Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Female Participation in the Labor Market and Fertility Rates: Insights from the Research of a Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences

Publication date Dec. 05, 2023

Summary

The 2023 Nobel Prize in Economic Science was awarded to Professor Claudia Goldin for her contributions to enhancing understanding of the factors influencing female labor force participation and the gender earnings gap. Over the past century, the gender earnings gap has stemmed from various factors such as discriminatory laws, stereotyped gender roles, limited educational opportunities and, constraints on job choices. However, even after these factors are controlled, the gender earnings gap still exists. Professor Goldin attributes this persistent disparity to the division of labor between men and women after childbirth and the intrinsic characteristics of jobs. Men tend to choose high-intensity jobs accompanied by high income, while women often take greater childcare responsibilities and opt for flexible work arrangements. This structural imbalance has resulted in the gender earnings gap. Korea experiences the highest gender earnings gap among OECD countries while suffering from lowest-low fertility. Selection of flexible works or career interruptions can widen such a gap and increase the opportunity costs associated with childbirth, further accelerating the decline in fertility rates. The current situation urgently calls for the reform of the labor incentive structure to effectively address intertwined issues such as the gender earnings gap, career interruptions for women and fertility rates. In other words, there is a growing need to transform the labor market structure that highly values long working hours and excessive workloads. This reform is not only essential to improve gender equality but also serves as a crucial task for efficiently deploying national talent and ensuring economic sustainability.

Professor Claudia Goldin from the Harvard Department of Economics was awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for her contributions to labor economics. She conducted outstanding research on the fundamental causes of female labor force participation and gender earnings gap in the historical context. Professor Goldin provides an insightful interpretation based on specific data, demonstrating that factors influencing the gender earnings gap include occupational choices and education levels between men and women as well as dynamics within households and decision-making process.

Korea is currently facing challenges associated with women’s career interruption and declining fertility. Women’s active labor force participation and childbirth are essential for economic growth and development. Policy measures should be geared toward promoting equal opportunities and eliminating discrimination to support a work-life balance because they will pave the crucial foundation for creating a fair social environment and enhancing the life satisfaction of individuals.

To establish effective strategies to encourage female labor force participation and family formation, it is necessary to understand the complex relationships between occupational choices, family dynamics and fertility levels. Professor Goldin’s research provides a valuable opportunity to reassess and improve approaches to female labor force participation and fertility. Against this backdrop, this article takes a close look at her research and derives implications for addressing Korea’s challenges related to female labor force participation and low fertility.

Causes of gender income gap by era

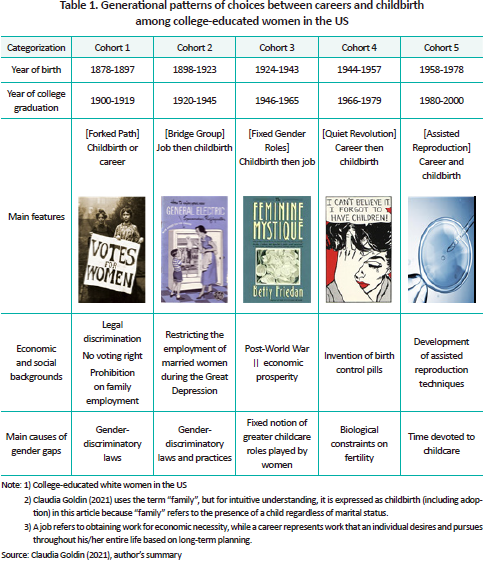

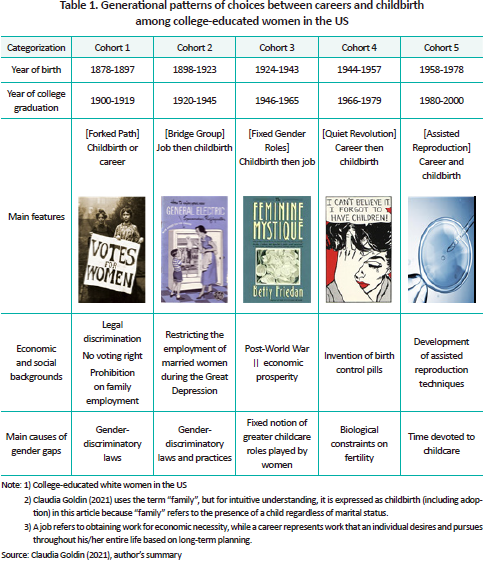

Through a historical examination, Professor Goldin analyzed how women entered the labor market and the causes of the gender earnings gap over a century, focusing on women who graduated from college in the US. Her research categorized them into five groups based on the time of college graduation, highlighting that women’s optimal choices between careers and family varied by generation and different factors contributed to earnings gaps.1)

Cohort 1 is composed of women born in the late 19th century who graduated from college in the early 20th century. They could not reconcile career and family and suffered from obvious legal and social discrimination against women, including denying them the right to vote. The majority of women in this cohort chose family over career, while only a small number of them opted for a successful career track, giving up marriage and childbirth.

Cohort 2 consisting of women who graduated from college between 1920 and 1945 is referred to as the “Bridge Group”. Their activities became prominent during a period characterized by increased demand for labor in the market. The use of household appliances relieved the burden of domestic chores, while the development of typewriters led to higher demand for office work, consequently boosting the demand for the female workforce. As education served as a means for women to enhance their value in the labor market, this pushed up the demand for secondary education and led to women’s higher education levels. Despite these advancements, however, the lack of jobs resulting from the Great Depression ended up prohibiting the employment of married women. During this period, women tended to leave the labor market after getting married.

Women in Cohort 3 represent the generation that graduated from college at the time of the economic boom after the end of World War Ⅱ. This generation saw a significant increase in the number of college graduates and showed a strong will to advance into society. The post-war trend of early marriage emerged in that many tended to rush into marriage immediately after graduation. As contraceptive pills were not yet invented, they had no control over the time of pregnancy and thus, tended to have children shortly after marriage, consequently leading to career interruptions. While the proportion of women who pursued both work and family climbed compared to the previous generation, women with preschool-age children showed low participation in the labor market. There was a prevailing belief that pursuing a career by women with young children could have a negative impact on children, representing traditional gender roles. With the lack of childcare infrastructure, child-rearing was considered women’s responsibility. After their children started school, around 70% of women returned to the workforce. Consequently, women became inclined to choose majors that allowed them to leave and return to the labor market.

Cohort 4 is characterized by the generation of “Quiet Revolution”.2) Women of this generation could decide on labor force participation and careers on their own will, which was primarily attributable to the invention of contraceptive pills. The ability to plan the timing of pregnancies gave them the opportunity to develop careers throughout their lives and to seek professional advancement, rather than having a job to merely make a living. During this period, women delayed the time of starting a family and established a life plan of pursuing their career first and giving birth later. Notably, the scientific fact that infertility rates increased with age had not yet been discovered at that time. As a result, the career-first plans fell apart and some women involuntarily lost opportunities to establish a family.

Women in Cohort 5 graduated from college after the 1980s, and they had a strong desire to pursue both a career and a family. They pushed back the timing of childbirth to pursue their careers as those in Cohort 4 did. However, the advancement in assisted reproductive technologies such as in-vitro fertilization allowed them to have a child at a later age. Women were able to adjust the timing of childbirth thanks to the development of medical technologies, increasing the possibility of pregnancy.

Since the late 1980s, women have gained the opportunity to simultaneously pursue careers and childbirth. Legal discrimination that posed an obstacle to women’s social advancement, as experienced by previous generations, has been eliminated and traditional gender stereotypes have improved. In terms of laws and social norms, explicit discrimination against women has been considerably addressed. Over the past century, 45% of the 155 major movements for women’s rights in the US occurred between 1963 and 1973, which promoted legal rights for women.3) Women’s education levels have increased, and legal and regulatory factors contributing to the gender earnings gap have been significantly reduced, for example, thanks to the introduction of the Equal Pay Act.

Flexibility in working hours and gender earnings gap

Despite these changes, there remains an income gap between men and women. Even after controlling visible factors such as education levels and work experience between them, the gender income divergence has not been considerably narrowed.

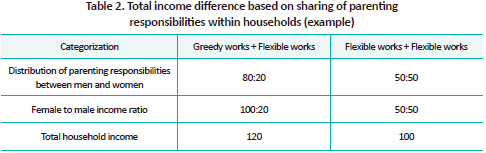

Professor Goldin suggests that the recent earnings gap is attributed to the structure of the labor market, rather than external factors. This divergence particularly stems from the nature of jobs, which arises in situations where men and women, who are responsible for caregiving, have to choose between “greedy works” and “flexible works”. Under the payment system for greedy works, the longer the working hours, the larger the hourly wages. These works require long hours and constant availability according to an on-call schedule. In contrast, flexible works involve minimal business trips or overnight work due to fewer immediate tasks, and require limited interaction with other people, allowing for flexible time management. Unlike greedy works, these works hardly provide incentives for working longer as long hours do not translate into an increase in hourly compensation.

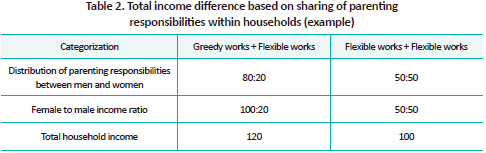

Family members who contribute more to parenting within households often choose flexible works over greedy ones because they need to be constantly available. If a family member is primarily responsible for childcare, the remaining family members bear a lower childcare burden, allowing them to stay on standby for work and focus on their job. As greedy works pay more income per hour when working hours increase, households where family members engage in both greedy works and flexible works enjoy higher total income, compared to households where childcare responsibilities are equally divided. It implies that if inequality in childcare responsibilities can be accepted by family members, they can reach the optimized level of household income.

However, it should be noted that the choice of jobs among family members is not made equally between men and women. It has been generally observed that men often opt for greedy works while women tend to choose flexible ones. This tendency leads to the sustained gender income disparity as women, who often bear a greater burden for caregiving, have to experience a significant reduction in income after a child is born, due to the nature of flexible works.

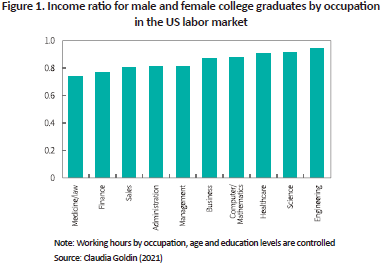

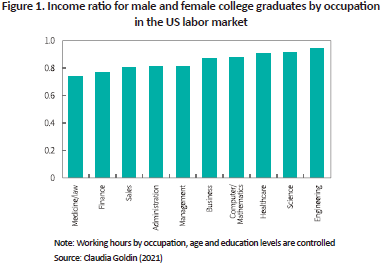

Income in many professions shows a non-linear relationship with working hours. The level of income often varies depending on the value that the working hours-based compensation system attributes to time flexibility. This difference affects the degree of gender income divergence between industries. In the US, women engaging in science and engineering fields earn 94% of what their male counterparts earn, while the income earned by women in finance represents only 77% of that of men.

This result stems from characteristics of each industry, rather than a prevalence of low gender equality awareness and strong gender biases among members of a specific industry.4) The fields such as engineering, science, computer and mathematics—where time pressure is low and interpersonal interactions are limited—reveal smaller gender income gaps. However, gender gaps are more pronounced in management, administration, sales, medicine, and law industries that put heavy emphasis on deadlines and interpersonal relationships.

The gender earnings gap persists not only during childbirth or child-rearing stages but throughout one’s whole life. Research conducted on workers with MBA or JD degrees has found that the gender earnings gap widened noticeably over time after graduation.5)

Status of female labor force participation and low fertility in Korea

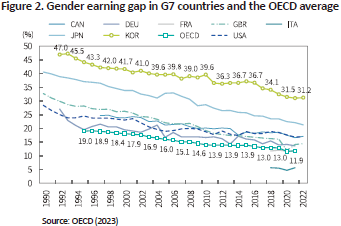

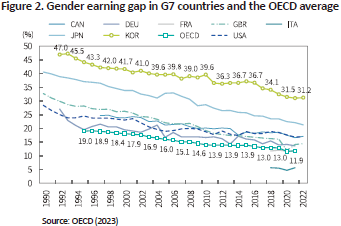

In Figure 2 illustrating the average gender earnings gap among G7 countries and OECD members, the income inequality between men and women shows a global declining trend, with the OECD average sliding to 11.9% in 2021 from 19.0% in 1995. Korea has also narrowed its gender earnings gap from 47.0% in 1992 to 31.2% in 2022, making progress in gender inequality in earnings. Despite this progress, Korea still represents a larger gender earnings gap, compared to G7 countries. Furthermore, it exhibits a substantial difference with Japan having the second-highest gender earning gap among G7 countries, and recent indications suggest that this difference will likely be even larger. Although various efforts have been put into reducing the gender earnings gap, it remains a challenging issue in Korea.

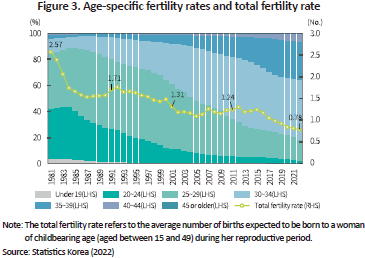

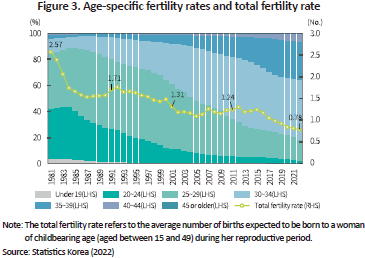

Another imminent challenge faced by Korea is declining fertility. Korea already entered the phase of lowest-low fertility in the 2000s. The total fertility rate, a key indicator of population growth, dropped from 1.31 in 2001 to 0.98 in 2018, falling below one child per woman. In the third quarter of 2023, the total fertility rate further decreases to 0.7, aggravating the current situation.

Furthermore, an analysis of age-specific fertility rates of women reveals a noticeable delay in family planning throughout their life cycles. The fertility rate for women under 30 stood at 60.7% in 2001, which plunged to 18.5% in 2022. In addition, the proportion of older women, especially those aged 35, showed a considerable increase from 7.5% in 2001 to 35.6% in 2022. As indicated in the characteristics of Cohort 4 and Cohort 5 suggested by Professor Goldin, women tend to delay or avoid marriage and childbirth as they become more eager to achieve higher education and careers. This trend is likely to accelerate population decline and aging and bring about demographic changes. It is also expected to impede economic growth and aggravate the burden on healthcare and social welfare.

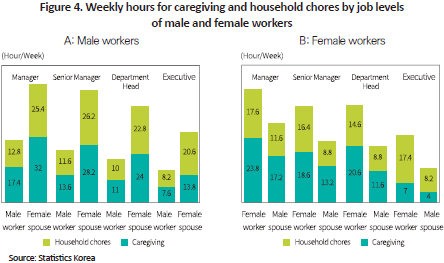

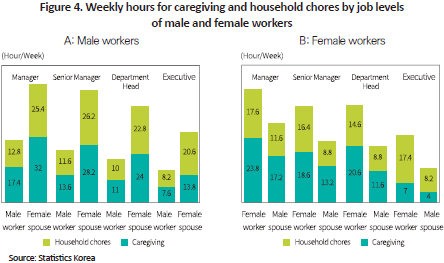

When examining job level-specific characteristics between male and female workforce, it is hard to say that caregiving and household chores are evenly divided between genders. This article divides job levels into manager, senior manager, department head, and executive ranks and investigates how much time individuals and their spouses spend on caregiving and household responsibilities. It is found that male workers spend only half of what their spouses spend on caregiving and household chores across all job levels. In contrast, female workers devote more time to caregiving and household chores compared to their husbands. This even holds true for women who have built successful careers up to executive levels.

Even in a comparison of male and female workers with the same job levels, the time spent by female workers on caregiving and household chores is still longer. For instance, male workers at the manager level spend an average of 30.2 hours per week on household chores, while their female counterparts spend 41.4 hours on average. In executive levels, male and female workers spend 15.8 hours and 24.4 hours on average, respectively, showing a similar difference.

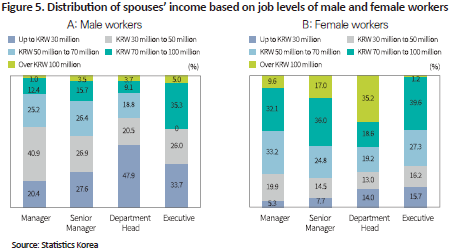

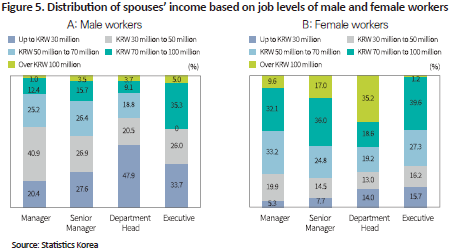

The distribution of spouses’ income based on job levels of male and female workers sheds some light on the division of household responsibilities and family dynamics. Across all levels, male workers whose spouses earn less than KRW 30 million account for 20% to 50%, and the proportion tends to rise as the job level increases from manager to department head levels. On the contrary, female workers whose spouses earn KRW 30 million or less make up a smaller proportion, while those whose spouses are high-income earners, earning more than KRW 70 million, represent nearly half. It should be noted that this result has been derived based on uncontrolled factors such as the presence of children and education levels. Accordingly, it seems improper to interpret that the income gaps among spouses of male and female workers solely stem from the choice of jobs with high time flexibility. However, given that across all job levels, female workers devote more time per week to caregiving and household chores compared to their male counterparts, it can be assumed that career choices based on the nature of jobs have had a considerable impact on the earnings gap within a family.

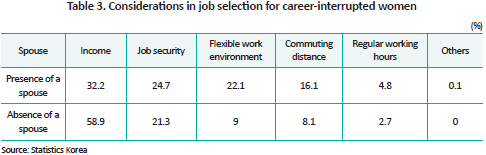

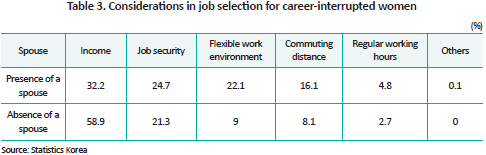

A statistical analysis reveals that career-interrupted women prioritize the time flexibility of jobs over individual goals to maximize career advancement and growth when exiting the labor market or choosing from jobs. According to a 2022 survey on career-interrupted women, 71.8% of respondents said that their departure from employment was the result of their own choice, rather than the company’s decision or contract termination. Furthermore, 70.3% mentioned that they would have kept working if it had not been for issues related to childcare or children’s education.

As for career-interrupted women, considerations for career choices vary depending on the presence of a spouse. These women without spouses put the highest priority on securing income for a livelihood, while those with spouses prefer a flexible work environment as well as income and job security.

Professor Goldin’s research findings indicate that the persistent gender earnings gap can be attributed to the nature of jobs, which men and women choose after childbirth. The divergence between men and women has been significantly narrowed thanks to changes in social norms and increased education levels over the past century, but the gender disparity still exists. Professor Goldin refers to this as the “Last Chapter”6) to be overcome to achieve a fair relationship between men and women.

This is also applicable to Korea. Apart from the gender earnings gap, Korea faces another urgent and important challenge, low fertility. These two issues are intertwined, mutually affecting female labor force participation and family planning. Many women decide to exit the labor market for childrearing or opt for flexible work arrangements, which has unintended consequences of aggravating the gender earnings gap.

Achieving an increase in fertility and a reduction in the gender income disparity is not an easy task, without improvements in social practices and norms and the childrearing environment. As the responsibility for caregiving increases, imposing constraints on one’s career pursuit and work continuity, the earnings gap between men and women widens. Consequently, the opportunity costs associated with childbirth rise. If childbirth and caregiving responsibilities require women to make more sacrifices, it is likely to have an adverse impact on women’s decisions to have children, potentially worsening declining fertility.

Implications and future challenges

Resolving explicit discrimination between women and men experienced by past generations is a relatively straightforward task. If women lack opportunities or rights, or they are blocked from having certain professions, the solution would be the establishment of regulations. However, what makes it more complex are inexplicit and hidden issues that lead to gender divergence even under equal conditions.

A case in point is the phenomenon where men opt for highly demanding jobs and women choose flexible work arrangements. It is hard to assert that these decisions made within households are discriminatory and irrational on the side of women. As mentioned above, they may be the result of rational role division among family members to optimize household income.

However, when faced with the choice between high-intensity jobs and caregiving, women tend to disproportionately opt for the caregiving role. In this respect, it is worth considering whether female workers voluntarily choose flexible works due to a preference for assuming the caregiver role. Do these women prefer flexibility because they put more value on childrearing than on maximizing personal income and career success? Alternatively, could it be that women, being more irrational than men, choose family and caregiving over maximizing personal income throughout their lives? A plausible explanation is that systematic factors resulting from hidden constraints other than individual choices and preferences may come into play.

Professor Goldin argues that the labor system structure should be improved to achieve gender equality. She emphasizes the need to overhaul the labor market system that incentivizes long working hours and to create more jobs to enhance flexibility. However, she has not provided concrete suggestions for how to expand the flexibility of working hours.7)

To tackle this challenge, the compensation gap between high-paying jobs that entail excessive workloads and jobs accompanied by flexible working hours should be reduced. Such a change would have an impact of reducing relative income from high-intensity work, thereby encouraging more workers to choose flexible works. However, companies driven by profit maximization are not motivated to voluntarily change their compensation system to accommodate job flexibility.

It is encouraging that men pursuing the work-life balance are on the rise. According to the 2021 survey conducted by Statistics Korea, 27% of eligible workers use the flexible working hours system, with 40% of men utilizing staggered work schedules and more than half of men tapping into telecommuting or remote work arrangements. As more and more workers prioritize family and their personal lives over work, companies are expected to build an incentive system that aligns with the needs of top talent.

In terms of the childcare support system, there remains a significant difference in the parental leave utilization ratio of male workers to female workers, which needs to be improved. Among those eligible for parental leave, 47.3% of women took parental leave in 2021 while only 6.3% of men did. Although more than half of respondents said that parental leave was easy to use, the actual use was very limited due to the perception that taking parental leave may result in financial and non-financial disadvantages. Accordingly, it is essential to take precautionary measures to prevent any practical disadvantages in terms of wage, performance evaluation, promotion, or career advancement when employees take parental leave. Professor Goldin suggests that achieving equality in the labor market does not necessarily require government intervention or greater household responsibilities taken by men.8) Given that Korea is characterized by a larger gender gap compared to the US and low fertility potentially impeding economic development, policy measures should be implemented to solve this issue.

On top of that, there is a need for a change in the perception within households. In the modern era, the arrangement where one family member focuses on a job bound by time constraints and the other takes more parenting responsibilities has been regarded as a rational choice for optimizing household income. However, it is necessary to question the rationality of the criteria based on which the arrangement is made. Women may become dissatisfied when they experience career interruptions or are unable to give full attention to work due to childcare. Similarly, men may feel regrettable for not having sufficient time with family members at the cost of career success. When determining how household responsibilities are divided between men and women, it is crucial to consider both the utility derived from income and the value to be realized by fair sharing of parenting responsibilities between men and women and give more weight to the value of fair division of responsibilities.

Korea achieved rapid economic growth in the late 20th century. Unlike the US, which experienced gradual development over the 19th and 20th centuries, it gained economic development in a short period of time. For this reason, generations with various values coexist in Korean households including: the older generation with discriminatory views on gender roles and grandmothers with fewer education opportunities (Cohort 1); mothers who learned traditional stereotypes about women’s roles as homemakers (Cohort 2); aunts who returned to work after experiencing career interruptions due to childbirth (Cohort 3); the current generation who gives up childbirth for career success (Cohort 4) and who struggles for achieving a work-family balance (Cohort 5). With the coexistence of generations with diverse values, discriminatory norms and beliefs persist, potentially affecting the lives of women and men. Compared with rapid economic growth, the social perception of gender roles and the labor market have not kept pace with these changes, which calls for continuous efforts to raise awareness about relevant issues.

1) Claudia Goldin (2021)

2) Female labor force participation has evolved gradually, but a revolutionary shift, not gradual progress, occurred in the 1960s, the era for Cohort 4. During this period, women’s economic activities began to be considered continuous, not short-term. Women began to pursue careers based on personal identity rather than job availability. In addition, they gained the power to jointly decide labor force participation, rather than merely playing a supportive role in assisting their spouses. These changes can be called a revolutionary shift during the era (Goldin, 2006).

3) Goldin (2023)

4) Goldin (2023)

5) Goldin (2010), Goldin (2014)

6) Goldin (2014)

7) Yun, J.Y. (2022)

8) Goldin (2014)

References

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., Katz, L., 2010, Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Financial and Corporate Sectors, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2, 228–255.

Goldin, C., 2006, The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family, Richard T. Ely Lecture.

Goldin, C., 2014, A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter, American Economic Review 104(4), 1091-1119.

Goldin, C., 2023, Why women won, NBER working paper 31762.

Goldin, C., Katz, L., 2002, The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women's career and marriage decisions, Journal of Political Economy 110(4), 730-770.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 2023. 10. 09, Scientific background to the Sveriges Riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel 2023.

OECD, 2023, Gender wage gap (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7cee77aa-en (Accessed on 15 November 2023)

[Korean]

Yun, J.Y., 2022, Why does gender income inequality persist?, Korea Journal of Labor Studies 28(1), 383-390.

Claudia Goldin, 2021, Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity, Thinking Power.

Statistics Korea, August 30, 2023, Birth statistics for the year 2022, press release.

Korea is currently facing challenges associated with women’s career interruption and declining fertility. Women’s active labor force participation and childbirth are essential for economic growth and development. Policy measures should be geared toward promoting equal opportunities and eliminating discrimination to support a work-life balance because they will pave the crucial foundation for creating a fair social environment and enhancing the life satisfaction of individuals.

To establish effective strategies to encourage female labor force participation and family formation, it is necessary to understand the complex relationships between occupational choices, family dynamics and fertility levels. Professor Goldin’s research provides a valuable opportunity to reassess and improve approaches to female labor force participation and fertility. Against this backdrop, this article takes a close look at her research and derives implications for addressing Korea’s challenges related to female labor force participation and low fertility.

Causes of gender income gap by era

Through a historical examination, Professor Goldin analyzed how women entered the labor market and the causes of the gender earnings gap over a century, focusing on women who graduated from college in the US. Her research categorized them into five groups based on the time of college graduation, highlighting that women’s optimal choices between careers and family varied by generation and different factors contributed to earnings gaps.1)

Cohort 1 is composed of women born in the late 19th century who graduated from college in the early 20th century. They could not reconcile career and family and suffered from obvious legal and social discrimination against women, including denying them the right to vote. The majority of women in this cohort chose family over career, while only a small number of them opted for a successful career track, giving up marriage and childbirth.

Cohort 2 consisting of women who graduated from college between 1920 and 1945 is referred to as the “Bridge Group”. Their activities became prominent during a period characterized by increased demand for labor in the market. The use of household appliances relieved the burden of domestic chores, while the development of typewriters led to higher demand for office work, consequently boosting the demand for the female workforce. As education served as a means for women to enhance their value in the labor market, this pushed up the demand for secondary education and led to women’s higher education levels. Despite these advancements, however, the lack of jobs resulting from the Great Depression ended up prohibiting the employment of married women. During this period, women tended to leave the labor market after getting married.

Women in Cohort 3 represent the generation that graduated from college at the time of the economic boom after the end of World War Ⅱ. This generation saw a significant increase in the number of college graduates and showed a strong will to advance into society. The post-war trend of early marriage emerged in that many tended to rush into marriage immediately after graduation. As contraceptive pills were not yet invented, they had no control over the time of pregnancy and thus, tended to have children shortly after marriage, consequently leading to career interruptions. While the proportion of women who pursued both work and family climbed compared to the previous generation, women with preschool-age children showed low participation in the labor market. There was a prevailing belief that pursuing a career by women with young children could have a negative impact on children, representing traditional gender roles. With the lack of childcare infrastructure, child-rearing was considered women’s responsibility. After their children started school, around 70% of women returned to the workforce. Consequently, women became inclined to choose majors that allowed them to leave and return to the labor market.

Cohort 4 is characterized by the generation of “Quiet Revolution”.2) Women of this generation could decide on labor force participation and careers on their own will, which was primarily attributable to the invention of contraceptive pills. The ability to plan the timing of pregnancies gave them the opportunity to develop careers throughout their lives and to seek professional advancement, rather than having a job to merely make a living. During this period, women delayed the time of starting a family and established a life plan of pursuing their career first and giving birth later. Notably, the scientific fact that infertility rates increased with age had not yet been discovered at that time. As a result, the career-first plans fell apart and some women involuntarily lost opportunities to establish a family.

Women in Cohort 5 graduated from college after the 1980s, and they had a strong desire to pursue both a career and a family. They pushed back the timing of childbirth to pursue their careers as those in Cohort 4 did. However, the advancement in assisted reproductive technologies such as in-vitro fertilization allowed them to have a child at a later age. Women were able to adjust the timing of childbirth thanks to the development of medical technologies, increasing the possibility of pregnancy.

Since the late 1980s, women have gained the opportunity to simultaneously pursue careers and childbirth. Legal discrimination that posed an obstacle to women’s social advancement, as experienced by previous generations, has been eliminated and traditional gender stereotypes have improved. In terms of laws and social norms, explicit discrimination against women has been considerably addressed. Over the past century, 45% of the 155 major movements for women’s rights in the US occurred between 1963 and 1973, which promoted legal rights for women.3) Women’s education levels have increased, and legal and regulatory factors contributing to the gender earnings gap have been significantly reduced, for example, thanks to the introduction of the Equal Pay Act.

Flexibility in working hours and gender earnings gap

Despite these changes, there remains an income gap between men and women. Even after controlling visible factors such as education levels and work experience between them, the gender income divergence has not been considerably narrowed.

Professor Goldin suggests that the recent earnings gap is attributed to the structure of the labor market, rather than external factors. This divergence particularly stems from the nature of jobs, which arises in situations where men and women, who are responsible for caregiving, have to choose between “greedy works” and “flexible works”. Under the payment system for greedy works, the longer the working hours, the larger the hourly wages. These works require long hours and constant availability according to an on-call schedule. In contrast, flexible works involve minimal business trips or overnight work due to fewer immediate tasks, and require limited interaction with other people, allowing for flexible time management. Unlike greedy works, these works hardly provide incentives for working longer as long hours do not translate into an increase in hourly compensation.

Family members who contribute more to parenting within households often choose flexible works over greedy ones because they need to be constantly available. If a family member is primarily responsible for childcare, the remaining family members bear a lower childcare burden, allowing them to stay on standby for work and focus on their job. As greedy works pay more income per hour when working hours increase, households where family members engage in both greedy works and flexible works enjoy higher total income, compared to households where childcare responsibilities are equally divided. It implies that if inequality in childcare responsibilities can be accepted by family members, they can reach the optimized level of household income.

However, it should be noted that the choice of jobs among family members is not made equally between men and women. It has been generally observed that men often opt for greedy works while women tend to choose flexible ones. This tendency leads to the sustained gender income disparity as women, who often bear a greater burden for caregiving, have to experience a significant reduction in income after a child is born, due to the nature of flexible works.

Income in many professions shows a non-linear relationship with working hours. The level of income often varies depending on the value that the working hours-based compensation system attributes to time flexibility. This difference affects the degree of gender income divergence between industries. In the US, women engaging in science and engineering fields earn 94% of what their male counterparts earn, while the income earned by women in finance represents only 77% of that of men.

This result stems from characteristics of each industry, rather than a prevalence of low gender equality awareness and strong gender biases among members of a specific industry.4) The fields such as engineering, science, computer and mathematics—where time pressure is low and interpersonal interactions are limited—reveal smaller gender income gaps. However, gender gaps are more pronounced in management, administration, sales, medicine, and law industries that put heavy emphasis on deadlines and interpersonal relationships.

The gender earnings gap persists not only during childbirth or child-rearing stages but throughout one’s whole life. Research conducted on workers with MBA or JD degrees has found that the gender earnings gap widened noticeably over time after graduation.5)

Status of female labor force participation and low fertility in Korea

In Figure 2 illustrating the average gender earnings gap among G7 countries and OECD members, the income inequality between men and women shows a global declining trend, with the OECD average sliding to 11.9% in 2021 from 19.0% in 1995. Korea has also narrowed its gender earnings gap from 47.0% in 1992 to 31.2% in 2022, making progress in gender inequality in earnings. Despite this progress, Korea still represents a larger gender earnings gap, compared to G7 countries. Furthermore, it exhibits a substantial difference with Japan having the second-highest gender earning gap among G7 countries, and recent indications suggest that this difference will likely be even larger. Although various efforts have been put into reducing the gender earnings gap, it remains a challenging issue in Korea.

Another imminent challenge faced by Korea is declining fertility. Korea already entered the phase of lowest-low fertility in the 2000s. The total fertility rate, a key indicator of population growth, dropped from 1.31 in 2001 to 0.98 in 2018, falling below one child per woman. In the third quarter of 2023, the total fertility rate further decreases to 0.7, aggravating the current situation.

Furthermore, an analysis of age-specific fertility rates of women reveals a noticeable delay in family planning throughout their life cycles. The fertility rate for women under 30 stood at 60.7% in 2001, which plunged to 18.5% in 2022. In addition, the proportion of older women, especially those aged 35, showed a considerable increase from 7.5% in 2001 to 35.6% in 2022. As indicated in the characteristics of Cohort 4 and Cohort 5 suggested by Professor Goldin, women tend to delay or avoid marriage and childbirth as they become more eager to achieve higher education and careers. This trend is likely to accelerate population decline and aging and bring about demographic changes. It is also expected to impede economic growth and aggravate the burden on healthcare and social welfare.

When examining job level-specific characteristics between male and female workforce, it is hard to say that caregiving and household chores are evenly divided between genders. This article divides job levels into manager, senior manager, department head, and executive ranks and investigates how much time individuals and their spouses spend on caregiving and household responsibilities. It is found that male workers spend only half of what their spouses spend on caregiving and household chores across all job levels. In contrast, female workers devote more time to caregiving and household chores compared to their husbands. This even holds true for women who have built successful careers up to executive levels.

Even in a comparison of male and female workers with the same job levels, the time spent by female workers on caregiving and household chores is still longer. For instance, male workers at the manager level spend an average of 30.2 hours per week on household chores, while their female counterparts spend 41.4 hours on average. In executive levels, male and female workers spend 15.8 hours and 24.4 hours on average, respectively, showing a similar difference.

The distribution of spouses’ income based on job levels of male and female workers sheds some light on the division of household responsibilities and family dynamics. Across all levels, male workers whose spouses earn less than KRW 30 million account for 20% to 50%, and the proportion tends to rise as the job level increases from manager to department head levels. On the contrary, female workers whose spouses earn KRW 30 million or less make up a smaller proportion, while those whose spouses are high-income earners, earning more than KRW 70 million, represent nearly half. It should be noted that this result has been derived based on uncontrolled factors such as the presence of children and education levels. Accordingly, it seems improper to interpret that the income gaps among spouses of male and female workers solely stem from the choice of jobs with high time flexibility. However, given that across all job levels, female workers devote more time per week to caregiving and household chores compared to their male counterparts, it can be assumed that career choices based on the nature of jobs have had a considerable impact on the earnings gap within a family.

A statistical analysis reveals that career-interrupted women prioritize the time flexibility of jobs over individual goals to maximize career advancement and growth when exiting the labor market or choosing from jobs. According to a 2022 survey on career-interrupted women, 71.8% of respondents said that their departure from employment was the result of their own choice, rather than the company’s decision or contract termination. Furthermore, 70.3% mentioned that they would have kept working if it had not been for issues related to childcare or children’s education.

As for career-interrupted women, considerations for career choices vary depending on the presence of a spouse. These women without spouses put the highest priority on securing income for a livelihood, while those with spouses prefer a flexible work environment as well as income and job security.

Professor Goldin’s research findings indicate that the persistent gender earnings gap can be attributed to the nature of jobs, which men and women choose after childbirth. The divergence between men and women has been significantly narrowed thanks to changes in social norms and increased education levels over the past century, but the gender disparity still exists. Professor Goldin refers to this as the “Last Chapter”6) to be overcome to achieve a fair relationship between men and women.

This is also applicable to Korea. Apart from the gender earnings gap, Korea faces another urgent and important challenge, low fertility. These two issues are intertwined, mutually affecting female labor force participation and family planning. Many women decide to exit the labor market for childrearing or opt for flexible work arrangements, which has unintended consequences of aggravating the gender earnings gap.

Achieving an increase in fertility and a reduction in the gender income disparity is not an easy task, without improvements in social practices and norms and the childrearing environment. As the responsibility for caregiving increases, imposing constraints on one’s career pursuit and work continuity, the earnings gap between men and women widens. Consequently, the opportunity costs associated with childbirth rise. If childbirth and caregiving responsibilities require women to make more sacrifices, it is likely to have an adverse impact on women’s decisions to have children, potentially worsening declining fertility.

Implications and future challenges

Resolving explicit discrimination between women and men experienced by past generations is a relatively straightforward task. If women lack opportunities or rights, or they are blocked from having certain professions, the solution would be the establishment of regulations. However, what makes it more complex are inexplicit and hidden issues that lead to gender divergence even under equal conditions.

A case in point is the phenomenon where men opt for highly demanding jobs and women choose flexible work arrangements. It is hard to assert that these decisions made within households are discriminatory and irrational on the side of women. As mentioned above, they may be the result of rational role division among family members to optimize household income.

However, when faced with the choice between high-intensity jobs and caregiving, women tend to disproportionately opt for the caregiving role. In this respect, it is worth considering whether female workers voluntarily choose flexible works due to a preference for assuming the caregiver role. Do these women prefer flexibility because they put more value on childrearing than on maximizing personal income and career success? Alternatively, could it be that women, being more irrational than men, choose family and caregiving over maximizing personal income throughout their lives? A plausible explanation is that systematic factors resulting from hidden constraints other than individual choices and preferences may come into play.

Professor Goldin argues that the labor system structure should be improved to achieve gender equality. She emphasizes the need to overhaul the labor market system that incentivizes long working hours and to create more jobs to enhance flexibility. However, she has not provided concrete suggestions for how to expand the flexibility of working hours.7)

To tackle this challenge, the compensation gap between high-paying jobs that entail excessive workloads and jobs accompanied by flexible working hours should be reduced. Such a change would have an impact of reducing relative income from high-intensity work, thereby encouraging more workers to choose flexible works. However, companies driven by profit maximization are not motivated to voluntarily change their compensation system to accommodate job flexibility.

It is encouraging that men pursuing the work-life balance are on the rise. According to the 2021 survey conducted by Statistics Korea, 27% of eligible workers use the flexible working hours system, with 40% of men utilizing staggered work schedules and more than half of men tapping into telecommuting or remote work arrangements. As more and more workers prioritize family and their personal lives over work, companies are expected to build an incentive system that aligns with the needs of top talent.

In terms of the childcare support system, there remains a significant difference in the parental leave utilization ratio of male workers to female workers, which needs to be improved. Among those eligible for parental leave, 47.3% of women took parental leave in 2021 while only 6.3% of men did. Although more than half of respondents said that parental leave was easy to use, the actual use was very limited due to the perception that taking parental leave may result in financial and non-financial disadvantages. Accordingly, it is essential to take precautionary measures to prevent any practical disadvantages in terms of wage, performance evaluation, promotion, or career advancement when employees take parental leave. Professor Goldin suggests that achieving equality in the labor market does not necessarily require government intervention or greater household responsibilities taken by men.8) Given that Korea is characterized by a larger gender gap compared to the US and low fertility potentially impeding economic development, policy measures should be implemented to solve this issue.

On top of that, there is a need for a change in the perception within households. In the modern era, the arrangement where one family member focuses on a job bound by time constraints and the other takes more parenting responsibilities has been regarded as a rational choice for optimizing household income. However, it is necessary to question the rationality of the criteria based on which the arrangement is made. Women may become dissatisfied when they experience career interruptions or are unable to give full attention to work due to childcare. Similarly, men may feel regrettable for not having sufficient time with family members at the cost of career success. When determining how household responsibilities are divided between men and women, it is crucial to consider both the utility derived from income and the value to be realized by fair sharing of parenting responsibilities between men and women and give more weight to the value of fair division of responsibilities.

Korea achieved rapid economic growth in the late 20th century. Unlike the US, which experienced gradual development over the 19th and 20th centuries, it gained economic development in a short period of time. For this reason, generations with various values coexist in Korean households including: the older generation with discriminatory views on gender roles and grandmothers with fewer education opportunities (Cohort 1); mothers who learned traditional stereotypes about women’s roles as homemakers (Cohort 2); aunts who returned to work after experiencing career interruptions due to childbirth (Cohort 3); the current generation who gives up childbirth for career success (Cohort 4) and who struggles for achieving a work-family balance (Cohort 5). With the coexistence of generations with diverse values, discriminatory norms and beliefs persist, potentially affecting the lives of women and men. Compared with rapid economic growth, the social perception of gender roles and the labor market have not kept pace with these changes, which calls for continuous efforts to raise awareness about relevant issues.

1) Claudia Goldin (2021)

2) Female labor force participation has evolved gradually, but a revolutionary shift, not gradual progress, occurred in the 1960s, the era for Cohort 4. During this period, women’s economic activities began to be considered continuous, not short-term. Women began to pursue careers based on personal identity rather than job availability. In addition, they gained the power to jointly decide labor force participation, rather than merely playing a supportive role in assisting their spouses. These changes can be called a revolutionary shift during the era (Goldin, 2006).

3) Goldin (2023)

4) Goldin (2023)

5) Goldin (2010), Goldin (2014)

6) Goldin (2014)

7) Yun, J.Y. (2022)

8) Goldin (2014)

References

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., Katz, L., 2010, Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young Professionals in the Financial and Corporate Sectors, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2, 228–255.

Goldin, C., 2006, The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family, Richard T. Ely Lecture.

Goldin, C., 2014, A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter, American Economic Review 104(4), 1091-1119.

Goldin, C., 2023, Why women won, NBER working paper 31762.

Goldin, C., Katz, L., 2002, The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women's career and marriage decisions, Journal of Political Economy 110(4), 730-770.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 2023. 10. 09, Scientific background to the Sveriges Riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel 2023.

OECD, 2023, Gender wage gap (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7cee77aa-en (Accessed on 15 November 2023)

[Korean]

Yun, J.Y., 2022, Why does gender income inequality persist?, Korea Journal of Labor Studies 28(1), 383-390.

Claudia Goldin, 2021, Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity, Thinking Power.

Statistics Korea, August 30, 2023, Birth statistics for the year 2022, press release.