Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

A Comparative Look at the Impacts of Korean and US Policy Rate Hikes from the Perspective of Market Rates, and the Implications

Publication date Jul. 11, 2023

Summary

In the June FOMC, the US Fed halted its rate hike for the first time after March 2022. Given the recent inflation trends and economic conditions, both the US and Korea could have neared their end of their rate hike cycle. Against the backdrop, this article explored the impacts of both countries’ policy rate hikes on long-term government bond yields during this monetary tightening cycle.

During the recent rate hike cycle, the increase in US government bonds resulting from a series of policy rate hikes was evidently low as compared to Korea. The US saw Treasury yields rising much less than during their past rate hike cycles. This could imply a potential decrease in the impact of key rate hikes on Treasury yields. A major culprit behind this could be a recent phenomenon of the unprecedentedly low level of Treasury term premia in the aftermath of cumulative QE.

The Fed appears to maintain quantitative tightening while freezing its benchmark rate. QT–if prolonged–could weaken the cumulative effects of QE, and thus broaden term premia. Hence, it is necessary to pay attention to the changes in term premia as much as monetary policy as one of the determinants of Treasury yields. Treasury yields affect Korea via the term premium path. Even if both Korea and the US freeze their policy rate, a rise in US term premia could work as an upward factor for Korea’s government bond yields. It is worth noting that an increase in US term premia could limit the effectiveness of domestic monetary policy. Furthermore, the diminished impact of the US policy rate on long-term interest rates is believed to have contributed to the widening rate reversal between Korea and the US. The fact that the primary cause behind the rate reversal lies in the US means greater hardship for Korea's monetary policy responses. This requires Korea to come up with ways to cope with a potential rise in exchange rate volatility.

During the recent rate hike cycle, the increase in US government bonds resulting from a series of policy rate hikes was evidently low as compared to Korea. The US saw Treasury yields rising much less than during their past rate hike cycles. This could imply a potential decrease in the impact of key rate hikes on Treasury yields. A major culprit behind this could be a recent phenomenon of the unprecedentedly low level of Treasury term premia in the aftermath of cumulative QE.

The Fed appears to maintain quantitative tightening while freezing its benchmark rate. QT–if prolonged–could weaken the cumulative effects of QE, and thus broaden term premia. Hence, it is necessary to pay attention to the changes in term premia as much as monetary policy as one of the determinants of Treasury yields. Treasury yields affect Korea via the term premium path. Even if both Korea and the US freeze their policy rate, a rise in US term premia could work as an upward factor for Korea’s government bond yields. It is worth noting that an increase in US term premia could limit the effectiveness of domestic monetary policy. Furthermore, the diminished impact of the US policy rate on long-term interest rates is believed to have contributed to the widening rate reversal between Korea and the US. The fact that the primary cause behind the rate reversal lies in the US means greater hardship for Korea's monetary policy responses. This requires Korea to come up with ways to cope with a potential rise in exchange rate volatility.

While Korea's policy rate has remained unchanged since February 2023, the Fed halted its rate hike in June for the first time since March 2022. What this suggests is that there may be one or two more policy rate hikes this year. However, Korea and the US could have come near to their end of the rate hike cycle given their inflation and real economic conditions. Monetary policy affects the economy and financial markets via various paths, one of which is to trigger a change in mid- to long-term market rates (financing conditions) for adjusting excessive demand (business cycles). From that perspective, the impact of a key rate change on mid- to long-term government bond yields (risk-free rate) could be a start of the monetary policy path. This article explores the impact of policy rate hikes by the US and Korea on their long-term government bond yields during this monetary tightening cycle, and discusses the implications.

Post-pandemic changes in US and Korean policy rates and government bond yields

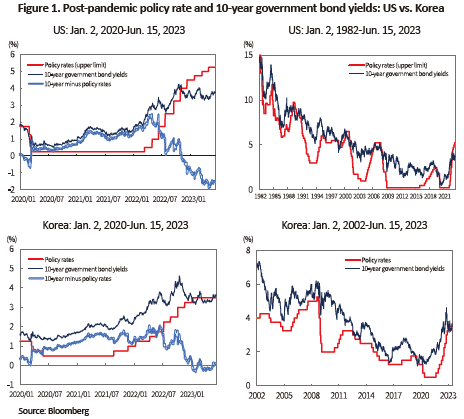

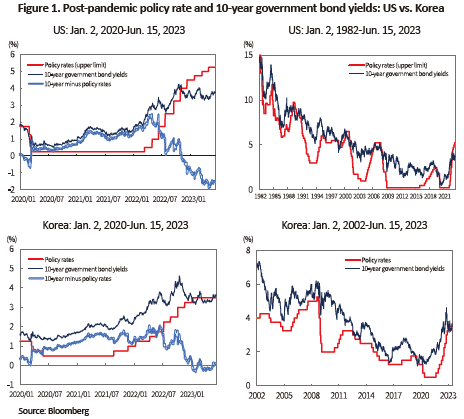

From the view of the impact on long-term interest rates, the most distinctive difference between Korea and the US lies in the level of increases in government bond yields vis-a-vis the size of policy rate hikes. For a more concrete look, I compared the average government bond yields of both countries during the period of one month prior to the first and the most recent rate hikes. First of all, the US policy rate finally reached 5.25% in May 2023 since the first hike from 0.25% to 0.5% in March 2022. During the corresponding period, US Treasury yields increased from 1.93% (the February average) to 3.46% (the April average). In short, a 5.0 percentage point increase in the US policy rate led to a 1.53 percentage point increase in US Treasury yields. By contrast, Korea's policy rate climbed all the way to 3.5% in January 2023 since its first hike from 0.5% to 0.75% at the end of August 2022. However, this caused Korean government bond yields to rise by 1.67 percentage points from 1.89% to 3.59%. While the US rate hike was 2 percentage points higher than Korea's, the size of yield increases in Korea surpassed that in the US.

The changes in US Treasury yields during this rate hike cycle were unprecedented compared to the country's own past records. Figure 1 confirms that Treasury yields rose to the level similar to the final policy rate during rate hike cycles since 1982. By contrast, the peak of government bond yields (4.24% on Oct. 24, 2022) was far below the final1) policy rate (5.25% in May 2023) in the recent cycle. Korea's data on rate hike cycles since 2002 also show a similar trend: Its government bond yield peaks were formed higher than final policy rate levels. Unlike the US, however, Korea saw its government bond yield peak (4.62% on Oct. 21, 2022) go well beyond the final policy rate of 3.5% in the recent rate hike cycle. Those findings mean that in order to trigger the same level of increases in long-term government bond yields with monetary policy, the US needs to hike its policy rate more as compared to Korea. Moreover, it is believed that long-term rates’ sensitivity to policy rate hikes have abated significantly in the US. What those findings imply is that the central bank's policy rate hike may not lead to the intended monetary tightening effect.2)

Decomposing government bond yields for monetary policy impacts in the US and Korea

This section explores the differences in the impacts of Korean and US monetary policy by decomposing the determinants of government bond yields. According to the theory of interest rate determination, government bond yields consist of the sum of the expected future short-term rate (policy rate) and the term premium. The former is called risk-neutral yields, which can be understood as a part of government bond yields reflecting the effect of a rate hike. The term premium–the risk premium of bonds–is determined by various factors: It increases when the perceived risk of rising government bond yields (interest rate volatility) by investors goes up. Roughly speaking, the risk of rate hikes is determined by monetary policy, inflation, and the real economy. Hence, the higher uncertainty of those factors, the larger the term premium. Another factor affecting term premia includes demand and supply for bonds. It is known that in the case of the US, QE influenced the structural decline of term premia (Bernanke, 2015).

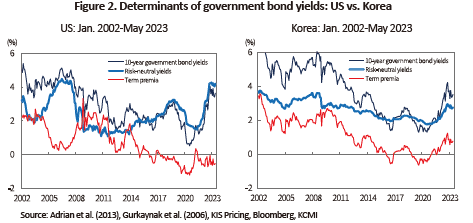

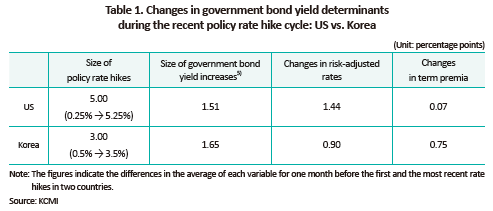

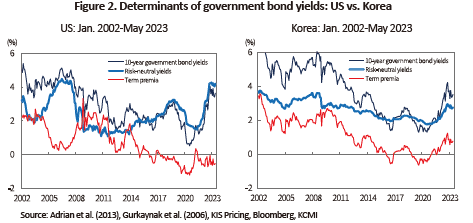

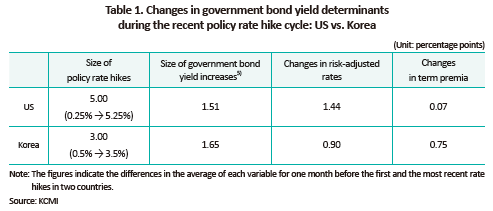

Figure 2 adopted the method presented by Adrian et al. (2013) for decomposing the 10-year government bond yield into monetary policy expectations (risk-neutral yields) and term premia. Table 1 shows the result of analysis based on the method mentioned in the previous section, summing up the changes in government bond yield determinants during the recent rate hike cycle. As shown in Table 1, it is confirmed that the difference across countries in the impact of policy rate hikes on government bond yield increases lies in the changes in term premia.3) Both countries saw a similar level of changes in risk-neutral yields due to rate hikes (reflecting rate hike expectations), while their level of changes in term premia varies widely. The term premium accounted for 45% (=0.75/1.65) of the increase in government bond yields in Korea. However, the US term premium expanded only 7bp, indicating that the rise in government bond yields was solely driven by risk-neutral yields.4) Figure 2 shows that from 2020 until recently, US term premia have remained at the lowest level since the 1970s. Given the high inflation and the resulting uncertainty in monetary policy during the recent rate hike cycle, it is quite unprecedented to see the US term premium to remain in that low level.

The reasons for the unprecedentedly low level of US term premia in recent years have not yet been rigorously examined. Part of the reasons could be that amid the Fed's steepest policy rate hike since the 1980s, policy rates have disproportionately become the focus of interest as a key factor driving changes in Treasury yields. Based on the findings in this article, it is worth taking into account the followings. Figure 2 confirms a significant upward trend in Korea's term premia since 2020, unlike the US ones. Hence, the behavior found in US term premia appears to have stemmed from many US-specific factors, among which cumulative QE effects are presumed to be one of the most likely causes.6)

Implications

The findings presented in this article has ample implications in several aspects. This section explores the implications for the US first, and then Korea. Among others, there is a need for renewed interest in term premia as a Treasury yield determinant. In the June FOMC, the Fed froze the policy rate, hinting a possibility of pausing its rate hike in a foreseeable future. Until a rate cut is materialized, it is possible policy rates to lose its influence as a determinant to government bond yields. While the Fed froze the policy rate, its QT is still ongoing. Therefore, term premia could be normalized by QT even if the policy rate remains frozen. Going forward, term premia could possibly serve as a factor either driving an increase or limiting a decrease in government bond yields.

Despite the Fed's steep policy rate hikes, the real economy in the US is reported to have been in better shape than expected (Kang, 2023: Song et al., 2023). This is attributable to a wide array of factors and interpretations, but the decreased impact of policy rates on determining government bond yields could have played an important role given that the path of a rate hike shaping the real economy starts at the rise in mid- to long-term government bond yields. This needs to be taken into account in the Fed's assessment on the strength of tightening resulting from policy rate levels.

Treasury yields affect Korean government bonds via the term premium path.7) If US term premia are normalized, this could serve as an important factor in raising Korean government bond yields. This could possibly limit the effectiveness of Korea's monetary policy, which requires careful attention. In addition, it may be the case that the diminished impact of Fed rate hikes on mid- to long-term Treasury yields played a role in the reversal of Korean and US policy rates (and other short-term rates linked to the policy rate). Of course, it could be argued that the rate reversal could primarily be attributed to stronger inflation in the US as compared to Korea. There is also a possibility that the reversal exacerbated further partly because the size of the rate hike for triggering a certain level of tightening could be larger in the US as compared to Korea. The fact that the primary cause behind the rate reversal lies in the US means greater hardship for Korea's monetary policy responses. It is recommended that Korea come up with ways to cope with the potential risk of a rise in foreign exchange volatility.

1) As mentioned earlier, it is possible for the US to increase its policy rate one or two times more this year.

2) The strength of QT can be seen in the policy rate gap, which is the policy rate minus the (short-term) neutral rate. The larger the policy rate–that is, the policy rate is higher than the (short-term) neutral rate, the more tightening monetary policy can be viewed (Baek and Jang, 2022). The (short-term) neutral rate means the policy rate level that fits economic fundamentals. Under the same context, we can get the long-term neutral rate and the long-term rate gap (the long-term rate minus the long-term neutral rate). The findings in this article suggest a possibility that a certain level of the policy rate gap now leads to a lower level of the long-term rate gap compared to the past. Also predictable is that we can't rule out the possibility where Korea's policy rate–even if it's lower than the US rate–could lead to monetary tightening by measure of the long-term rate gap to a stronger extent than in the US.

3) In Table 1, a policy rate increase of 1 percentage points led to pushing up the risk-neutral yield by 0.3 percentage points both in the US and Korea. But the figure cannot be generalized because the result may vary depending on the estimation period and other factors in the Adrian et al. (2013) model.

4) For convenience, Figure 2 shows term premia since 2002 only. US term premia can be also found on the New York Fed website.

5) The government bond yields in the table are from the model in Adrian et al. (2013), and are slightly different from actual yields data.

6) Numerous studies including Krishnamurthy & Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) and Bernanke (2016) found that the Fed's post-crisis QE has contributed to lowering the level of Treasury yields. The size of QE could be estimated from the size of Fed holdings, which ballooned in its response to the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. The overall Fed holdings (Treasury securities) soared from $4.2 trillion ($2.4 trillion) in January 2020 to $8.9 trillion ($5.8 trillion) in May 2022 Together with the moves to raise the policy rate, the Fed has been undertaking QT and shrinking its balance sheet since June. However, due to the cumulative magnitude, overall Fed holdings (Treasury securities) still stood at $8.5 trillion ($5.2 trillion). For comparison, the Fed used to hold only less than $1 trillion during the period between 2003 and QE.

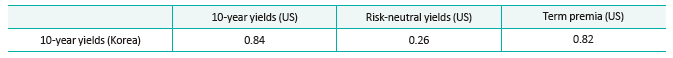

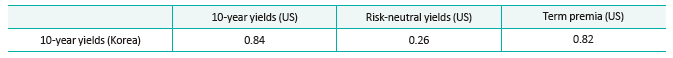

7) The table below shows the correlation between the determinants of 10-year yields of Korean and US government bonds based on month-end data between January 2002 and May 2023.

References

Adrian, T., Crump, R., Moench, E., 2013, Pricing term structure with linear regression, Journal of Financial Economics 110(1), 110-138.

Bernanke, B.S., 2016, Why are interest rates so low, part 4: Term premiums, Brookings.

Gurkaynak, R.S., Sack, B., Wright, J.H., 2006, The U.S. treasury yield curve: 1961 to present, FRB Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2006-28.

Krishnamurthy, A., Vissing-Jorgensen, A., 2011, The effects of quantitative easing on interest rates: Channels and implications for policy, NBER Working Paper 17555.

(Korean)

Kang, H. J., 2013, Declining interest rate sensitivity of the US real economy and its implications, KCMI Opinion 2023-12, KCMI.

Baek, I. S., and Jang, B. S., 2022, Assessment of the Fed’s monetary policy and its implications for interest rates in Korea, Issue Paper 22-08, KCMI.

Song, B. H., et al., 2023, How to understand the enigmatic American economy, Bank of Korea.

Post-pandemic changes in US and Korean policy rates and government bond yields

From the view of the impact on long-term interest rates, the most distinctive difference between Korea and the US lies in the level of increases in government bond yields vis-a-vis the size of policy rate hikes. For a more concrete look, I compared the average government bond yields of both countries during the period of one month prior to the first and the most recent rate hikes. First of all, the US policy rate finally reached 5.25% in May 2023 since the first hike from 0.25% to 0.5% in March 2022. During the corresponding period, US Treasury yields increased from 1.93% (the February average) to 3.46% (the April average). In short, a 5.0 percentage point increase in the US policy rate led to a 1.53 percentage point increase in US Treasury yields. By contrast, Korea's policy rate climbed all the way to 3.5% in January 2023 since its first hike from 0.5% to 0.75% at the end of August 2022. However, this caused Korean government bond yields to rise by 1.67 percentage points from 1.89% to 3.59%. While the US rate hike was 2 percentage points higher than Korea's, the size of yield increases in Korea surpassed that in the US.

Decomposing government bond yields for monetary policy impacts in the US and Korea

This section explores the differences in the impacts of Korean and US monetary policy by decomposing the determinants of government bond yields. According to the theory of interest rate determination, government bond yields consist of the sum of the expected future short-term rate (policy rate) and the term premium. The former is called risk-neutral yields, which can be understood as a part of government bond yields reflecting the effect of a rate hike. The term premium–the risk premium of bonds–is determined by various factors: It increases when the perceived risk of rising government bond yields (interest rate volatility) by investors goes up. Roughly speaking, the risk of rate hikes is determined by monetary policy, inflation, and the real economy. Hence, the higher uncertainty of those factors, the larger the term premium. Another factor affecting term premia includes demand and supply for bonds. It is known that in the case of the US, QE influenced the structural decline of term premia (Bernanke, 2015).

Figure 2 adopted the method presented by Adrian et al. (2013) for decomposing the 10-year government bond yield into monetary policy expectations (risk-neutral yields) and term premia. Table 1 shows the result of analysis based on the method mentioned in the previous section, summing up the changes in government bond yield determinants during the recent rate hike cycle. As shown in Table 1, it is confirmed that the difference across countries in the impact of policy rate hikes on government bond yield increases lies in the changes in term premia.3) Both countries saw a similar level of changes in risk-neutral yields due to rate hikes (reflecting rate hike expectations), while their level of changes in term premia varies widely. The term premium accounted for 45% (=0.75/1.65) of the increase in government bond yields in Korea. However, the US term premium expanded only 7bp, indicating that the rise in government bond yields was solely driven by risk-neutral yields.4) Figure 2 shows that from 2020 until recently, US term premia have remained at the lowest level since the 1970s. Given the high inflation and the resulting uncertainty in monetary policy during the recent rate hike cycle, it is quite unprecedented to see the US term premium to remain in that low level.

Implications

The findings presented in this article has ample implications in several aspects. This section explores the implications for the US first, and then Korea. Among others, there is a need for renewed interest in term premia as a Treasury yield determinant. In the June FOMC, the Fed froze the policy rate, hinting a possibility of pausing its rate hike in a foreseeable future. Until a rate cut is materialized, it is possible policy rates to lose its influence as a determinant to government bond yields. While the Fed froze the policy rate, its QT is still ongoing. Therefore, term premia could be normalized by QT even if the policy rate remains frozen. Going forward, term premia could possibly serve as a factor either driving an increase or limiting a decrease in government bond yields.

Despite the Fed's steep policy rate hikes, the real economy in the US is reported to have been in better shape than expected (Kang, 2023: Song et al., 2023). This is attributable to a wide array of factors and interpretations, but the decreased impact of policy rates on determining government bond yields could have played an important role given that the path of a rate hike shaping the real economy starts at the rise in mid- to long-term government bond yields. This needs to be taken into account in the Fed's assessment on the strength of tightening resulting from policy rate levels.

Treasury yields affect Korean government bonds via the term premium path.7) If US term premia are normalized, this could serve as an important factor in raising Korean government bond yields. This could possibly limit the effectiveness of Korea's monetary policy, which requires careful attention. In addition, it may be the case that the diminished impact of Fed rate hikes on mid- to long-term Treasury yields played a role in the reversal of Korean and US policy rates (and other short-term rates linked to the policy rate). Of course, it could be argued that the rate reversal could primarily be attributed to stronger inflation in the US as compared to Korea. There is also a possibility that the reversal exacerbated further partly because the size of the rate hike for triggering a certain level of tightening could be larger in the US as compared to Korea. The fact that the primary cause behind the rate reversal lies in the US means greater hardship for Korea's monetary policy responses. It is recommended that Korea come up with ways to cope with the potential risk of a rise in foreign exchange volatility.

1) As mentioned earlier, it is possible for the US to increase its policy rate one or two times more this year.

2) The strength of QT can be seen in the policy rate gap, which is the policy rate minus the (short-term) neutral rate. The larger the policy rate–that is, the policy rate is higher than the (short-term) neutral rate, the more tightening monetary policy can be viewed (Baek and Jang, 2022). The (short-term) neutral rate means the policy rate level that fits economic fundamentals. Under the same context, we can get the long-term neutral rate and the long-term rate gap (the long-term rate minus the long-term neutral rate). The findings in this article suggest a possibility that a certain level of the policy rate gap now leads to a lower level of the long-term rate gap compared to the past. Also predictable is that we can't rule out the possibility where Korea's policy rate–even if it's lower than the US rate–could lead to monetary tightening by measure of the long-term rate gap to a stronger extent than in the US.

3) In Table 1, a policy rate increase of 1 percentage points led to pushing up the risk-neutral yield by 0.3 percentage points both in the US and Korea. But the figure cannot be generalized because the result may vary depending on the estimation period and other factors in the Adrian et al. (2013) model.

4) For convenience, Figure 2 shows term premia since 2002 only. US term premia can be also found on the New York Fed website.

5) The government bond yields in the table are from the model in Adrian et al. (2013), and are slightly different from actual yields data.

6) Numerous studies including Krishnamurthy & Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) and Bernanke (2016) found that the Fed's post-crisis QE has contributed to lowering the level of Treasury yields. The size of QE could be estimated from the size of Fed holdings, which ballooned in its response to the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. The overall Fed holdings (Treasury securities) soared from $4.2 trillion ($2.4 trillion) in January 2020 to $8.9 trillion ($5.8 trillion) in May 2022 Together with the moves to raise the policy rate, the Fed has been undertaking QT and shrinking its balance sheet since June. However, due to the cumulative magnitude, overall Fed holdings (Treasury securities) still stood at $8.5 trillion ($5.2 trillion). For comparison, the Fed used to hold only less than $1 trillion during the period between 2003 and QE.

7) The table below shows the correlation between the determinants of 10-year yields of Korean and US government bonds based on month-end data between January 2002 and May 2023.

References

Adrian, T., Crump, R., Moench, E., 2013, Pricing term structure with linear regression, Journal of Financial Economics 110(1), 110-138.

Bernanke, B.S., 2016, Why are interest rates so low, part 4: Term premiums, Brookings.

Gurkaynak, R.S., Sack, B., Wright, J.H., 2006, The U.S. treasury yield curve: 1961 to present, FRB Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2006-28.

Krishnamurthy, A., Vissing-Jorgensen, A., 2011, The effects of quantitative easing on interest rates: Channels and implications for policy, NBER Working Paper 17555.

(Korean)

Kang, H. J., 2013, Declining interest rate sensitivity of the US real economy and its implications, KCMI Opinion 2023-12, KCMI.

Baek, I. S., and Jang, B. S., 2022, Assessment of the Fed’s monetary policy and its implications for interest rates in Korea, Issue Paper 22-08, KCMI.

Song, B. H., et al., 2023, How to understand the enigmatic American economy, Bank of Korea.