OPINION

2019 Apr/09

Analysis of Reasons for Delisting and Korean Stock Market Integrity

Apr. 09, 2019

PDF

- Summary

- Delisting has been causing controversy these days. Delisting-related conflicts are likely to increase in the changing market environment where accounting firms are held more responsible for their audits and tighter substantive or qualitative delisting review is in place. It is time to find ways to reduce the delisting burden of companies and improve market integrity. Above all, appropriate exit routes should be provided to firms by revamping the market structure. Listed companies have three exit options to choose: leave stock exchanges and move to OTC markets, move to a less regulated market, or be sold to another company. None of the three choices, however, are readily available in the Korean market. Accordingly, it is necessary to come up with supplementary measures tailored to the country-specific circumstances, for example, revamping the regulated OTC market for distressed firms, supporting revival of delisted firms or smooth transfer to a lower-tier market with less stringent regulation and lower listing costs, and facilitating M&As for small innovative firms. In addition, persistent efforts are required for the exchange to gain market trust in its delisting decisions. Moreover, it should use coherent delisting criteria and provide sufficient grounds for its delisting decisions to companies and investors not to cause unnecessary controversy and market distrust. More importantly, efforts are necessary to reduce the burden of both the exchange and listed companies and to increase the reliability and integrity of the stock market.

Delisting controversy continues to swirl into 2019. Various issues emerged in 2018, such as suspicion of accounting breaches and debates on R&D accounting practices mainly in the pharmaceuticals and biotechnology sector. However, the delisting controversy arose not just last year but has been recurrent since Korea Exchange (KRX) was launched. The exchange’s decision to delist has been constantly challenged by the companies that were forcibly delisted, leading to legal disputes. To support the revival of companies in distress and improve the stock market integrity, we need to discuss delisting issues from a broader perspective. It is time to move away from a polarized debate between firms and the stock exchange from a micro perspective and to investigate reasons for delisting from a wider perspective and discuss what structural improvements should be made.

Current state of delistings

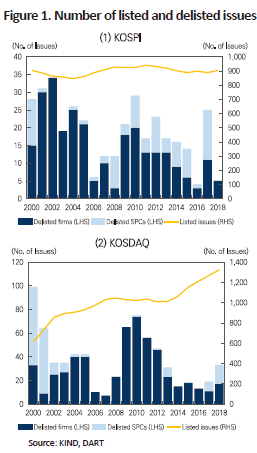

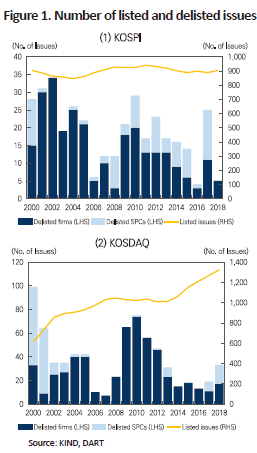

Delisting from the stock exchange in Korea has been affected substantially by economic crises such as the dotcom bubble burst or the 2008 global financial crisis. In most cases, a company does not face immediate delisting of its shares unless it is bankrupt or liquidated, but is designated as ‘administrative issues’. As a result, even if a material problem affecting the survival of the company occurs, a delisting move starts to be seen in the market after a certain period of time has lapsed. The number of delistings increased sharply over several years after the dotcom bubble burst in early 2000s. The same phenomenon occurred over a couple of years after the global financial crisis was triggered by the US subprime mortgage woes in 2008. From 2000 onwards, more than half of delistings took place within three years after the onset of the crises.

Over the past two decades, the regulatory rigor of formal and quantitative criteria for designating administrative issues and making delisting decisions has not changed significantly. In practice, newly introduced ‘comprehensive listing eligibility reviews’ have had impacts on delisting, contributing to identifying a number of bad firms that were not filtered through a formal delisting review. It is hard to conclude that this resulted only from the substantial review given its adoption in 2009 immediately after the global financial crisis broke out. But one thing is sure: the number of delistings soared after the introduction of the substantive review. It is noteworthy that the number of delistings as a result of substantive reviews in the KOSDAQ market was 14 in 2009 and rose two-fold to 28 in 2010. The substantive assessment scheme appears to have contributed to improving the integrity of the stock exchange by early removal of improperly-run companies.

Overall, however, the number of delistings in the domestic stock market is not large. For the period from 2000 to 2018, 361 issues were delisted from the KOSPI and 729 issues from the KOSDAQ. After excluding special purpose companies(SPCs) such as special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) and investment companies, the number of delistings becomes even smaller, with an average of only 43 companies a year, which is considerably low compared to those in the major exchanges in the US and Europe. According to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE), the number of firms delisted from the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and NASDAQ was 160 and 356, respectively, on average annually from 2000 to 2017. Meanwhile, 288 firms were delisted from the London Stock Exchange (LSE) each year.

Comparative analysis of reasons for delisting

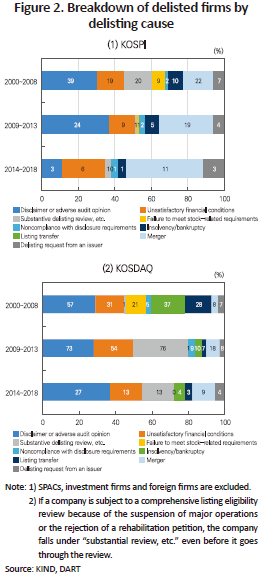

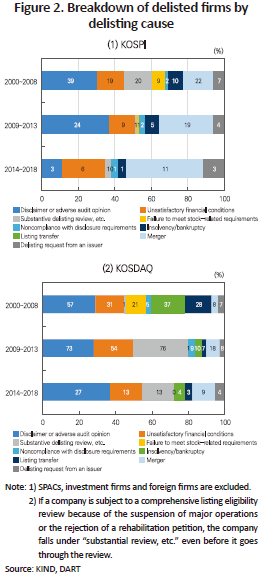

The investigation of the reasons for delisting over three periods reveal the following characteristics: First, M&A delistings and voluntary delistings grew more in both KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets. In the KOSPI market in particular, firms delisted either voluntarily or due to a merger represented more than half of delisted firms during the 2014-2018 period. Also in the KOSDAQ market, the proportion of voluntary delistings rose slightly, which is still lower than that in the KOSPI. Most mergers were aimed at reforming corporate governance, for example, through reorganization or amalgamation of subsidiaries in a business group or conversion of a holding company into a wholly owned subsidiary. Only seven companies were delisted for the other reasons during the 2014-2018 period, suggesting that Korean companies rarely chose to delist themselves voluntarily after taking into account the costs and benefits of a stock market listing. In other words, most companies tend to get delisted by the exchange when they fail to meet minimum continued listing requirements rather than voluntarily delist themselves.

Second, the proportion of firms that were delisted because they fell short of standards of audit reports increased in the KOSDAQ market. The exchange makes a decision to delist if a company receives a disclaimer, adverse or qualified opinion on its financial statements from its external auditor. In accordance with the Act on External Audit of Stock Companies which came into effect in November 2018, external auditors as well as companies will face penalties in the event of accounting fraud. As accounting firms are held more responsible for their audits, they tend to undertake audits in a more rigorous manner. Consequently, many listed firms recently faced delisting due to disclaimer or adverse audit opinions.

Third, stock listing transfers have occurred only from the KOSDAQ to the KOSPI, not the other way around. The KOSPI and the KOSDAQ are pursuing their development by competing with each other rather than structuring multi-tiered stock markets. It means that even if a company becomes difficult to maintain its listing on the KOSPI, the company are not selecting the KOSDAQ as an alternative market to transfer to. Not only that, there has been no transfer of stock listing to the KONEX. Although it is certainly a sub-market as compared to the two other markets in hierarchical grouping, distressed firms are avoiding listings transfer mainly because of restrictions on types of investors, inequalities in taxes and benefits, and sluggish transactions.

Structural limitations and regulatory environment

The current market structure presents few options open to a firm after it is delisted. If a listed company is unable to maintain its listing status in an established stock exchange, it can choose one of three exit routes: moving from the exchange to over-the-counter (OTC) markets, transferring its stock listing to a less regulated market, or selling itself to another company. In the US stock market, many OTC markets are operating actively and a company may continue trading even after the delisting of its shares in major exchanges such as NYSE or NASDAQ. In Korea, there are also OTC markets including K-OTC and K-OTCBB operated by Korea Financial Investment Association. But trading volumes in those OTC markets are not significant. Because most OTC trades occur through unregulated private websites or unregistered brokers, investors in OTC stocks are not given adequate investor protection.

Furthermore, it is not easy for a delisted firm to move to the lower-tier market with less stringent regulation and lower listing costs. In fact, there has been no listing transfer to a lower tier since the establishment of the stock exchange in Korea. By looking at the stock markets of Canada and the United Kingdom in which bi-directional listing transfers between markets are most active, we can infer the reasons for no listing transfer to the lower tier market in Korea. TMX in Canada operates multiple stock markets in an apparent hierarchical structure and specifies rules for movements between markets at different hierarchical levels. If a company fails to satisfy continued listing requirements in a higher tier market, it will be compulsorily transferred to a lower tier market or lower market section. If the company also falls below continued listing criteria for a stock market at the bottom of the hierarchy, it will be moved to NEX which is a market place for delisted firms. NEX appears to perform the role of an OTC market. In the meantime, companies in the UK have often chosen to voluntarily move their listing from one market to another due to lower listing costs and better benefits, not due to involuntary delisting. The Alternative Investment Market (AIM) is a less regulated market than the LSE’s main market and offers tax benefits including capital gains tax relief and inheritance tax relief to investors in AIM companies. Plenty of companies moved from the LSE to the AIM to save listing costs.

Korea has also two stock markets, the KOSPI and the KOSDAQ, which are subject to different levels of regulation and provide different benefits. But the differences between the two are not significant enough to induce companies to move from the KOSPI to the KOSDAQ in order to save listing and maintenance costs. Although there is the KONEX market, equivalent to the AIM, KOSPI or KOSDAQ-listed firms hesitate to switch their listing to the KONEX. The KONEX is also reluctant to play a similar role to Canada’s NEX due to concerns that the entry of distressed or delisted companies could worsen the market integrity.

Delisting via M&A is not an easy option. In an active M&A market, an unlisted or private innovative firm seeks a stock market listing to enhance its recognition and delists itself if it is successfully acquired by another firm. In spite of Korea’s continuing efforts to revitalize the M&A market and recent large-scale M&A deals in major sectors, it is difficult to tell that the market is dynamic enough to underpin vibrant M&A activity among small innovative companies.

In addition to the structural limitations of the market, the changes in the reasons for delisting indicate that controversy over delisting will continue. Among the reasons behind involuntary delisting, the proportion of criteria that require the judgement of those charged with an assessment of a firm has been on the rise. Good examples are a disclaimer or adverse opinion from an auditor and the comprehensive listing eligibility review by the exchange. As for disclaimer or adverse audit opinions unlike other explicit quantitative requirements, it is difficult for individual investors to predict audit results or gauge their severity level. With a recently growing number of companies in innovative industries such as the pharma and biotech industry where a one-size-fits-all approach is hardly applicable, accounting treatment becomes a frequent topic in debates among experts. More issues related to accounting treatment are expected to arise as the proportion of new technology and innovation industries increases.

Furthermore, a variety of issues have emerged in relation to strengthened accountability of accounting firms, including difficulty making an re-audit contract, excessive re-audit costs, and audit delays caused by forensic audit work. Competent authorities put in place supplementary measures to eliminate re-audit process and adopt delisting decision-making based on an auditor’s opinion on the financial statements of a company for the following year, in order to reduce market confusions and protect investors. Still, however, auditors are highly likely to be more proactive in expressing their disclaimer or qualified opinions.

Not only that, the comprehensive listing eligibility review by the exchange was tightened to early expel companies that commit misconduct. KRX has continued to lower barriers to entry for unlisted firms so as to support their growth. The most notable is the adoption of “Tesla standards,” which allows listing of promising companies that have not yet realized a profit. Since relaxed listing criteria could undermine investor trust in the stock market, KRX broadened the scope of companies subject to substantive or qualitative delisting review in tandem with the introduction of the new standards. The substantive review is a useful tool to weed out bad firms that are hardly detected by a formal or quantitative review. However, under the current scheme, a delisting decision is made by the exchange based on its own judgement about the continuity and financial stability of a company. Accordingly, delisting decisions are bound to create market resistance and controversy. This situation calls for efforts not to lose market participants’ trust in the exchange’s judgement and decision.

Need to improve market integrity by building better delisting environment

There are concerns that delisting will continue to stir up controversy. In the situation where firms in distress are difficult to choose to delist voluntarily, a delisting decision will weigh down on not only firms but also the exchange that decides on whether to force them to delist. The lack of available alternative exit routes causes distressed companies to remain listed on the exchange. In the end, many companies would have to stay in the market although they are in extreme financial distress. This would hinder the growth of listed companies and ultimately undermine the market integrity. Hence, it is necessary to strive for the creation of a market for smooth exit and revival of delisted firms and to make the structure of the stock market more flexible. Moreover, the exchange should use coherent principles in making delisting decisions in order to enhance confidence in the delisting decisions, and provide sufficient grounds for the delisting decisions to companies and investors. It is time to make every effort to reduce the burden of the exchange and listed companies and to increase the reliability and integrity of the stock market.

Current state of delistings

Delisting from the stock exchange in Korea has been affected substantially by economic crises such as the dotcom bubble burst or the 2008 global financial crisis. In most cases, a company does not face immediate delisting of its shares unless it is bankrupt or liquidated, but is designated as ‘administrative issues’. As a result, even if a material problem affecting the survival of the company occurs, a delisting move starts to be seen in the market after a certain period of time has lapsed. The number of delistings increased sharply over several years after the dotcom bubble burst in early 2000s. The same phenomenon occurred over a couple of years after the global financial crisis was triggered by the US subprime mortgage woes in 2008. From 2000 onwards, more than half of delistings took place within three years after the onset of the crises.

Overall, however, the number of delistings in the domestic stock market is not large. For the period from 2000 to 2018, 361 issues were delisted from the KOSPI and 729 issues from the KOSDAQ. After excluding special purpose companies(SPCs) such as special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) and investment companies, the number of delistings becomes even smaller, with an average of only 43 companies a year, which is considerably low compared to those in the major exchanges in the US and Europe. According to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE), the number of firms delisted from the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and NASDAQ was 160 and 356, respectively, on average annually from 2000 to 2017. Meanwhile, 288 firms were delisted from the London Stock Exchange (LSE) each year.

Comparative analysis of reasons for delisting

The investigation of the reasons for delisting over three periods reveal the following characteristics: First, M&A delistings and voluntary delistings grew more in both KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets. In the KOSPI market in particular, firms delisted either voluntarily or due to a merger represented more than half of delisted firms during the 2014-2018 period. Also in the KOSDAQ market, the proportion of voluntary delistings rose slightly, which is still lower than that in the KOSPI. Most mergers were aimed at reforming corporate governance, for example, through reorganization or amalgamation of subsidiaries in a business group or conversion of a holding company into a wholly owned subsidiary. Only seven companies were delisted for the other reasons during the 2014-2018 period, suggesting that Korean companies rarely chose to delist themselves voluntarily after taking into account the costs and benefits of a stock market listing. In other words, most companies tend to get delisted by the exchange when they fail to meet minimum continued listing requirements rather than voluntarily delist themselves.

Third, stock listing transfers have occurred only from the KOSDAQ to the KOSPI, not the other way around. The KOSPI and the KOSDAQ are pursuing their development by competing with each other rather than structuring multi-tiered stock markets. It means that even if a company becomes difficult to maintain its listing on the KOSPI, the company are not selecting the KOSDAQ as an alternative market to transfer to. Not only that, there has been no transfer of stock listing to the KONEX. Although it is certainly a sub-market as compared to the two other markets in hierarchical grouping, distressed firms are avoiding listings transfer mainly because of restrictions on types of investors, inequalities in taxes and benefits, and sluggish transactions.

Structural limitations and regulatory environment

The current market structure presents few options open to a firm after it is delisted. If a listed company is unable to maintain its listing status in an established stock exchange, it can choose one of three exit routes: moving from the exchange to over-the-counter (OTC) markets, transferring its stock listing to a less regulated market, or selling itself to another company. In the US stock market, many OTC markets are operating actively and a company may continue trading even after the delisting of its shares in major exchanges such as NYSE or NASDAQ. In Korea, there are also OTC markets including K-OTC and K-OTCBB operated by Korea Financial Investment Association. But trading volumes in those OTC markets are not significant. Because most OTC trades occur through unregulated private websites or unregistered brokers, investors in OTC stocks are not given adequate investor protection.

Furthermore, it is not easy for a delisted firm to move to the lower-tier market with less stringent regulation and lower listing costs. In fact, there has been no listing transfer to a lower tier since the establishment of the stock exchange in Korea. By looking at the stock markets of Canada and the United Kingdom in which bi-directional listing transfers between markets are most active, we can infer the reasons for no listing transfer to the lower tier market in Korea. TMX in Canada operates multiple stock markets in an apparent hierarchical structure and specifies rules for movements between markets at different hierarchical levels. If a company fails to satisfy continued listing requirements in a higher tier market, it will be compulsorily transferred to a lower tier market or lower market section. If the company also falls below continued listing criteria for a stock market at the bottom of the hierarchy, it will be moved to NEX which is a market place for delisted firms. NEX appears to perform the role of an OTC market. In the meantime, companies in the UK have often chosen to voluntarily move their listing from one market to another due to lower listing costs and better benefits, not due to involuntary delisting. The Alternative Investment Market (AIM) is a less regulated market than the LSE’s main market and offers tax benefits including capital gains tax relief and inheritance tax relief to investors in AIM companies. Plenty of companies moved from the LSE to the AIM to save listing costs.

Korea has also two stock markets, the KOSPI and the KOSDAQ, which are subject to different levels of regulation and provide different benefits. But the differences between the two are not significant enough to induce companies to move from the KOSPI to the KOSDAQ in order to save listing and maintenance costs. Although there is the KONEX market, equivalent to the AIM, KOSPI or KOSDAQ-listed firms hesitate to switch their listing to the KONEX. The KONEX is also reluctant to play a similar role to Canada’s NEX due to concerns that the entry of distressed or delisted companies could worsen the market integrity.

Delisting via M&A is not an easy option. In an active M&A market, an unlisted or private innovative firm seeks a stock market listing to enhance its recognition and delists itself if it is successfully acquired by another firm. In spite of Korea’s continuing efforts to revitalize the M&A market and recent large-scale M&A deals in major sectors, it is difficult to tell that the market is dynamic enough to underpin vibrant M&A activity among small innovative companies.

In addition to the structural limitations of the market, the changes in the reasons for delisting indicate that controversy over delisting will continue. Among the reasons behind involuntary delisting, the proportion of criteria that require the judgement of those charged with an assessment of a firm has been on the rise. Good examples are a disclaimer or adverse opinion from an auditor and the comprehensive listing eligibility review by the exchange. As for disclaimer or adverse audit opinions unlike other explicit quantitative requirements, it is difficult for individual investors to predict audit results or gauge their severity level. With a recently growing number of companies in innovative industries such as the pharma and biotech industry where a one-size-fits-all approach is hardly applicable, accounting treatment becomes a frequent topic in debates among experts. More issues related to accounting treatment are expected to arise as the proportion of new technology and innovation industries increases.

Furthermore, a variety of issues have emerged in relation to strengthened accountability of accounting firms, including difficulty making an re-audit contract, excessive re-audit costs, and audit delays caused by forensic audit work. Competent authorities put in place supplementary measures to eliminate re-audit process and adopt delisting decision-making based on an auditor’s opinion on the financial statements of a company for the following year, in order to reduce market confusions and protect investors. Still, however, auditors are highly likely to be more proactive in expressing their disclaimer or qualified opinions.

Not only that, the comprehensive listing eligibility review by the exchange was tightened to early expel companies that commit misconduct. KRX has continued to lower barriers to entry for unlisted firms so as to support their growth. The most notable is the adoption of “Tesla standards,” which allows listing of promising companies that have not yet realized a profit. Since relaxed listing criteria could undermine investor trust in the stock market, KRX broadened the scope of companies subject to substantive or qualitative delisting review in tandem with the introduction of the new standards. The substantive review is a useful tool to weed out bad firms that are hardly detected by a formal or quantitative review. However, under the current scheme, a delisting decision is made by the exchange based on its own judgement about the continuity and financial stability of a company. Accordingly, delisting decisions are bound to create market resistance and controversy. This situation calls for efforts not to lose market participants’ trust in the exchange’s judgement and decision.

Need to improve market integrity by building better delisting environment

There are concerns that delisting will continue to stir up controversy. In the situation where firms in distress are difficult to choose to delist voluntarily, a delisting decision will weigh down on not only firms but also the exchange that decides on whether to force them to delist. The lack of available alternative exit routes causes distressed companies to remain listed on the exchange. In the end, many companies would have to stay in the market although they are in extreme financial distress. This would hinder the growth of listed companies and ultimately undermine the market integrity. Hence, it is necessary to strive for the creation of a market for smooth exit and revival of delisted firms and to make the structure of the stock market more flexible. Moreover, the exchange should use coherent principles in making delisting decisions in order to enhance confidence in the delisting decisions, and provide sufficient grounds for the delisting decisions to companies and investors. It is time to make every effort to reduce the burden of the exchange and listed companies and to increase the reliability and integrity of the stock market.