Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Current State of Virtual Assets: Issuance and Trading

Publication date Aug. 10, 2021

Summary

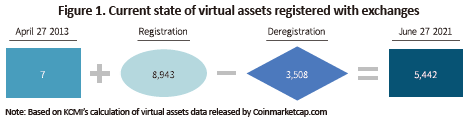

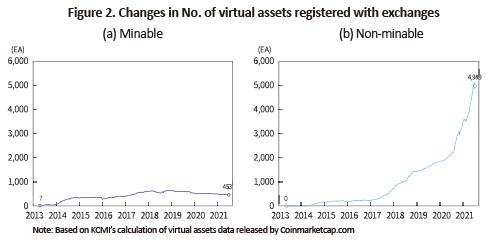

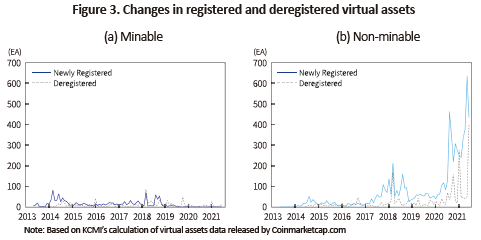

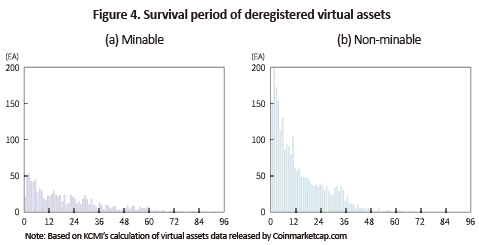

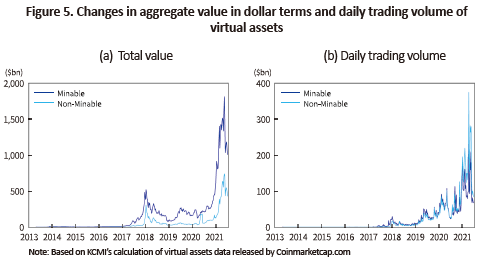

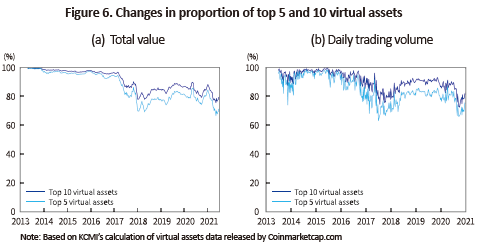

Over the past eight years and three months, a total of 8,950 virtual assets have been registered with virtual asset exchanges in the world, of which almost 40% have ended up being deregistered. Around 90.5% of all deregistered virtual assets disappeared from the market within three years, whereas quite a few got deregistered after more than five years from their registration with exchanges. In dollar terms, the aggregate value of virtual assets hits a record high of $2,534.9 billion in May 2021, with the total volume of daily trading reaching as high as $601.6 billion in April 2021. However, the aggregate value plummeted to $1,437.2 billion and the total volume of daily trading also declined to $151.6 billion as of June 27 2021. What is notable is that a small number of virtual assets account for the majority of both the aggregate value of virtual assets and daily trading volume, respectively. Meanwhile, the daily trading volume of non-minable and pre-mined virtual assets has recently surpassed that of the minable whose prices have already set at a higher level, driving price fluctuations of virtual assets.

Prices of virtual assets have spiked at an almost incomprehensible pace since the second half of 2020, fueling several controversies that had been raised in the past. Currently, fierce debates are still underway about virtual assets without any conclusion.1) At this point, it is important and necessary to understand what virtual assets exactly are before engaging in further discussions about them. Thus, this article takes a close look at the current state of virtual assets issuance and trading based on analysis of the virtual assets data compiled and released by Coinmarketcap.com every week from April 2013.

Definition and type of virtual assets

It has been agreed to use the terms such as virtual asset, cryptoasset and digital asset officially or internationally. Still, virtual currency, cryptocurrency or digital currency are widely used as terms representing virtual assets. However, there seem to be no virtual currencies, no cryptocurrencies, or no digital currencies that are counted as real money or currency. (Treasury Committee in House of Commons, 2018; Prasad, May 20 2021).

Although the functioning currencies are traditionally understood to serve as a store of value, a medium of exchange and a unit of account, even Bitcoin, the most prevailing virtual asset in the market, rarely performs all these functions. Furthermore, Bitcoin is usually perceived by the general public as an investment on which they could gain capital profits, and has been traded more actively than any other virtual assets. In line with this view, it seems more reasonable to recognize Bitcoin as a type of assets rather than a currency.

Such perception has been gaining ground since mid-2017. A case in point is that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) introduced the virtual currency concept in June 2014 in an effort to prevent virtual assets from being used for money laundering and terrorist financing, but in October 2018 decided to newly introduce the definition of a virtual asset and changed the previously used term of virtual currency into virtual asset (FATF, 2015; FATF, 2019).

In addition, the terms of virtual asset, cryptoasset and digital asset have been officially used by major economies including the US and the UK as well as international organizations such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) (Cuervo et al., 2019; FSB, 2018; HM Treasury et al., 2018; IOSCO, 2020; SEC, 2019). In Korea, a virtual asset was first defined as a legal term under the March 2020 amendment to the Act on Reporting and Using Specified Financial Transaction Information.

The definition and term representing a virtual asset vary slightly by country and international agency. The definition of a virtual asset by FATF is a ‘digital representation of value that can be digitally traded, transferred, or used for a purpose of payment or investment, excluding a digital representation of legal tender, securities and other financial assets’. On the other hand, IOSCO uses the term cryptoasset, instead of virtual asset, which falls into the definition of a form of private assets based on encryption or distributed ledger technology. The primary term employed by the UK is cryptoasset while the US refers to a virtual asset as a digital asset under the definition similar to IOSCO’s.

In accordance with Article 2 Paragraph 3 of the Korean Act on Reporting and Using Specified Financial Transaction Information, a virtual asset is defined as a digital token with economic value which can be digitally traded or transferred and all relevant rights. However, items whose disposal and use are limited by an issuer, tangible and intangible outcomes acquired via games, digital money, digital securities, and digital bills are excluded from virtual assets.

By the way, virtual assets can be classified into the categories of exchange token, utility token and security token depending on their own economic function and legal nature (HM Treasury et al., 2018).2) To put it more simply, an exchange token refers to a virtual asset issued to serve as a medium of exchange without imitations on its disposal or use, whereas a utility token means a virtual asset whose disposal is limited by an issuer and a security token represents a virtual asset that meets legal requirements of securities.

Current state of virtual asset issuance

A virtual asset was originally devised to serve as a means of payment in the peer-to-peer payment and settlement system (referred to as “P2P payment system”) underpinned by distributed ledger technology. For such use, the creator of the Bitcoin cryptocurrency known by a pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto designed Blockchain—the first and original form of distributed ledger—where a participant who first validates or conducts proof of work for authenticity of a transaction is given Bitcoin as rewards for their labor. This process was named ‘mining’ by Satoshi Nakamoto.

For Bitcoin to be mined or issued, it requires on-chain transactions in which Bitcoin is used as a means of payment in the P2P payment system. Otherwise, there would be no demand for proof of work and thus, Bitcoin mining never takes place. As such, a virtual asset issued through mining refers to a minable virtual asset.

However, not all virtual assets are issued via mining. There are other types such as non-minable and pre-mined virtual assets. For issuance, the non-minable is sold to a digital wallet holder belonging to the issuer’s distributed ledger network and then, is proven valid, while the pre-mined is pre-sold by its issuer for the purpose of raising capital from or getting sponsored by many unspecified individuals. For these reasons, the issuance of non-minable or pre-mined virtual assets are also referred to as token sales.3)

In general, an exchange token is issued via mining while the issuance of a utility token and a security token is characterized by being non-minable. However, some virtual assets known to act as exchange tokens are issued in a non-minable method. This may be due to lack of economic efficiency in the mining-based issuance, but it is largely attributable to the fact that a virtual asset cannot be issued unless it is widely used as a means of payment.

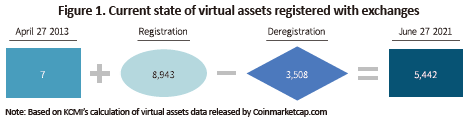

According to the analysis results of virtual asset data presented by Coinmarketcap.com, the number of virtual assets registered with exchanges around the world reached 8,950 during the period from April 27 2013 to June 27 2021. Among them, a total of 5,442 virtual assets remained registered as of June 27 2021. Given seven virtual assets already being registered and traded prior to April 27 2013, this indicates that 8,943 assets were newly registered (or issued) and 3,508 assets were deregistered or disappeared during the same period.

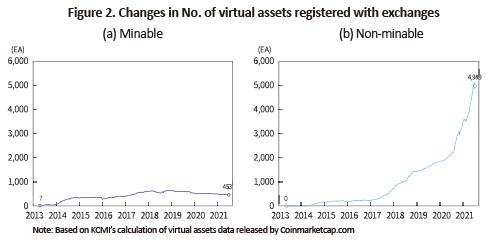

A close look at changes in virtual asset registrations categorized by issuance method reveals that much of virtual assets were primarily minable in the initial stage as shown in Figure 2. However, the non-minable has steeply increased since early 2017 up to present while the minable has shown a moderate downturn since mid-2018. As of June 27 2021, with 453 minable virtual assets being traded, the number of non-minable assets stood at 4,989, 11 times higher than that of the minable.

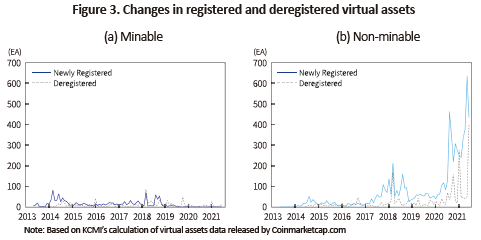

As for monthly changes in registration and deregistration, an average of 205.7 virtual assets (standard deviation of 186.7) were newly registered while 99.3 (standard deviation of 129.7) were removed from exchanges each month during the period analyzed. Depending on issuance method, fewer than five minable virtual assets were registered per month after June 2019 while the number of registered non-minable assets on a monthly basis approached 100 or higher from July 2020, hitting a record high with a total of 631 registered in May 2021. With fewer registrations, a tiny number of minable virtual assets have been deregistered from exchanges. By contrast, deregistration of the non-minable has continued an upward trend.

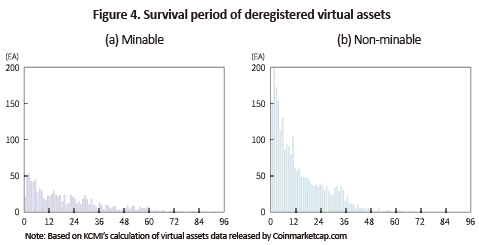

As for survival period of deregistered virtual assets, the minable was traded for an average of 21.5 months and the trading period of the non-minable was calculated as 14.1 months on average. Figure 4 illustrates that 90.5% and 52.6% of deregistered virtual assets were removed from exchanges in less than 36 months and 12 months, respectively. However, there are quite a few deregistered virtual assets whose trading period spanned 60 months (five years) or longer.

Current state of virtual asset trading

When an exchange token is traded as a medium of payment, the relevant trading data are entered in a digital wallet and the token is transferred to a third party. If its exchange value is neither in sync with the exchange value of legal tender issued by the central bank nor determined based on public consensus, the chances are slim for such a token to serve as a means of payment. This is because how an exchange token is accepted largely depends on the size of a group participating in exchange value assessment and the stability of exchange value.

An interesting fact is that most exchange tokens including Bitcoin rarely have a mechanism that determines their own exchange value. This implies that value of any exchange token can be discovered only after payment and settlement transactions via the token are repeatedly carried out without interruptions. Since the launch of the first virtual asset exchange on July 18 2010, exchange tokens have begun to trade through competitive bidding just as stocks do.4)

From then on, all forms of virtual assets have been traded and distributed under the competitive bidding system, regardless of types. For example, even a stablecoin whose mechanism makes its exchange value pegged to a certain level is being traded through competition bidding (Lyons and Viswanath-Natraj, 2020). Accordingly, the general public tend to recognize most virtual assets—irrespective of the purpose of issuance—as investments on which they can achieve capital returns.

As a result, virtual asset prices, like stock prices, have frequently changed on a daily basis, displaying much higher volatility than the stock market. This is especially evident in 2017 and 2020 when a surge in retail investors participating in virtual asset trades and their investment funds made virtual asset prices steeply rise in a short time span, thereby driving up the trading value to the extent incomparable to the previous level.

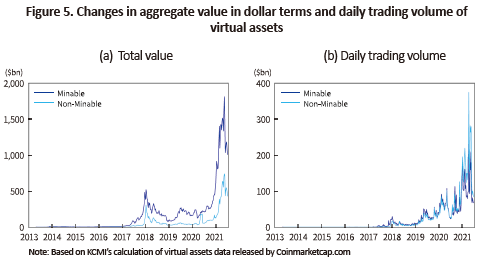

More concretely, Figure 5 shows that the total value of virtual assets in dollar terms sharply increased from early 2017 to early 2018 before showing a dramatic plunge. Since the outbreak of a global pandemic was officially declared in March 2020, the value has spiked again at an unprecedented pace, reaching a record peak of $2,543.9 billion in early May 2021 ($1,804.4 billion of the minable, $739.5 billion of the non-minable) and then plummeted until June 2021.

Meanwhile, although the number of non-minable virtual assets has rapidly risen far beyond that of minable assets since 2017, the aggregate value of minable virtual assets has always surpassed that of the non-minable in dollar terms. For instance, of the total value of virtual assets represented in dollar terms, the proportion of the minable that fell to an all-time low of 52.7% at the end of May 2020 suffered fluctuations before reaching 70.0% on June 27 2021.

By contrast, daily trading volume of non-minable virtual assets that fell shy of or was similar to the level of the minable in the past has frequently exceeded that of minable assets by a large margin since early 2021. For instance, daily trading volume of non-minable assets stood at $372.5 billion, an all-time high as of April 18 2021. Although the minable also reported the highest daily trading volume of $229.1 billion on the same day, the difference between the two asset categories amounted to a whopping $143.4 billion.

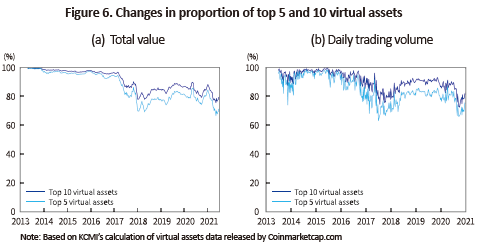

As for market concentration of virtual assets shown in Figure 6, the top 10 accounted for over 85.0% of the total volume of daily trading expressed in dollar terms, despite a continuous increase in the number of newly registered virtual assets. Also notable is the relatively small proportion of the lower-ranked five among the top 10 virtual assets. With the analysis scope widened to top 100, the top 10 represent over 95.0% of the aggregate value in dollar terms and the total volume of daily trading.

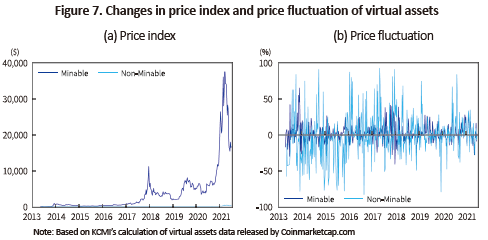

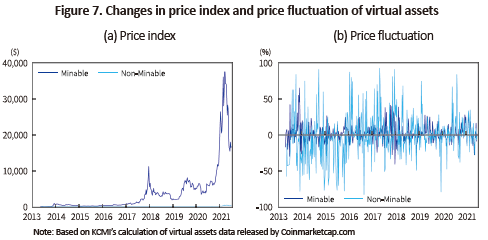

For a further analysis, this article categorized the top 100 by issuance method and calculated their weekly weighted average price index in dollar terms and price fluctuation for comparison. As shown in Figure 7, minable virtual assets have a remarkably higher price index but their price fluctuations are smaller, compared to the non-minable. It is also found that price indices for the minable and the non-minable move within the range of around ±50% and ±85%, respectively.

A close look at the trend of issuance and trading of virtual assets over the past eight years and three months reveals that virtual assets are regarded by the general public as an investment that can generate capital returns regardless of its purposes of original issuance or economic function, and is traded in the same manner as stocks. Notwithstanding such a trend, individuals investing in virtual assets should be keenly aware that around 40% of virtual assets have been deregistered and their prices show an incomprehensible pattern of fluctuations even for a single day. Particularly, retail investors need to take a sober assessment on whether the current virtual asset price is formed based on its intrinsic exchange value, utility value or underlying value.

* This article is based on recent data and some excerpts from the author’s previous research paper (2020).

1) For more details, please refer to ‘Five myths about cryptocurrency’, an article contributed by Professor Eswar Prasad of Cornell University to the May 20 2021 issue of the Washington Post.

2) For more details on each type, please refer to the research paper written by Kim. K.L. (2021).

3) Non-minable or pre-mined virtual assets are referred to as non-minable virtual assets hereinafter.

4) Virtual asset trades that were conducted through negotiated offering in the initial period are now primarily intermediated via competitive bidding (Ki,N.S., 2020; Bohme et al., 2015).

References

Ki, N.S., 2020, Legal Issues and Regulations for Virtual Asset Trading, Financial Law Research 17(1), 65-96.

Kim, K.L, 2021, Implications on Virtual Asset Investor Protection System in the US and EU, KCMI Issue Paper 21-13.

Lee, S.B., 2020, International Discussion and Policy Direction for Applying Securities Regulation to Virtual Assets, the 141 issue of KRX Market, 14-33.

Bohmem R., Christin, N., Edelman, B. and Moore, T., 2015, Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(2), 213–238.

Cuervo, C., Morozova, A., and Sugimono, N., 2019, Regulation of Crypto Assets, Fintech Note 19/03.

FATF, 2015, Virtual Currencies.

FATF, 2019, Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers.

FSB, 2018, Crypto-assets, Report to the G20 on work by the FSB and standard-setting bodies.

HM Treasury, FCA and Bank of England, 2018, Cryptoassets Taskforce: final report.

IOSCO, 2020, Issues, Risks and Regulatory Considerations Relating to Crypto-Asset Trading Platforms, FR02/2020.

Lyons, R. K. and Viswanath-Natraj, G., 2020, What Keeps Stablecoins Stable?, NBER Working Paper No. 27136.

Prasad, Eswar, 2021. 5. 20, Five myths about cryptocurrency, The Washington Post.

SEC, 2019, Framework for “Investment Contract” Analysis of Digital Assets.

Treasury Committee in House of Commons, 2018, Crypto-assets, Twenty-Second Report of Session 2017-19.

Definition and type of virtual assets

It has been agreed to use the terms such as virtual asset, cryptoasset and digital asset officially or internationally. Still, virtual currency, cryptocurrency or digital currency are widely used as terms representing virtual assets. However, there seem to be no virtual currencies, no cryptocurrencies, or no digital currencies that are counted as real money or currency. (Treasury Committee in House of Commons, 2018; Prasad, May 20 2021).

Although the functioning currencies are traditionally understood to serve as a store of value, a medium of exchange and a unit of account, even Bitcoin, the most prevailing virtual asset in the market, rarely performs all these functions. Furthermore, Bitcoin is usually perceived by the general public as an investment on which they could gain capital profits, and has been traded more actively than any other virtual assets. In line with this view, it seems more reasonable to recognize Bitcoin as a type of assets rather than a currency.

Such perception has been gaining ground since mid-2017. A case in point is that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) introduced the virtual currency concept in June 2014 in an effort to prevent virtual assets from being used for money laundering and terrorist financing, but in October 2018 decided to newly introduce the definition of a virtual asset and changed the previously used term of virtual currency into virtual asset (FATF, 2015; FATF, 2019).

In addition, the terms of virtual asset, cryptoasset and digital asset have been officially used by major economies including the US and the UK as well as international organizations such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) (Cuervo et al., 2019; FSB, 2018; HM Treasury et al., 2018; IOSCO, 2020; SEC, 2019). In Korea, a virtual asset was first defined as a legal term under the March 2020 amendment to the Act on Reporting and Using Specified Financial Transaction Information.

The definition and term representing a virtual asset vary slightly by country and international agency. The definition of a virtual asset by FATF is a ‘digital representation of value that can be digitally traded, transferred, or used for a purpose of payment or investment, excluding a digital representation of legal tender, securities and other financial assets’. On the other hand, IOSCO uses the term cryptoasset, instead of virtual asset, which falls into the definition of a form of private assets based on encryption or distributed ledger technology. The primary term employed by the UK is cryptoasset while the US refers to a virtual asset as a digital asset under the definition similar to IOSCO’s.

In accordance with Article 2 Paragraph 3 of the Korean Act on Reporting and Using Specified Financial Transaction Information, a virtual asset is defined as a digital token with economic value which can be digitally traded or transferred and all relevant rights. However, items whose disposal and use are limited by an issuer, tangible and intangible outcomes acquired via games, digital money, digital securities, and digital bills are excluded from virtual assets.

By the way, virtual assets can be classified into the categories of exchange token, utility token and security token depending on their own economic function and legal nature (HM Treasury et al., 2018).2) To put it more simply, an exchange token refers to a virtual asset issued to serve as a medium of exchange without imitations on its disposal or use, whereas a utility token means a virtual asset whose disposal is limited by an issuer and a security token represents a virtual asset that meets legal requirements of securities.

Current state of virtual asset issuance

A virtual asset was originally devised to serve as a means of payment in the peer-to-peer payment and settlement system (referred to as “P2P payment system”) underpinned by distributed ledger technology. For such use, the creator of the Bitcoin cryptocurrency known by a pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto designed Blockchain—the first and original form of distributed ledger—where a participant who first validates or conducts proof of work for authenticity of a transaction is given Bitcoin as rewards for their labor. This process was named ‘mining’ by Satoshi Nakamoto.

For Bitcoin to be mined or issued, it requires on-chain transactions in which Bitcoin is used as a means of payment in the P2P payment system. Otherwise, there would be no demand for proof of work and thus, Bitcoin mining never takes place. As such, a virtual asset issued through mining refers to a minable virtual asset.

However, not all virtual assets are issued via mining. There are other types such as non-minable and pre-mined virtual assets. For issuance, the non-minable is sold to a digital wallet holder belonging to the issuer’s distributed ledger network and then, is proven valid, while the pre-mined is pre-sold by its issuer for the purpose of raising capital from or getting sponsored by many unspecified individuals. For these reasons, the issuance of non-minable or pre-mined virtual assets are also referred to as token sales.3)

In general, an exchange token is issued via mining while the issuance of a utility token and a security token is characterized by being non-minable. However, some virtual assets known to act as exchange tokens are issued in a non-minable method. This may be due to lack of economic efficiency in the mining-based issuance, but it is largely attributable to the fact that a virtual asset cannot be issued unless it is widely used as a means of payment.

According to the analysis results of virtual asset data presented by Coinmarketcap.com, the number of virtual assets registered with exchanges around the world reached 8,950 during the period from April 27 2013 to June 27 2021. Among them, a total of 5,442 virtual assets remained registered as of June 27 2021. Given seven virtual assets already being registered and traded prior to April 27 2013, this indicates that 8,943 assets were newly registered (or issued) and 3,508 assets were deregistered or disappeared during the same period.

A close look at changes in virtual asset registrations categorized by issuance method reveals that much of virtual assets were primarily minable in the initial stage as shown in Figure 2. However, the non-minable has steeply increased since early 2017 up to present while the minable has shown a moderate downturn since mid-2018. As of June 27 2021, with 453 minable virtual assets being traded, the number of non-minable assets stood at 4,989, 11 times higher than that of the minable.

Current state of virtual asset trading

When an exchange token is traded as a medium of payment, the relevant trading data are entered in a digital wallet and the token is transferred to a third party. If its exchange value is neither in sync with the exchange value of legal tender issued by the central bank nor determined based on public consensus, the chances are slim for such a token to serve as a means of payment. This is because how an exchange token is accepted largely depends on the size of a group participating in exchange value assessment and the stability of exchange value.

An interesting fact is that most exchange tokens including Bitcoin rarely have a mechanism that determines their own exchange value. This implies that value of any exchange token can be discovered only after payment and settlement transactions via the token are repeatedly carried out without interruptions. Since the launch of the first virtual asset exchange on July 18 2010, exchange tokens have begun to trade through competitive bidding just as stocks do.4)

From then on, all forms of virtual assets have been traded and distributed under the competitive bidding system, regardless of types. For example, even a stablecoin whose mechanism makes its exchange value pegged to a certain level is being traded through competition bidding (Lyons and Viswanath-Natraj, 2020). Accordingly, the general public tend to recognize most virtual assets—irrespective of the purpose of issuance—as investments on which they can achieve capital returns.

As a result, virtual asset prices, like stock prices, have frequently changed on a daily basis, displaying much higher volatility than the stock market. This is especially evident in 2017 and 2020 when a surge in retail investors participating in virtual asset trades and their investment funds made virtual asset prices steeply rise in a short time span, thereby driving up the trading value to the extent incomparable to the previous level.

More concretely, Figure 5 shows that the total value of virtual assets in dollar terms sharply increased from early 2017 to early 2018 before showing a dramatic plunge. Since the outbreak of a global pandemic was officially declared in March 2020, the value has spiked again at an unprecedented pace, reaching a record peak of $2,543.9 billion in early May 2021 ($1,804.4 billion of the minable, $739.5 billion of the non-minable) and then plummeted until June 2021.

By contrast, daily trading volume of non-minable virtual assets that fell shy of or was similar to the level of the minable in the past has frequently exceeded that of minable assets by a large margin since early 2021. For instance, daily trading volume of non-minable assets stood at $372.5 billion, an all-time high as of April 18 2021. Although the minable also reported the highest daily trading volume of $229.1 billion on the same day, the difference between the two asset categories amounted to a whopping $143.4 billion.

As for market concentration of virtual assets shown in Figure 6, the top 10 accounted for over 85.0% of the total volume of daily trading expressed in dollar terms, despite a continuous increase in the number of newly registered virtual assets. Also notable is the relatively small proportion of the lower-ranked five among the top 10 virtual assets. With the analysis scope widened to top 100, the top 10 represent over 95.0% of the aggregate value in dollar terms and the total volume of daily trading.

* This article is based on recent data and some excerpts from the author’s previous research paper (2020).

1) For more details, please refer to ‘Five myths about cryptocurrency’, an article contributed by Professor Eswar Prasad of Cornell University to the May 20 2021 issue of the Washington Post.

2) For more details on each type, please refer to the research paper written by Kim. K.L. (2021).

3) Non-minable or pre-mined virtual assets are referred to as non-minable virtual assets hereinafter.

4) Virtual asset trades that were conducted through negotiated offering in the initial period are now primarily intermediated via competitive bidding (Ki,N.S., 2020; Bohme et al., 2015).

References

Ki, N.S., 2020, Legal Issues and Regulations for Virtual Asset Trading, Financial Law Research 17(1), 65-96.

Kim, K.L, 2021, Implications on Virtual Asset Investor Protection System in the US and EU, KCMI Issue Paper 21-13.

Lee, S.B., 2020, International Discussion and Policy Direction for Applying Securities Regulation to Virtual Assets, the 141 issue of KRX Market, 14-33.

Bohmem R., Christin, N., Edelman, B. and Moore, T., 2015, Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(2), 213–238.

Cuervo, C., Morozova, A., and Sugimono, N., 2019, Regulation of Crypto Assets, Fintech Note 19/03.

FATF, 2015, Virtual Currencies.

FATF, 2019, Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers.

FSB, 2018, Crypto-assets, Report to the G20 on work by the FSB and standard-setting bodies.

HM Treasury, FCA and Bank of England, 2018, Cryptoassets Taskforce: final report.

IOSCO, 2020, Issues, Risks and Regulatory Considerations Relating to Crypto-Asset Trading Platforms, FR02/2020.

Lyons, R. K. and Viswanath-Natraj, G., 2020, What Keeps Stablecoins Stable?, NBER Working Paper No. 27136.

Prasad, Eswar, 2021. 5. 20, Five myths about cryptocurrency, The Washington Post.

SEC, 2019, Framework for “Investment Contract” Analysis of Digital Assets.

Treasury Committee in House of Commons, 2018, Crypto-assets, Twenty-Second Report of Session 2017-19.