Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Monetary Policy Uncertainty in South Korea: Impacts and Policy Implications

Publication date Jun. 25, 2024

Summary

There have been ongoing uncertainty and concerns regarding future monetary policy in South Korea, as inflation has remained above the target for over three years despite continued monetary tightening.

My empirical analysis reveals that an increase in uncertainty about monetary policy in South Korea is associated with statistically significant drops in industrial production and stock prices, an increase in credit spreads, and the depreciation of the Korean won. These findings underscore the need for policy efforts aimed at reducing both the level and volatility of monetary policy uncertainty in order to promote economic and financial stability.

While conditional forward guidance on the likely future path of policy rates can be an effective tool for mitigating monetary policy uncertainty, it may also carry potential side effects. Therefore, the communication strategies of the monetary authority require careful scrutiny.

My empirical analysis reveals that an increase in uncertainty about monetary policy in South Korea is associated with statistically significant drops in industrial production and stock prices, an increase in credit spreads, and the depreciation of the Korean won. These findings underscore the need for policy efforts aimed at reducing both the level and volatility of monetary policy uncertainty in order to promote economic and financial stability.

While conditional forward guidance on the likely future path of policy rates can be an effective tool for mitigating monetary policy uncertainty, it may also carry potential side effects. Therefore, the communication strategies of the monetary authority require careful scrutiny.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the steep rise in inflation stemming from the economic crisis has led to a tight monetary policy in South Korea. The benchmark interest rate was raised by a total of three percentage points on ten occasions between August 2021 and January 2023, and has remained at around 3.5% since January 2023. The Domestic Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased steadily from October 2020 to July 2022, reaching a peak of 6.3% in July 2022, and then declined until July 2023 before rebounding in August 2023. Although the CPI reentered a declining phase in October 2023, the pace of disinflation has slowed down, and inflation in South Korea has hovered over its inflation target of 2% since April 2021. It is notable that despite the ongoing monetary tightening in South Korea, inflation has remained above the target for an extended period. Furthermore, as economic growth in the first quarter of this year far exceeded expectations, the Bank of Korea (BOK) revised upward its economic growth forecast for this year in May, compared to the February forecast (from 2.1% to 2.5%). The BOK also raised its consumer price inflation projection for the second half of 2024 from 2.3% to 2.4% and its core inflation forecast from 2.0% to 2.1%, respectively, taking into account factors such as improved growth trends and greater exchange rate volatility.

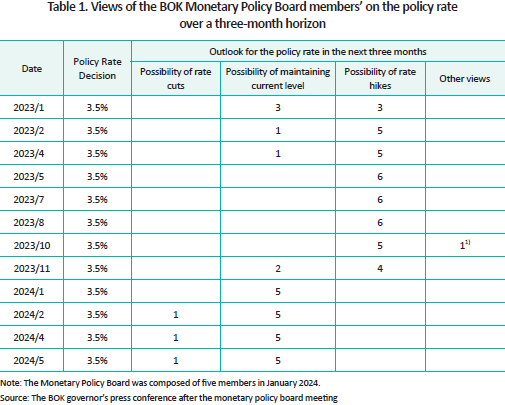

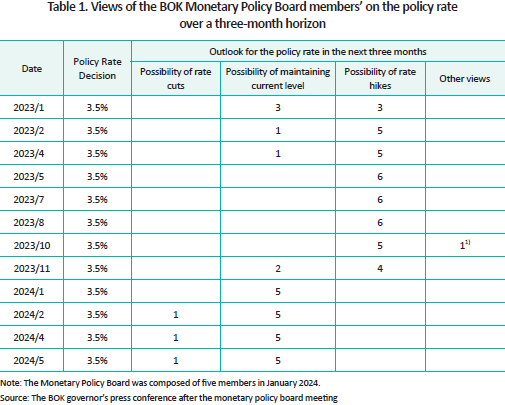

Table 1 presents the changes in the BOK Monetary Policy Board (MPB)’s outlook for the benchmark interest rate over a three-month horizon. Since October 2023, the number of MPB members advocating for a rate hike has decreased, and no views supporting interest rate rises have been presented this year. As a result, market concerns about further benchmark rate rises have diminished significantly, but uncertainty over the duration of the current monetary tightening and the timing and magnitude of potential rate cuts remains a persistent source of concern.

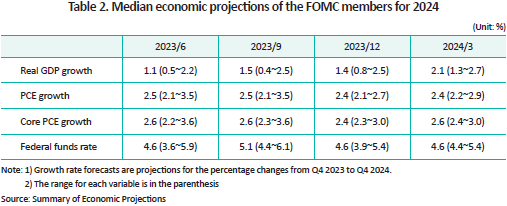

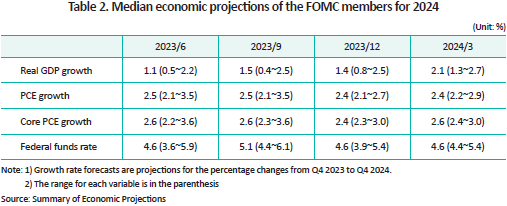

Expectations for a delay in US rate cuts also add to uncertainty regarding domestic monetary policy. Table 2 illustrates changes in the Fed members’ median projections for the US economic growth rate, inflation, and the federal funds rate on a year-on-year basis. The forecasts for inflation and the federal funds rate as of the end of this year, presented in December 2023, were revised down compared to the September 2023 forecasts, which raises expectations for the Fed’s rate cuts within 2024. However, the March 2024 forecasts for economic growth and the increase in the core PCE price index were adjusted upward compared to the December 2023 forecasts, reflecting a delayed slowdown in inflation and a stronger US economic recovery. Although the median forecast for the federal funds rate has remained unchanged, there has been an upward shift in the distribution of forecasts, delaying expectations for the Fed’s rate cuts and heightening uncertainty about their timing and magnitude. Notably, the Korea-US interest rate differential has reached an all-time high of 2% and the exchange rate between the two countries has remained elevated for an extended period. Consequently, expectations for delayed rate cuts in the US act as an additional constraint on the flexibility of Korea’s domestic monetary policy.

Despite a downward trend of inflation in South Korea, upside risks to domestic inflation have increased due to factors such as the recent surge in import prices spurred by high exchange rates, the rebound in expected inflation observed in May, rising producer prices, heightened exchange rate volatility, and geopolitical tensions. Furthermore, prolonged monetary tightening in the US and the record-high interest rate differential between Korea and the US are amplifying the ongoing uncertainty about the trajectory of domestic monetary policy.

Economic impacts of monetary policy uncertainty

Even if there is no direct change in the policy interest rate, heightened monetary policy uncertainty, as perceived in the private sector, can affect the decision-making of economic agents and investors. This uncertainty can potentially have adverse effects on both the real economy and capital markets. For example, the wait-and-see effect, a typical path for spreading uncertainty, suggests that increased economic uncertainty may postpone irreversible decisions such as business investments, employment, and durable goods consumption until uncertainty levels subside, thereby contracting the real economy (Bernanke, 1983; Bloom, 2009; Bloom, 2014; Eberly, 1994; Husted et al., 2020). In addition to the impact of worsening real economic conditions, such uncertainty can also negatively affect the capital markets by reducing investor participation.

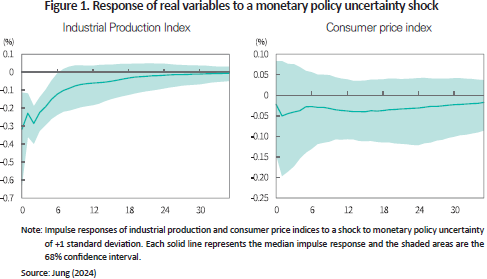

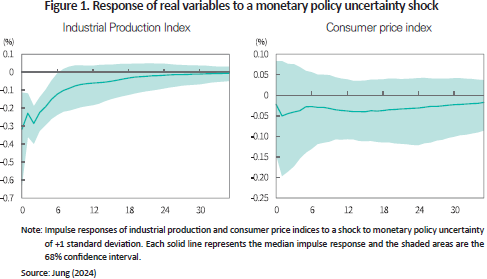

Figure 1 shows how domestic real economic variables respond to heightened monetary policy uncertainty shocks2) on a monthly basis.3) The increase in domestic monetary policy uncertainty significantly curtails industrial production over a six-month period, whereas demonstrating no significant impact on inflation. In addition to weakening aggregate demand through the wait-and-see effect, increased uncertainty can reduce the input of production factors and lead to their misallocation, thereby contracting aggregate supply (Bloom et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that despite increased monetary policy uncertainty shocks to the market, changes in aggregate supply an demand seem to offset each other, resulting in negligible effects on prices.

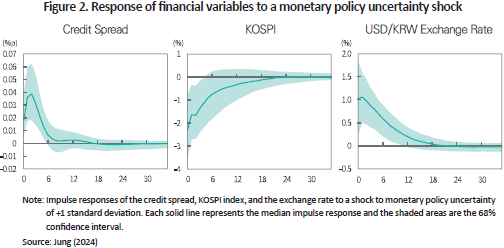

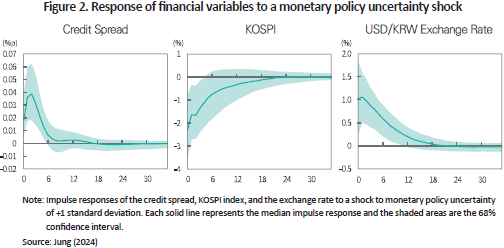

Figure 2 shows how domestic financial market variables react to monetary policy uncertainty shocks in South Korea. The analysis indicates that such shocks markedly widen the credit spread between 3-year AA-rated corporate bonds and government bonds, decrease the KOSPI significantly, and boost the US dollar to the Korean won (USD/KRW) exchange rate. The uncertainty can lead to a deterioration in the real economy, thereby amplifying credit risk for companies. Moreover, increased uncertainty can discourage domestic and foreign investors from participating in the Korean capital market, resulting in an increase in risk premiums demanded by investors. In addition, it can escalate the risk of won-denominated assets compared to foreign currency-denominated assets, potentially contributing to the depreciation of the Korean won. The impact of increased monetary policy uncertainty on the financial market can be understood as a combination of deteriorating real economic conditions, as reflected in the financial market, and changes in investor behavior.

In summary, the analysis reveals that the escalation of monetary policy uncertainty in South Korea has an adverse impact on the real economy and capital markets, leading to a contraction in industrial production, increased corporate financing costs, and a decline in stock indices, and also can contribute to the depreciation of the Korean won. These findings suggest that the expansion and volatility of monetary policy uncertainty can undermine the stability of the Korean real economy and financial market.

BOK’s forward guidance and monetary policy uncertainty

Central bank communication plays a crucial role in facilitating economic agents’ understanding of how monetary policies are implemented and in enhancing the predictability of future monetary policy directions by providing various information to the public (Blinder et al., 2008). Therefore, communication from monetary authorities can serve as an effective policy tool to mitigate the uncertainty perceived by economic agents and reduce the associated social costs. For example, Swanson (2006) finds that enhanced communication by the US Fed considerably reduced forecast errors of the private sector regarding future policy interest rates. Similarly, Chang and Feunou (2013) show that uncertainty about future interest rates in Canada declined on average following the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy announcement.

Since October 2022, the BOK has expanded its communication to the public by presenting the distribution of MPB members’ projections for the future policy rate over a three-month horizon at the Governor’s press conference immediately following monetary policy direction meetings.4) This conditional forward guidance, which presents policy rate forecasts based on the current assessment of future economic conditions, can mitigate the information asymmetry between the central bank and the public. By providing previously unavailable information, it also enhances the predictability of future monetary policy directions for economic agents. It is noteworthy that economic agents may misunderstand conditional forecasts, which are based on multiple assumptions, as a commitment to future policies. In this case, the credibility of the central bank could be compromised if a rapid change in economic conditions necessitates a policy decision divergent from the current outlook on policy rates (Mishkin, 2004; Issing, 2005). Although the BOK’s adoption of conditional forward guidance seems to help alleviate monetary policy uncertainty until recently (Jung, 2024), the persistence of this effect remains uncertain, prompting consideration of the following improvements.

First, any significant changes in the distribution of forecasts or divergence in opinions among MPB members should be clearly explained through sufficient data. A substantial shift in the distribution of policy rate projections or widening divergence in interest rate forecasts can cause the financial market to react sensitively, even in the absence of a direct shift in the policy interest rate stance, which potentially makes it challenging for the market to predict monetary policy paths (Couture, 2021). In South Korea, since the introduction of conditional forward guidance, there has been neither a noticeable difference in terminal interest rate forecasts among MPB members nor a sudden change in the forecast distribution. However, if such a case occurs in the future, it could amplify the uncertainty perceived by economic agents regarding monetary policy stance. To mitigate unintended side effects, sophisticated communication tools should be implemented, such as providing clear explanations and sufficient data regarding changes in the forecast distribution or differences in opinions among MPB members.

Second, each MPB member may be required to present the rationale behind their benchmark rate projections. In the current system, the common rationale of the group of members proposing the same opinion (possibility of rate cuts or hikes, possibility of maintaining the current level) is mentioned at the press conference, along with the distribution of MPB members’ projections, but each member’s rationale is not provided. MPB members who share the same forecast opinion may differ in their underlying rationale and assumptions.5) Despite the conditional nature of MPB members’ benchmark rate projections, which rely on the current assessment of expected economic conditions, there is a lack of information about the specific assumptions each member uses to justify their projections. This limits the market’s understanding of how each member has arrived at their projections. It may also cause the market to focus more on the figures themselves rather than the underlying rationale, which could undermine the credibility of the monetary authorities if future policy directions divulge from the current projections. To ensure that conditional forward guidance facilitates the market’s understanding of how monetary authorities implement policies, rather than simply managing expectations for future interest rates, the rationale for each projection should be presented individually. Therefore, it is advisable to disseminate a summary of each MPB member’s rationale for benchmark rate projections as it would enhance the effectiveness of conditional forward guidance.

The BOK has indicated that it is internally discussing the possibility of extending the horizon of conditional forward guidance beyond the current three months (Governor’s press conference on monetary policy direction, February 22, 2024). As the time horizon lengthens, the uncertainty of projections and the potential for errors will increase. Without sufficient explanation and data regarding the assumptions or rationale behind projections, repeated forecast errors could damage the credibility of the monetary authorities and cause market confusion. Therefore, if the forward guidance horizon is extended, it will be crucial to implement the aforementioned improvement measures.

1) It suggests that there should be flexibility in either raising or lowering the benchmark interest rate over the next three months.

2) I use the news-based monetary policy uncertainty index in South Korea measured by Cho & Kim (2023). This monthly index is based on the frequency of monetary policy uncertainty-related articles from major newspapers in South Korea. A news-based index can comprehensively reflect uncertainty about various aspects of economic policy measures, including what policy decisions will be made, when they will be implemented, and how they will affect the economy (Baker et al., 2016). It can also capture the uncertainty perceived by a wide range of economic agents, provided that the media reflects the interests of a broad readership (Husted et al., 2020).

3) To estimate the economic impacts of monetary policy uncertainty shocks in South Korea, a structural vector autoregression model is estimated using sign restrictions. The model includes seven endogenous variables: the industrial production index, call rate, Korean monetary policy uncertainty index, credit spread between 3-year AA-rated corporate bonds and government bonds, KOSPI, and USD/KRW exchange rate. Additionally, the US monetary policy uncertainty index (Baker et al., 2016), the US stock market volatility index, and the federal funds rate are included as exogenous variables.

4) Central banks that provide projections for future policy rates include the US Federal Reserve, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Norges Bank, and the Riskbank. Regarding the provision of forecasts, they differ in terms of the introduction timing, the frequency and manner, and the time horizon.

5) These assumptions may include whether the opinion is based on common economic outlook data or incorporates additional individual economic projection models or data, and how they assess domestic and international economic uncertainties.

References

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., 2016, Measuring economic policy uncertainty, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4), 1593-1636.

Bernanke, B. S., 1983, Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 98(1), 85-106.

Blinder, A. S., Ehrmann, M., Fratzscher, M., De Haan, J., Jansen, D. J., 2008, Central bank communication and monetary policy: A survey of theory and evidence, Journal of Economic Literature 46(4), 910-945.

Bloom, N., 2009, The impact of uncertainty shocks, Econometrica 77(3), 623-685.

Bloom, N., 2014, Fluctuations in uncertainty, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(2), 153-176.

Bloom, N., Floetotto, M., Jaimovich, N., Saporta‐Eksten, I., Terry, S. J., 2018, Really uncertain business cycles, Econometrica 86(3), 1031-1065.

Chang, B. Y., Feunou, B., 2013, Measuring uncertainty in monetary policy using implied volatility and realized volatility (No. 2013-37), Bank of Canada working paper.

Cho, D., Kim, H., 2023, Macroeconomic effects of uncertainty shocks: Evidence from Korea, Journal of Asian Economics 84, 101571.

Couture, C., 2021, Financial market effects of FOMC projections, Journal of Macroeconomics, 67, 103279.

Eberly, J. C., 1994, Adjustment of consumers' durables stocks: Evidence from automobile purchases, Journal of Political Economy 102(3), 403-436.

Husted, L., Rogers, J., Sun, B., 2020, Monetary policy uncertainty, Journal of Monetary Economics 115, 20-36.

Issing, O., 2005, Communication, transparency, accountability: monetary policy in the twenty-first century, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 87(2), 65-83.

Mishkin, F. S., 2004, Can Central Bank Transparency Go Too Far? NBER Working Paper (w10829).

Swanson, E. T., 2006, Have increases in Federal Reserve transparency improved private sector interest rate forecasts? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 791-819.

[Korean]

Jung, H.C., 2024, Characteristics and economic impact of domestic monetary policy uncertainty, Korea Capital Market Institute Issue Paper 24-09.

Table 1 presents the changes in the BOK Monetary Policy Board (MPB)’s outlook for the benchmark interest rate over a three-month horizon. Since October 2023, the number of MPB members advocating for a rate hike has decreased, and no views supporting interest rate rises have been presented this year. As a result, market concerns about further benchmark rate rises have diminished significantly, but uncertainty over the duration of the current monetary tightening and the timing and magnitude of potential rate cuts remains a persistent source of concern.

Expectations for a delay in US rate cuts also add to uncertainty regarding domestic monetary policy. Table 2 illustrates changes in the Fed members’ median projections for the US economic growth rate, inflation, and the federal funds rate on a year-on-year basis. The forecasts for inflation and the federal funds rate as of the end of this year, presented in December 2023, were revised down compared to the September 2023 forecasts, which raises expectations for the Fed’s rate cuts within 2024. However, the March 2024 forecasts for economic growth and the increase in the core PCE price index were adjusted upward compared to the December 2023 forecasts, reflecting a delayed slowdown in inflation and a stronger US economic recovery. Although the median forecast for the federal funds rate has remained unchanged, there has been an upward shift in the distribution of forecasts, delaying expectations for the Fed’s rate cuts and heightening uncertainty about their timing and magnitude. Notably, the Korea-US interest rate differential has reached an all-time high of 2% and the exchange rate between the two countries has remained elevated for an extended period. Consequently, expectations for delayed rate cuts in the US act as an additional constraint on the flexibility of Korea’s domestic monetary policy.

Despite a downward trend of inflation in South Korea, upside risks to domestic inflation have increased due to factors such as the recent surge in import prices spurred by high exchange rates, the rebound in expected inflation observed in May, rising producer prices, heightened exchange rate volatility, and geopolitical tensions. Furthermore, prolonged monetary tightening in the US and the record-high interest rate differential between Korea and the US are amplifying the ongoing uncertainty about the trajectory of domestic monetary policy.

Economic impacts of monetary policy uncertainty

Even if there is no direct change in the policy interest rate, heightened monetary policy uncertainty, as perceived in the private sector, can affect the decision-making of economic agents and investors. This uncertainty can potentially have adverse effects on both the real economy and capital markets. For example, the wait-and-see effect, a typical path for spreading uncertainty, suggests that increased economic uncertainty may postpone irreversible decisions such as business investments, employment, and durable goods consumption until uncertainty levels subside, thereby contracting the real economy (Bernanke, 1983; Bloom, 2009; Bloom, 2014; Eberly, 1994; Husted et al., 2020). In addition to the impact of worsening real economic conditions, such uncertainty can also negatively affect the capital markets by reducing investor participation.

Figure 1 shows how domestic real economic variables respond to heightened monetary policy uncertainty shocks2) on a monthly basis.3) The increase in domestic monetary policy uncertainty significantly curtails industrial production over a six-month period, whereas demonstrating no significant impact on inflation. In addition to weakening aggregate demand through the wait-and-see effect, increased uncertainty can reduce the input of production factors and lead to their misallocation, thereby contracting aggregate supply (Bloom et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that despite increased monetary policy uncertainty shocks to the market, changes in aggregate supply an demand seem to offset each other, resulting in negligible effects on prices.

Figure 2 shows how domestic financial market variables react to monetary policy uncertainty shocks in South Korea. The analysis indicates that such shocks markedly widen the credit spread between 3-year AA-rated corporate bonds and government bonds, decrease the KOSPI significantly, and boost the US dollar to the Korean won (USD/KRW) exchange rate. The uncertainty can lead to a deterioration in the real economy, thereby amplifying credit risk for companies. Moreover, increased uncertainty can discourage domestic and foreign investors from participating in the Korean capital market, resulting in an increase in risk premiums demanded by investors. In addition, it can escalate the risk of won-denominated assets compared to foreign currency-denominated assets, potentially contributing to the depreciation of the Korean won. The impact of increased monetary policy uncertainty on the financial market can be understood as a combination of deteriorating real economic conditions, as reflected in the financial market, and changes in investor behavior.

In summary, the analysis reveals that the escalation of monetary policy uncertainty in South Korea has an adverse impact on the real economy and capital markets, leading to a contraction in industrial production, increased corporate financing costs, and a decline in stock indices, and also can contribute to the depreciation of the Korean won. These findings suggest that the expansion and volatility of monetary policy uncertainty can undermine the stability of the Korean real economy and financial market.

BOK’s forward guidance and monetary policy uncertainty

Central bank communication plays a crucial role in facilitating economic agents’ understanding of how monetary policies are implemented and in enhancing the predictability of future monetary policy directions by providing various information to the public (Blinder et al., 2008). Therefore, communication from monetary authorities can serve as an effective policy tool to mitigate the uncertainty perceived by economic agents and reduce the associated social costs. For example, Swanson (2006) finds that enhanced communication by the US Fed considerably reduced forecast errors of the private sector regarding future policy interest rates. Similarly, Chang and Feunou (2013) show that uncertainty about future interest rates in Canada declined on average following the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy announcement.

Since October 2022, the BOK has expanded its communication to the public by presenting the distribution of MPB members’ projections for the future policy rate over a three-month horizon at the Governor’s press conference immediately following monetary policy direction meetings.4) This conditional forward guidance, which presents policy rate forecasts based on the current assessment of future economic conditions, can mitigate the information asymmetry between the central bank and the public. By providing previously unavailable information, it also enhances the predictability of future monetary policy directions for economic agents. It is noteworthy that economic agents may misunderstand conditional forecasts, which are based on multiple assumptions, as a commitment to future policies. In this case, the credibility of the central bank could be compromised if a rapid change in economic conditions necessitates a policy decision divergent from the current outlook on policy rates (Mishkin, 2004; Issing, 2005). Although the BOK’s adoption of conditional forward guidance seems to help alleviate monetary policy uncertainty until recently (Jung, 2024), the persistence of this effect remains uncertain, prompting consideration of the following improvements.

First, any significant changes in the distribution of forecasts or divergence in opinions among MPB members should be clearly explained through sufficient data. A substantial shift in the distribution of policy rate projections or widening divergence in interest rate forecasts can cause the financial market to react sensitively, even in the absence of a direct shift in the policy interest rate stance, which potentially makes it challenging for the market to predict monetary policy paths (Couture, 2021). In South Korea, since the introduction of conditional forward guidance, there has been neither a noticeable difference in terminal interest rate forecasts among MPB members nor a sudden change in the forecast distribution. However, if such a case occurs in the future, it could amplify the uncertainty perceived by economic agents regarding monetary policy stance. To mitigate unintended side effects, sophisticated communication tools should be implemented, such as providing clear explanations and sufficient data regarding changes in the forecast distribution or differences in opinions among MPB members.

Second, each MPB member may be required to present the rationale behind their benchmark rate projections. In the current system, the common rationale of the group of members proposing the same opinion (possibility of rate cuts or hikes, possibility of maintaining the current level) is mentioned at the press conference, along with the distribution of MPB members’ projections, but each member’s rationale is not provided. MPB members who share the same forecast opinion may differ in their underlying rationale and assumptions.5) Despite the conditional nature of MPB members’ benchmark rate projections, which rely on the current assessment of expected economic conditions, there is a lack of information about the specific assumptions each member uses to justify their projections. This limits the market’s understanding of how each member has arrived at their projections. It may also cause the market to focus more on the figures themselves rather than the underlying rationale, which could undermine the credibility of the monetary authorities if future policy directions divulge from the current projections. To ensure that conditional forward guidance facilitates the market’s understanding of how monetary authorities implement policies, rather than simply managing expectations for future interest rates, the rationale for each projection should be presented individually. Therefore, it is advisable to disseminate a summary of each MPB member’s rationale for benchmark rate projections as it would enhance the effectiveness of conditional forward guidance.

The BOK has indicated that it is internally discussing the possibility of extending the horizon of conditional forward guidance beyond the current three months (Governor’s press conference on monetary policy direction, February 22, 2024). As the time horizon lengthens, the uncertainty of projections and the potential for errors will increase. Without sufficient explanation and data regarding the assumptions or rationale behind projections, repeated forecast errors could damage the credibility of the monetary authorities and cause market confusion. Therefore, if the forward guidance horizon is extended, it will be crucial to implement the aforementioned improvement measures.

1) It suggests that there should be flexibility in either raising or lowering the benchmark interest rate over the next three months.

2) I use the news-based monetary policy uncertainty index in South Korea measured by Cho & Kim (2023). This monthly index is based on the frequency of monetary policy uncertainty-related articles from major newspapers in South Korea. A news-based index can comprehensively reflect uncertainty about various aspects of economic policy measures, including what policy decisions will be made, when they will be implemented, and how they will affect the economy (Baker et al., 2016). It can also capture the uncertainty perceived by a wide range of economic agents, provided that the media reflects the interests of a broad readership (Husted et al., 2020).

3) To estimate the economic impacts of monetary policy uncertainty shocks in South Korea, a structural vector autoregression model is estimated using sign restrictions. The model includes seven endogenous variables: the industrial production index, call rate, Korean monetary policy uncertainty index, credit spread between 3-year AA-rated corporate bonds and government bonds, KOSPI, and USD/KRW exchange rate. Additionally, the US monetary policy uncertainty index (Baker et al., 2016), the US stock market volatility index, and the federal funds rate are included as exogenous variables.

4) Central banks that provide projections for future policy rates include the US Federal Reserve, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Norges Bank, and the Riskbank. Regarding the provision of forecasts, they differ in terms of the introduction timing, the frequency and manner, and the time horizon.

5) These assumptions may include whether the opinion is based on common economic outlook data or incorporates additional individual economic projection models or data, and how they assess domestic and international economic uncertainties.

References

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., 2016, Measuring economic policy uncertainty, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4), 1593-1636.

Bernanke, B. S., 1983, Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 98(1), 85-106.

Blinder, A. S., Ehrmann, M., Fratzscher, M., De Haan, J., Jansen, D. J., 2008, Central bank communication and monetary policy: A survey of theory and evidence, Journal of Economic Literature 46(4), 910-945.

Bloom, N., 2009, The impact of uncertainty shocks, Econometrica 77(3), 623-685.

Bloom, N., 2014, Fluctuations in uncertainty, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(2), 153-176.

Bloom, N., Floetotto, M., Jaimovich, N., Saporta‐Eksten, I., Terry, S. J., 2018, Really uncertain business cycles, Econometrica 86(3), 1031-1065.

Chang, B. Y., Feunou, B., 2013, Measuring uncertainty in monetary policy using implied volatility and realized volatility (No. 2013-37), Bank of Canada working paper.

Cho, D., Kim, H., 2023, Macroeconomic effects of uncertainty shocks: Evidence from Korea, Journal of Asian Economics 84, 101571.

Couture, C., 2021, Financial market effects of FOMC projections, Journal of Macroeconomics, 67, 103279.

Eberly, J. C., 1994, Adjustment of consumers' durables stocks: Evidence from automobile purchases, Journal of Political Economy 102(3), 403-436.

Husted, L., Rogers, J., Sun, B., 2020, Monetary policy uncertainty, Journal of Monetary Economics 115, 20-36.

Issing, O., 2005, Communication, transparency, accountability: monetary policy in the twenty-first century, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 87(2), 65-83.

Mishkin, F. S., 2004, Can Central Bank Transparency Go Too Far? NBER Working Paper (w10829).

Swanson, E. T., 2006, Have increases in Federal Reserve transparency improved private sector interest rate forecasts? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 791-819.

[Korean]

Jung, H.C., 2024, Characteristics and economic impact of domestic monetary policy uncertainty, Korea Capital Market Institute Issue Paper 24-09.