Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Public vs. Private Corporation, Public vs. Private Market

Publication date Apr. 07, 2021

Summary

In the US, the number of public corporations (listed firms) is on the steady decline after reaching the peak in 1996. Some often-mentioned causes for the reluctance of founders and managers to go public include concerns about the loss of control over key decision making, short-termism of public market investors, and the costs listed firms bear to remain listed. However, a more fundamental cause is said to lie in the US public market’s failure to catch up with latest changes in new firm characteristics and business models for transforming itself into a marketplace more fitted for innovative start-ups. Another factor in play is the well-developed private market in the US via which start-ups can raise capital and early-stage investors can exit their investment without tapping into the public market.

Surely, a well-functioning and active private market in terms of firms’ financing, early-stage investors’ exit, and corporate governance could broaden managers’ choices of whether to go public or not. However, from the perspective of investors—especially retail ones with limited access to the private market, the fall in the number of listed firms could have an adverse impact of reducing a set of investment opportunities. It would be a key policy challenge to strike an optimal balance between private and public markets, which should be preconditioned by objective research for accumulating sufficient knowledge and evidence.

Surely, a well-functioning and active private market in terms of firms’ financing, early-stage investors’ exit, and corporate governance could broaden managers’ choices of whether to go public or not. However, from the perspective of investors—especially retail ones with limited access to the private market, the fall in the number of listed firms could have an adverse impact of reducing a set of investment opportunities. It would be a key policy challenge to strike an optimal balance between private and public markets, which should be preconditioned by objective research for accumulating sufficient knowledge and evidence.

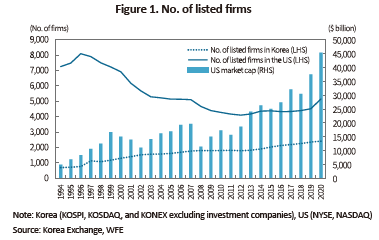

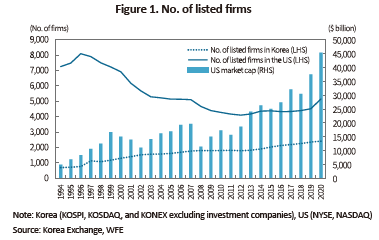

US Financial Economist Michael Jenson (1989) famously predicted “the eclipse of the public corporation” as the public corporation was no longer an effective form of corporation in the US economy. According to his prediction, the private corporation—highly-leveraged and owned by a small number of large-scale, professional investors—would rise to the mainstream. Jenson (1989) argued the eclipse would be caused by the inefficiency arising as a result of conflicts of interest between shareholders and the management, and the agency costs of free cash flows. Although such a dramatic demise has yet to come for three decades since his study was published, the number of US listed firms1) is on the steady decline after reaching the peak in 1996 as illustrated in Figure 1.2) The declining number of listed firms implies that the number of delisted firms dwarfs the number of newly listed firms,3) which according to Figure 1 has been a persistent trend for a considerable period of time.

Traditionally, going public to be listed on a public market has been perceived as an essential process during which a firm raises funds for long-term growth and early-stage investors exit their investment by selling their stake. This fueled the widespread belief that a well-established and efficiently-functioning public market is a crucial part of the development of the national economy. That being said, the decline in the number of listed firms observed in the US has significance, possibly implying a crucial problem or a meaningful change taking place especially in the public market and the real economy (the corporate sector). Against the backdrop, this article tries to overview the precedent literature on the causes to the phenomenon, and to come up with the challenges and implications associated with the roles of the public and private markets and the relationship between them.

Causes behind the fall in the number of listed firms in the US

In the US, the loss of control over key management decisions appears to be mentioned most frequently as the cause to the reluctance of founders and managers to go public. They believe that the process of going public via IPO would only lower their stake, and that the larger say of outside shareholders would make it more difficult for them to maintain their corporate vision and strategies established since the foundation of their firm. Although no corporation is free from shareholder controls and oversight, from a founder’s perspective public market investors who will gain more control in a public firm are more likely to prioritize short-term financial results over long-term vision and growth without in-depth understanding about the business model and the founder’s vision shared by a small number of professional, early-stage investors, which would give rise to conflicts of interest issues.4) It is the context that well explains the motives behind introducing corporate governance tools such as multiple voting rights. However, Bebchuk (2021) argues that there is no empirical evidence about the short-termism of public market investors, and that the issue of short-termism could be addressed by designing a proper management remuneration scheme, not by introducing a defensive tactic.

Another cause often mentioned behind the reluctance to go public is the cost of being listed, including regulatory costs for disclosure, accounting, investor protection, corporate governance, etc. However, this meets several counterarguments: The decline in the number of public corporations is hardly caused by regulatory costs as it began well before public corporations were subject to tighter regulation such as the Regulation Fair Disclosure and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Doidge et al., 2017); Also, the cost of going public did not actually fall after the JOBS Act that was initially intended to promote more new growth firms to go public (Chaplinsky et al., 2017).

Others such as Kahle & Stulz (2017), Doidge et al. (2018), and Stulz (2020) argue that the decreased number of IPOs in the US stems from more fundamental changes that have been taking place in the US economy for the past three decades, especially, the growing importance of intangible assets among the newly emerging firms driving growth of the US economy. Although more and more firms are focusing more on intangible assets, the change and the resultant business model are neither fully understood by public market investors nor timely reflected in accounting and listing standards, which led the public market to center on large corporations and to become unfit for meeting the financing demand of innovative start-ups oriented by intangible assets. With regard to that, Doidge et al. (2018) point out that what is implied by the fall in the number of public corporations in the US is the lower efficacy of the public market, not public corporations. Figure 1 demonstrates a steady decline in the number of listed firms with a persistent increase in their market cap, suggesting an increase in firm size of listed firms and a deepening level of market concentration.

Another factor in play for lowering the need for going public is the well-developed private market in the US that could sufficiently meet the financing demand of startups on behalf of the public market. Without having to deal with an unspecified number of public market investors, it is much easier now than before for start-ups to raise capital from a small number of private market investors such as venture capital and private equity funds who have both expertise and knowledge about their business model (Stulz, 2020).

Compared to a public market, private market liquidity is quite low. As mentioned before, going public is crucial as it provides early-stage investors an investment exit channel.5) The US private market provides liquidity to private corporation shares via flexible transaction structures such as active M&A, secondaries where pre-existing investor commitments change hands, and fund recapitalization secondaries, etc.,6) which helps early-stage investors to depend less on IPOs for investment exits.7) Hence, the fall in the number of IPOs by VC-backed firms could lie in the choice of more founders and venture capital to remain unlisted than before (Ewens & Farre-Mensa, 2017).

Implications and challenges

As illustrated in Figure 1, Korea sees the number of listed firms rising stably, unlike what has been observed in the US. However, the arguments presented about the causes behind the decreased number of listed firms have ample implications about the relationship between the public and private markets in Korea.

Among others, the corporate sector in Korea has observed firm characteristics changing with the rising importance of intangible assets and the emergence of new business models in the 2000s. Accordingly, the public market8) has strived for encouraging more innovative start-ups to be listed on the public market by adjusting market entry criteria and introducing new listing standards and the special listing standards. Such effort, however, largely focuses on lowering the market entry barrier, which is raising concerns about the potential adverse impact on investor protection and public market integrity. As illustrated in the US case, an active private market helps broaden choices by enabling firms and early-stage investors to raise growth capital and exit their investments without going public. At the same time, by leaving the firms unable to meet the entry barrier in the area of the private market, the public market could help prevent the deregulation from becoming excessive enough to undermine market integrity.

A well-functioning private market is also positive for corporate governance as it helps founders and managers to choose either to become a public corporation disciplined by public regulation and an unspecified number of investors, or to remain as a private corporation governed by a small number of professional private market investors. Such an environment would dilute the significance of debates on whether to grant multiple voting rights to the founder’s shares for a stronger incentive for going public, or whether to protect the interest of trader-like investors in corporate governance consideration.

However, the issue between the public and private markets requires a broader perspective going beyond the corporate sector. A decreased number of listed firms means a smaller set of investment opportunities open for the majority of retail investors. The path via which retail investors can participate in a private market is quite limited, which could raise concerns that a shrinking public market and an expanding private market would only make a small number of professional investors the dominance force of the capital markets. In particular, the on-going Covid-19 outbreak is highlighting the importance of retail investors both in Korea and the US, making the public market even more important for investors.

The discussions in this article suggest that the roles and positions of public and private markets could change significantly in the capital markets going forward, and that one of the important policy challenges ahead is to strike a balance between the positions of the two markets. Towards that end, there should be sufficient and objective research effort to accumulate knowledge and evidence, which poses an important task for the relevant academia.

1) In this article, the terms “public corporation” and “listed firm” are used interchangeably.

2) Although the pace is slower than the US, the decline in the number of listed firms is also observed in the UK and Germany.

3) In the US stock market, M&A accounts for the largest proportion in the causes of delisting (Kim & Kwon, 2017; Doidge et al., 2017).

4) This line of views held by start-up founders is well summarized in Ries (2011), the founder of Long-Term Stock Exchange (LTSE).

5) Martin (2014) argues this is one of the reasons that the prediction of Jensen (1989) did not materialize before the mid-1990s.

6) For more details on fund recapitalization secondaries, refer to Park (2021).

7) Of the channels of investment exits by venture capital, selling and redeeming equity and IPOs account for more than 60% in Korea, while M&A represents an overwhelmingly large proportion of 89% in the US (Kim, 2017).

8) Korea’s public market is the Korea Exchange (KOSPI, KOSDAQ, and KONEX).

References

Bebchuk, L.A., 2021, Don’t let the short-termism bogeyman scare you, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb.

Chaplinsky, S., Hanley, K.W., Moon, S.K., 2017, The JOBS Act and the costs of going public, Journal of Accounting Research 55, 795-836.

Doidge, C., Karolyi, G.A., Stulz, R.M., 2017, The US listing gap, Journal of Financial Economics 123, 464-487.

Doidge, C., Kahle, K.M., Karolyi, G.A., Stulz, R.M., 2018, Eclipse of the public corporation or eclipse of the public markets?, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 30, 8-16.

Ewens, M., Farre-Mensa, J., 2017, The evolution of the private equity market and the decline in IPOs, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.

Jensen, M.C., 1989, Eclipse of the public corporation, Harvard Business Review Sep-Oct.

Kahle, K.M., Stulz, R.M., 2017, Is the US public corporation in trouble?, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, 67-88.

Martin, R.L., 2014, The public cororation is finally in eclipse, Harvard Business Review Mar-Apr.

Ries, E., 2011, The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful business, Crown Publishing.

Stulz, R.M., 2020, Public versus private equity, Oxford Economic Policy Review 36, 275-290.

(Korean)

Kim, J.S., Kwon, M.K., 2017, Risk-return relationship in Korea’s capital markets, Proceedings of the Roles of Capital Markets for Another Next Leap Forward Conference, Korea Capital Market Institute.

Kim, J.S., 2017, Entrepreneurial capital exit market: Current state and challenges, Proceedings of the Role of Finance for Innovative Growth Seminar, Korea Capital Market Institute.

Park, Y.R., 2021, Roles of fund recapitalization secondaries in developing Korea’s risk capital market, KCMI Opinion 2021-01, Korea Capital Market Institute.

Causes behind the fall in the number of listed firms in the US

In the US, the loss of control over key management decisions appears to be mentioned most frequently as the cause to the reluctance of founders and managers to go public. They believe that the process of going public via IPO would only lower their stake, and that the larger say of outside shareholders would make it more difficult for them to maintain their corporate vision and strategies established since the foundation of their firm. Although no corporation is free from shareholder controls and oversight, from a founder’s perspective public market investors who will gain more control in a public firm are more likely to prioritize short-term financial results over long-term vision and growth without in-depth understanding about the business model and the founder’s vision shared by a small number of professional, early-stage investors, which would give rise to conflicts of interest issues.4) It is the context that well explains the motives behind introducing corporate governance tools such as multiple voting rights. However, Bebchuk (2021) argues that there is no empirical evidence about the short-termism of public market investors, and that the issue of short-termism could be addressed by designing a proper management remuneration scheme, not by introducing a defensive tactic.

Another cause often mentioned behind the reluctance to go public is the cost of being listed, including regulatory costs for disclosure, accounting, investor protection, corporate governance, etc. However, this meets several counterarguments: The decline in the number of public corporations is hardly caused by regulatory costs as it began well before public corporations were subject to tighter regulation such as the Regulation Fair Disclosure and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Doidge et al., 2017); Also, the cost of going public did not actually fall after the JOBS Act that was initially intended to promote more new growth firms to go public (Chaplinsky et al., 2017).

Others such as Kahle & Stulz (2017), Doidge et al. (2018), and Stulz (2020) argue that the decreased number of IPOs in the US stems from more fundamental changes that have been taking place in the US economy for the past three decades, especially, the growing importance of intangible assets among the newly emerging firms driving growth of the US economy. Although more and more firms are focusing more on intangible assets, the change and the resultant business model are neither fully understood by public market investors nor timely reflected in accounting and listing standards, which led the public market to center on large corporations and to become unfit for meeting the financing demand of innovative start-ups oriented by intangible assets. With regard to that, Doidge et al. (2018) point out that what is implied by the fall in the number of public corporations in the US is the lower efficacy of the public market, not public corporations. Figure 1 demonstrates a steady decline in the number of listed firms with a persistent increase in their market cap, suggesting an increase in firm size of listed firms and a deepening level of market concentration.

Another factor in play for lowering the need for going public is the well-developed private market in the US that could sufficiently meet the financing demand of startups on behalf of the public market. Without having to deal with an unspecified number of public market investors, it is much easier now than before for start-ups to raise capital from a small number of private market investors such as venture capital and private equity funds who have both expertise and knowledge about their business model (Stulz, 2020).

Compared to a public market, private market liquidity is quite low. As mentioned before, going public is crucial as it provides early-stage investors an investment exit channel.5) The US private market provides liquidity to private corporation shares via flexible transaction structures such as active M&A, secondaries where pre-existing investor commitments change hands, and fund recapitalization secondaries, etc.,6) which helps early-stage investors to depend less on IPOs for investment exits.7) Hence, the fall in the number of IPOs by VC-backed firms could lie in the choice of more founders and venture capital to remain unlisted than before (Ewens & Farre-Mensa, 2017).

Implications and challenges

As illustrated in Figure 1, Korea sees the number of listed firms rising stably, unlike what has been observed in the US. However, the arguments presented about the causes behind the decreased number of listed firms have ample implications about the relationship between the public and private markets in Korea.

Among others, the corporate sector in Korea has observed firm characteristics changing with the rising importance of intangible assets and the emergence of new business models in the 2000s. Accordingly, the public market8) has strived for encouraging more innovative start-ups to be listed on the public market by adjusting market entry criteria and introducing new listing standards and the special listing standards. Such effort, however, largely focuses on lowering the market entry barrier, which is raising concerns about the potential adverse impact on investor protection and public market integrity. As illustrated in the US case, an active private market helps broaden choices by enabling firms and early-stage investors to raise growth capital and exit their investments without going public. At the same time, by leaving the firms unable to meet the entry barrier in the area of the private market, the public market could help prevent the deregulation from becoming excessive enough to undermine market integrity.

A well-functioning private market is also positive for corporate governance as it helps founders and managers to choose either to become a public corporation disciplined by public regulation and an unspecified number of investors, or to remain as a private corporation governed by a small number of professional private market investors. Such an environment would dilute the significance of debates on whether to grant multiple voting rights to the founder’s shares for a stronger incentive for going public, or whether to protect the interest of trader-like investors in corporate governance consideration.

However, the issue between the public and private markets requires a broader perspective going beyond the corporate sector. A decreased number of listed firms means a smaller set of investment opportunities open for the majority of retail investors. The path via which retail investors can participate in a private market is quite limited, which could raise concerns that a shrinking public market and an expanding private market would only make a small number of professional investors the dominance force of the capital markets. In particular, the on-going Covid-19 outbreak is highlighting the importance of retail investors both in Korea and the US, making the public market even more important for investors.

The discussions in this article suggest that the roles and positions of public and private markets could change significantly in the capital markets going forward, and that one of the important policy challenges ahead is to strike a balance between the positions of the two markets. Towards that end, there should be sufficient and objective research effort to accumulate knowledge and evidence, which poses an important task for the relevant academia.

1) In this article, the terms “public corporation” and “listed firm” are used interchangeably.

2) Although the pace is slower than the US, the decline in the number of listed firms is also observed in the UK and Germany.

3) In the US stock market, M&A accounts for the largest proportion in the causes of delisting (Kim & Kwon, 2017; Doidge et al., 2017).

4) This line of views held by start-up founders is well summarized in Ries (2011), the founder of Long-Term Stock Exchange (LTSE).

5) Martin (2014) argues this is one of the reasons that the prediction of Jensen (1989) did not materialize before the mid-1990s.

6) For more details on fund recapitalization secondaries, refer to Park (2021).

7) Of the channels of investment exits by venture capital, selling and redeeming equity and IPOs account for more than 60% in Korea, while M&A represents an overwhelmingly large proportion of 89% in the US (Kim, 2017).

8) Korea’s public market is the Korea Exchange (KOSPI, KOSDAQ, and KONEX).

References

Bebchuk, L.A., 2021, Don’t let the short-termism bogeyman scare you, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb.

Chaplinsky, S., Hanley, K.W., Moon, S.K., 2017, The JOBS Act and the costs of going public, Journal of Accounting Research 55, 795-836.

Doidge, C., Karolyi, G.A., Stulz, R.M., 2017, The US listing gap, Journal of Financial Economics 123, 464-487.

Doidge, C., Kahle, K.M., Karolyi, G.A., Stulz, R.M., 2018, Eclipse of the public corporation or eclipse of the public markets?, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 30, 8-16.

Ewens, M., Farre-Mensa, J., 2017, The evolution of the private equity market and the decline in IPOs, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.

Jensen, M.C., 1989, Eclipse of the public corporation, Harvard Business Review Sep-Oct.

Kahle, K.M., Stulz, R.M., 2017, Is the US public corporation in trouble?, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, 67-88.

Martin, R.L., 2014, The public cororation is finally in eclipse, Harvard Business Review Mar-Apr.

Ries, E., 2011, The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful business, Crown Publishing.

Stulz, R.M., 2020, Public versus private equity, Oxford Economic Policy Review 36, 275-290.

(Korean)

Kim, J.S., Kwon, M.K., 2017, Risk-return relationship in Korea’s capital markets, Proceedings of the Roles of Capital Markets for Another Next Leap Forward Conference, Korea Capital Market Institute.

Kim, J.S., 2017, Entrepreneurial capital exit market: Current state and challenges, Proceedings of the Role of Finance for Innovative Growth Seminar, Korea Capital Market Institute.

Park, Y.R., 2021, Roles of fund recapitalization secondaries in developing Korea’s risk capital market, KCMI Opinion 2021-01, Korea Capital Market Institute.