Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Current Status and Challenges of KOFR Adoption: The Importance of KOFR-Linked Bonds and Loans

Publication date Jan. 14, 2025

Summary

Korea's benchmark rate reform has reached a critical turning point. The Benchmark Rates and Short-Term Money Market Council, a public-private collaborative body, has established a phased transition plan to expand the use of KOFR (Korea's Risk-Free Reference Rate), beginning with derivatives transactions in 2025. Since adopting RFRs in derivatives markets has been a cornerstone of global benchmark rate reforms, this roadmap marks a significant milestone in Korea’s reform efforts.

Although financial authorities and institutions in Korea have reached a consensus on transitioning the reference rate for derivatives to KOFR, the broader adoption of KOFR for cash products—such as bonds and loans, which are vital to the financing activities of households and corporations—remains insufficiently explored. Evidence from major economies and related studies emphasize the potential advantages of Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) linked to KOFR. Compared to CD rate-linked FRNs, KOFR-based FRNs could offer issuers reduced funding costs while providing investors with enhanced price stability, creating mutual benefits for both parties.

The adoption of RFRs in loan markets varies considerably across jurisdictions. Korea’s loan market is unique in its exclusive reliance on reference rates that reflect banks' funding costs, a structure rarely observed in major economies. This system systematically transfers funding cost risks from banks to retail borrowers, raising concerns about both financial stability and consumer protection. To address these issues, KOFR should be adopted as the lending reference rate for certain retail borrowers, particularly self-employed individuals and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This reform would contribute to the establishment of a benchmark rate regime that improves risk-sharing structure between banks and borrowers, while also supporting funding of vulnerable borrowers.

Although financial authorities and institutions in Korea have reached a consensus on transitioning the reference rate for derivatives to KOFR, the broader adoption of KOFR for cash products—such as bonds and loans, which are vital to the financing activities of households and corporations—remains insufficiently explored. Evidence from major economies and related studies emphasize the potential advantages of Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) linked to KOFR. Compared to CD rate-linked FRNs, KOFR-based FRNs could offer issuers reduced funding costs while providing investors with enhanced price stability, creating mutual benefits for both parties.

The adoption of RFRs in loan markets varies considerably across jurisdictions. Korea’s loan market is unique in its exclusive reliance on reference rates that reflect banks' funding costs, a structure rarely observed in major economies. This system systematically transfers funding cost risks from banks to retail borrowers, raising concerns about both financial stability and consumer protection. To address these issues, KOFR should be adopted as the lending reference rate for certain retail borrowers, particularly self-employed individuals and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This reform would contribute to the establishment of a benchmark rate regime that improves risk-sharing structure between banks and borrowers, while also supporting funding of vulnerable borrowers.

As major economies have completed their benchmark rate reforms, Korea has also intensified efforts to reduce its reliance on the existing CD rate and establish the Korea Overnight Financing Repo Rate (KOFR)—Korea's Risk-Free Reference Rate (RFR) as the central benchmark rate. Korea’s benchmark rate reform is being spearheaded by the Benchmark Rates and Short-Term Money Market Council (hereafter referred to as “the Council”), comprising financial authorities and institutions. In August 2024, the Council declared its principle of transitioning Korea’s benchmark rate system to a KOFR-centered regime.1) Subsequently, in December, the Council unveiled a detailed roadmap to expand the application of KOFR, starting with derivatives transactions.2)

Financial transactions referencing benchmark rates can be broadly categorized into interest rate derivatives and cash transactions. In line with global practices, consensus has been reached in Korea to replace the reference rate for interest rate derivatives with KOFR. However, efforts to promote KOFR adoption in cash products—such as Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) and loans—remain limited. These products play a crucial role in the funding activities of various economic participants, underscoring their importance. This study briefly examines the Council’s roadmap for KOFR activation and highlights the need to foster the development of KOFR-linked bond and loan markets.

Key elements of the roadmap for promoting KOFR adoption

The Council has developed a timeline to implement KOFR in derivatives and bond markets starting in 2025. The roadmap focuses on gradually mandating KOFR-linked swaps, which are a key component of the interest rate derivatives market. Starting in July 2025, financial institutions with a nominal CD swap trading volume exceeding KRW 25 trillion over the previous 12 months will be required to execute a certain percentage of their new interest rate swap transactions as KOFR swaps.3) The recommended ratio will start at 10% in 2025 and increase by 10 percentage points each year, aiming to expand the share of KOFR swaps to over 50% of the total interest rate swaps market by 2030. Additionally, to support the smooth adoption of KOFR by financial institutions, the Korea Exchange plans to introduce central clearing for KOFR swap transactions starting in October 2025.

The transition from Inter-Bank Offered Rates (IBORs)—such as LIBOR and Korea's CD rates—to RFRs represents a cornerstone of global benchmark rate reforms. Within this context, the Council’s roadmap is significant as it aligns Korea’s reform efforts with global standards. The interest rate derivatives market is strongly influenced by liquidity externalities associated with benchmark rates, making it challenging for individual financial institutions to adopt new benchmark rates. Recognizing this aspect, major economies have introduced the “RFR First Initiative” to facilitate the adoption of RFRs in derivatives transactions. The introduction of mandatory KOFR-linked swaps under the Council’s roadmap mirrors these global initiatives. KOFR-linked swaps provide an effective mechanism for managing interest rate risks in a variety of KOFR-referenced financial transactions. As such, they are expected to play a pivotal role in the KOFR-centered benchmark rate ecosystem in Korea.

The Council also aims to expand the issuance of KOFR-linked Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) through public financial institutions, including the Korea Development Bank (KDB), the Industrial Bank of Korea (IBK), and the Export-Import Bank of Korea, as well as commercial banks. In 2024, public financial institutions in Korea issued KOFR-linked FRNs totaling KRW 800 billion. Beginning in 2025, the Council mandates that public financial institutions and commercial banks allocate at least 10% of their annual FRN issuance to KOFR-linked bonds, with a plan to gradually increase this proportion in subsequent years. This strategy parallels approaches adopted in major economies, where public financial institutions initially established RFR-linked FRN markets, enabling commercial banks to expand the market base and paving the way for non-bank financial institutions and corporations to participate in RFR-linked FRN issuance.

However, there are divergent opinions among market participants regarding the necessity of KOFR-linked FRNs in Korea. Furthermore, while the Council is expected to address the application of KOFR to loans in the future, a concrete plan for its implementation has yet to be developed. The following sections examine the economic characteristics of KOFR and its application to financial transactions in comparison with CD rates, and discuss the features of KOFR-linked FRNs and loans.

RFR (KOFR) vs. IBOR (CD rate)

RFRs and IBORs have distinct characteristics in various aspects. The primary distinction between them lies in their underlying economic substance. RFRs represent risk-free interest rates, while IBORs measure the average unsecured funding costs for banks. The inclusion of the funding cost risks of banks has been a key driver in creating the IBOR-centered ecosystem. By using IBORs as reference rates for loans, banks can transfer the risk of rising funding costs to borrowers. However, this also suggests that if banks’ credit risk increases, borrowers face higher borrowing costs, underscoring the need to hedge this risk through interest rate swaps and other instruments.

Second, RFRs and IBORs exhibit fundamental differences in their relationship with economic cycles. The RFR reflects the risk-free market rates and thus tends to behave pro-cyclically, while the IBOR is counter-cyclical because it incorporates banks' credit risks. This results in a weaker correlation between IBORs and monetary policy changes, compared to RFRs. In particular, in economic downturns or financial crises, central banks may lower policy rates to reduce market interest rates. However, the excessive reliance on IBORs in the economy and financial markets could undermine these efforts, pushing up the funding costs for economic agents.

Third, these benchmark rates differ in their interest rate determination mechanisms. IBORs, as forward-looking term rates, enable interest payments to be calculated in advance for loans and bonds. In contrast, RFRs are backward-looking overnight rates, making it impossible to determine interest payments in advance. The application of RFRs to financial transactions is categorized into two primary methods based on the timing of interest determination: the set in-arrears method and the set in-advance method. Under the set in-arrears approach, the interest rate is calculated near the end of the interest period.4) It is based on the simple or compounded average of daily RFRs over the interest period. Major economies, such as the US and the UK, predominantly use this approach for RFR-linked FRNs. On the other hand, the set in-advance approach applies an averaged RFR from a prior period to the current interest period. For instance, if an interest payment is due 3 months from now, the set in-advance method would apply the average RFR from the previous 3 months. While this approach does not reflect actual interest rate fluctuations during the interest period, it offers the advantage of allowing borrowers to know their payment amounts in advance. Major economies employ both approaches for RFR-linked loans, depending on the specific transaction or market preferences.

Characteristics of RFR FRNs

Initially, FRNs using RFRs as reference rates, unlike LIBOR-linked FRNs, were expected to pose challenges to financial markets due to the delayed determination of interest rates. However, in major economies such as the US and the UK, RFRs have rapidly been adopted as the standard reference rate for FRNs, driven by market forces.5) This swift adoption can be attributed to the following advantages that RFR-linked FRNs, utilizing the set in-arrears approach, provide to both issuers and investors compared to IBOR-linked FRNs.

First, for investors, a key advantage of RFR-linked FRNs is that bond prices exhibit significantly low sensitivity to changes in the RFR, also referred to as duration risk. The duration of an FRN is determined by the interval between interest rate resets. For example, an FRN referencing a 3-month IBOR has a duration of 3 months.6) In contrast, RFR-linked FRNs using the set in-arrears approach fully incorporate daily changes of the RFR into the interest rate determination. This results in the price of the FRN unaffected by the RFR fluctuations. This low duration risk offers significant benefits for money market funds (MMFs), which are key investors in the FRN market. In the US, Europe, and Korea, MMFs are subject to regulatory limits on the total interest rate risk of portfolio holdings, such as the weighted average maturity (WAM) or duration. In calculating the WAM for FRNs, the interest rate reset period can be used as the maturity.7) Therefore, RFR-linked FRNs with a one-day interest rate reset period under the set in-arrears method are highly beneficial for MMFs in complying with WAM regulatory requirements.

Second, recent studies indicate that when the same company issues FRNs referencing SOFR, the U.S. dollar RFR, the financing rate is significantly lower compared to LIBOR-linked FRNs.8) This phenomenon, referred to as the “SOFR discount,” is attributed to the premium formed by the higher price stability offered by SOFR-linked FRNs.

In summary, while RFR-linked FRNs using the set in-arrears approach involve the inconvenience of delayed interest determination, they offer compensatory benefits such as higher price stability and regulatory advantages for MMFs. These characteristics contribute to lower financing costs for FRN issuers. Notably, companies that issue FRNs typically operate dedicated treasury departments, enabling them to manage cash flows effectively even without predetermined interest rates. Given these factors, RFR-linked FRNs are considered to provide economic benefits to both issuers and investors compared to IBOR-linked FRNs.

Characteristics of RFR loans

The application of benchmark rates to loans varies across jurisdictions depending on various factors such as the continuity of IBORs, legal frameworks (particularly those related to consumer protection and fair trade), and borrower preferences. In Japan and the Eurozone, IBORs—TIBOR in Japan and EURIBOR in the Eurozone—remain in use and continue to serve as the primary reference rates for loans. In contrast, the discontinuation of LIBOR in the US, the UK, and Switzerland has resulted in the wide use of RFRs as benchmark rates for loans.

Compared to other financial transactions, the application of RFRs to loans has faced greater challenges during the benchmark rate reform processes in major economies. When loans are referenced to RFRs, banks are required to manage on their own the basis risk—the mismatch between asset and liability reference rates—or the funding cost risks that were previously transferred to borrowers. For this reason, some banks and academics have raised concerns that in economies where loan reference rates, such as RFRs, do not reflect banks' funding costs, credit creation by banks could decline, and borrowing costs for economic agents might increase compared to scenarios where IBOR-linked loans remain available.9) However, evidence from the US, the UK, and Switzerland suggests that retail borrowers tend to prefer RFR-linked loans. Additionally, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and other financial authorities have evaluated the pro-cyclical nature of RFRs as a potential contributor to consumer protection in financial markets. Central banks have also expressed the view that RFR-linked loans are more suitable than IBOR-linked loans for enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy.10)

Therefore, it is important to monitor the macroeconomic effects of RFR-linked loans in the US, the UK, and Switzerland. However, regardless of whether IBORs remain in use, it is worth noting that major economies, particularly for retail loans, often use reference rates that do not include banks' credit risks, such as RFRs, central bank policy rates, and government bond yields.11)

Current state and implications in Korea

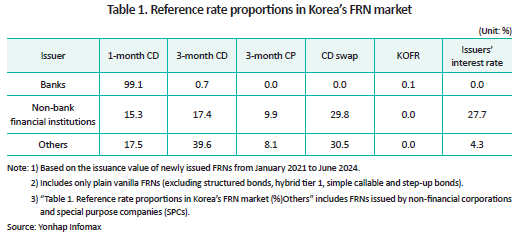

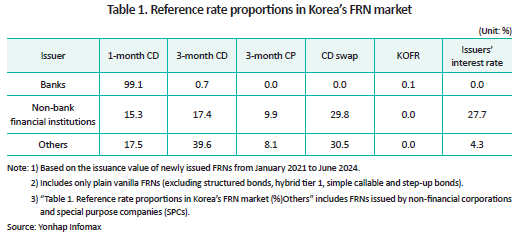

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of reference rates used in the domestic FRN market. In Korea, a variety of institutions—including banks, non-bank financial institutions, and corporations—issue FRNs. The primary reference rates used in the market include 1-month and 3-month CD rates, CD swap rates, and CP rates. Notably, banks, which are the largest issuers of FRNs in the domestic market, often use the 1-month CD rate as the reference rate instead of the 3-month CD rate. This preference appears to be driven by MMFs, the key investors in FRNs, which favor shorter-term CD rates to comply with WAM regulations.

However, unlike major economies, Korea has yet to designate the maturity of KOFR-linked FRNs as one day under WAM regulations. Moving forward, regulatory adjustments should be made to create an environment where the economic advantages of KOFR-linked FRNs can be fully realized, enabling various FRN issuers, including banks, to benefit from the “KOFR discount.”

As observed in major economies, the application of KOFR to loans is likely to face greater challenges compared to its implementation in derivatives or bond markets. Nevertheless, KOFR-linked loans hold significant potential to stabilize the lending market and support financing for vulnerable groups, including self-employed individuals and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Given these benefits, it is worth considering introducing KOFR loans from a macroeconomic perspective.

As shown in Table 2, the primary reference rates for loans used by banks in Korea all incorporate their funding costs. This structure, which is rarely observed in major economies, systematically transfers the risk of banks’ funding costs to retail borrowers, leading to the following implications.

First, the current system enables banks to avoid bearing basis risk arising from their loan transactions. This structure effectively facilitates lending activities. Second, from a financial stability perspective, IBOR-linked loans—such as those referencing CD rates—are beneficial only if borrowers can effectively manage the borrowing rate risks transferred from banks.12) While large corporations are generally equipped to manage such risks using instruments like CD swaps, households and SMEs typically lack the financial tools and expertise to do so. Therefore, the current lending regime, which transfers banks’ funding cost risks to households and SMEs, warrants careful reassessment. Third, in this environment, the price of loans should be determined to ensure transparency and efficiency. As shown in Table 2, however, the diversity of loan reference rates in Korea makes it complicated for retail borrowers to compare and evaluate the price of loans across banks.

In conclusion, KOFR should be adopted as the reference rate for loans targeting specific retail borrowers, such as the self-employed and SMEs, to encourage banks to directly manage their funding cost risks. This change could help establish a benchmark rate regime that fosters a more balanced risk-sharing structure between banks and borrowers while supporting vulnerable groups in their financing needs. Additionally, concerns raised in the US and other countries regarding potential reductions in credit creation due to RFR-linked loans are less relevant in the Korean context, where only IBOR-linked loans are currently in use.

1) Financial Services Commission, August 28, 2024, Three-phase KOFR adoption plan for the benchmark interest rate reform, press release. Bank of Korea, August 28, 2024, Key challenges and future directions for promoting the KOFR adoption.

2) Financial Services Commission, December 10, 2024, Benchmark interest rate reform plan for 2025, press release.

3) According to the Council, roughly 29 financial institutions fall under the category as of December 2024.

4) The “interest period” refers to the period during which interest accrues in loans or FRNs on a monthly or quarterly basis.

5) According to Bloomberg statistics, the proportion of newly issued FRNs using currency-specific RFRs as reference rates in the first half of 2024 (based on issuance value) is 96% for USD (SOFR), 100% for GBP (SONIA), 97% for CHF (SARON), 100% for JPY (TONA), 5% for EUR (€STR). In the Eurozone, EURIBOR is still widely used as the reference rate for FRNs, but the proportion of €STR is increasing.

6) Consider an FRN that references the 3-month LIBOR and pays interest every 3 months. The interest rate for this FRN is fixed as the LIBOR recorded on the first day of the interest period. As a result, once the interest rate is fixed, any fluctuations in market interest rates (3-month LIBOR) cannot be reflected until the next interest reset date. In this case, the duration of this FRN is 3 months.

7) Baklanova & Tanega, 2014, Money Market Funds in the EU and the US, Oxford University Press.

8) Klinger, S., Syrstad, O., 2024, The SOFR Discount, Working Paper, BI Norwegian Business School and Norges Bank.

9) Cooperman, H.R., Duffie, D., Luck, S., Wang, Z.Z., Yang, Y., 2024, Bank funding risk, reference rates, and credit supply, Forthcoming in Journal of Finance.

10) FSB, 2020, Reforming major interest rate benchmarks: 2020 Progress report - “The year of transition away from LIBOR.”

11) Baek, I.S. & Jang, G.H., 2024, Global benchmark interest rate regime in the post-LIBOR era and its implications for Korea, presentation materials at the “Key challenges and future directions for promoting KOFR” policy conference hosted by the Bank of Korea and Korea Capital Market Institute.

12) BIS, 2013, Towards better reference rate practices: a central bank perspective.

Financial transactions referencing benchmark rates can be broadly categorized into interest rate derivatives and cash transactions. In line with global practices, consensus has been reached in Korea to replace the reference rate for interest rate derivatives with KOFR. However, efforts to promote KOFR adoption in cash products—such as Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) and loans—remain limited. These products play a crucial role in the funding activities of various economic participants, underscoring their importance. This study briefly examines the Council’s roadmap for KOFR activation and highlights the need to foster the development of KOFR-linked bond and loan markets.

Key elements of the roadmap for promoting KOFR adoption

The Council has developed a timeline to implement KOFR in derivatives and bond markets starting in 2025. The roadmap focuses on gradually mandating KOFR-linked swaps, which are a key component of the interest rate derivatives market. Starting in July 2025, financial institutions with a nominal CD swap trading volume exceeding KRW 25 trillion over the previous 12 months will be required to execute a certain percentage of their new interest rate swap transactions as KOFR swaps.3) The recommended ratio will start at 10% in 2025 and increase by 10 percentage points each year, aiming to expand the share of KOFR swaps to over 50% of the total interest rate swaps market by 2030. Additionally, to support the smooth adoption of KOFR by financial institutions, the Korea Exchange plans to introduce central clearing for KOFR swap transactions starting in October 2025.

The transition from Inter-Bank Offered Rates (IBORs)—such as LIBOR and Korea's CD rates—to RFRs represents a cornerstone of global benchmark rate reforms. Within this context, the Council’s roadmap is significant as it aligns Korea’s reform efforts with global standards. The interest rate derivatives market is strongly influenced by liquidity externalities associated with benchmark rates, making it challenging for individual financial institutions to adopt new benchmark rates. Recognizing this aspect, major economies have introduced the “RFR First Initiative” to facilitate the adoption of RFRs in derivatives transactions. The introduction of mandatory KOFR-linked swaps under the Council’s roadmap mirrors these global initiatives. KOFR-linked swaps provide an effective mechanism for managing interest rate risks in a variety of KOFR-referenced financial transactions. As such, they are expected to play a pivotal role in the KOFR-centered benchmark rate ecosystem in Korea.

The Council also aims to expand the issuance of KOFR-linked Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) through public financial institutions, including the Korea Development Bank (KDB), the Industrial Bank of Korea (IBK), and the Export-Import Bank of Korea, as well as commercial banks. In 2024, public financial institutions in Korea issued KOFR-linked FRNs totaling KRW 800 billion. Beginning in 2025, the Council mandates that public financial institutions and commercial banks allocate at least 10% of their annual FRN issuance to KOFR-linked bonds, with a plan to gradually increase this proportion in subsequent years. This strategy parallels approaches adopted in major economies, where public financial institutions initially established RFR-linked FRN markets, enabling commercial banks to expand the market base and paving the way for non-bank financial institutions and corporations to participate in RFR-linked FRN issuance.

However, there are divergent opinions among market participants regarding the necessity of KOFR-linked FRNs in Korea. Furthermore, while the Council is expected to address the application of KOFR to loans in the future, a concrete plan for its implementation has yet to be developed. The following sections examine the economic characteristics of KOFR and its application to financial transactions in comparison with CD rates, and discuss the features of KOFR-linked FRNs and loans.

RFR (KOFR) vs. IBOR (CD rate)

RFRs and IBORs have distinct characteristics in various aspects. The primary distinction between them lies in their underlying economic substance. RFRs represent risk-free interest rates, while IBORs measure the average unsecured funding costs for banks. The inclusion of the funding cost risks of banks has been a key driver in creating the IBOR-centered ecosystem. By using IBORs as reference rates for loans, banks can transfer the risk of rising funding costs to borrowers. However, this also suggests that if banks’ credit risk increases, borrowers face higher borrowing costs, underscoring the need to hedge this risk through interest rate swaps and other instruments.

Second, RFRs and IBORs exhibit fundamental differences in their relationship with economic cycles. The RFR reflects the risk-free market rates and thus tends to behave pro-cyclically, while the IBOR is counter-cyclical because it incorporates banks' credit risks. This results in a weaker correlation between IBORs and monetary policy changes, compared to RFRs. In particular, in economic downturns or financial crises, central banks may lower policy rates to reduce market interest rates. However, the excessive reliance on IBORs in the economy and financial markets could undermine these efforts, pushing up the funding costs for economic agents.

Third, these benchmark rates differ in their interest rate determination mechanisms. IBORs, as forward-looking term rates, enable interest payments to be calculated in advance for loans and bonds. In contrast, RFRs are backward-looking overnight rates, making it impossible to determine interest payments in advance. The application of RFRs to financial transactions is categorized into two primary methods based on the timing of interest determination: the set in-arrears method and the set in-advance method. Under the set in-arrears approach, the interest rate is calculated near the end of the interest period.4) It is based on the simple or compounded average of daily RFRs over the interest period. Major economies, such as the US and the UK, predominantly use this approach for RFR-linked FRNs. On the other hand, the set in-advance approach applies an averaged RFR from a prior period to the current interest period. For instance, if an interest payment is due 3 months from now, the set in-advance method would apply the average RFR from the previous 3 months. While this approach does not reflect actual interest rate fluctuations during the interest period, it offers the advantage of allowing borrowers to know their payment amounts in advance. Major economies employ both approaches for RFR-linked loans, depending on the specific transaction or market preferences.

Characteristics of RFR FRNs

Initially, FRNs using RFRs as reference rates, unlike LIBOR-linked FRNs, were expected to pose challenges to financial markets due to the delayed determination of interest rates. However, in major economies such as the US and the UK, RFRs have rapidly been adopted as the standard reference rate for FRNs, driven by market forces.5) This swift adoption can be attributed to the following advantages that RFR-linked FRNs, utilizing the set in-arrears approach, provide to both issuers and investors compared to IBOR-linked FRNs.

First, for investors, a key advantage of RFR-linked FRNs is that bond prices exhibit significantly low sensitivity to changes in the RFR, also referred to as duration risk. The duration of an FRN is determined by the interval between interest rate resets. For example, an FRN referencing a 3-month IBOR has a duration of 3 months.6) In contrast, RFR-linked FRNs using the set in-arrears approach fully incorporate daily changes of the RFR into the interest rate determination. This results in the price of the FRN unaffected by the RFR fluctuations. This low duration risk offers significant benefits for money market funds (MMFs), which are key investors in the FRN market. In the US, Europe, and Korea, MMFs are subject to regulatory limits on the total interest rate risk of portfolio holdings, such as the weighted average maturity (WAM) or duration. In calculating the WAM for FRNs, the interest rate reset period can be used as the maturity.7) Therefore, RFR-linked FRNs with a one-day interest rate reset period under the set in-arrears method are highly beneficial for MMFs in complying with WAM regulatory requirements.

Second, recent studies indicate that when the same company issues FRNs referencing SOFR, the U.S. dollar RFR, the financing rate is significantly lower compared to LIBOR-linked FRNs.8) This phenomenon, referred to as the “SOFR discount,” is attributed to the premium formed by the higher price stability offered by SOFR-linked FRNs.

In summary, while RFR-linked FRNs using the set in-arrears approach involve the inconvenience of delayed interest determination, they offer compensatory benefits such as higher price stability and regulatory advantages for MMFs. These characteristics contribute to lower financing costs for FRN issuers. Notably, companies that issue FRNs typically operate dedicated treasury departments, enabling them to manage cash flows effectively even without predetermined interest rates. Given these factors, RFR-linked FRNs are considered to provide economic benefits to both issuers and investors compared to IBOR-linked FRNs.

Characteristics of RFR loans

The application of benchmark rates to loans varies across jurisdictions depending on various factors such as the continuity of IBORs, legal frameworks (particularly those related to consumer protection and fair trade), and borrower preferences. In Japan and the Eurozone, IBORs—TIBOR in Japan and EURIBOR in the Eurozone—remain in use and continue to serve as the primary reference rates for loans. In contrast, the discontinuation of LIBOR in the US, the UK, and Switzerland has resulted in the wide use of RFRs as benchmark rates for loans.

Compared to other financial transactions, the application of RFRs to loans has faced greater challenges during the benchmark rate reform processes in major economies. When loans are referenced to RFRs, banks are required to manage on their own the basis risk—the mismatch between asset and liability reference rates—or the funding cost risks that were previously transferred to borrowers. For this reason, some banks and academics have raised concerns that in economies where loan reference rates, such as RFRs, do not reflect banks' funding costs, credit creation by banks could decline, and borrowing costs for economic agents might increase compared to scenarios where IBOR-linked loans remain available.9) However, evidence from the US, the UK, and Switzerland suggests that retail borrowers tend to prefer RFR-linked loans. Additionally, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and other financial authorities have evaluated the pro-cyclical nature of RFRs as a potential contributor to consumer protection in financial markets. Central banks have also expressed the view that RFR-linked loans are more suitable than IBOR-linked loans for enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy.10)

Therefore, it is important to monitor the macroeconomic effects of RFR-linked loans in the US, the UK, and Switzerland. However, regardless of whether IBORs remain in use, it is worth noting that major economies, particularly for retail loans, often use reference rates that do not include banks' credit risks, such as RFRs, central bank policy rates, and government bond yields.11)

Current state and implications in Korea

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of reference rates used in the domestic FRN market. In Korea, a variety of institutions—including banks, non-bank financial institutions, and corporations—issue FRNs. The primary reference rates used in the market include 1-month and 3-month CD rates, CD swap rates, and CP rates. Notably, banks, which are the largest issuers of FRNs in the domestic market, often use the 1-month CD rate as the reference rate instead of the 3-month CD rate. This preference appears to be driven by MMFs, the key investors in FRNs, which favor shorter-term CD rates to comply with WAM regulations.

However, unlike major economies, Korea has yet to designate the maturity of KOFR-linked FRNs as one day under WAM regulations. Moving forward, regulatory adjustments should be made to create an environment where the economic advantages of KOFR-linked FRNs can be fully realized, enabling various FRN issuers, including banks, to benefit from the “KOFR discount.”

As shown in Table 2, the primary reference rates for loans used by banks in Korea all incorporate their funding costs. This structure, which is rarely observed in major economies, systematically transfers the risk of banks’ funding costs to retail borrowers, leading to the following implications.

First, the current system enables banks to avoid bearing basis risk arising from their loan transactions. This structure effectively facilitates lending activities. Second, from a financial stability perspective, IBOR-linked loans—such as those referencing CD rates—are beneficial only if borrowers can effectively manage the borrowing rate risks transferred from banks.12) While large corporations are generally equipped to manage such risks using instruments like CD swaps, households and SMEs typically lack the financial tools and expertise to do so. Therefore, the current lending regime, which transfers banks’ funding cost risks to households and SMEs, warrants careful reassessment. Third, in this environment, the price of loans should be determined to ensure transparency and efficiency. As shown in Table 2, however, the diversity of loan reference rates in Korea makes it complicated for retail borrowers to compare and evaluate the price of loans across banks.

1) Financial Services Commission, August 28, 2024, Three-phase KOFR adoption plan for the benchmark interest rate reform, press release. Bank of Korea, August 28, 2024, Key challenges and future directions for promoting the KOFR adoption.

2) Financial Services Commission, December 10, 2024, Benchmark interest rate reform plan for 2025, press release.

3) According to the Council, roughly 29 financial institutions fall under the category as of December 2024.

4) The “interest period” refers to the period during which interest accrues in loans or FRNs on a monthly or quarterly basis.

5) According to Bloomberg statistics, the proportion of newly issued FRNs using currency-specific RFRs as reference rates in the first half of 2024 (based on issuance value) is 96% for USD (SOFR), 100% for GBP (SONIA), 97% for CHF (SARON), 100% for JPY (TONA), 5% for EUR (€STR). In the Eurozone, EURIBOR is still widely used as the reference rate for FRNs, but the proportion of €STR is increasing.

6) Consider an FRN that references the 3-month LIBOR and pays interest every 3 months. The interest rate for this FRN is fixed as the LIBOR recorded on the first day of the interest period. As a result, once the interest rate is fixed, any fluctuations in market interest rates (3-month LIBOR) cannot be reflected until the next interest reset date. In this case, the duration of this FRN is 3 months.

7) Baklanova & Tanega, 2014, Money Market Funds in the EU and the US, Oxford University Press.

8) Klinger, S., Syrstad, O., 2024, The SOFR Discount, Working Paper, BI Norwegian Business School and Norges Bank.

9) Cooperman, H.R., Duffie, D., Luck, S., Wang, Z.Z., Yang, Y., 2024, Bank funding risk, reference rates, and credit supply, Forthcoming in Journal of Finance.

10) FSB, 2020, Reforming major interest rate benchmarks: 2020 Progress report - “The year of transition away from LIBOR.”

11) Baek, I.S. & Jang, G.H., 2024, Global benchmark interest rate regime in the post-LIBOR era and its implications for Korea, presentation materials at the “Key challenges and future directions for promoting KOFR” policy conference hosted by the Bank of Korea and Korea Capital Market Institute.

12) BIS, 2013, Towards better reference rate practices: a central bank perspective.