 1970s and 1980s. Despite the difference in response intensity by period, the policy lag hardly seems to have lengthened as monetary policy normally takes effect after a lapse of two to three quarters.

Contributors to declining interest rate sensitivity of the real economy

Previous studies present contributors to the decline in interest rate sensitivity of the real economy as follows. First, it is found that the conduct of monetary policy has been improved thanks to a better understanding of economic fluctuations (Clarida et al., 2000; Boivin et al., 2011). Unlike in the 1960s and 1970s, central banks are working on stabilizing expected inflation for households and corporates in order to keep inflation expectations of the public from triggering price instability. As a result, the volatility of macroeconomic variables such as GDP or inflation has been immensely lowered, which has made the real economy insensitive to changes in the interest rate. In addition to the benchmark rate, greater use of monetary policy tools such as quantitative easing and forward guidance is also believed to have contributed to curtailing the benchmark rate’s influence.

Second, the relationship between interest rates and the real economy may have become loose because credit constraints on low-credit households and corporate borrowers have been eased by financial market innovation and deregulatory measures such as the abolition of Regulation Q (Dynan et al., 2005). For instance, if the market interest rate exceeds the upper limit of deposit interest rates under Regulation Q, which sets ceilings on interest rates that banks pay on deposits, financial institutions’ ability to offer loans is limited. Since the demise of Regulation Q, the cost of borrowing from banks has climbed while credit supply has marginally shrunk, making rate hikes less likely to lead to a contraction in the real economy. Furthermore, as household debt in the US has been reduced and fixed-rate loans have taken up a larger share, especially in the housing market since the global financial crisis, borrowers’ interest burden has not multiplied, thereby further weakening the impact of rate hikes. Bloomberg has reported3) that the share of floating-rate debt in the US mortgage pile has shrunk to about 5% from around 40% in 2006, and more than 40% of fixed-rate loans were locked in cheap loans during the Covid-19 pandemic with the interest rate level mostly remaining at 4%, much lower than the current benchmark rate.

Third, structural changes in the supply sector such as the expansion of supply chains driven by globalization seem to have accelerated the decline in interest rate sensitivity (Gamber & Hung, 2001; Sajedi & Thwaites, 2016; Forbes, 2019). Amid the emergence of multinational US companies, their production process is being partially carried out overseas. As a result, the impact of a shift in US monetary policy on production costs has been reduced, whereas global factors have had a greater impact on US prices. On top of that, demand for capital expenditures has been dampened by a price decline in capital goods on the back of the expansion of trade, which has also contributed to easing interest rate sensitivity.

Implications for monetary policy and the financial market

What are the implications that such macroeconomic changes will provide for monetary policy and the financial market? First of all, it should be noted that the interest rate sensitivity of the real economy has weakened considerably to the extent that major economic forecasters have presented wrong predictions. This has escalated uncertainty over the monetary policy paths of central banks. In particular, uncertainty about the estimation of the neutral real interest rate, which serves as a reference for the benchmark rate, has increased. The neutral real interest rate cannot be observed directly and should be estimated through a model in that it is the equilibrium interest rate that neither stimulates nor restricts the real economy. If the real economy is loosely connected to interest rates, it inevitably intensifies uncertainties when estimating the neutral real interest rate. Accordingly, it becomes difficult to determine whether monetary policy is tight enough to achieve the equilibrium level and thus, monetary policy paths may be employed on an ad hoc basis to respond to economic indicators for a considerable period of time. The May FOMC meeting minutes reveal that even within the Fed, opinions are sharply divided between an interest rate freeze and an additional hike regarding the future interest rate policy direction, well demonstrating that there is great uncertainty about the neutral real interest rate level that aligns with recent economic conditions. The difficulty in selecting an appropriate monetary policy direction is not limited to the Fed. Central banks of Australia and Canada have resumed interest rate increases after temporarily pausing their interest rate hiking campaign.

It is also noteworthy that given the analysis result presented in Figure 3 and previous studies, monetary tightening predominantly affects the real economy including employment conditions within a short period of time. In this respect, the effect of rate hikes, which was concentrated in the second and third quarters of 2022, is expected to wear off in the second half of this year. In fact, some financial institutions such as Goldman Sachs predict that the US economy will grow in 2024 and 2025 without any sign of recession, which is similar to this year’s growth trend. In this regard, it is necessary to examine the Philips curve in Figure 4 that shows the relationship between inflation and labor market conditions or the job vacancy-unemployment ratio. After the global financial crisis, the sluggish labor market (the job vacancy-unemployment ratio<1) caused the slope of the Philips curve to approach zero before the Covid-19 crisis occurred and thus, the relationship between the two variables appeared to disappear. As labor shortages (the job vacancy-unemployment ratio>1) have recently intensified, however, a clear positive relationship between employment conditions and prices has been restored. If the Philips curve is taken into account, a slowdown in the labor market is a prerequisite for price stability. But it is worth considering that US employment conditions becoming less sensitive to interest rates, coupled with the lack of immigrants and early retirement of the elderly in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, may lead to a prolonged supply and demand imbalance in the labor market. If this happens, the US economy will keep staying in the region with the job vacancy-unemployment ratio of more than 1 in Figure 4. If this risk becomes a reality, high levels of inflation and interest rates may have a lingering effect on the market, contrary to the financial market’s expectation for a potential shift in monetary policy stance.

1) The IMF forecast was raised by 0.3%p from the January 2023 forecast (1.4%p) and by 0.1%p from the April forecast (1.6%p).

2) Along with the IS curve explained above, the model includes the Philips curve representing the relationship between inflation and the GDP gap, Okun’s law describing the relationship between employment conditions and the GDP gap, the Taylor rule which is a response function of central banks’ monetary policy, and the Fisher equation about the relationship between nominal interest rates and real interest. Data used for estimation are US quarterly GDP, the PCE price index, the federal funds rate, and the unemployment rate.

3) Bloomberg, March 4, 2023, Sorry, Fed, most US mortgage rates were locked in during pandemic lows.

References

Boivin, J., Kiley, M.T., Mishkin, F.S., 2011, How has the monetary transmission mechanism evolved over time?, Handbook of Monetary Economics 3a, 369-422.

Clarida, R., Gali, J., Gertler, M., 2000, Monetary policy rules and macroeconomic stability: Evidence and some theory, Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(1), 147-180.

Dynan, K., Elmendorf, D., Sichel, D., 2005, Can financial innovation help to explain the reduced volatility of economic activity?, Journal of Monetary Economics 53(1), 123-150.

Forbes, K., 2019, Has globalization changed the inflation process?, BIS working papers No.791.

Gamber, E., Hung, J., 2001, Has the rise in globalization reduced U.S. inflation in the 1990s?, Economic Inquiry 39(1), 58-73.

Sajedi, R., Thwaites, G., 2016, Why are real interest rates so low? The role of the relative price of investment goods, IMF Economic Review 64(4), 635-659.