Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Discussions on Unicorn Valuation and Implications

Publication date Jul. 07, 2020

Summary

Some of listed unicorns have failed to generate profits for a considerable time being, and this is well reflected in their lackluster share prices. Under this context, doubts have been raised about startup valuation and a possible overvaluation in the private market. A startup could be valued differently in the private and public markets primarily due to several factors such as short-termism of public market investors, a potential overvaluation if startup valuation meets with abundant liquidity in the global venture capital market, and lack of transparency in governance and accounting.

Startups too are supposed to generate profits as a profit-seeking company. In particular, a startup that once entered the public market should be able to turn around to profits and generate cash flows as fast as possible. Given that abundant liquidity in the private market likely leads to an overvaluation, cautious and cool-headed approach is needed to prevent the government’s venture nurturing policy from giving rise to fake unicorns that cannot generate actual cash flows. The current Covid-19 pandemic is expected to offer an opportunity via which overpriced unicorns in the global venture market come to the fore to get revaluated.

Startups too are supposed to generate profits as a profit-seeking company. In particular, a startup that once entered the public market should be able to turn around to profits and generate cash flows as fast as possible. Given that abundant liquidity in the private market likely leads to an overvaluation, cautious and cool-headed approach is needed to prevent the government’s venture nurturing policy from giving rise to fake unicorns that cannot generate actual cash flows. The current Covid-19 pandemic is expected to offer an opportunity via which overpriced unicorns in the global venture market come to the fore to get revaluated.

A unicorn means an unlisted startup firm whose value is $1 billion or higher. This term now symbolizes a successful startup company.1) All startup founders make their utmost effort in the hope that their businesses join ranks of unicorns as fast as possible. That ardent desire is often reflected in government policy goals that set out a plan to nurture a targeted number of unicorns within a set timeframe.2)

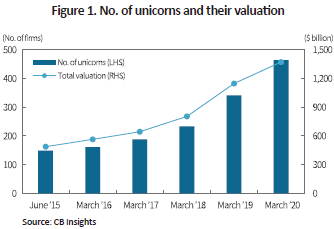

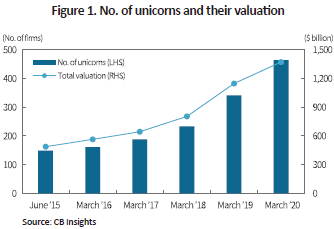

Globally, the number of unicorns has been on the steady rise, and the trend became particularly evident after 2018. As shown in Figure 1 based on CB Insights data, the number of unicorns stood at 149 in June 2016, but increased to 233 in March 2018 and 341 in March 2019, and finally to 464 in March 2020.3) Their combined firm value also rose steeply to reach $1.4 trillion as of March 2020.

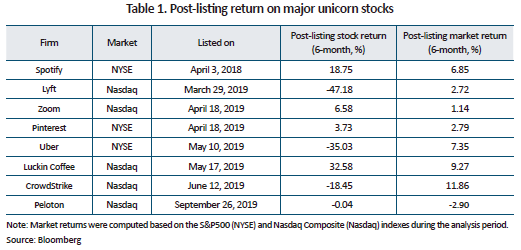

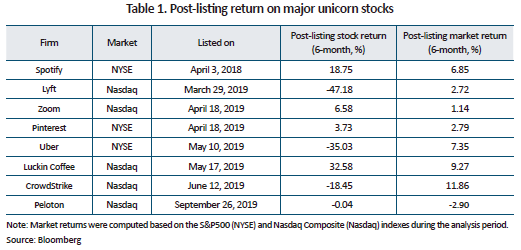

However, a significant number of unicorns who entered the public stock market via direct listing or IPO failed to generate positive cash flows as they had no profits out of their core businesses although they inject a massive amount of cash in investments and expenses. That seems to be well reflected to lackluster post-listing performance of some stocks. In worse cases, post-listing market capitalization of few firms went below their pre-listing valuation. Table 1 shows stock returns of major unicorns listed since 2018: their returns for six-month after listing were compared with market returns during the same period. For six-month after listing, car sharing service operators such as Uber and Lyft recorded extremely low returns of –35.03% and –47.18%, respectively, far lower than positive market returns during the respective period. A more extreme case was WeWork that completely scrapped its IPO plan. It is against the backdrop that doubts have been raised about startup valuation and possible overvaluation in the private market.4)

Presumably, there could be a few possibilities behind the phenomenon where firms highly valued in the private market were viewed differently in the public market. First, private market investors such as venture capitalists are professional, long-term investors who value long-term growth potential over short-term cash flows. They highly value firms with a business model that will potentially generate a significantly large amount of profits although the success rate is quite low. By contrast, public market investors have a shorter investor horizon than private market investors do. Hence, they are more likely to prioritize visible cash-generating abilities over other potentials. Firms such as Uber and Lyft have failed to post profits since their listing in the public market. This has immense implications for Korea: Korean investors, too, are likely to turn their back on startups that failed to report profits after they had only managed to enter the public market thanks to the loosening of listing requirements.

Second, there’s a possibility of overvaluation because of limitations inherent in the way firm value is evaluated and disclosed in the private market. In general, the reported valuation of an unlisted startup is determined when external investors such as venture capital carry out investment. In a simplified example, a startup owned 100% by its founder may receive a $2 million investment from venture capital in exchange for offering a 20% stake, which makes the firm’s reported valuation as high as $10 million. Entrepreneurs who want their startup to become a unicorn may do whatever they can for attracting investment, whereas investors who want a safety cushion against their risk may receive convertible or redeemable convertible preferred shares, whose claim structure vary across the series of investment.5) However, the way firms are currently valued doesn’t take into account the type of shares that come with different structure of claims.6)

On another front, abundant liquidity in the global venture capital market has been cited as another factor behind the overvaluation of startups. The size of dry power in the market steeply rose from $146 billion at the end of 2016 to $243 billion at the end of 2018.7) This makes it harder for venture capital to search for investment targets, whereas it’s less difficult for startups to attract investment. Fierce competition for investment could give rise to a potential overpricing in the process of firm valuation.8)9)

Certainly, investors would capitalize on their expertise and exert their utmost effort in distinguishing promising startups from those with less or no potential, and there might be only slim chances of startups seeing their value go over $1 billion. However, there are some reported cases that are casting doubt on the expertise of private market investors who are supposed to discern promising startups.10) Also negative on firm valuation in the public market is lack of transparency in governance and accounting: Many startups grant disproportionate voting rights to the founder, and some firms such as Luckin Coffee were caught in an accounting scandal.11)

What’s discussed above provides a few implications for the ecosystem of startups and venture capital, and relevant policy. First, startups are also a private company that is supposed to generate profits. The fundamental value of a firm is defined as the present value of cash flows the firm is expected to create in the future. However, it’s inevitable for a newly established firm to record a loss for some time being. This is particularly true in the case of the recent business environment where startups often choose to prioritize expansion over today’s profits, injecting large-scale capital with an aim to secure higher market share as fast as possible for benefiting from the network effect. However, such a situation could be something unbearable for public market investors, in particular trader-like investors with a relatively shorter investment horizon. Startups, once listed for trading on a public market, should be able to turn around to profits and generate cash flows as fast as possible.

As mentioned above, the way unlisted startups are valuated under the current practice is ripe for a valuation bubble as an excessive amount of capital sits and wait to be invested, making the competition for investment much fiercer than the one for attracting investment. This also holds true when the public sector invests risk capital in startups under the government’s policy drive for nurturing innovative venture firms. Cautious, cool-headed approach is required as too much emphasis on outcomes such as the number of unicorns may only give rise to fake unicorns that are actually unable to create cash flows.

When the economy is faced with a crisis, the bubble bursts and overvaluation gets adjusted. Although the Covid-19 pandemic can possibly pose a serious threat to both overpriced and sound firms, this, on the flip side, is expected to offer an opportunity via which overpriced unicorns come to the fore and get reasonably revaluated in the global venture market.

1) The term unicorn was first coined by US venture capitalist Aileen Lee in 2013.

2) Ministry of SMEs and Startups, April 9, 2020, Rising to world’s venture capital powerhouse: K-Unicorn Project, Press Release.

3) Among 464 unicorns, only ten firms are from Korea.

4) For example, refer to “The unicorn bubble is bursting” (Forbes, October 7, 2019).

Gornall and Strebulaev (2020) showed that the reported valuation of unicorns is 48% higher than the fair value on average (Gornall, W. Strebulaev, I. A., 2020, Squaring venture capital valuations with reality, Journal of Financial Economics 135, 120-143).

5) Shares such as convertible preferred shares are senior to common shares. This limits or sometimes completely eliminates the founder’s share of profits if the firm value turns below a certain level at the time of investment exit via IPO or M&A.

6) According to Gornall and Strebulaev (2020), a unicorn on average issues eight classes of shares.

7) Preqin, Global venture capital perspectives: A Preqin & Vertex Study.

8) Economist, April 4, 2020, Exit unicorns, pursued by bears.

9) It’s possible for private market investors to invest in startups because they expect IPO to help transfer their risk to public market investors (Forbes, October 7, 2019).

10) For example, WeWork is regarded as an investment failure for SoftBank Vision Fund.

11) When Luckin Coffee got mired in an accounting fraud and declared default, its shares dipped from $26.2 on April 1, 2020 to $6.4 the next day.

12) “Blitzscaling” was coined to refer to such a strategy.

Globally, the number of unicorns has been on the steady rise, and the trend became particularly evident after 2018. As shown in Figure 1 based on CB Insights data, the number of unicorns stood at 149 in June 2016, but increased to 233 in March 2018 and 341 in March 2019, and finally to 464 in March 2020.3) Their combined firm value also rose steeply to reach $1.4 trillion as of March 2020.

Second, there’s a possibility of overvaluation because of limitations inherent in the way firm value is evaluated and disclosed in the private market. In general, the reported valuation of an unlisted startup is determined when external investors such as venture capital carry out investment. In a simplified example, a startup owned 100% by its founder may receive a $2 million investment from venture capital in exchange for offering a 20% stake, which makes the firm’s reported valuation as high as $10 million. Entrepreneurs who want their startup to become a unicorn may do whatever they can for attracting investment, whereas investors who want a safety cushion against their risk may receive convertible or redeemable convertible preferred shares, whose claim structure vary across the series of investment.5) However, the way firms are currently valued doesn’t take into account the type of shares that come with different structure of claims.6)

On another front, abundant liquidity in the global venture capital market has been cited as another factor behind the overvaluation of startups. The size of dry power in the market steeply rose from $146 billion at the end of 2016 to $243 billion at the end of 2018.7) This makes it harder for venture capital to search for investment targets, whereas it’s less difficult for startups to attract investment. Fierce competition for investment could give rise to a potential overpricing in the process of firm valuation.8)9)

Certainly, investors would capitalize on their expertise and exert their utmost effort in distinguishing promising startups from those with less or no potential, and there might be only slim chances of startups seeing their value go over $1 billion. However, there are some reported cases that are casting doubt on the expertise of private market investors who are supposed to discern promising startups.10) Also negative on firm valuation in the public market is lack of transparency in governance and accounting: Many startups grant disproportionate voting rights to the founder, and some firms such as Luckin Coffee were caught in an accounting scandal.11)

What’s discussed above provides a few implications for the ecosystem of startups and venture capital, and relevant policy. First, startups are also a private company that is supposed to generate profits. The fundamental value of a firm is defined as the present value of cash flows the firm is expected to create in the future. However, it’s inevitable for a newly established firm to record a loss for some time being. This is particularly true in the case of the recent business environment where startups often choose to prioritize expansion over today’s profits, injecting large-scale capital with an aim to secure higher market share as fast as possible for benefiting from the network effect. However, such a situation could be something unbearable for public market investors, in particular trader-like investors with a relatively shorter investment horizon. Startups, once listed for trading on a public market, should be able to turn around to profits and generate cash flows as fast as possible.

As mentioned above, the way unlisted startups are valuated under the current practice is ripe for a valuation bubble as an excessive amount of capital sits and wait to be invested, making the competition for investment much fiercer than the one for attracting investment. This also holds true when the public sector invests risk capital in startups under the government’s policy drive for nurturing innovative venture firms. Cautious, cool-headed approach is required as too much emphasis on outcomes such as the number of unicorns may only give rise to fake unicorns that are actually unable to create cash flows.

When the economy is faced with a crisis, the bubble bursts and overvaluation gets adjusted. Although the Covid-19 pandemic can possibly pose a serious threat to both overpriced and sound firms, this, on the flip side, is expected to offer an opportunity via which overpriced unicorns come to the fore and get reasonably revaluated in the global venture market.

1) The term unicorn was first coined by US venture capitalist Aileen Lee in 2013.

2) Ministry of SMEs and Startups, April 9, 2020, Rising to world’s venture capital powerhouse: K-Unicorn Project, Press Release.

3) Among 464 unicorns, only ten firms are from Korea.

4) For example, refer to “The unicorn bubble is bursting” (Forbes, October 7, 2019).

Gornall and Strebulaev (2020) showed that the reported valuation of unicorns is 48% higher than the fair value on average (Gornall, W. Strebulaev, I. A., 2020, Squaring venture capital valuations with reality, Journal of Financial Economics 135, 120-143).

5) Shares such as convertible preferred shares are senior to common shares. This limits or sometimes completely eliminates the founder’s share of profits if the firm value turns below a certain level at the time of investment exit via IPO or M&A.

6) According to Gornall and Strebulaev (2020), a unicorn on average issues eight classes of shares.

7) Preqin, Global venture capital perspectives: A Preqin & Vertex Study.

8) Economist, April 4, 2020, Exit unicorns, pursued by bears.

9) It’s possible for private market investors to invest in startups because they expect IPO to help transfer their risk to public market investors (Forbes, October 7, 2019).

10) For example, WeWork is regarded as an investment failure for SoftBank Vision Fund.

11) When Luckin Coffee got mired in an accounting fraud and declared default, its shares dipped from $26.2 on April 1, 2020 to $6.4 the next day.

12) “Blitzscaling” was coined to refer to such a strategy.