OPINION

2022 Dec/20

Korea’s Population Aging: Relevant Risks and Long-term Economic Growth

Dec. 20, 2022

PDF

- Summary

- Recently, a decline in fertility has deepened concerns over demographic structure. From a broader demographic perspective, aging baby boomers have caused equally serious problems. The baby boom generation represents a sizable share of the entire population and lower fertility rates have had a cumulative impact since the 2000s. Given these circumstances, even a dramatic increase in fertility hardly seems to change the expected course of demographic transition. Furthermore, as East Asian countries including China are seeing the advent of an aging society around the same time, it is hard to expect an influx of immigrants to buffer the effects of demographic aging. This suggests that population aging is a predetermined future, rather than a probabilistic projection. Some previous studies have found intensifying population aging responsible for sluggish economic growth. Considering its rapid aging trend, Korea would be far more influenced by an aging population, compared to other gradually aging OECD countries. As a response, the policy direction should be geared toward alleviating the adverse effects of rapid population aging and facilitating swift adaptation to the demographic shift.

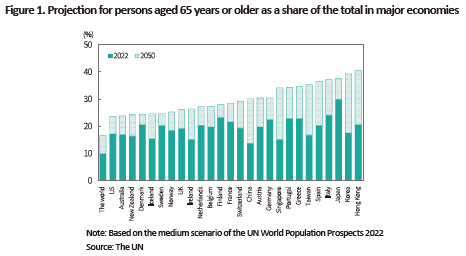

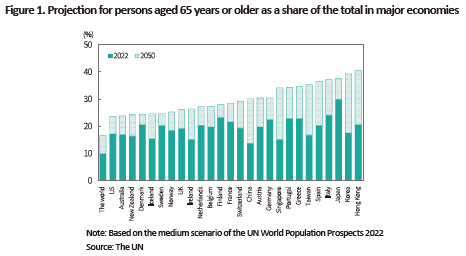

In Korea, the total fertility rate (the average number of children a woman would give birth to during her lifetime) stands at 0.79 births as of the third quarter of 2022, sparking concerns about falling fertility across society. Since the early 2000s, a wide range of low fertility policy measures have been introduced, starting with the establishment of the Framework Act on Low Birth Rate in an Aging Society. Despite such efforts, the total fertility rate that kept rising and falling from 2005 has suffered a severe drop since 2015, showing a continuous declining trend. Low fertility levels are projected to have a profound impact on various fronts such as education, national defense, industries and local administration, which would lead to a reduction in the school-age population, military personnel, working-age population, and local population extinction. From a broader demographic perspective, population aging has also emerged as a serious problem. According to the World Population Prospects released by the UN in June 2022, persons aged 65 years or older are projected to make up 39.4% of the entire Korean population by 2050, which is the largest share among the countries with a population of 1 million or over except for Hong Kong (Figure 1). If the difference in the ratios of population aged 65 or over for 2022 and 2050 is defined as the population aging rate, Korea would have the highest population aging rate of 21.9%p among major economies including Hong Kong.

Factors behind population aging

Why is Korea experiencing a steep rise in the elderly population? A decline in the fertility rate during the 2000s may partially contribute to such an increase but a more fundamental problem lies in the fact that the large baby boom cohorts have turned 65 since 2020. The baby boom generation refers to people who were born between 1955 and 1974. The generation totals approximately 16.6 million, representing 32% of the entire population as of 2020 since they are high in absolute number compared to other generations and rapid economic growth has raised their life expectancy significantly. By country, baby boomers make up 22.7% in Western Europe (born between 1946 and 1964), 10.3% in Japan (born between 1947 and 1953) and 22.4% in China (born between 1962 and 1975). This suggests that Korea’s relatively higher share of baby boomers has served as a major contributor to its fast-paced demographic aging. This analysis has been backed by Statistics Korea’s 2001 Population Projections which already predicted the share of persons aged 65 or older to reach 34.4% by 2050 before lower fertility rates materialized in the early 2000s.

Is there any potential option to delay population aging?

Would it be possible to alleviate the current aging trend by driving up fertility rates? Among advanced economies, Germany is expected to have a relatively larger share of the older population at 30.5% in 2050. If Korea would reach the same level as Germany in terms of population aging, it should have kept the number of births at 590,000—twice as many persons born in 2020—from 2000 to 2050. This indicates boosting fertility to a realistic level would be inadequate to turn the tide of the imminent aging trend. As illustrated in cases of other countries, fertility rates rarely rebound and the level of increase is limited and thus, a meaningful rebound needed to slow down population aging is hardly expected.

If so, could mass immigration fix this problem? Apart from practical challenges such as cultural differences, a language barrier and concerns over a tight labor market for local citizens, accepting immigrants to compensate for the lack of a working-age population seems to be a reasonable alternative. According to the UN World Population Prospects, the global population is projected to keep growing until 2086. What is overlooked in the discussions about immigration is that lower fertility rates and rapidly aging populations are not Korea-specific issues. A decline in fertility and an aging society are not affecting only high-income Asian countries including Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Japan. But such issues are also intensifying in China, Thailand and other medium-income countries. Particularly, if large economies such as China become enthusiastic about accepting immigrants, labor supply from foreign countries would only have a limited impact, despite the rising global population. If low-income countries in South East Asia—geographically and culturally close to Korea—gain greater income through rapid economic growth, their workers would be less motivated to move abroad. In addition, economic fluctuations and foreign exchange volatility may drive out migrant workers. As an alternative to immigration, it may be worth considering the supply of labor force through economic cooperation with North Korea. Given the uncertainty over inter-Korean relations, however, it would hardly be a reliable population policy option.

Effects of population aging on economic growth

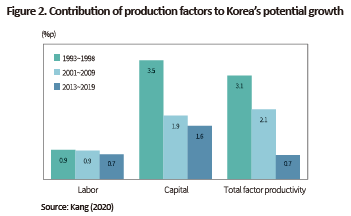

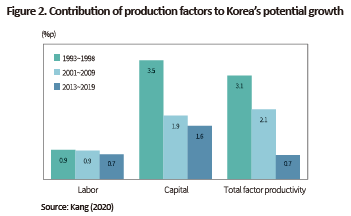

Considering a massive retirement rush of baby boomers, prolonged lower fertility and a slim chance of migrating population, it is fair to say that rapid population aging is a predetermined future, rather than a probabilistic prediction. To what extent is demographic aging likely to influence the long-term growth of the Korean economy? Previous studies on OECD members have found that an increase of 1%p in the population aged 65 years or over would translate into a decline of 0.2%p to 0.6%p in economic growth. When the figures are simply put into Korea’s population aging rate (the 21.9%p increase in the share of those aged 65 or older in 2050, compared to 2022), economic growth is projected to fall 4%p to 13%p in roughly 20 years. Notably, this projection has been derived based on the previous correlation between economic growth and aging populations in OECD members. Accordingly, the effects of population aging could be mitigated by progress in automation levels and higher economic participation rates of the elderly and women. Long-term growth prospects unveiled by major economic institutions, which have been reflected in the long-term outlook of pension funds or fiscal planning, have projected the growth rate between 2030 and 2040 to remain in the mid-1% range. But it is noteworthy that such projection has been under the assumption that inputs of labor and capital are curtailed while the total factor productivity maintains the current level, by and large. However, previous studies regarding population aging have pointed out the slowdown in productivity as a primary factor behind decreasing economic growth driven by population aging. On top of that, empirical studies on the relationship between labor productivity and working age have reported that workers aged 40 or older begin to show a downturn in productivity. As illustrated in Figure 2, Korea’s total factor productivity has suffered a continuous decline. Thus, the downside risks of major institutions’ long-term growth prospects would hardly remain modest. With gradually aging populations, advanced economies benefited from the integration of Eastern Europe and China into the global economy. In contrast, Korea experiencing a steep rise in its elderly population would be exposed to negative external conditions such as China’s simultaneous aging.

Suggestions for policy responses

How should we cope with a rapidly aging population? Policy responses should be geared toward alleviating the adverse effects of an aging society and providing support for swift adaptation to the demographic transition. Above all, it is imperative to enhance macroeconomic productivity through the advancement of the labor market in order to effectively use finite population resources. Another policy focus should be proactive restructuring for government finance or the national pension scheme, the sectors that are about to see a sudden rise in population aging-related spending. As a large number of recipients would be added, delayed or inadequate reform of government finance or pension funds could aggravate a burden for future generations, thereby making it difficult to implement any additional reform. Lastly, it is necessary to create a more elderly-friendly working environment to compensate for the shrinking working-age population. A higher labor force participation rate of the elderly could buffer the effects of population aging. As elderly-friendly jobs tend to be more female-friendly, the aging population’s greater participation in economic activities could also drive up women’s labor force participation rate.

References

Kang, H., 2020, Korea’s Long-term Economic Trend and Covid-19 Pandemic, KCMI Issue Paper 20-21.

Why is Korea experiencing a steep rise in the elderly population? A decline in the fertility rate during the 2000s may partially contribute to such an increase but a more fundamental problem lies in the fact that the large baby boom cohorts have turned 65 since 2020. The baby boom generation refers to people who were born between 1955 and 1974. The generation totals approximately 16.6 million, representing 32% of the entire population as of 2020 since they are high in absolute number compared to other generations and rapid economic growth has raised their life expectancy significantly. By country, baby boomers make up 22.7% in Western Europe (born between 1946 and 1964), 10.3% in Japan (born between 1947 and 1953) and 22.4% in China (born between 1962 and 1975). This suggests that Korea’s relatively higher share of baby boomers has served as a major contributor to its fast-paced demographic aging. This analysis has been backed by Statistics Korea’s 2001 Population Projections which already predicted the share of persons aged 65 or older to reach 34.4% by 2050 before lower fertility rates materialized in the early 2000s.

Is there any potential option to delay population aging?

Would it be possible to alleviate the current aging trend by driving up fertility rates? Among advanced economies, Germany is expected to have a relatively larger share of the older population at 30.5% in 2050. If Korea would reach the same level as Germany in terms of population aging, it should have kept the number of births at 590,000—twice as many persons born in 2020—from 2000 to 2050. This indicates boosting fertility to a realistic level would be inadequate to turn the tide of the imminent aging trend. As illustrated in cases of other countries, fertility rates rarely rebound and the level of increase is limited and thus, a meaningful rebound needed to slow down population aging is hardly expected.

If so, could mass immigration fix this problem? Apart from practical challenges such as cultural differences, a language barrier and concerns over a tight labor market for local citizens, accepting immigrants to compensate for the lack of a working-age population seems to be a reasonable alternative. According to the UN World Population Prospects, the global population is projected to keep growing until 2086. What is overlooked in the discussions about immigration is that lower fertility rates and rapidly aging populations are not Korea-specific issues. A decline in fertility and an aging society are not affecting only high-income Asian countries including Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Japan. But such issues are also intensifying in China, Thailand and other medium-income countries. Particularly, if large economies such as China become enthusiastic about accepting immigrants, labor supply from foreign countries would only have a limited impact, despite the rising global population. If low-income countries in South East Asia—geographically and culturally close to Korea—gain greater income through rapid economic growth, their workers would be less motivated to move abroad. In addition, economic fluctuations and foreign exchange volatility may drive out migrant workers. As an alternative to immigration, it may be worth considering the supply of labor force through economic cooperation with North Korea. Given the uncertainty over inter-Korean relations, however, it would hardly be a reliable population policy option.

Effects of population aging on economic growth

Considering a massive retirement rush of baby boomers, prolonged lower fertility and a slim chance of migrating population, it is fair to say that rapid population aging is a predetermined future, rather than a probabilistic prediction. To what extent is demographic aging likely to influence the long-term growth of the Korean economy? Previous studies on OECD members have found that an increase of 1%p in the population aged 65 years or over would translate into a decline of 0.2%p to 0.6%p in economic growth. When the figures are simply put into Korea’s population aging rate (the 21.9%p increase in the share of those aged 65 or older in 2050, compared to 2022), economic growth is projected to fall 4%p to 13%p in roughly 20 years. Notably, this projection has been derived based on the previous correlation between economic growth and aging populations in OECD members. Accordingly, the effects of population aging could be mitigated by progress in automation levels and higher economic participation rates of the elderly and women. Long-term growth prospects unveiled by major economic institutions, which have been reflected in the long-term outlook of pension funds or fiscal planning, have projected the growth rate between 2030 and 2040 to remain in the mid-1% range. But it is noteworthy that such projection has been under the assumption that inputs of labor and capital are curtailed while the total factor productivity maintains the current level, by and large. However, previous studies regarding population aging have pointed out the slowdown in productivity as a primary factor behind decreasing economic growth driven by population aging. On top of that, empirical studies on the relationship between labor productivity and working age have reported that workers aged 40 or older begin to show a downturn in productivity. As illustrated in Figure 2, Korea’s total factor productivity has suffered a continuous decline. Thus, the downside risks of major institutions’ long-term growth prospects would hardly remain modest. With gradually aging populations, advanced economies benefited from the integration of Eastern Europe and China into the global economy. In contrast, Korea experiencing a steep rise in its elderly population would be exposed to negative external conditions such as China’s simultaneous aging.

How should we cope with a rapidly aging population? Policy responses should be geared toward alleviating the adverse effects of an aging society and providing support for swift adaptation to the demographic transition. Above all, it is imperative to enhance macroeconomic productivity through the advancement of the labor market in order to effectively use finite population resources. Another policy focus should be proactive restructuring for government finance or the national pension scheme, the sectors that are about to see a sudden rise in population aging-related spending. As a large number of recipients would be added, delayed or inadequate reform of government finance or pension funds could aggravate a burden for future generations, thereby making it difficult to implement any additional reform. Lastly, it is necessary to create a more elderly-friendly working environment to compensate for the shrinking working-age population. A higher labor force participation rate of the elderly could buffer the effects of population aging. As elderly-friendly jobs tend to be more female-friendly, the aging population’s greater participation in economic activities could also drive up women’s labor force participation rate.

References

Kang, H., 2020, Korea’s Long-term Economic Trend and Covid-19 Pandemic, KCMI Issue Paper 20-21.