Our bi-weekly Opinion provides you with latest updates and analysis on major capital market and financial investment industry issues.

The Role of Transition Finance in Achieving Carbon Neutrality

Publication date May. 02, 2023

Summary

The Korean government plans to spend around KRW 89.9 trillion between 2023 and 2027 to implement the transition to carbon neutrality. The existing green finance framework is expected to play a role in intermediating and executing the funds for the transition. But the framework seems insufficient to achieve carbon neutrality in terms of incentives and effectiveness because high carbon-emitting industries taking up most of carbon emissions are not eligible for green finance. The G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group points out the fact that greenhouse gas-intensive sectors have limited access to financing for the transition to decarbonization and proposes a transition finance framework to ensure that high-emitting industries take an orderly shift toward carbon mitigation. To this end, sustainability-linked bonds or loans are expected to serve as a critical tool. On the other hand, shareholders are likely to benefit more from shareholder engagement aimed at inducing an orderly, long-term shift toward carbon neutrality than from a divestment strategy for high-emitting industries. On top of that, disclosure for preventing carbon lock-in should be arranged in parallel with a verification system.

Pathways to decarbonization

In 2021, Korea brought into force the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth for Coping with Climate Crisis (the “Framework Act on Carbo Neutrality”) to support the transition to carbon neutrality. Under the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality, Korea determined the medium- and long-term target to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% by 2030, compared to the 2018 level. To deliver the target, the Korean government announced a detailed plan on March 21,1) including mitigation targets by year and sector, specific challenges and sector-specific GHG emissions reduction policy.

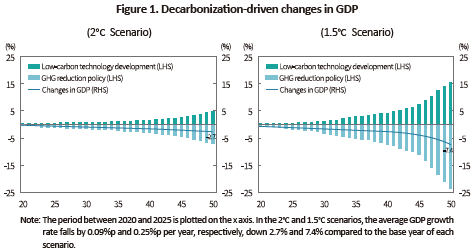

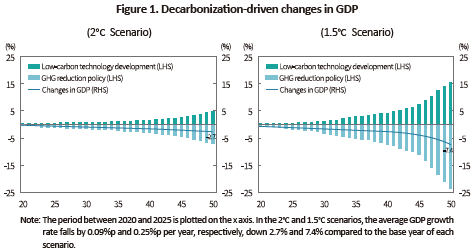

It is widely agreed that the year 2030 is a tight deadline, in light of the intensity and feasibility of mitigation targets. The implementation of a carbon neutrality policy will drive up the cost of GHG emissions across the economy, contributing to raising corporate production costs and lowering added value. Understandably, there are concerns about the policy’s adverse impact. On the other hand, new technologies and industries that enable the transition to decarbonization are expected to alleviate such concerns. Bank of Korea conducted a survey on the medium- and long-term change in GDP driven by decarbonization policy, as illustrated in Figure 1.2) Building upon mutual compensation effects from GHG reduction policy and the development of low-carbon technologies, the net change in GDP stands at -2.7% for the 2℃ scenario and -7.4% for the more aggressive 1.5℃ scenario.3)

The major factor behind decarbonization-driven GDP changes is a drop in added value of companies that belong to high carbon-emitting industries. These companies are most influenced by decarbonization policy because it is difficult to secure a stable and efficient supply of renewable energy that can replace carbon energy sources.

Business types of the companies are categorized into primary metals (steel, metal casting), electricity supply (coal-fired power generation), nonferrous metal and mineral products (cement), chemicals and chemical products (petrochemicals and compounds), and coke·briquettes·refined petroleum products (oil refining). Such business types fall under the conversion sector4) and industrial sector set forth by the first National Plan for Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth. As of 2018, carbon emissions from the two sectors account for 37% and 36% of Korea’s total GHG emissions of 727.6 million CO2eq, respectively. This suggests the key to achieving carbon neutrality lies in carbon mitigation activities of high carbon-emitting industries.

Large-scale financing

The transition to carbon neutrality requires a huge amount of funds for the next 30 years. McKinsey & Company estimates the annual investment needed for the transition to be worth $9.2 trillion (around KRW 12,000 trillion) between 2021 and 2050 globally.5) Considering the period for developing and putting into practice relevant technologies, funding should be preemptively concentrated on the next decade. In Europe, the investment in energy and transportation infrastructure necessary for carbon neutrality is estimated at €340 billion (around KRW 490 trillion) for the next 15 years between 2021 and 2035.6)

In the GX League Basic Concept (plan) announced by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in December 2022, Japan specifies that an annual investment of JPY 17 trillion (around KRW 169 trillion) is required for its Green Transformation (GX) for the next decade. The Japanese government initially plans to issue transition bonds worth JPY 20 trillion to encourage private investment and execute preemptive investments. The redemption of transition bonds will be covered by revenues generated from the long-term carbon tax imposition and paid allocation of GHG emissions that is carried out in parallel with carbon pricing normalization.

According to its first National Plan for Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth, Korea intends to inject about KRW 89.9 trillion into the transition for the next five years between 2023 and 2027. To be specific, a total of KRW 54.6 trillion will be spent on GHG emissions reduction projects including core technology development for carbon-neutral industries (industrial sector), zero energy·green remodeling (building sector) and electric vehicle·hydrogen vehicle grants (transportation sector), while KRW 19.4 trillion and KRW 6.5 trillion will be put into climate adaptation and green industry growth, respectively.

Financing plans developed by global economies ultimately aim at achieving carbon neutrality. However, it is noteworthy that the existing green finance falling within the sustainable finance category and green taxonomy fall short of delivering carbon neutrality in terms of incentives and effectiveness.

Need for transition finance framework

Finance designed for improving the environment and fighting against climate change is generally referred to as green finance. Green taxonomy, a classification system of environmentally sustainable economic activities, has been established to facilitate green finance and avoid greenwashing. Notably, carbon-intensive sectors taking up most of carbon emissions are not eligible for green finance. This means achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 would be a practical impossibility unless transition activities are undertaken by high carbon-emitting sectors.

The OECD defines transition finance as finance raised or deployed by companies to implement their net-zero transition, which aligns with the Paris Agreement, under credible corporate climate transition plans.7) In Japan’s GX League Basic Concept (plan), transition finance is understood as finance supporting the long-term net-zero transition to attain carbon neutrality in the corporate sector. In the 2022 G20 Sustainable Finance Report,8) the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group points out that sustainable finance has focused only on pure green activities and GHG-intensive sectors have limited access to transition finance and proposes a transition finance framework to enable high-emitting industries to take an orderly shift toward carbon mitigation.

The relevant framework is needed to make sure that a taxonomy classification, disclosure and verification are conducted objectively and transparently. Taxonomy should play a role in avoiding transition-washing9) by ensuring that economic and investment activities that facilitate the carbon neutrality transition are recognized. Companies should conduct the objective and transparent disclosure of their plans to meet net-zero targets set forth by the Paris Agreement and scientifically substantiate and verify the feasibility of the plans.

Features of financial intermediation designed for carbon neutrality

The transition to carbon neutrality is affected by long-term policies that reflect socio-economic preferences of stakeholders. As the development of transformative technologies, an enabler of the transition, is the product of scientific advancement, the transition process involves uncertainty. Accordingly, transition finance should take account of these characteristics.

Financial instruments aimed at supporting transition activities can be largely divided into ordinary bonds, sustainability-linked bonds and sustainability-linked loans.10) How such instruments meet the purpose of fund execution and align with an incentive mechanism related to carbon reduction verification can be enforced by a contract. For instance, if a power plant using carbon fuels issues sustainability-linked bonds to raise funds for carbon capture technologies, the bond yield could be linked to the effectiveness of such technologies. As the issuance yield is an effective tool to induce a shift in companies’ activities in that it affects the cost of capital. Furthermore, sustainability-linked loans offered in the form of relationship-based banking can be characterized by transition finance as they can encourage companies to move toward a low-carbon business structure by providing customized products and services.

On the other hand, shareholders have primarily adopted negative screening by excluding high-emitting businesses from investment portfolios. But this divestment strategy has been known for marginally affecting the change in corporate activities and effective carbon mitigation. If the price elasticity of demand is high, business types that are excluded from portfolios due to high carbon intensity would end up being integrated into other portfolios without considerable price changes and rarely have significant effects on the cost of capital.11) Substitute investors would show indistinctive preference to climate change and thus, incentives for corporate carbon neutrality become no longer valid. In the 2014 policy report,12) Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, states that shareholders should undertake a long-term engagement strategy designed to induce companies using or producing fossil fuels to systematically transition to decarbonization, which fulfills the purpose of increasing shareholder value. Korea’s National Pension Service also needs to consider adopting shareholder engagement to deal with climate issues based on the principles for responsible investment and guidelines on fiduciary duty.

Implications

Korea’s carbon neutrality policy is underpinned by the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality. Article 58 of the Act (Financial Support and Revitalization) highlights the need for raising carbon neutrality funds, developing financial instruments, revitalizing private investment, stepping up disclosure of information regarding carbon neutrality, and facilitating transactions in the carbon market. Korea has founded the Presidential Commission on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth to establish and implement major policies and plans for carbon neutrality and green growth. To mobilize massive funds for the low carbon transition and effectively intermediate fund execution, the commission should handle finance as a critical part of the transition equation.

1) The first National Plan for Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth (government proposal) to achieve carbon neutrality and green growth by 2050

2) Kim, J.Y. & Jeon, E.K., 2021, Climate Change Transition Risks and Financial Stability, Bank of Korea Monthly Statistical Bulletin, Vol.75 No.12.

3) The analysis of Bank of Korea’s scenarios stems from climate change scenarios of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), under the assumption that execution and physical risks are minimized through an orderly transition.

4) The conversion sector refers to a sector consisting of electric power and calorie generation where fuel sources such as coal and gas are converted into electricity and thermal energy.

5) McKinsey & Company and Institute of International Finance, 2023, Financing the Net-Zero Transition: From Planning to Practice.

6) Klaaßen, L., Steffen, B., 2023, Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe, Nature Climate Change 13(1), 1-9.

7) OECD, 2022, OECD Guidance on Transition Finance: Ensuring Credibility of Corporate Climate Transition Plan.

8) G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, 2022, 2022 G20 Sustainable Finance Report.

9) If new investments made by high-emitting industries focus more on making the existing carbon-intensive process efficient than cutting carbon emissions, this could lead to negative consequences in the long run, such as GHG intensive lock-in.

10) Tandon, A., 2021, Transition finance: Investigating the state of play: A stocktake of emerging approaches and financial instruments, OECD Environment Working Papers No.179.

11) Berk J. B., van Binsbergen, J. H., 2021, The impact of impact investing, Research Papers 2981, Stanford University, Graduate School of Business.

12) Skancke, M., Dimson, E., Hoel, M., Kettis, M., Nystuen, G., Starks, L., 2014, Fossil-fuel investments in the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global: Addressing climate issues through exclusion and active ownership, A report by the Expert Group appointed by the Norwegian Ministry of Finance.

In 2021, Korea brought into force the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth for Coping with Climate Crisis (the “Framework Act on Carbo Neutrality”) to support the transition to carbon neutrality. Under the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality, Korea determined the medium- and long-term target to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% by 2030, compared to the 2018 level. To deliver the target, the Korean government announced a detailed plan on March 21,1) including mitigation targets by year and sector, specific challenges and sector-specific GHG emissions reduction policy.

It is widely agreed that the year 2030 is a tight deadline, in light of the intensity and feasibility of mitigation targets. The implementation of a carbon neutrality policy will drive up the cost of GHG emissions across the economy, contributing to raising corporate production costs and lowering added value. Understandably, there are concerns about the policy’s adverse impact. On the other hand, new technologies and industries that enable the transition to decarbonization are expected to alleviate such concerns. Bank of Korea conducted a survey on the medium- and long-term change in GDP driven by decarbonization policy, as illustrated in Figure 1.2) Building upon mutual compensation effects from GHG reduction policy and the development of low-carbon technologies, the net change in GDP stands at -2.7% for the 2℃ scenario and -7.4% for the more aggressive 1.5℃ scenario.3)

The major factor behind decarbonization-driven GDP changes is a drop in added value of companies that belong to high carbon-emitting industries. These companies are most influenced by decarbonization policy because it is difficult to secure a stable and efficient supply of renewable energy that can replace carbon energy sources.

Large-scale financing

The transition to carbon neutrality requires a huge amount of funds for the next 30 years. McKinsey & Company estimates the annual investment needed for the transition to be worth $9.2 trillion (around KRW 12,000 trillion) between 2021 and 2050 globally.5) Considering the period for developing and putting into practice relevant technologies, funding should be preemptively concentrated on the next decade. In Europe, the investment in energy and transportation infrastructure necessary for carbon neutrality is estimated at €340 billion (around KRW 490 trillion) for the next 15 years between 2021 and 2035.6)

In the GX League Basic Concept (plan) announced by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in December 2022, Japan specifies that an annual investment of JPY 17 trillion (around KRW 169 trillion) is required for its Green Transformation (GX) for the next decade. The Japanese government initially plans to issue transition bonds worth JPY 20 trillion to encourage private investment and execute preemptive investments. The redemption of transition bonds will be covered by revenues generated from the long-term carbon tax imposition and paid allocation of GHG emissions that is carried out in parallel with carbon pricing normalization.

According to its first National Plan for Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth, Korea intends to inject about KRW 89.9 trillion into the transition for the next five years between 2023 and 2027. To be specific, a total of KRW 54.6 trillion will be spent on GHG emissions reduction projects including core technology development for carbon-neutral industries (industrial sector), zero energy·green remodeling (building sector) and electric vehicle·hydrogen vehicle grants (transportation sector), while KRW 19.4 trillion and KRW 6.5 trillion will be put into climate adaptation and green industry growth, respectively.

Financing plans developed by global economies ultimately aim at achieving carbon neutrality. However, it is noteworthy that the existing green finance falling within the sustainable finance category and green taxonomy fall short of delivering carbon neutrality in terms of incentives and effectiveness.

Need for transition finance framework

Finance designed for improving the environment and fighting against climate change is generally referred to as green finance. Green taxonomy, a classification system of environmentally sustainable economic activities, has been established to facilitate green finance and avoid greenwashing. Notably, carbon-intensive sectors taking up most of carbon emissions are not eligible for green finance. This means achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 would be a practical impossibility unless transition activities are undertaken by high carbon-emitting sectors.

The OECD defines transition finance as finance raised or deployed by companies to implement their net-zero transition, which aligns with the Paris Agreement, under credible corporate climate transition plans.7) In Japan’s GX League Basic Concept (plan), transition finance is understood as finance supporting the long-term net-zero transition to attain carbon neutrality in the corporate sector. In the 2022 G20 Sustainable Finance Report,8) the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group points out that sustainable finance has focused only on pure green activities and GHG-intensive sectors have limited access to transition finance and proposes a transition finance framework to enable high-emitting industries to take an orderly shift toward carbon mitigation.

The relevant framework is needed to make sure that a taxonomy classification, disclosure and verification are conducted objectively and transparently. Taxonomy should play a role in avoiding transition-washing9) by ensuring that economic and investment activities that facilitate the carbon neutrality transition are recognized. Companies should conduct the objective and transparent disclosure of their plans to meet net-zero targets set forth by the Paris Agreement and scientifically substantiate and verify the feasibility of the plans.

Features of financial intermediation designed for carbon neutrality

The transition to carbon neutrality is affected by long-term policies that reflect socio-economic preferences of stakeholders. As the development of transformative technologies, an enabler of the transition, is the product of scientific advancement, the transition process involves uncertainty. Accordingly, transition finance should take account of these characteristics.

Financial instruments aimed at supporting transition activities can be largely divided into ordinary bonds, sustainability-linked bonds and sustainability-linked loans.10) How such instruments meet the purpose of fund execution and align with an incentive mechanism related to carbon reduction verification can be enforced by a contract. For instance, if a power plant using carbon fuels issues sustainability-linked bonds to raise funds for carbon capture technologies, the bond yield could be linked to the effectiveness of such technologies. As the issuance yield is an effective tool to induce a shift in companies’ activities in that it affects the cost of capital. Furthermore, sustainability-linked loans offered in the form of relationship-based banking can be characterized by transition finance as they can encourage companies to move toward a low-carbon business structure by providing customized products and services.

On the other hand, shareholders have primarily adopted negative screening by excluding high-emitting businesses from investment portfolios. But this divestment strategy has been known for marginally affecting the change in corporate activities and effective carbon mitigation. If the price elasticity of demand is high, business types that are excluded from portfolios due to high carbon intensity would end up being integrated into other portfolios without considerable price changes and rarely have significant effects on the cost of capital.11) Substitute investors would show indistinctive preference to climate change and thus, incentives for corporate carbon neutrality become no longer valid. In the 2014 policy report,12) Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, states that shareholders should undertake a long-term engagement strategy designed to induce companies using or producing fossil fuels to systematically transition to decarbonization, which fulfills the purpose of increasing shareholder value. Korea’s National Pension Service also needs to consider adopting shareholder engagement to deal with climate issues based on the principles for responsible investment and guidelines on fiduciary duty.

Implications

Korea’s carbon neutrality policy is underpinned by the Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality. Article 58 of the Act (Financial Support and Revitalization) highlights the need for raising carbon neutrality funds, developing financial instruments, revitalizing private investment, stepping up disclosure of information regarding carbon neutrality, and facilitating transactions in the carbon market. Korea has founded the Presidential Commission on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth to establish and implement major policies and plans for carbon neutrality and green growth. To mobilize massive funds for the low carbon transition and effectively intermediate fund execution, the commission should handle finance as a critical part of the transition equation.

1) The first National Plan for Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth (government proposal) to achieve carbon neutrality and green growth by 2050

2) Kim, J.Y. & Jeon, E.K., 2021, Climate Change Transition Risks and Financial Stability, Bank of Korea Monthly Statistical Bulletin, Vol.75 No.12.

3) The analysis of Bank of Korea’s scenarios stems from climate change scenarios of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), under the assumption that execution and physical risks are minimized through an orderly transition.

4) The conversion sector refers to a sector consisting of electric power and calorie generation where fuel sources such as coal and gas are converted into electricity and thermal energy.

5) McKinsey & Company and Institute of International Finance, 2023, Financing the Net-Zero Transition: From Planning to Practice.

6) Klaaßen, L., Steffen, B., 2023, Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe, Nature Climate Change 13(1), 1-9.

7) OECD, 2022, OECD Guidance on Transition Finance: Ensuring Credibility of Corporate Climate Transition Plan.

8) G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, 2022, 2022 G20 Sustainable Finance Report.

9) If new investments made by high-emitting industries focus more on making the existing carbon-intensive process efficient than cutting carbon emissions, this could lead to negative consequences in the long run, such as GHG intensive lock-in.

10) Tandon, A., 2021, Transition finance: Investigating the state of play: A stocktake of emerging approaches and financial instruments, OECD Environment Working Papers No.179.

11) Berk J. B., van Binsbergen, J. H., 2021, The impact of impact investing, Research Papers 2981, Stanford University, Graduate School of Business.

12) Skancke, M., Dimson, E., Hoel, M., Kettis, M., Nystuen, G., Starks, L., 2014, Fossil-fuel investments in the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global: Addressing climate issues through exclusion and active ownership, A report by the Expert Group appointed by the Norwegian Ministry of Finance.