Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Korea’s Financial Support Package to Small Merchants and Self-employed Under Covid-19

Publication date Apr. 09, 2020

Summary

As financial market unease continues and the real economy contracts seriously, Korea’s policy authorities have been stepping up their efforts to better cope with the Covid-19 pandemic. In particular, Korea unveiled a KRW 58.3 trillion financial support package with an aim to give support to small merchants and the self-employed that are bearing the biggest brunt of Covid-19. However, the package has two potential issues. First, it could possibly lead to excessive debt of the borrowers under the package. Second, the time lag of the loan provision process could make it harder for the borrowers to meet their imminent need for cash. To cope with those issues, supplementary actions are desired. What’s worth considering is to create an incentive for those implementing the package to become proactive to distribute funds. This could be done only under clear policy principles where the funds are distributed and managed under a separate account and any loss from that account is borne by fiscal support unless the loss arises from any intention or malfeasance. Also necessary is a detailed adjustment in policy. To prevent the funds provided by the package from adding a further repayment burden to the borrowers, it’s necessary to allow them to repay the debt through installments for over five years or so at the current low interest rate. On top of that, a policy tool to ease the borrower’s repayment burden may be needed to tackle potential side effects where the current package targeting already debt-ridden small merchants and the self-employed could just defer today’s economic hardships into the future. More concretely, it’s worth mulling over offering fiscal support to help the borrowers to pay rents or wages if they keep their workers employed despite a sales decline.

1. Financial support to small merchants and the self-employed

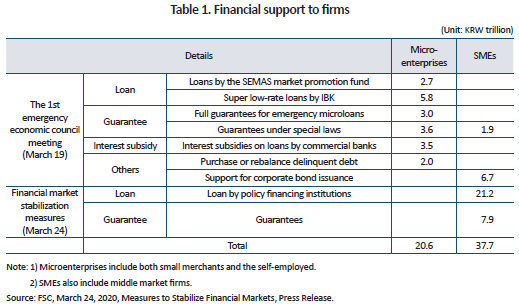

Korea’s government rolled out a financial support package worth KRW 58.3 trillion in its bid to help businesses to cope with their immediate liquidity needs under the Covid-19 pandemic. In its first round of emergency economic council meeting on March 19, the government had unveiled its first round of financial package worth KRW 29.2 trillion for small merchants, the self-employed, and SMEs. That was quickly followed on March 24 by another pledge for a KRW 29.2 trillion package to broaden the policy target into middle market firms as well. Those packages are expected to come from fiscal support, public guarantee providers, and state-owned and private sector banks.

Microenterprises who have been particularly hit hard by Covid-19 will receive a total of KRW 20.6 trillion, which includes loans worth KRW 2.7 trillion by SEMAS’s market promotion fund and KRW 5.8 trillion by the Industrial Bank of Korea. Also, bank loans will be backed by KRW 6.6 trillion guarantees by the regional credit guarantee foundations, the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund, and Korea Technology Finance Corporation. On top of that, another KRW 3.5 trillion will be injected to compensate the losses private sector banks will have from the low-rate loan package to microenterprises. Also, KRW 2 trillion will be used to purchase or rebalance delinquent debt held by microenterprises.

Such financial support is also supplemented by fiscal policies. The government will reduce or defer some of the national and local taxes, with the extended tax deadline. Also, tax deduction up to 50% will be applied to a landlord who cuts rent. However, fiscal support is incomparable to financial support in terms of the range and size.

2. Shortfalls in loan-based support

The aforementioned financial support is primarily driven by more loans based on further credits and guarantees, but there lie two potential shortfalls. First, more debt will impose a higher burden on small merchants and the self-employed, which could in the long run lead to problems from excessive debt. Second, the time lag between the announcement and the actual implementation of the package will make it hard for the targeted borrowers to meet their immediate liquidity needs.

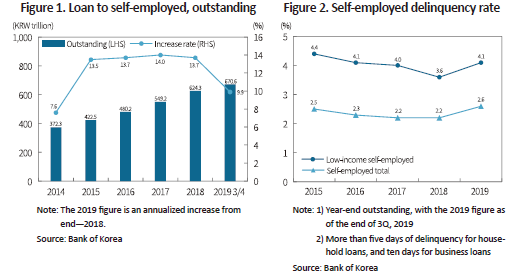

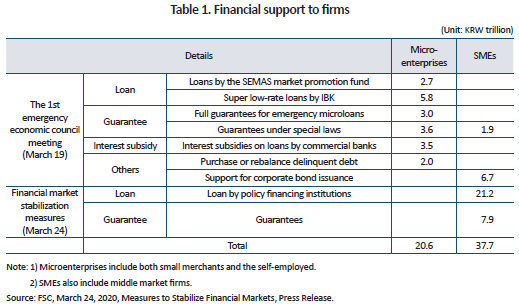

First, debt in small merchants and the self-employed is already at a significant level. Any policy to add more debt, albeit its exceptionally low interest rate of 1.5%, could be onerous in the long run because this too should be paid back at some point in time. According to the Bank of Korea (2019),1) the outstanding amount of loans to the self-employed reached KRW 671 trillion in end-September 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 13% for the past five years after 2015. This is quite fast-paced given that Korea’s nominal growth rate on annual average during the same period hovered around 4%. Although policy authorities’ strong measures in this area such as a loan review guideline could effectively curbed the steep increase as well as the delinquency rate, the self-employed are still highly indebted: The ratio of financial debt to current income among the indebted self-employed stood at 230% in 2018, with their debt service ratio reaching 39%. Also concerning is the structural vulnerability in some areas. Among the total debt held by the self-employed, about 25%2) is held by those with KRW 30 million or less income who are especially vulnerable to external shocks. Furthermore, most of those are food, beverage and other retailers who are already suffering from chronic financial difficulties due to cut-throat competition and low productivity. The delinquency rate of the self-employed had been steady before rising again in 2019. In particular, the figure has remained in the 4% range among low-income self-employed borrowers.

With the debt burden already at a significant level, an additional supply of loans worth over KRW 20 trillion will surely help small merchants and the self-employed to weather the imminent difficulties from covid-19 in the short run. But in the long run, it’s possible that this could worsen the burden of the already debt-stricken borrowers. In principle, liquidity-based financial support is purposed to provide emergency funds to a firm that has no solvency issue but is on the verge of default due to a temporary liquidity shortage. Ideally, once the firm successfully weathers the liquidity crisis thanks to the support, it will be able to repay the debt using its cash flows from normal business operations. Simply put, emergency liquidity should be provided only on the premise that the targeted borrower will be able to bear the burden of repayment in the future. However, this is not the case of most small merchants and the self-employed at issue. Most of them have uncertain cash flow prospects, with some of them already being excessively indebted. Without any measure to overcome the issue, it’s possible the borrowers to face with bigger difficulties in the future.

Another shortfall in loan-based financial support is the considerable time lag between the announcement, the actual implementation, and policy effects. It’s been already three months since the economic slump triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic put small merchants and the self-employed into immense financial hardships. What’s the most important to achieve intended policy objectives is supplying liquidity in a timely manner. Despite policy authorities’ all-out effort to push for the package to be implemented immediately, it will take a considerable amount of time before the implementation given the incentive structure faced by state-run banks, guarantee providers, and other institutions that are working on to implement the package. The market already has raised criticism on the belatedness of the package. Any loan provision process involves a review on the borrower’s repayment ability for managing credit risk, and the process cannot be skipped even in an emergency loan supported by policy authorities. Hence, it takes a considerable amount of time for a firm to apply for a loan and finally receive money in hand.

Of course, policy authorities have fully recognized this and currently been working hard on shortening the time lag, e.g., by directly providing fiscal support under relaxed loan conditions, or by increasing the guarantee rate, etc. Even so, it’s impossible to avoid the possibility of any loss from those loans, which will eventually add a further burden to policy authorities and guarantee providers. Under the circumstances, the absence of clear government principles on who’s responsible for what will only make the institutions implementing the package timid in their response to the need for fast loan provision.

3. Supplementary actions for enhancing policy effects

It’s advisable that some supplementary actions are needed to rapidly provide massive loans while minimizing the potential adverse effects in the future. Among others, incentives should be provided to encourage policy financing institutions and guarantee providers to be more proactive to speed up their loan approval process and to provide funds as fast as they can. An idea is to put funds to be provided under the package into a separate account under a clear principle where any loss arising from this account will be borne by the government unless the loss arises from any intention or malfeasance. By doing so, the institutions under the package could work more aggressively on providing funds without having to worry about being held accountable for every loss. To curb potential adverse effects where emergency loans could impose an excessive burden, additional assistance is necessary, e.g., allowing the borrowers to repay the debt through installments over five years or longer at the current low interest rate.

For small merchants and the self-employed with grim business prospects, financial support that should be repaid has a limited impact of just deferring today’s hardships into the future. With this regard, the government should consider sharing part of their fixed costs. A survey conducted by the Korea Labor Institute3) reported that operating expenses of the self-employed consist of material purchases (61.8%), labor costs (23.8%), rents (7.4%), credit card processing fees (1.9%), and utility bills (2.7%). Among those, rents are one of the fixed costs that are unavoidable even when the sales plunge drastically. Also problematic is the labor cost: Although it’s not a fixed cost, the labor cost is hardly manageable within a short period of time in response to a sales decline. Hence, rents and labor costs combined could form a considerable burden amid the Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant economic hardships. Against the backdrop, it’s recommended that the government carefully mull over a direct policy tool aiming to ease the cost burden on small merchants and the self-employed. More concretely, it’s worth considering a fiscal support package that helps them to pay rents or wages if they keep their business in operation and workers employed despite a sales decrease.

1) Bank of Korea, December 2019, Financial Stability Report.

2) In terms of the number of tenants

3) Hong, M.K., 2019, A survey on the self-employed, KLI Monthly Labor Review June 2019 (7-18).

Korea’s government rolled out a financial support package worth KRW 58.3 trillion in its bid to help businesses to cope with their immediate liquidity needs under the Covid-19 pandemic. In its first round of emergency economic council meeting on March 19, the government had unveiled its first round of financial package worth KRW 29.2 trillion for small merchants, the self-employed, and SMEs. That was quickly followed on March 24 by another pledge for a KRW 29.2 trillion package to broaden the policy target into middle market firms as well. Those packages are expected to come from fiscal support, public guarantee providers, and state-owned and private sector banks.

Microenterprises who have been particularly hit hard by Covid-19 will receive a total of KRW 20.6 trillion, which includes loans worth KRW 2.7 trillion by SEMAS’s market promotion fund and KRW 5.8 trillion by the Industrial Bank of Korea. Also, bank loans will be backed by KRW 6.6 trillion guarantees by the regional credit guarantee foundations, the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund, and Korea Technology Finance Corporation. On top of that, another KRW 3.5 trillion will be injected to compensate the losses private sector banks will have from the low-rate loan package to microenterprises. Also, KRW 2 trillion will be used to purchase or rebalance delinquent debt held by microenterprises.

Such financial support is also supplemented by fiscal policies. The government will reduce or defer some of the national and local taxes, with the extended tax deadline. Also, tax deduction up to 50% will be applied to a landlord who cuts rent. However, fiscal support is incomparable to financial support in terms of the range and size.

2. Shortfalls in loan-based support

The aforementioned financial support is primarily driven by more loans based on further credits and guarantees, but there lie two potential shortfalls. First, more debt will impose a higher burden on small merchants and the self-employed, which could in the long run lead to problems from excessive debt. Second, the time lag between the announcement and the actual implementation of the package will make it hard for the targeted borrowers to meet their immediate liquidity needs.

First, debt in small merchants and the self-employed is already at a significant level. Any policy to add more debt, albeit its exceptionally low interest rate of 1.5%, could be onerous in the long run because this too should be paid back at some point in time. According to the Bank of Korea (2019),1) the outstanding amount of loans to the self-employed reached KRW 671 trillion in end-September 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 13% for the past five years after 2015. This is quite fast-paced given that Korea’s nominal growth rate on annual average during the same period hovered around 4%. Although policy authorities’ strong measures in this area such as a loan review guideline could effectively curbed the steep increase as well as the delinquency rate, the self-employed are still highly indebted: The ratio of financial debt to current income among the indebted self-employed stood at 230% in 2018, with their debt service ratio reaching 39%. Also concerning is the structural vulnerability in some areas. Among the total debt held by the self-employed, about 25%2) is held by those with KRW 30 million or less income who are especially vulnerable to external shocks. Furthermore, most of those are food, beverage and other retailers who are already suffering from chronic financial difficulties due to cut-throat competition and low productivity. The delinquency rate of the self-employed had been steady before rising again in 2019. In particular, the figure has remained in the 4% range among low-income self-employed borrowers.

Another shortfall in loan-based financial support is the considerable time lag between the announcement, the actual implementation, and policy effects. It’s been already three months since the economic slump triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic put small merchants and the self-employed into immense financial hardships. What’s the most important to achieve intended policy objectives is supplying liquidity in a timely manner. Despite policy authorities’ all-out effort to push for the package to be implemented immediately, it will take a considerable amount of time before the implementation given the incentive structure faced by state-run banks, guarantee providers, and other institutions that are working on to implement the package. The market already has raised criticism on the belatedness of the package. Any loan provision process involves a review on the borrower’s repayment ability for managing credit risk, and the process cannot be skipped even in an emergency loan supported by policy authorities. Hence, it takes a considerable amount of time for a firm to apply for a loan and finally receive money in hand.

Of course, policy authorities have fully recognized this and currently been working hard on shortening the time lag, e.g., by directly providing fiscal support under relaxed loan conditions, or by increasing the guarantee rate, etc. Even so, it’s impossible to avoid the possibility of any loss from those loans, which will eventually add a further burden to policy authorities and guarantee providers. Under the circumstances, the absence of clear government principles on who’s responsible for what will only make the institutions implementing the package timid in their response to the need for fast loan provision.

3. Supplementary actions for enhancing policy effects

It’s advisable that some supplementary actions are needed to rapidly provide massive loans while minimizing the potential adverse effects in the future. Among others, incentives should be provided to encourage policy financing institutions and guarantee providers to be more proactive to speed up their loan approval process and to provide funds as fast as they can. An idea is to put funds to be provided under the package into a separate account under a clear principle where any loss arising from this account will be borne by the government unless the loss arises from any intention or malfeasance. By doing so, the institutions under the package could work more aggressively on providing funds without having to worry about being held accountable for every loss. To curb potential adverse effects where emergency loans could impose an excessive burden, additional assistance is necessary, e.g., allowing the borrowers to repay the debt through installments over five years or longer at the current low interest rate.

For small merchants and the self-employed with grim business prospects, financial support that should be repaid has a limited impact of just deferring today’s hardships into the future. With this regard, the government should consider sharing part of their fixed costs. A survey conducted by the Korea Labor Institute3) reported that operating expenses of the self-employed consist of material purchases (61.8%), labor costs (23.8%), rents (7.4%), credit card processing fees (1.9%), and utility bills (2.7%). Among those, rents are one of the fixed costs that are unavoidable even when the sales plunge drastically. Also problematic is the labor cost: Although it’s not a fixed cost, the labor cost is hardly manageable within a short period of time in response to a sales decline. Hence, rents and labor costs combined could form a considerable burden amid the Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant economic hardships. Against the backdrop, it’s recommended that the government carefully mull over a direct policy tool aiming to ease the cost burden on small merchants and the self-employed. More concretely, it’s worth considering a fiscal support package that helps them to pay rents or wages if they keep their business in operation and workers employed despite a sales decrease.

1) Bank of Korea, December 2019, Financial Stability Report.

2) In terms of the number of tenants

3) Hong, M.K., 2019, A survey on the self-employed, KLI Monthly Labor Review June 2019 (7-18).