Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

A Thought on Factors behind Korea’s Recently Rising Household Savings Rate

Publication date Nov. 24, 2020

Summary

Korea’s recent rise in the household savings rate could have stemmed from its slowed growth trend and rising uncertainties in the post-crisis era. The Covid-19 pandemic is expected to deepen Korea’s post-crisis slump in productivity and dynamics, which could further drag down Korea’s growth trend. Rising uncertainties due to the recent pandemic is further deepening concerns about Korea’s sluggish economic growth. All those circumstances reinforce the need to exert long-term effort to address Korea’s high uncertainties and dampened growth trend both of which are reflected in the recent rise in Korea’s household savings rate. A boost in income via a resumed growth trend could not only give households room for saving, but also improve Korea’s rate of increase in consumption that has long been below its economic growth. Also notable is that the households particularly vulnerable to Covid-19 shocks tend to have a high percentage of consumption in their income. This requires a dual approach: A short-term fix is to ease their income uncertainties for better consumer sentiment. In a long run, it is desirable to encourage savings and investment activities for their post-retirement income.

In the face of the novel coronavirus disease-19 (Covid-19) in the first half of 2020, households across the globe have been cut their spending while increasing their savings, which pushed up overall household savings rates. Such an increase could be attributable to many reasons: Some argue economic shutdowns (e.g., halts in manufacturing facilities, restricted movement, shop closures, etc.) slowed consumption and instead increased involuntary savings, while others say households’ precautionary savings rose in preparation for uncertain economic conditions.1) Both in common are reflecting dampened consumption at the wake of rising uncertainties and economic lockdowns triggered by Covid-19, rather than an increase in household income leading to more room for savings. The higher savings rate could be also explained by slowed economic growth due to Covid-19 and the resultant weakening of expectations for higher household income, which slowed down the increase in household consumption.2) This means that the economy’s growth trend combined with economic lockdowns and rising uncertainties is a factor equally important to raising household savings rates during the pandemic era.

According to the permanent income hypothesis, a slowed growth trend undermines household expectations for higher future income, thus dragging down consumption increases and pushing up household savings rates. As Covid-19 is expected to slow down Korea’s long-term economic growth trend (Kang, 2020), Korea’s household savings rate is expected to remain higher than that of the past. In particular, if the slowed growth trend lingers even after economic lockdowns and economic uncertainties from Covid-19 are eased and economic activities resume, this could exert upward pressure on household savings rates. Against the backdrop, this article first explores Korea’s household savings rate trend, and the importance of rising uncertainties and slowed growth as a factor increasing household savings rates.

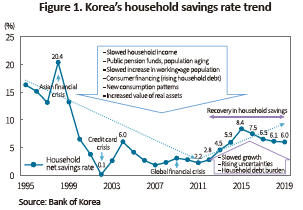

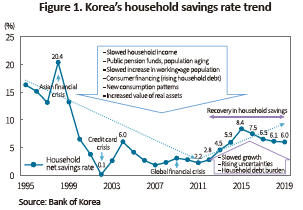

Korea’s household savings trend

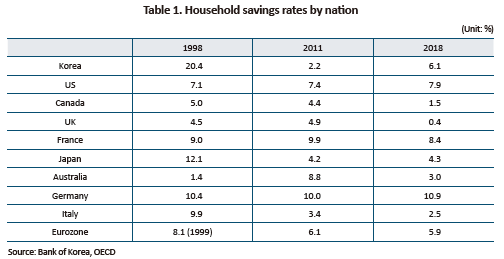

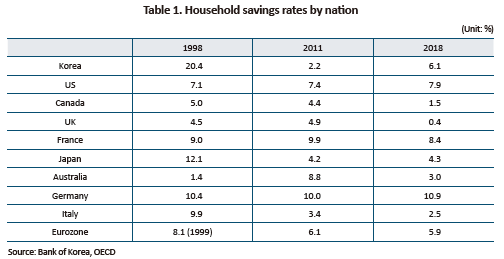

Figure 1 illustrates Korea’s long-term household savings rate from 1995 to 2019.3) Korea had achieved high growth and kept its household savings rate quite high before the Asian financial crisis, At the wake of the crisis, however, the household savings rate plummeted drastically. As shown in Figure 1, it’s hard to find any OECD nation whose household savings rate dropped as abruptly as in Korea during the Asian financial crisis. It was only after 2011 when Korea’s household savings rate began picking up again from 2.2% in 2011 finally to 8.4% in 2015. Although slightly decreasing ever since, Korea’s household savings rate is still at a high level, compared with that during few years right after the Asian financial crisis. Notably, Korea’s household savings rate resumed to the pre-crisis level, and is currently similar to or not lower than the OECD level. Table 1 shows that the average household savings rate in the eurozone stood at 5.9% as of 2018, marking a similar level to Korea’s. As of 2011, Korea was one of the nations showing a low household savings rate with Japan, Australia, and Italy. However, Korea topped those nations as of 2018, with its household savings rate at 6.8% compared to Japan’s 4.3%, Australia’s 3.0%, and Italy’s 2.5%. As a factor changing household savings rates, existing literature (Shin & Lee, 2010; Kim, Sung & Park, 2018) present household income, demographic shifts, taxes and other social contributions, real interest rates, household financing conditions, home prices, changes in essential spending, etc. However, those factors are limited in fully explaining why household savings rates have risen recently because they are mostly pointed to as a factor dragging down household savings rate.

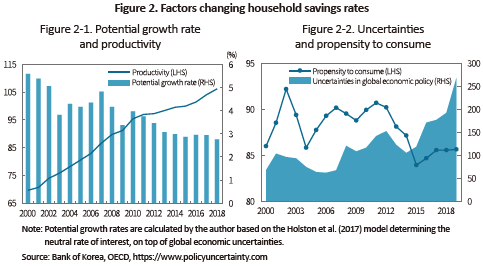

Factors behind the post-crisis increase in household savings rates: Consumption slump due to slowed growth and rising uncertainties

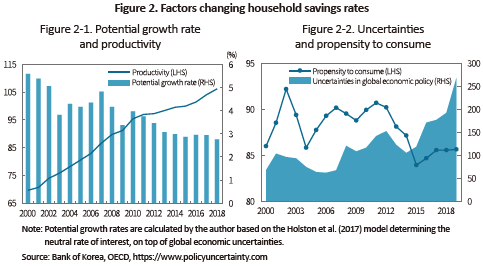

The recent rise in household savings rates could stem from an economic slowdown that has lingered since the global financial crisis. Korea, too, has seen a slowdown in its growth trend.4) It’s possible for a slowed growth trend to have cast a shadow over economic entities’ long-term growth outlook, which could have contracted household consumption and pushed up the savings rate (Aguiar & Gopinath, 2007). Another possibility is that growing uncertainties might have predisposed households to increase their precautionary savings and lower their propensity to consume, which could lead to a higher household savings rate.5) Figure 2-1 demonstrates potential growth and multi-factor productivity (OECD), a gauge of Korea’s economic fundamentals, whereas Figure 2-2 represents global uncertainties and Korea’s propensity to consume (the percentage of consumption expenditure in disposable income) which is computed based on Korea’s National Accounts. It appears that the growth trend of productivity has slowed since 2010, which could have impacted slowed potential growth in Korea’s economy. Dampened potential growth (slowed growth trend) could possibly have weakened household expectations for future income increases, imposing an impact on contracting consumption increases and pushing up the savings rate. Also estimated is the impact of global uncertainty factors: They could have pushed up Korea’s economic uncertainties and dragged down households’ propensity to consume, which seems to have played some part in increasing the household savings rate. In short, the rising household savings rate appears to be related to Korea’s consumption slump arising from the sluggish growth trend and rising uncertainties.

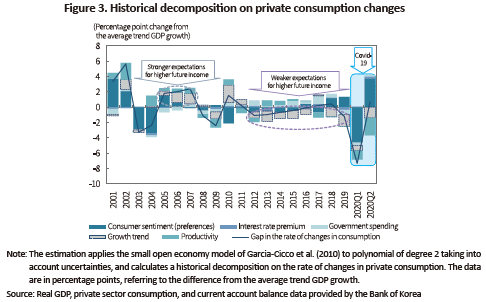

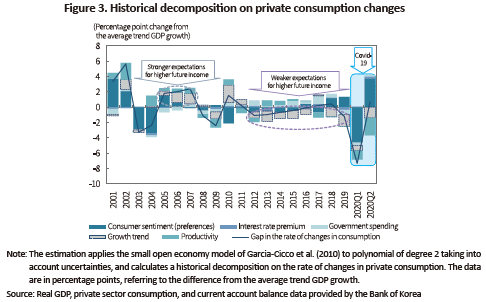

Figure 3 provides a structural decomposition on macroeconomic factors behind changes in Korea’s private sector consumption. It is confirmed that changes in private sector consumption is primarily swayed by shocks to consumer sentiment (consumer preferences) and growth trends. Changes in consumer preferences, in particular, are found to have increased volatility in the rate of change in private sector consumption. Notably, the rising growth trend right before the global financial crisis appears to have fueled household expectations for higher future income, increasing then sluggish consumption after being hit by the credit card crisis. On the other hand, Korea’s growth in private sector consumption has slowed down for more than a decade to fall below the trend GDP growth since the global financial crisis with a slowdown in Korea’s growth trend. This implies that the increase in the household savings rate after 2011 could have resulted from the slowed growth trend and weakened expectations for higher household income.

Covid-19 and the future of Korea’s household savings rate

As Covid-19 first identified in China to spread to the globe, nations one after another implemented a series of economic lockdowns from halting manufacturing facilities to restricting movements and operations, which has sent the global economy into unprecedented recession. In Figure 3, the primary cause behind the abrupt decline in private sector consumption triggered by Covid-19 in the first quarter of 2020 is a contraction in consumer preferences, followed by productivity and the lower growth trend in order of effect size. Rising internal and external uncertainties and lockdowns due to Covid-19 could have immensely impacted businesses and households’ consumer preferences, which drastically contracted consumption. Kang (2020) expects Covid-19 to further deepen Korea’s slowed productivity and the lack of dynamics both of which have been lingering since the global financial crisis. This could further bring down Korea’s growth trend, which will weaken expectations for higher future income and thus continuously put the brakes on growth in household consumption while pushing up the household savings rate.

Until recently, a rise in household savings rate was normally viewed positive in Korea as the savings—if they are invested in private sector firms—could enhance growth potential of the economy. However, there are some disturbing aspects in the recent increase in household savings: It is reflecting not only weaker expectations for higher future household income amid Korea’s slowed growth trend, but also household jitters following uncertainties surrounding Korea’s economy, for example, the European fiscal crisis, the US-China trade dispute, and not to mention Covid-19. Simply put, the slumped growth trend and rising uncertainties could have contracted household consumption, and in the end increased the percentage of savings in household income. Those circumstances would likely lead to two possibilities: First, household savings could be concentrated in safe assets such as government bonds and cash; and second, they are unlikely to flow to private sector investment.

The findings mentioned above necessitate a renewed look at household savings rates. What Korea needs now is to exert further effort to address its rising economic uncertainties and slowed growth trend, instead of being overly positive about the recent hike in its household savings rate. If Korea could revive its economic growth and thus boost household income, this will surely give households sufficient room for savings and give a boost to consumption growth which has been long below the economic growth rate. Also notable is that the households particularly vulnerable to Covid-19 shocks tend to have a high percentage of consumption in their income. This requires a dual approach: A short-term fix is to ease their income uncertainties for better consumer preferences. In a long run, it is desirable to encourage savings and investment activities for their post-retirement income.

1) ECB President Christine Lagarde pointed to concerns that an increase in precautionary savings could slow the pace of economic recovery. By contrast, Bank of England Chief Economist Andy Haldane argued that involuntary savings due to lockdowns could dwarf precautionary savings for economic uncertainties.

2) It’s important to distinguish slowed consumption due to slowed growth from that caused by rising uncertainties. Slumped growth reflects a slowed increase in future household income, whereas rising uncertainties mean increased income uncertainties without any change in expectations for future household income.

3) In general, a household savings rate refers to a net household savings rate in Korea’s National Accounts. A household net savings rate is a ratio of household net savings to household disposable income which is the sum of individual net disposable income and changes in household net equity in pension funds.

4) A growth trend here refers to equilibrium GDP (potential GDP) that imposes no inflationary pressure and is achieved in the long run.

5) Although not discussed in detail in this article, increased burden to pay back household debt could also discourage consumer preferences and thus play some part in increasing the household savings rate.

References

Aguiar, M., Gopinath, G., 2007, Emerging market business cycles: The cycle is the trend., Journal of Political Economy 115(1), 69-102.

Garcia-Cicco, J., Pancrazi, R., Uribe, M., 2010, Real business cycles in emerging countries?, American Economic Review 100(5), 2510-31.

Holston, K., Laubach, T., Williams, J.C., 2017, Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants, Journal of International Economics 108, 59-75.

(Korean)

Kang, H.J., 2020, Long-term trend in Korea’s economy and Covid-19, KCMI Issue Paper 20-21.

Kim, H.S., Park, B.K., Sung, H.K, 2018, Recent rise in household savings rate: Causes and implications, Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin, 72(3).

Shin, W.S., Lee, W.K., 2010, Falling household savings rate and policy challenges, Bank of Korea, BOK Economic Brief 2010-1.

According to the permanent income hypothesis, a slowed growth trend undermines household expectations for higher future income, thus dragging down consumption increases and pushing up household savings rates. As Covid-19 is expected to slow down Korea’s long-term economic growth trend (Kang, 2020), Korea’s household savings rate is expected to remain higher than that of the past. In particular, if the slowed growth trend lingers even after economic lockdowns and economic uncertainties from Covid-19 are eased and economic activities resume, this could exert upward pressure on household savings rates. Against the backdrop, this article first explores Korea’s household savings rate trend, and the importance of rising uncertainties and slowed growth as a factor increasing household savings rates.

Korea’s household savings trend

Figure 1 illustrates Korea’s long-term household savings rate from 1995 to 2019.3) Korea had achieved high growth and kept its household savings rate quite high before the Asian financial crisis, At the wake of the crisis, however, the household savings rate plummeted drastically. As shown in Figure 1, it’s hard to find any OECD nation whose household savings rate dropped as abruptly as in Korea during the Asian financial crisis. It was only after 2011 when Korea’s household savings rate began picking up again from 2.2% in 2011 finally to 8.4% in 2015. Although slightly decreasing ever since, Korea’s household savings rate is still at a high level, compared with that during few years right after the Asian financial crisis. Notably, Korea’s household savings rate resumed to the pre-crisis level, and is currently similar to or not lower than the OECD level. Table 1 shows that the average household savings rate in the eurozone stood at 5.9% as of 2018, marking a similar level to Korea’s. As of 2011, Korea was one of the nations showing a low household savings rate with Japan, Australia, and Italy. However, Korea topped those nations as of 2018, with its household savings rate at 6.8% compared to Japan’s 4.3%, Australia’s 3.0%, and Italy’s 2.5%. As a factor changing household savings rates, existing literature (Shin & Lee, 2010; Kim, Sung & Park, 2018) present household income, demographic shifts, taxes and other social contributions, real interest rates, household financing conditions, home prices, changes in essential spending, etc. However, those factors are limited in fully explaining why household savings rates have risen recently because they are mostly pointed to as a factor dragging down household savings rate.

The recent rise in household savings rates could stem from an economic slowdown that has lingered since the global financial crisis. Korea, too, has seen a slowdown in its growth trend.4) It’s possible for a slowed growth trend to have cast a shadow over economic entities’ long-term growth outlook, which could have contracted household consumption and pushed up the savings rate (Aguiar & Gopinath, 2007). Another possibility is that growing uncertainties might have predisposed households to increase their precautionary savings and lower their propensity to consume, which could lead to a higher household savings rate.5) Figure 2-1 demonstrates potential growth and multi-factor productivity (OECD), a gauge of Korea’s economic fundamentals, whereas Figure 2-2 represents global uncertainties and Korea’s propensity to consume (the percentage of consumption expenditure in disposable income) which is computed based on Korea’s National Accounts. It appears that the growth trend of productivity has slowed since 2010, which could have impacted slowed potential growth in Korea’s economy. Dampened potential growth (slowed growth trend) could possibly have weakened household expectations for future income increases, imposing an impact on contracting consumption increases and pushing up the savings rate. Also estimated is the impact of global uncertainty factors: They could have pushed up Korea’s economic uncertainties and dragged down households’ propensity to consume, which seems to have played some part in increasing the household savings rate. In short, the rising household savings rate appears to be related to Korea’s consumption slump arising from the sluggish growth trend and rising uncertainties.

As Covid-19 first identified in China to spread to the globe, nations one after another implemented a series of economic lockdowns from halting manufacturing facilities to restricting movements and operations, which has sent the global economy into unprecedented recession. In Figure 3, the primary cause behind the abrupt decline in private sector consumption triggered by Covid-19 in the first quarter of 2020 is a contraction in consumer preferences, followed by productivity and the lower growth trend in order of effect size. Rising internal and external uncertainties and lockdowns due to Covid-19 could have immensely impacted businesses and households’ consumer preferences, which drastically contracted consumption. Kang (2020) expects Covid-19 to further deepen Korea’s slowed productivity and the lack of dynamics both of which have been lingering since the global financial crisis. This could further bring down Korea’s growth trend, which will weaken expectations for higher future income and thus continuously put the brakes on growth in household consumption while pushing up the household savings rate.

Until recently, a rise in household savings rate was normally viewed positive in Korea as the savings—if they are invested in private sector firms—could enhance growth potential of the economy. However, there are some disturbing aspects in the recent increase in household savings: It is reflecting not only weaker expectations for higher future household income amid Korea’s slowed growth trend, but also household jitters following uncertainties surrounding Korea’s economy, for example, the European fiscal crisis, the US-China trade dispute, and not to mention Covid-19. Simply put, the slumped growth trend and rising uncertainties could have contracted household consumption, and in the end increased the percentage of savings in household income. Those circumstances would likely lead to two possibilities: First, household savings could be concentrated in safe assets such as government bonds and cash; and second, they are unlikely to flow to private sector investment.

The findings mentioned above necessitate a renewed look at household savings rates. What Korea needs now is to exert further effort to address its rising economic uncertainties and slowed growth trend, instead of being overly positive about the recent hike in its household savings rate. If Korea could revive its economic growth and thus boost household income, this will surely give households sufficient room for savings and give a boost to consumption growth which has been long below the economic growth rate. Also notable is that the households particularly vulnerable to Covid-19 shocks tend to have a high percentage of consumption in their income. This requires a dual approach: A short-term fix is to ease their income uncertainties for better consumer preferences. In a long run, it is desirable to encourage savings and investment activities for their post-retirement income.

1) ECB President Christine Lagarde pointed to concerns that an increase in precautionary savings could slow the pace of economic recovery. By contrast, Bank of England Chief Economist Andy Haldane argued that involuntary savings due to lockdowns could dwarf precautionary savings for economic uncertainties.

2) It’s important to distinguish slowed consumption due to slowed growth from that caused by rising uncertainties. Slumped growth reflects a slowed increase in future household income, whereas rising uncertainties mean increased income uncertainties without any change in expectations for future household income.

3) In general, a household savings rate refers to a net household savings rate in Korea’s National Accounts. A household net savings rate is a ratio of household net savings to household disposable income which is the sum of individual net disposable income and changes in household net equity in pension funds.

4) A growth trend here refers to equilibrium GDP (potential GDP) that imposes no inflationary pressure and is achieved in the long run.

5) Although not discussed in detail in this article, increased burden to pay back household debt could also discourage consumer preferences and thus play some part in increasing the household savings rate.

References

Aguiar, M., Gopinath, G., 2007, Emerging market business cycles: The cycle is the trend., Journal of Political Economy 115(1), 69-102.

Garcia-Cicco, J., Pancrazi, R., Uribe, M., 2010, Real business cycles in emerging countries?, American Economic Review 100(5), 2510-31.

Holston, K., Laubach, T., Williams, J.C., 2017, Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants, Journal of International Economics 108, 59-75.

(Korean)

Kang, H.J., 2020, Long-term trend in Korea’s economy and Covid-19, KCMI Issue Paper 20-21.

Kim, H.S., Park, B.K., Sung, H.K, 2018, Recent rise in household savings rate: Causes and implications, Bank of Korea, Monthly Bulletin, 72(3).

Shin, W.S., Lee, W.K., 2010, Falling household savings rate and policy challenges, Bank of Korea, BOK Economic Brief 2010-1.