Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

Retail Investors during Covid-19 Pandemic

Publication date Mar. 09, 2021

Summary

After the outbreak of Covid-19, retail trading in Korea hit an all-time high, with the net buying and trading value soaring to unprecedented levels. The incredibly active trading of retail investors for the past year is estimated to add an extra KRW 13 trillion profit to the gains from their holdings purchased prior to the pandemic. However, the extra profit appears to underperform the market, and the sudden increase in trading value only pushed up the transaction costs such as transaction taxes and brokerage fees to KRW 13.7 trillion. It appears that high volatility and abrupt rebounds in stock prices during the pandemic era bolster retail investors’ over-confidence about their investment capability while fueling their expectations for extremely high returns, which altogether triggered those investors to trade excessively. Retail investors’ lack of investment capability and behavioral biases likely undermine their direct investment performance. A desirable approach is to encourage those investors to tap into more indirect investment vehicles and professional investment advice.

It has been over one year since Covid-19 began spreading in Korea. Despite the drastic shock from the global declaration of the pandemic, Korea’s stock market quickly rebounded on the back of its superb quarantine performance, abundant liquidity, and solid earnings of listed companies. The KOSPI once dipped to around 1,400 points in late March, but quickly turned around to reach the pre-Covid-19 level of 2,200 in July 2020. At the beginning of this year, it even surpassed the 3,000 mark. Since then, the pace of the upward movement slowed down slightly amid concerns about the market becoming overheated.

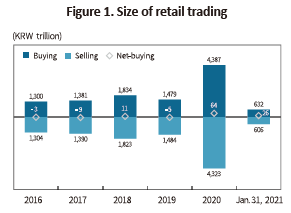

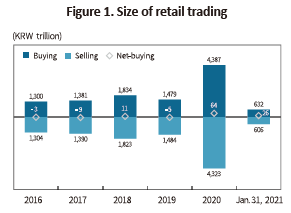

One of the most distinctive features in post-outbreak stock market is the increased presence of retail investors. Their net-buying reached KRW 63.8 trillion in 2020, and KRW 25.9 trillion in January 2021 alone, with the number of retail active accounts going up by 7.6 million from 29.36 million in early 2020 to 36.96 million in end-January 2021. Such a concentrated inflow of new investment and new investors is unprecedented. What’s more impressive is the size of their trading value. During 2020, their buying and selling reached KRW 4,387 trillion and KRW 4,323 trillion, respectively, which is a 2.9-fold increase from the 2016-2019 average, and 2.5 times the stock market capitalization of 2020.

It is not hard to assume that retail investors could have perceived the Covid-19 crisis as an investment opportunity that is hardly likely to come again in the future. The question is whether or not retail investors could have achieved investment performance they had expected from massive trading. This is what this article is trying to figure out based on an analysis on their trading performance during the Covid-19 era, with some thoughts on the implications of the results.

Performance of retail investors

This article assesses retail investors’ trading performance using trading profits out of their transactions from February 2020.1) The analysis takes into account the “extra” profits only, excluding the gains retail investors earned from their portfolio holdings as of end-January 2020. For example, assume that an investor holds 100 shares each of which is KRW 10,000 at the end of 2020, and that this investor bought another 10 shares at KRW 12,000 at June 2020. If the stock price climbed to KRW 15,000 at the end of January 2021, the investor’s trading profit would have reached KRW 30,000 (KRW 15,000 minus KRW 12,000, and the result multiplied by 10). The profit from previous holdings—KRW 500,000 (KRW 15,000 minus KRW 10,000, and the result multiplied by 10)—is not counted.

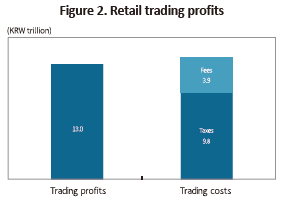

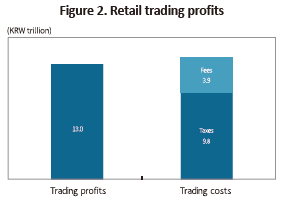

Of the common shares of KOSPI- and KOSDAQ-listed firms, this analysis selected 1,807 stocks that could be analyzed accurately.2) During twelve months between February 2020 and January 2021, retail investors’ trading profits out of those selected stocks reached approximately KRW 13 trillion. This is a significant amount given that gains from their holdings bought before the pandemic were KRW 70 trillion. However, what’s problematic is the cost of trading. Including the tax of KRW 9.8 trillion (25bp of the amount sold) and the brokerage fee of KRW 3.9 trillion (5bp of the transaction value), the overall trading cost reached KRW 13.7 trillion, which is KRW 700 billion larger than the trading profits. This suggests that retail investors bore massive trading costs that are enough to offset their extra trading profits for the past year.

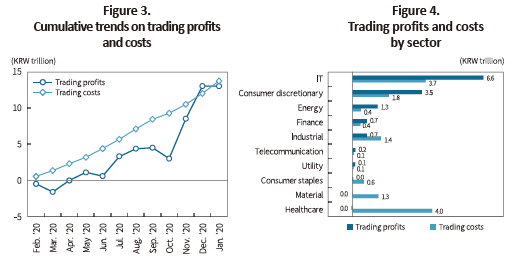

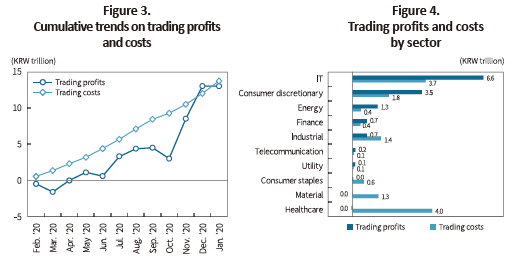

A look at cumulative monthly trading profits reveals a trend similar to the stock index. Most evidently, the trading profit was as large as KRW 10 trillion during November and December rallies. The cumulative trading cost was persistently larger than the cumulative trading profit, except for December 2020. In October—right before the trading profit increased immensely in November and December—the gap had reached KRW 6.3 trillion.

By sector, the trading profit was largest in IT, followed by consumer discretionary, energy, and finance. In the era of Covid-19, retail trading profits appear to have occurred mostly in the cyclical sector where stock prices fluctuated heavily. Particularly, the IT sector recorded a trading profit of KRW 6.6 trillion, accounting for over a half of the overall trading profit. However, the net trading profit would fall to KRW 2.9 trillion after trading costs of KRW 3.7 trillion. Although the healthcare sector barely produced any trading profit that was the lowest among all sectors analyzed, its trading cost reached KRW 4 trillion, the highest among all sectors.

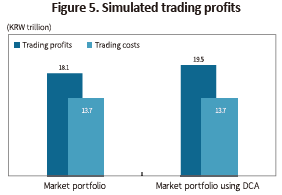

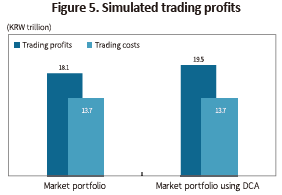

The analyses so far demonstrate that active retail trading during the Covid-19 era failed to produce extra profits. Although the cause could likely be the large size of trading costs, another possibility also exists, for example, the small size of trading profits. To test such a possibility, a simulation was carried out, assuming that a hypothetical stock tracks a hypothetical index that is a weighted average of KOSPI and KOSDAQ indexes, and that the stock is the only stock bought and sold by retail investors during trading dates. In other words, this is an assumption that retail investors track market portfolios. Under the simulation, the trading profit using the same method applied earlier reached KRW 18.1 trillion, KRW 5.1 trillion higher than the actual profit of KRW 13 trillion. Because the trading value was assumed to remain intact, the net trading profit after trading costs would be also KRW 5.1 trillion larger. Such a result implies that retail investors’ stock selection remained inefficient during the pandemic period.

Another analysis was carried out under an assumption that retail investors bought and sold an equal amount of the hypothetical stock everyday during the past year. Except for the trading cost, this is in effect a dollar cost averaging strategy where an investor net buys an equal amount of market portfolios at regular intervals. In this case, the trading profit—with the trading value unchanged—was larger than the actual profit by KRW 6.5 trillion, and the simulated profit above by KRW 1.4 trillion. What this means is that retail investors were inefficient in terms of not only stock selection, but also market timing.

Excessive retail trading

For the past year after the Covid-19 outbreak, retail investors are estimated to have earned approximately KRW 70 trillion from the price increase in the stocks held before the outbreak. However, the analyses in this article show that they failed to reap extra profits out of their massive trading after the outbreak. Then why did retail investors trade so frequently that their trading costs become sufficient to offset their extra trading profit? Indeed, retail investors in Korea had a high turnover even before the Covid-19 outbreak. Their pre-pandemic turnover was higher than that of domestic institutional investors by two to three times, and foreign investors by three to four times. Excessive trading of retail investors is a tendency that has been long observed outside Korea as well.3)

There have been two lines of explanations for excessive retail trading. First, retail investors are swayed by overconfidence.4) Believing that they are capable of investment, and that their information is accurate, retail investors often trade more frequently than necessary. Although such overconfidence is also observed among institutional investors, the tendency is more evident among retail investors. Investors participating in the highly uncertain stock market are more likely to have overconfidence. They often believe that their superb investment performance is based on their own capability, while viewing their failure as lack of luck. Hence, overconfidence may hardly disappear from the stock market. Empirical results show that overconfident investors trade more frequently, track past returns and trading volume, which leads to low performance. The tendency of overconfidence is also pointed to as a culprit behind overvaluation and a bubble.

The second explanation perceives stock investment as an opportunity for a windfall profit or gambling. Investors with that perception tend to prefer highly volatile stocks or lottery-type stocks, and to overestimate the probability of a drastic price increase. In pursuit of excitement and thrills from extremely high returns, this type of investors exhibit high levels of turnover and trade frequency. Markets such as the US, Germany, and Taiwan reported a decline in stock trading after the launch of lotteries, and a fall in retail stock trading on every lottery jackpot date, both of which evidence retail investors perceiving stocks as an alternative to lottery tickets.5) Predictably, stocks preferred by investors seeking extreme gains were found to underperform others.

Such behavioral features came to emerge among retail investors more evidently during the pandemic period. It is likely that rising volatility and abrupt price rebounds could have nurtured ripe conditions for bolstering overconfidence and fueling expectations for extremely high returns. There is also the impact of the now online-centered trading environment. A diverse range of information available online could easily mislead investors to believe that they hold sufficient investment knowledge. Also, the convenient online trading environment could delude investors into believing that they are controlling a series of investment processes. This is one of the causes that triggered excessive trading.6)

Conclusion

Retail investors represent a significant portion in Korea’s stock market. They actually are a dominant market force holding up the KOSDAQ market. However, what if their abundant liquidity is based on overconfidence or gambling behavior? If the tendency is only accumulating sluggish returns, is the current condition sustainable? Their massive demand for investment confirmed during the pandemic period on one hand assures the growth potential of Korea’s stock market. But on the other hand, this could fuel concerns about some side effects in the post-Covid-19 era. It is hard to expect retail stock investors to learn from their failure because the cost of failure is too high to afford, and also because learning how to invest requires more than failure alone. For retail investors who are exposed to behavioral biases and lacking capability, it would be wise to capitalize on professional advisory services and indirect investment tools such as mutual funds. What’s needed the most for financial firms providing those services is to earn confidence of retail investors.

1) Refer to Comerton-Forde et al. (2010) and Menkveld (2013).

2) The analysis excludes SPAC and stocks whose number of outstanding shares changed more than 10% due to corporate events other than stock splits or reverse-splits during the analysis period. A total of 1,807 stocks analyzed here account for 95% of market capitalization and 86% of the overall trading value.

3) This is called an excessive trading puzzle.

4) Barber and Odean (2000)

5) Barber et al. (2009), Gao and Lin (2015), Dorn et al. (2015)

6) Barber and Odean (2002), Choi et al. (2002)

References

Barber, B. M., Odean, T., 2000, Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. The Journal of Finance 55(2), 773-806.

Barber, B. M., Odean, T., 2002, Online investors: do the slow die first?. The Review of Financial Studies 15(2), 455-488.

Barber, B. M., Lee, Y. T., Liu, Y. J., Odean, T., 2009, Just how much do individual investors lose by trading? The Review of Financial Studies 22(2), 609-632.

Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Metrick, A., 2002, How does the internet affect trading? Evidence from investor behavior in 401 (k) plans, Journal of Financial Economics 64(3), 397-421.

Comerton-Forde, C., Hendershott, T., Jones, C. M., Moulton, P. C., Seasholes, M. S., 2010, Time variation in liquidity: The role of market-maker inventories and revenues, The Journal of Finance 65(1), 295-331.

Dorn, A. J., Dorn, D., Sengmueller, P., 2015, Trading as gambling. Management Science 61(10), 2376-2393.

Gao, X., Lin, T. C., 2015, Do individual investors treat trading as a fun and exciting gambling activity? Evidence from repeated natural experiments. The Review of Financial Studies 28(7), 2128-2166.

Menkveld, A. J., 2013, High frequency trading and the new market makers, Journal of Financial Markets 16(4), 712-740.

One of the most distinctive features in post-outbreak stock market is the increased presence of retail investors. Their net-buying reached KRW 63.8 trillion in 2020, and KRW 25.9 trillion in January 2021 alone, with the number of retail active accounts going up by 7.6 million from 29.36 million in early 2020 to 36.96 million in end-January 2021. Such a concentrated inflow of new investment and new investors is unprecedented. What’s more impressive is the size of their trading value. During 2020, their buying and selling reached KRW 4,387 trillion and KRW 4,323 trillion, respectively, which is a 2.9-fold increase from the 2016-2019 average, and 2.5 times the stock market capitalization of 2020.

Performance of retail investors

This article assesses retail investors’ trading performance using trading profits out of their transactions from February 2020.1) The analysis takes into account the “extra” profits only, excluding the gains retail investors earned from their portfolio holdings as of end-January 2020. For example, assume that an investor holds 100 shares each of which is KRW 10,000 at the end of 2020, and that this investor bought another 10 shares at KRW 12,000 at June 2020. If the stock price climbed to KRW 15,000 at the end of January 2021, the investor’s trading profit would have reached KRW 30,000 (KRW 15,000 minus KRW 12,000, and the result multiplied by 10). The profit from previous holdings—KRW 500,000 (KRW 15,000 minus KRW 10,000, and the result multiplied by 10)—is not counted.

Of the common shares of KOSPI- and KOSDAQ-listed firms, this analysis selected 1,807 stocks that could be analyzed accurately.2) During twelve months between February 2020 and January 2021, retail investors’ trading profits out of those selected stocks reached approximately KRW 13 trillion. This is a significant amount given that gains from their holdings bought before the pandemic were KRW 70 trillion. However, what’s problematic is the cost of trading. Including the tax of KRW 9.8 trillion (25bp of the amount sold) and the brokerage fee of KRW 3.9 trillion (5bp of the transaction value), the overall trading cost reached KRW 13.7 trillion, which is KRW 700 billion larger than the trading profits. This suggests that retail investors bore massive trading costs that are enough to offset their extra trading profits for the past year.

By sector, the trading profit was largest in IT, followed by consumer discretionary, energy, and finance. In the era of Covid-19, retail trading profits appear to have occurred mostly in the cyclical sector where stock prices fluctuated heavily. Particularly, the IT sector recorded a trading profit of KRW 6.6 trillion, accounting for over a half of the overall trading profit. However, the net trading profit would fall to KRW 2.9 trillion after trading costs of KRW 3.7 trillion. Although the healthcare sector barely produced any trading profit that was the lowest among all sectors analyzed, its trading cost reached KRW 4 trillion, the highest among all sectors.

Another analysis was carried out under an assumption that retail investors bought and sold an equal amount of the hypothetical stock everyday during the past year. Except for the trading cost, this is in effect a dollar cost averaging strategy where an investor net buys an equal amount of market portfolios at regular intervals. In this case, the trading profit—with the trading value unchanged—was larger than the actual profit by KRW 6.5 trillion, and the simulated profit above by KRW 1.4 trillion. What this means is that retail investors were inefficient in terms of not only stock selection, but also market timing.

For the past year after the Covid-19 outbreak, retail investors are estimated to have earned approximately KRW 70 trillion from the price increase in the stocks held before the outbreak. However, the analyses in this article show that they failed to reap extra profits out of their massive trading after the outbreak. Then why did retail investors trade so frequently that their trading costs become sufficient to offset their extra trading profit? Indeed, retail investors in Korea had a high turnover even before the Covid-19 outbreak. Their pre-pandemic turnover was higher than that of domestic institutional investors by two to three times, and foreign investors by three to four times. Excessive trading of retail investors is a tendency that has been long observed outside Korea as well.3)

There have been two lines of explanations for excessive retail trading. First, retail investors are swayed by overconfidence.4) Believing that they are capable of investment, and that their information is accurate, retail investors often trade more frequently than necessary. Although such overconfidence is also observed among institutional investors, the tendency is more evident among retail investors. Investors participating in the highly uncertain stock market are more likely to have overconfidence. They often believe that their superb investment performance is based on their own capability, while viewing their failure as lack of luck. Hence, overconfidence may hardly disappear from the stock market. Empirical results show that overconfident investors trade more frequently, track past returns and trading volume, which leads to low performance. The tendency of overconfidence is also pointed to as a culprit behind overvaluation and a bubble.

The second explanation perceives stock investment as an opportunity for a windfall profit or gambling. Investors with that perception tend to prefer highly volatile stocks or lottery-type stocks, and to overestimate the probability of a drastic price increase. In pursuit of excitement and thrills from extremely high returns, this type of investors exhibit high levels of turnover and trade frequency. Markets such as the US, Germany, and Taiwan reported a decline in stock trading after the launch of lotteries, and a fall in retail stock trading on every lottery jackpot date, both of which evidence retail investors perceiving stocks as an alternative to lottery tickets.5) Predictably, stocks preferred by investors seeking extreme gains were found to underperform others.

Such behavioral features came to emerge among retail investors more evidently during the pandemic period. It is likely that rising volatility and abrupt price rebounds could have nurtured ripe conditions for bolstering overconfidence and fueling expectations for extremely high returns. There is also the impact of the now online-centered trading environment. A diverse range of information available online could easily mislead investors to believe that they hold sufficient investment knowledge. Also, the convenient online trading environment could delude investors into believing that they are controlling a series of investment processes. This is one of the causes that triggered excessive trading.6)

Conclusion

Retail investors represent a significant portion in Korea’s stock market. They actually are a dominant market force holding up the KOSDAQ market. However, what if their abundant liquidity is based on overconfidence or gambling behavior? If the tendency is only accumulating sluggish returns, is the current condition sustainable? Their massive demand for investment confirmed during the pandemic period on one hand assures the growth potential of Korea’s stock market. But on the other hand, this could fuel concerns about some side effects in the post-Covid-19 era. It is hard to expect retail stock investors to learn from their failure because the cost of failure is too high to afford, and also because learning how to invest requires more than failure alone. For retail investors who are exposed to behavioral biases and lacking capability, it would be wise to capitalize on professional advisory services and indirect investment tools such as mutual funds. What’s needed the most for financial firms providing those services is to earn confidence of retail investors.

1) Refer to Comerton-Forde et al. (2010) and Menkveld (2013).

2) The analysis excludes SPAC and stocks whose number of outstanding shares changed more than 10% due to corporate events other than stock splits or reverse-splits during the analysis period. A total of 1,807 stocks analyzed here account for 95% of market capitalization and 86% of the overall trading value.

3) This is called an excessive trading puzzle.

4) Barber and Odean (2000)

5) Barber et al. (2009), Gao and Lin (2015), Dorn et al. (2015)

6) Barber and Odean (2002), Choi et al. (2002)

References

Barber, B. M., Odean, T., 2000, Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. The Journal of Finance 55(2), 773-806.

Barber, B. M., Odean, T., 2002, Online investors: do the slow die first?. The Review of Financial Studies 15(2), 455-488.

Barber, B. M., Lee, Y. T., Liu, Y. J., Odean, T., 2009, Just how much do individual investors lose by trading? The Review of Financial Studies 22(2), 609-632.

Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Metrick, A., 2002, How does the internet affect trading? Evidence from investor behavior in 401 (k) plans, Journal of Financial Economics 64(3), 397-421.

Comerton-Forde, C., Hendershott, T., Jones, C. M., Moulton, P. C., Seasholes, M. S., 2010, Time variation in liquidity: The role of market-maker inventories and revenues, The Journal of Finance 65(1), 295-331.

Dorn, A. J., Dorn, D., Sengmueller, P., 2015, Trading as gambling. Management Science 61(10), 2376-2393.

Gao, X., Lin, T. C., 2015, Do individual investors treat trading as a fun and exciting gambling activity? Evidence from repeated natural experiments. The Review of Financial Studies 28(7), 2128-2166.

Menkveld, A. J., 2013, High frequency trading and the new market makers, Journal of Financial Markets 16(4), 712-740.